Summary

- Successfully implementing e-government measures in African nations is essential for achieving the African Union's Digital Transformation Strategy goal of establishing a digital single market in Africa by 2030.

- Nevertheless, many African nations continue to grapple with challenges in this area and risk not achieving the African Union's Digital Transformation Strategy goal of attaining a digital single market in Africa by 2030.

- In an effort to develop solutions, this paper evaluates the e-government measures of Africa's top performers - Mauritius, South Africa, Seychelles, and Tunisia - using the levels of e-government framework.

- An analysis of the e-government measures for these top performers reveals that a significant portion of their high performance can be attributed to "foundational" factors such as infrastructure, skills, and the legal and regulatory framework.

- It is recommended that African countries adopt a modular approach to developing innovative e-government strategies that meet the needs of citizens and business users in simple and cost-effective ways. This involves focusing efforts on their strongest "Level" of e-government and investing in customized solutions for specific functions that are considered a priority.

Executive Summary

Successful e-government implementation promises a range of well-recognized benefits, including improved public efficiency, more accessible services, greater citizen engagement and reduced administrative burden for private firms, which in turn leads to investment and job creation. Most African countries have embarked on a digitalization journey and started offering public services on online platforms. However, progress has been slow and uneven.

The dominant narrative on barriers to e-governance in Africa lists a daunting series of factors, most of which require significant time and funds to address: infrastructure, interoperability, the digital divide, skills and the regulatory framework. There is also corruption, long considered the true opponent of digitalization.

To learn from what is working well, this paper reviewed the experiences of Africa’s top performers in e-government, based on secondary research, interviews and the analysis of data from global e-governance indices. Four African countries score above the global average in the United Nations E-Government Development Index (EGDI): Mauritius, South Africa, Seychelles and Tunisia. Notably, Mauritius and Seychelles score extremely high on the human capital and telecommunications infrastructure dimensions of the index, as they boast a high volume of Internet users and, especially, mobile cellular subscriptions. For its part, South Africa leads the four countries on overall EGDI scoring but not in specific sub-indices within it, suggesting a balanced performance. Although Tunisia lags slightly behind the other three countries, it earns its place due to a robust institutional framework and high level of skills.

The authors deconstruct the data from the EGDI and two other global indices to consider specific functions and levels of e-government and identify sub-indicators related to the operational performance of e-government systems. The focus is intentionally narrow, on government-to-business and government-to-citizen transactions and the minimum conditions necessary to support these.

The paper’s operational focus is in contrast to much of the literature, which argues the merits of a whole-of-government approach and the need for long-term investments in foundational conditions (i.e., skills, infrastructure and the regulatory framework). While these elements are necessary, the authors argue that offering a better user experience for government administrative transactions is feasible and affordable in the short term, and can help build credibility and raise funds for more ambitious undertakings.

African policymakers that want to maximize the benefits from investments in e-government can follow the “Levels of e-government” decision-making framework presented in this paper. Levels include interfaces (front- and back-office), data security and exchange, and infrastructure. The simple definitions and examples demystify the technologies involved, and the modular structure is meant to allow governments to negotiate with tech suppliers for more options with less resources, focus on user experience and assess the costs and benefits of public-facing improvements.

At the end of the day, what determines African countries’ success in e-governance may be less related to whether public agencies can move together in lockstep, or how they choose to share data with each other, than simply whether they are asking the question, “What is it that citizen and business users need, and how can it be offered in a simple, low-cost way?”

Introduction

Africa’s digital transformation assets include a youthful, digitally savvy population, a relatively well-developed fintech sector and high-level commitments to trade integration.1,2,3 Recognizing the opportunity, the African Union’s recently published Digital Transformation Strategy includes the goal of a digital single market in Africa by 2030.4 A subset of the global digital transformation, the digitalization of government services, is widely accepted in both developed and developing countries as a pillar of economic growth.5

Successful e-government implementation promises a range of well-recognized benefits, including improved public efficiency, more accessible services, greater citizen engagement and reduced administrative burden for private firms, which in turn leads to investment and job creation. Most African countries have embarked on a digitalization journey and started offering public services on online platforms. However, progress has been slow and uneven.6

The dominant narrative on barriers to e-governance in Africa lists a daunting series of factors, most of which require significant time and funds to address: infrastructure, interoperability, the digital divide, skills and the regulatory framework.7 There is also corruption, long considered the true opponent of digitalization.8 Certainly, these factors are real – for example, intermittent power in rural regions makes it unrealistic to expect broadband Internet services to work even when they exist.

However, creative uses of technology can help address many of the challenges. Interoperability, for example, can be overcome by using web services. Mobile apps that work offline and other last-mile innovations can be used to support rural government agencies in providing digital services. In addition, recent funding trends along with new commitments indicate that the African Union’s Strategy for Digital Transformation in Africa will be receiving support on a major scale.9,10

This paper reviews the experiences of Africa’s top performers in e-government: Mauritius, South Africa, Seychelles and Tunisia. The research analyzed data from three global e-governance indices: the United Nations’ E-Government Development Index (EGDI), the World Bank'’s GovTech Maturity Index (GTMI) and Estonia’s National Cybersecurity Index (NCSI). We reviewed secondary literature to develop four case studies and conducted key informant interviews with experts in the field.

To learn from what is working well and pinpoint where problems still exist, we deconstructed data from each index, aiming to isolate performance-related information according to specific functions and levels of e-government. Most indices cover “foundational” conditions (e.g., skills, the existence of laws) as well as performance variables (e.g., how many services are currently online). The discussion of foundational issues is limited to the case studies, while a comparative analysis aims to address the practical “here-and-now” necessities of e-government. From the indices, the authors identify sub-indicators that relate to the operational performance of e-government. The focus is intentionally narrow, on government-to-business and government-to-citizen transactions and the minimum conditions necessary to support these.

Methodology

Governments are complex, technology is complex, and e-government is exponentially complex. For this reason, in an intentional effort to “demystify” the technical aspects of e-government, this article uses a “Levels of e-government” framework that clearly defines all the necessary operational functions enabling the delivery of online services. Services from one agency to another are known as government-to-government (G2G), while services delivered to outside constituents are government-to-citizen (G2C) or government-to-business (G2B). This article focuses primarily on services to outside constituents or customers (G2C and G2B, respectively).

Today, the globally accepted norm is to seek to integrate government agencies so that they can communicate with one another, i.e., horizontal integration.11 The emphasis on integration flows from the “whole of government approach” introduced in the early 2000s in Anglo-Saxon countries like the United Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand. The idea is “to offer citizens seamless rather than fragmented access to services.”12 In practice, one would expect this approach to prioritize the delivery of public sector services in ways that ensure that business or citizen needs come first instead of a line ministry mandate. For example, if a person’s goal is to start a small company, then he/she can get everything done within one customer journey (incorporate, register as a taxpayer, activity licensing, etc.). Currently, however, despite significant investments in agency-to-agency integration, this result has been elusive.13

Today’s technological solutions (such as web services and especially microservices) mean that it is not always necessary to have achieved full inter-agency coordination in the back-office in order to provide a seamless experience in the front-office. Why should the Ministry of Industry and the Ministry of Environment in Tunisia need to walk in lockstep, as long as businesses seeking approvals can easily submit their documentation to each (at the click of one button) and know the status of their application?

In the Levels of e-government framework, functions are treated as modules, where each one stands alone, but all can work together. No assumptions are made about what needs to happen first. In a context where public investment decisions may be made by policymakers with varying levels of expertise, the framework is specifically designed to support technical and operational decision-making by non-experts. It can help government leaders address precisely those questions that technology service providers will have strong opinions about but should not make alone (e.g., Make or buy a system? Upgrade legacy systems or start from scratch? Prioritize horizontal or vertical integration? Align data exchange and security protocols with which standards?) Used successfully, the framework allows government technology teams to prioritize urgent public-facing challenges and solve them efficiently and cost-effectively, without giving up ownership of the long-term vision for the overall system.

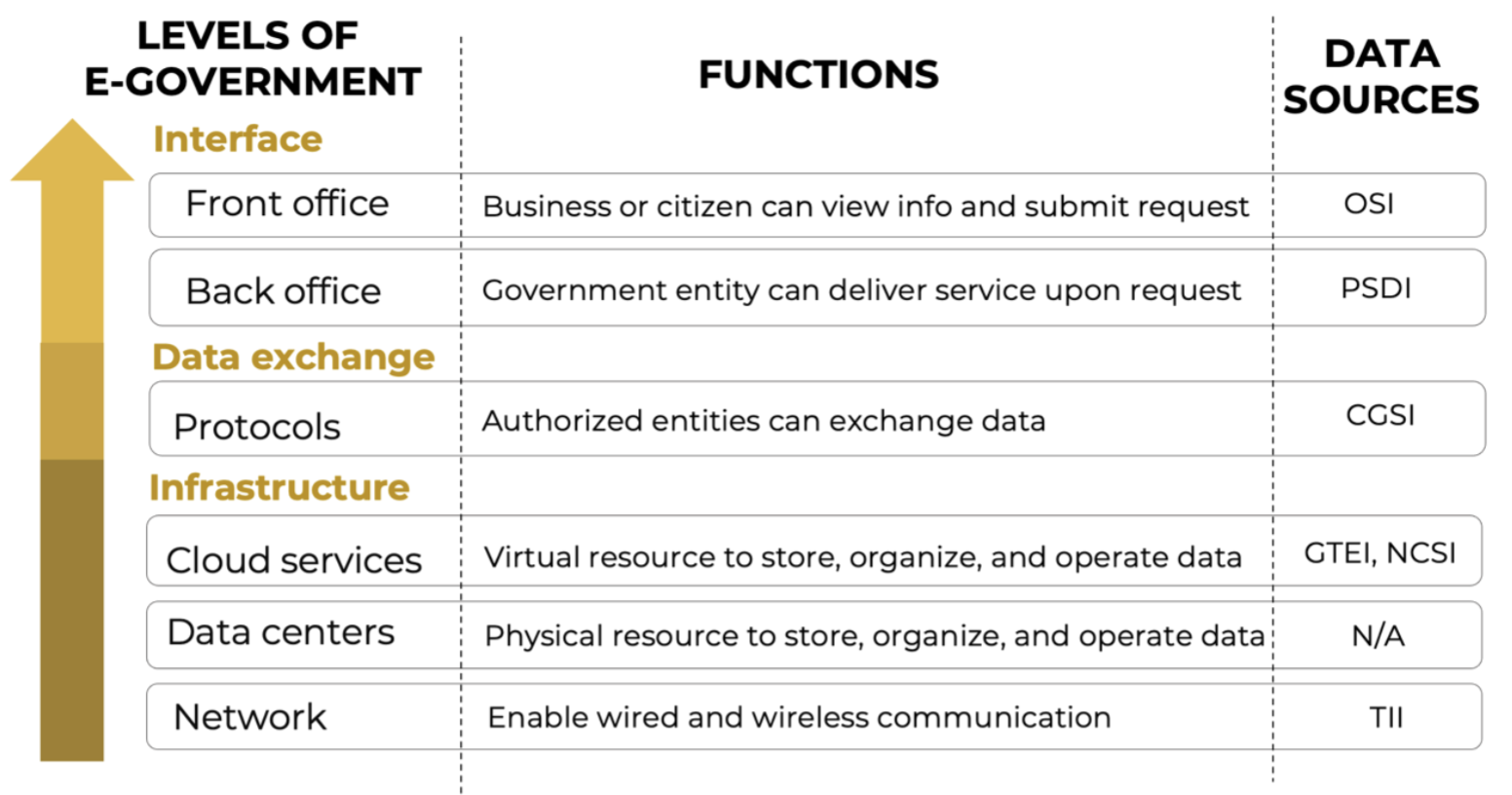

Figure 1 shows the three e-government levels: interface, data exchange and infrastructure. For each, there are one or more functions, shown in the left-hand column. Functions are briefly defined in the middle column and with additional detail in the bullet points below. In e-government, functions are enabled by technical solutions such as software, hardware and/or infrastructure. Finally, the right-hand column titled “Data sources” identifies the sources of performance indicators.

- Front-office: software solutions enabling users to find and submit information to relevant government agencies to access public services.

- Back-office: software solutions enabling a government administrator to review, approve or reject administrative requests and applications to deliver public services to business or citizen users.

- Protocols: rules governing secure government networks that enable authorized entities to exchange data.

- Cloud services: virtual resources to store, organize and operate data.

- Data centers: physical resources to store, organize and operate data.

- Network: infrastructure, including broadband and mobile, to enable wired and wireless communication.

Figure 1.

Levels of e-government framework

To provide an apples-to-apples comparison across the case studies, we reviewed the content of the major e-government indices and then selected sub-indicators that relate directly to each of the six levels of the framework above. The authors then combined indicators from three different indices into a composite index, composed of 6 sub-indices. The sub-indices correspond directly to the functions shown in the Levels of e-government framework. The global indices from which the six sub-indices and their individual indicators were drawn are:

- The United Nations’ E-Government Development Index (EGDI), is a composite index that measures the e-government development of countries based on three dimensions: (i) the availability of online services, (ii) the level of telecommunication infrastructure and (iii) the capacity of human capital. The EGDI ranks countries based on their score on these three dimensions, and it provides a benchmark for monitoring e-government development over time. EGDI scores range from 0 to 1, with higher scores indicating greater levels of e-government development. Our decision-making framework presented below uses the following sub-indices from EGDI: the Online Services Index (OSI) and the Telecommunication Infrastructure Index (TII).

- The World Bank’s GovTech Maturity Index (GTMI), is a composite index that measures the maturity of a country’s government technology (GovTech) ecosystem. It assesses the maturity of four dimensions of GovTech: (i) institutional and regulatory environment, (ii) digital infrastructure, (iii) digital services and (iv) capacity building. The GovTech Maturity Index helps countries identify areas of improvement in their GovTech ecosystems and provides a roadmap for developing and implementing effective GovTech strategies. GTMI scores range from 0 to 1, with higher scores indicating greater maturity of a country’s GovTech ecosystem. World Bank staff emphasize that it is not meant to be comparative as much as developmental. Our decision-making framework uses the following sub-indices from GTMI: the Public Service Delivery Index (PSDI), the Core Government Services Index (CGSI), and the GovTech Enablers Index (GTEI).

- Estonia’s National Cybersecurity Index (NCSI) measures the level of cybersecurity in a country. It assesses the cybersecurity capabilities of a country based on five dimensions: (i) legal and regulatory framework, (ii) technical measures, (iii) organizational measures, (iv) capacity building and (v) cooperation and coordination. The NCSI helps countries identify areas of weakness in their cybersecurity strategies and provides a benchmark for monitoring progress in improving cybersecurity capabilities. NCSI scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating greater cybersecurity capabilities. Our decision-making framework uses the following indicators from NCSI: protection of digital services, and protection of essential services.

Annex 1 details the individual indicators drawn from these indices and the classification of each by function in the Levels of e-government framework.

Once we had selected the appropriate indicators from the global indices and organized the data from these for all four countries, we proceeded to build a model which would be able to show each country’s score for each level of the index. To make data from different indices comparable and eliminate the influence of varying scales and magnitudes of data, we employed the min-max scaling method. This normalization technique involved scaling the data to a common range. By doing so, we ensured that the values across different indices were on a similar scale, allowing for meaningful comparisons and analysis. All sub-indices were equally weighted to avoid giving disproportionate importance to any specific area. By assigning equal weights, a balanced representation of each sub-index in the overall index calculation was ensured. This approach prevented any single component from dominating the final results.

In the narrative below, we first provide a simple side-by-side comparison of the case study countries’ performance for the three global e-government indices used and briefly describe the salient features of each country’s performance on the EGDI. Then, we review qualitative information about each country’s e-government achievements, organized along the levels of the e-government framework. Last, we calculate the levels of e-government index, draw conclusions from the analysis, and offer recommendations for how African leaders can take a systematic approach to exploit the full potential of the e-government opportunity.

Measures of E-governance

Only four African countries come above the global average in the United Nations E-Government Development Index (EGDI): Mauritius, South Africa, Seychelles and Tunisia. Table 1 shows the four case study countries’ raw scores and their comparative rank for a few of the most well-known e-government indices, namely: the United Nations’ EGDI, the World Bank’s GovTech Maturity Index (GTMI) and the Estonian e-Governance Academy’s National Cyber Security Index (NCSI).

The United Nations EGDI is a composite made of three categories: the Human Capital Index (HII), the Telecommunications Infrastructure Index (TII) and the Online Service Index (OSI). The index is based on an annual survey and is meant to serve as a benchmarking and development tool for countries to learn from each other. The index considers foundational elements, like digital skills and civic participation, as well as operational elements, such as the availability of services. It is to be noted that while we acknowledge these foundational elements to be critical, they are not included in the levels of the e-government framework, which – as explained above–- is meant to inform technical and operational decisions. Investments in digital skills or civic participation, on the other hand, are considered cross-cutting, and need not be thought of as “either-or” in this context.

Table 1.

Comparative table of case study scores on EGDI and other indices

| Index – score | South Africa | Mauritius | Seychelles | Tunisia |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EGDI 2022 score (0 to 1) | 0.74 | 0.72 | 0.68 | 0.65 |

| Rank among African countries | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| GTMI 2022 score (0 to 1) | 0.56 | 0.86 | 0.45 | 0.69 |

| Rank among African countries | 13 | 1 | 21 | 7 |

| NCSI 2022 score (0 to 100) | 36 | 44 | 10 | 53 |

| Rank among African countries | 10 | 8 | 32 | 6 |

Notably, Mauritius and Seychelles score extremely high on the human capital and telecommunications infrastructure dimensions of the index, as they boast a high volume of Internet users and especially mobile cellular subscriptions. Seychelles performs particularly well in both telecommunications and human capital, with a relatively lower scoring on service provision, whereas Mauritius has a more balanced performance across these dimensions. For its part, South Africa leads amid the four countries on overall EGDI scoring but not in specific sub-indices within it, suggesting a balanced performance. South Africa’s strengths as displayed by its EGDI scoring include a robust institutional framework and content provision in terms of online service provision and in line with Seychelles and Mauritius, a high volume of Internet users and mobile cellular subscriptions as well as educated, digitally savvy populations. Interestingly, Tunisia lags slightly behind the other three countries and stands out for a robust institutional framework driving up its online service delivery scoring, while sharing with the rest, once again, plenty of Internet users, mobile and fixed broadband subscriptions and robust education and digital literacy indicators.

Africa’s Top Performers

While overall EGDI scores and critical enabling factors such as the legal and regulatory environment are acknowledged, the narrative below analyzes each country’s performance with a focus on technical and operational factors, by relating their achievements to the “levels of e-government” framework presented above.

South Africa

South Africa’s enabling factors include a strong regulatory framework (see Figure 2), a critical mass of private sector firms, deep and diversified financial and capital markets, competence in research and development, several internationally recognized universities and wide coverage of mobile broadband.”14

Under the aegis of the DCDT (Department of Communications and Digital Technologies), South Africa’s front-office delivers a robust set of services:

- Its digital identification (ID) system boasts comprehensive citizen coverage and strong existing public-sector service infrastructure. ID authentication and renewal is centralized in the e-Home Affairs site.sup>15 The system enables not only public actors but also banks and the private sector to authenticate credentials against a central database.

- A functional e-government procurement system16 centralizes access to tender information from all government agencies and contains a central supplier database17 managed by the Treasury.

- The South African e-service portal, a one-stop shop for public services to citizens and transactions with the Government to be undertaken entirely online, is maintained by the State Information Technology Agency (SITA). Available services include e-permits (environmental permits), e-metric, e-registration (to sit public examinations), e-campaigns and e-events.

- A number of services are still in development, including export/import permits, fleet management, e-complaints and registering as a job seeker.18

There are challenges, however. South Africa has a profusion of institutions with overlapping mandates.19 In addition, other key hurdles impact front-office service provision:

- There is no strong push for mainstreaming open Application Programming Interfaces (APIs).20

- Counterfeiting and spoofing of IDs remains recurrent and further authentication infrastructure is required.21

- The cybersecurity policy framework suffers from implementation shortcomings.

In the back-office, national government functions are overwhelmingly digitalized and enabled by SITA, which remains responsible for their maintenance.22 The back-office technical and informational support to the front-office is a key strength for South Africa and sets the country apart from the other three countries. Yet, the transversal integration of e-government functions remains incomplete. At the provincial levels, there is substantial divergence among central government functions as well as among provinces, with Gauteng and Western Cape as the top performers.23

In terms of protocols, interoperability remains a crucial challenge.24 For example, the national digital ID system, as robust as it might be, suffers from insufficient coordination as national and local government levels do not always talk to each other (or not enough) and as a result, not all ID authentication processes are end-to-end digitized. A constructive step in this regard is the development of the Minimum Interoperability Standards (MIOS), which enable a minimum level of interoperability within and between ICT systems employed not just by the Government, but also by industry, citizens and the international community in improved policymaking.25

Figure 2.

E-government strategy, policy & legislative framework in South Africa

Under the overarching framework of the National Development Plan 2030, South Africa’s key e-government policy is the National e-government Strategy and Roadmap, developed in 2017 with three strategic thrusts: e- services, e-governance and a digitally-enabled society. Other policy milestones include the National broadband policy of 2013, the National Integrated ICT Policy White Paper of 2016, and the National e-Strategy, covering a wider scope, i.e., digital and knowledge economy.

The legislative framework may be the most exhaustive among the countries analyzed and includes:

- Legislation related to public service delivery, like the Public Service Act of 1994, or the Skills Development Act of 1998 focused on digital skills of public officials.

- Legislation focused on digital services (both public and private sector), like the State Information Technology Agency Act of 1998 that created SITA and amended in 2020, or the Electronic Communications and Transactions Act of 2005.

- Supporting legislation like the Intellectual Property from Publicly Funded Research Act (IPR Act) of 2008 or the Protection of Personal Information Act (POPI Act) of 2013, equivalent to Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

The National e-Government Strategy and Roadmap,26 which drives the country’s e-government policy agenda, recognizes the importance of cloud services. Two regions, Gauteng and Western Cape, are advanced in storing data using cloud solutions. Recent activity includes a market analysis to explore the regional cloud ecosystem conducted for the Community of Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) by the African Development Bank (AfDB) through a special multi-donor fund.27 In terms of data centers, DCDT is reported to be building a High-Performance Computing and Data Processing Center which will facilitate the storage of data captured by the government from users and transactions into its secure server. Currently, evidence points to the direction of agency-specific server systems that talk to each other but are not entirely integrated from end to end.

In terms of network, South Africa boasts the continent’s most extensive backbone network infrastructure with almost universal mobile broadband coverage.28 This key strength of South Africa is supported by government institutions with well-defined remits and effective policymaking, notably the Independent Communications Authority of South Africa (ICASA),29 and South Africa Connect (SA Connect),30 both enabling the country’s impressive broadband coverage and closing connectivity gaps in rural areas and underserved municipalities. The focus on universal access to services and connectivity has seen the creation of the Universal Service and Access Agency of South Africa (USAASA),31 which manages the Universal Service and Access Fund (USAF), a facility to fund projects and programs promoting universal services and access to ICT. Concerning hard infrastructure, there are five submarine cables connecting the country to global networks, and via private investment, South Africa has successfully transitioned to an open competitive regime in its international connectivity. The country has had a National Broadband Policy since 2013, with an update to this policy pending.

In terms of implementation challenges, fiscal consolidation requirements have resulted in funding bottlenecks that have occasionally impacted the government’s ability to deliver on its e-government targets and commitments. Some observers point to an insufficient reliance on private sector investment, which is mobilized in a rather minimal way, to provide for more efficient, technical and cost-effective implementation, particularly in rolling out some e-government platforms.32

Mauritius

Mauritius, with an EGDI score of 75 and a GovTech Maturity Category A classification, offers an exemplary case study with valuable lessons for smaller economies, particularly Small Island Developing States (SIDS) unable to seize economies of scale and facing accessibility challenges due to geographical isolation. E-government efforts in Mauritius have benefitted from the élan of successive administrations determined to position the country as an ICT bridge between India and Africa and between the continent’s English and French speaking nations. Enabling factors include ease of doing business, socio-political stability, an educated workforce, the financial, fintech and ICT industries, as well as its Business Process Outsourcing (BPO) industry as a key rising sector amid a diversified and dynamic economy. Mauritius is also the first African country with a specific Artificial Intelligence (AI) Strategy as well as an AI Council.33

Figure 3.

E-government strategy, policy & legislative framework in Mauritius

Under the overarching framework of Mauritius Vision 2030, Mauritius stands out for its twin landmark strategies for e-government:

- The Public Sector Business Transformation Strategy (PSBTS), to promote optimization of public service delivery with technological improvement as a key tenet.

- The Digital Government Transformation Strategy (DGTS) 2018-2022, sets the country apart in terms of a purposefully specific e-government strategy, with clear mandates, anchored on a comprehensive feedback-gathering survey involving both intra- and extra-Government stakeholders and with specific policy proposals.

Mauritius also has a comprehensive legislative framework with acts targeting more specific fields than the national legislation in other countries, such as:

- National Computer Board Act (1988)

- Electronic Transaction Act (2000)

- Information and Communication Technologies Act (2001)

- Computer Misuse and Cybercrime Act (2003)

- Data Protection Act (2017)

This is complemented by a solid battery of targeted and highly-technical policies and strategies, like:

- National Broadband Policy 2012-2020

- National ICT Strategic Plan (NICTSP)

- National Cybersecurity and Cybercrime Strategies

- National Cyber Security Strategy (2014 - 2019)

- National eWaste Policy, Strategy and Action (2015)

- National Open Data Policy & Open Data Portal

- Digital Mauritius 2030 Strategic Plan

In terms of the front-office, service delivery according to user needs is a key government priority as per the Digital Government Transformation Strategy (DGTS) 2018-2022. DGTS and the Digital Mauritius 2030 Strategic Plan (with its focus on transforming Mauritius into a full digital economy), were developed after extensive stakeholder consultations. Arguably, few countries have founded their e-government policy frameworks on such a comprehensive feedback-gathering exercise, including the point of view of end users themselves.

Available digital public services include e-justice, e-procurement and e-work permit, to name a few. There is also an e-payment service that enables online payment for a number of transactions, such as police fees, land-leasing fees, driving licenses, business incorporation or parking fines. However, it must be noted that each digital service available to end users is managed by the corresponding public institution in a rather siloed way, and the InfoHighway (discussed below) is not universally used.

In the back-office, the Public Sector Business Transformation Strategy (PSBTS) aims to optimize government processes. In addition, there is a fit-for-purpose governance structure to implement all the government’s digital projects, composed of three committees: a minister-led committee for national scope, a project steering committee at the level of the user ministry or department and a project monitoring committee.

Regarding protocols, intra-government data sharing is enshrined in PSBTS, but data silos are identified as a relevant constraint. What makes Mauritius stand out, as the only country in Africa with fully operational data exchange, is the flagship initiative InfoHighway,34 a unique platform developed by the Ministry of Information Technology, Communication and Innovation (MITCI). InfoHighway enables seamless, full data-sharing between government agencies, enhancing transaction efficiency at the front-office level and being available in real time and 24/7. The process is simple: A public agency named publisher shares the data with another one requesting the data called subscriber, but for that, they both have to first file an application form to the MICTI, who approves the application and enables the sharing of data.

In terms of cloud services, data storage is to an important extent centralized under a “Government Cloud (GOC)”35 hosted by the National Computer Board (NCB). This Government Cloud hosts both physical servers and cloud environments as it manages the web server hosting all government websites and technically supporting them. Specifically, GOC provides the information infrastructure that underpins the help desk set up at the Government Online Center to support the delivery of 66 e-services from various Ministries and Departments. GOC also provides Internet access and other supporting functions to the public sector, notably a Government Email Services (GES) system that has set up email systems for the majority of government employees.

The centralization of data centers under one single infrastructure point sets Mauritius (along with Tunisia) apart from the disparate institutional setting for data centers found in its peers (notably Seychelles, with South Africa somewhere in the middle). The Mauritius GOC serves as the main data center to store and manage government information securely. Likewise, Mauritius stands out in the institutionalization of a Data Protection Office with its remit focused on regulating and enforcing privacy rights. The Mauritian Government has also developed a National Open Data Policy36 and an Open Data Portal.37 The African Union, as part of the African Internet Exchange System (AXIS) project, has built up Internet Exchange Points (IXPs) and provided technical assistance on planning, regulation, cost savings, etc. In this regard, the Mauritius National Internet Exchange Point (NIXP) enables an exchange of local Internet traffic between Internet service providers, working as an informal partnership between NCB, MICT and private-sector Internet service providers.

Mauritius benefits from a network with unique deep-sea cable connectivity, with two existing cables (Lower Indian Ocean Network (LION)/ MElTing pot Indianoceanic Submarine System (METISS)/ South Africa Far East (SAFE) / Mauritius–Rodrigues Submarine (MARS) and a third in the making as part of the “Indian Ocean Xchange Cable System.” Mauritius is doing particularly well in terms of connectivity and access, with 151% mobile penetration rates and 87% broadband penetration rates in 2022.38 Its vibrant and robust ICT sector delivers widespread access and connectivity rates, attributed to the liberalization of the telecommunication industry and intense competition.

To facilitate implementation, Mauritius has developed a governance structure of three committees at different levels (ministerial, project-steering and project-monitoring) to oversee its e-government work, which has proved effective in avoiding troubles such as those faced by other countries (e.g., competing priorities and overlapping mandates).

Seychelles

With an EGDI ranking of 85, Seychelles, like Mauritius, offers valuable lessons to smaller developing nations and Small Island Developing States (SIDS). Its policy and regulatory frameworks contain the key building blocks (i.e., data protection and access to information as per box below).39 As mentioned earlier in the discussion of Seychelles’ performance on the EGDI, there is a high level of digital literacy. Seychelles’ policy and regulatory framework is simple but well-designed, and the country has a strong telecommunications infrastructure. Digital adoption is consistent across governments and there are strong in-house technical capacities within the key institution, namely the Department of Information and Communications Technology (DICT), supported by a massive amount of fully-digitized government data.40

Figure 4.

E-government strategy, policy & legislative framework in Seychelles

Under the overarching framework of Vision 2033, Seychelles’ legislative and policy framework includes fewer initiatives with a broader and less technically-specific scope compared to its peers. The key e-government framework is the Institutional Strategic Plan of DICT (Department of Information and Communication Technologies), which lists policy actions in arenas like expanded access and affordability or better intra-Government connection, displaying this inward tilt and insufficient service-delivery awareness to the outside user of Government services that features this country. Other relevant policies include:

- The Government’s Results-based Management Policy (RBM) of 2013, focused on enhancing the efficiency of public spending more generally.

- The National ICT Policy (NICTP) developed by the National ICT Consultative Committee, with Government as one of the 5 policy focus areas

- The Central Bank of Seychelles FinTech Strategy, under development with World Bank support

- Plans and policies regulating radio frequencies, communications antennae, or fixed broadband wireless access

In terms of legislation, with a clear need for deepening and updating, it is worth mentioning:

- Broadcasting and Telecommunication Act of 2000

- Data Protection Act of 2003

- Access to Information Act of 2018

However, one comment that has been repeated by multiple development partners and observers is the need for prioritization so that more resources are not spread too thinly among a large number of projects.41 The digitization process has been less organized than in Mauritius, leading to a somewhat ad hoc, action-oriented approach to e-government that clearly tilts to supporting intra-government functions rather than outward-looking service delivery to end citizen or business users of public services.

In the front-office, Seychelles’ service provision lags slightly behind that of South Africa, Mauritius or Tunisia. Digitization for many administrative procedures is not full-fledged: The process starts online but, at one point or another, it requires some form of physical trips or paper forms. Priority seems to lie in serving internal government demands rather than offering citizens and businesses high-quality online services. Illustrative national initiatives include:

- SeyID is a fully end-to-end digital ID system with authentication and a legal guarantee. The system enjoys ample use and strong public support and is available to visitors.

- SeyGo Connect is the centralized government portal for digital public services, structured by topic: business and industry, culture, education, employment, etc. Like the Mauritius portal, it redirects to the relevant agency’s website rather than allowing for the transaction to be fully undertaken at the portal itself. There is also a “download form” functionality that allows access to many forms organized by four themes.43

- E-Services Gateway includes business licensing, vehicle licensing, import/export permits, filing tax returns, digital signature verification, etc. The Gateway may overlap with SeyGo Connect as it gathers multiple procedures under one single window. It also includes a tender board sorted by latest publication date. In some instances, the portal redirects the user to each institution’s website to deliver the service or perform the transaction, instead of enabling the whole procedure in the portal itself. The scope of their government service bus is reportedly shared (as opposed to siloed) but this is difficult to verify when visiting the site.

An interesting milestone for Seychelles has been the development of a facial biometric solution for border control allowing for contactless patrolling in the context of the COVID pandemic.44 This is a uniquely pioneering initiative in Africa, leveraging AI and machine learning technologies. Specifically, a modular architecture provides border control through the Visitor Management Platform (VMP). This is a holistic solution that encompasses facial recognition, temperature checks, uploading of travel info (passports, etc.), submission and verification of required health documentation and contactless passenger screening through a biometric corridor.

In terms of the back-office, Seychelles may be an exception. Whereas, in countries like South Africa, there is a specific agency (like SITA) to enable digitalization across government, in Seychelles, each ministry or agency has advanced its digitalization agenda in an inward-looking manner. A key challenge resulting from this is insufficient investment in security.45 However, it is to be noted that Seychelles is a pioneer in tying government digitalization to public service delivery and public sector efficiency, as it has put in place a Results-based Management Policy (RBM)46 since 2013, geared to increase public expenditure efficiency via a results-based management approach.

Regarding protocols, the multiple digital initiatives of the government have shown little evidence of talking to each other and sharing data. Unlike in Mauritius or South Africa, services are visible on multiple portals, but there is no functionality to connect them, and no entity tasked with ensuring cross-agency interoperability or security. Admittedly, the Seychellois government has an e-Services Gateway to provide a secure single-entry point to any transaction with the government, including a list of available services. Beyond that, however, there is a lack of coordination or common standards across agencies.

In terms of cloud services, reportedly there is a massive amount of government data that is stored using cloud solutions thanks to widespread and effective government-wide digital adoption, but data storage functionalities are isolated and disparate. As one example, SeyID embeds a cloud signature solution that enables users to have their ID stored in an app and thereby digitally sign legally valid documents and undertake other transactions, but it is not wholly connected to the rest of the system or to every public service transaction. Admittedly, the e-Services Gateway takes and stores data from individual and business e-IDs to verify their credentials and activate an account that allows the user to undertake a number of transactions. On the converse side of the mirror, SeyGo Connect centralizes government information in terms of service availability and delivery and stores it, but there is no evidence that both the e-Services Gateway and SeyGo Connect, with their respective remits, are woven together in terms of data sharing and storage to provide a seamless bidirectional flow of information as a transaction is undertaken.

Regarding data centers, as stated above, it appears that each ministry or agency either houses its own data or outsources it to a cloud solution provider. In this way, the rather siloed way of working of each government agency and the lack of digital integration across the public sector mean that each agency has its own secure server system and there is no government-wide centralized hosting.

In terms of network, Seychelles stands out for being Africa’s leader in the Telecommunications Infrastructure Index (TII) that is one of the three subcomponents of the EGDI, chiefly thanks to its top-notch Internet connectivity and volume of mobile-cellular subscriptions. It also has a solid hard infrastructure, reinforced by donor support. The European Investment Bank co-financed with AfDB the Seychelles East Africa Submarine cable project, finished in 2013, which was based on a Public Private Partnership (PPP) establishing the first submarine fiber optic cable for international connections of Seychelles to the African continent.

Regarding implementation challenges, the lack of a service-oriented and user-centric perspective has resulted in low usability as the system is devised to support internal government functions rather than to meet user or citizen needs.47 In addition, as Seychelles started to roll out its multiple programs and policies, it became abundantly clear that there was an excess of simultaneous projects with too few resources, as illustrated by a ratio of one person per every two digital projects. Development partners and observers have recommended that Seychelles would do well to scale back its ambition, define priorities and focus on a handful of high-value projects.48

Tunisia

Tunisia boasts a highly educated and digitally savvy population, and this is one factor contributing to its high EGDI score. The country has also, in the past eight years, passed a number of laws (cited in Figure 5 below) making it possible for the government to provide digital services. However, Tunisia is a clear case of an economy where the administrative burden is visibly hampering growth and the country’s ability to reach full employment.49 Despite significant advances during COVID, supported by joint efforts delivered by the private and public sector50 (the ability to pay taxes online, the vaccine platform, e-payment and e-signature), the government has struggled to adopt or implement a clear digitization strategy.

In the front-office, there are a plethora of information platforms, but most are not transactional due to unautomated back-office processing. The platform (E-t@srih) connected to the portal of the Ministry of Finance (E-Jebaya) for the reporting and payment of corporate taxes is one of the most mature, although the rate at which firms switch to paying taxes online has been slower than expected and does not meet the government's objectives. The status of other systems varies widely:

- The customs system, Tunisia Trade Net (TTN), which in its day was visionary (the first global single window concept having been articulated over fifteen years ago) is today suffering from reduced resources, with the digital platform as once envisioned only partially operational. Therefore, traders must do much of their work to clear merchandise through customs on paper. Citizens living abroad also suffer customs delays when bringing personal effects into the country.

- A bright spot is the Registre National des Entreprises (RNE), a semi-autonomous version of what in a French legal system is typically known as the Commercial Registry. This entity allows businesses to search and reserve names and provides them with documents needed to conduct official business in Tunisia, offering digital services via a sleek new website and forthcoming mobile app.

- As part of the commitment for transparency and the fight against corruption and in light of the many scandals involving high officials that have occurred in the process of awarding public contracts, the E-procurement platform was developed with funding from the Korea International Cooperation Agency (KOICA). Since 2018, electronic procurement has been mandatory for all entities.

- For a number of years, Tunisia had an aspiration to build a government-wide service portal that would contain everything businesses and citizens needed. United States donors had originally considered funding the business portal but it was then dropped. Currently the African Development Bank has allocated some funding to a citizen portal with similar aspirations, though progress has been extremely slow.

Figure 5.

E-government strategy, policy & legislative framework in Tunisia

Under the overarching framework of the Plan National Stratégique Tunisie Digitale 2020, Tunisia is focused on adopting digital transformation as an economic development tool. Due to insufficient progress, the project has been extended to 2025. Referred to from this point on as the Digital Tunisia Plan, it covers four objectives:

- Infrastructure: generalizing access to broadband Internet and developing high-speed Internet.

- e-Gov: transforming administrative services through the use and adoption of digital technology to enhance efficiency and transparency of operations for citizens and businesses.

- e-Business: aimed at transforming businesses through digital technology to enhance competitiveness, productivity, making innovation a driving force that supports all sectors.

- Smart Tunisia: placing Tunisia among the top three countries in offshoring of IT services.

In terms of legislation, Tunisia has adopted laws regulating electronic exchange and e-commerce in 2000, e-signature in 2001, cybersecurity in 2004, the protection of personal data in 2007; and has created specialized agencies to supervise and operationalize related activities: electronic verification via Agence Nationale de Certification Electronique (ANCE), data protection via Instance Nationale de Protection des Données à Caractère Personnel (INPDP) and cybersecurity via Agence Nationale de Sécurité Informatique (ANSI). Nonetheless, there is a need to update these laws and the mandate of the accompanying agencies (and perhaps merge them as currently they do not always agree). A recent accomplishment was the inclusion in the 2022 Finance Law of a provision allowing the payment of administrative services through any reliable electronic payment method.

In the back-office, the most developed internal IT team51 sits in the Ministry of Finance, and of course the Ministry of Interior operates its own systems with its own stricter security standards. Beyond this, the majority of agencies are left to negotiate with development partners on their own, resulting in an inefficient use of funding allocated to multiple competing portals (witness, for example, the Ministry of Industry and the Agency for Renewable Energy which in principle reports to the Ministry, each working separately with different partners on portals that are not designed to communicate, and yet are slated to contain some of the same services).

In terms of protocols, there are plans to establish a major software platform to ensure interoperability and data exchange. There is currently a debate within the government about whether to invest in an intranet called Réseau National Intégré de l’Administration (RNIA) or to use the Estonian data highway service (X-Road).

In terms of cloud services, the government aspires to have a cloud, but does not yet. Data related to Tunisian citizens is required to be hosted on Tunisian soil, so private international options are not relevant. The Tunisian Ministry of Communication Technologies is currently writing a new digital practices code that will address the regulation of hosting and cloud computing activities. Under this, service providers will be licensed by the government to operate.

For data centers, the government has a secure center that all agencies can use, and it is reliable – more so than even most of the private in-country service providers. This data center is hosted at the Ministry of Communication Technologies’ Centre National de l’informatique (CNI). Due to the investments data centers require, including operating costs related to energy, the Tunisian government is leaning toward having its own government cloud service. Telecom operators based in Tunisia offer hosting on highly secure in-house data centers that are compliant with international standards. Therefore, the private sector hosts and manages its information systems locally. However, the quality of the service offered is not ideal as there may be service interruptions, and the cost of the service is above the international average.

The deployment of a high-speed internet communication network is a major development challenge for Tunisia. The campaign to increase the number of households with access to the Internet is still far from the target of 100% that was set for 2020, and tellingly in the “network” section of the Levels of e-government exercise conducted for this article, Tunisia comes in last among the four countries.52 Tunisia relies on telecommunication operators (Orange, Ooredoo, Tunisia Telecom) to invest and develop that infrastructure over time, but given the small size of the market, there is little incentive for these operators to make investments for better service delivery.

Tunisia is a case where the varied nature of the indicators included in the indices (i.e., enabling factors such as level of education and the legal framework) yields a high aggregate score but obfuscates a problem that remains to be solved – fragmentation of approaches and slow progress in operational terms.

Discussion

The Levels of e-government framework utilized in this article allow for an overview comparison of the four countries’ performance across an objective set of critical service functions, stripping away more normative elements. For every level, indicators that measure the operational readiness of the government's systems and technology infrastructure were sourced from existing indices and then normalized (as detailed in the Methodology section and Annex 1).

Informed by the qualitative assessment of the four country case studies, the overview comparison of indicator performance developed at the beginning of this paper has been adjusted to measure performance related to the levels of e-government. Table 2 below presents the modified ranking and scores for the four African leaders. Equal weight is placed on each level (front-office, back-office, data exchange, infrastructure and networks).

As mentioned, cross-cutting dimensions such as digital skills or civic participation are not captured in the framework. An additional cross-cutting dimension worth mentioning is that of political will. All four countries have demonstrated some degree of commitment to undertake e-government reforms and policies, but some are more engaged than others. For example, South Africa’s digitization efforts are a subset of its strong economic fundamentals, whereas Seychelles and particularly Mauritius have purposefully targeted e-government as a key lever for their national development agendas.53 Tunisia lags in terms of demonstrated political will to place e-government at the center of the public policy agenda.

When adapting the data to the Levels of e-government framework, the four countries’ ranks relative to each other change slightly, with Mauritius surpassing South Africa, and Tunisia overtaking Seychelles. The challenges South Africa faces with its overlapping agency mandates and data security accounts for the first shift. In the second case, it is the data exchange and data center functions, more developed in Tunisia, that allow the North African country to overtake Seychelles. Proving the management consulting rule that "strategy is what you don’t do,” and constituting a testament to the vast undertaking that e-government represent: None of the countries have it all. Even in Mauritius, digitalization of personal data lags: Despite being a global financial center, banks are still required to keep paper-based records for certain transactions.

Table 2.

"Levels of e-government" index score for case study countries (out of 100)

| Country | Front-office score | Back-office score | Proto-cols score | Cloud services score | Network score | Levels of e-gov score | Levels of e-gov rank | EGDI rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mauritius | 95 | 97 | 37 | 100 | 85 | 83 | 1 | 2 |

| South Africa | 87 | 88 | 34 | 100 | 70 | 76 | 3 | 1 |

| Tunisia | 83 | 87 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 70 | 8 | 4 |

| Seychelles | 73 | 80 | 22 | 0 | 90 | 53 | 16 | 3 |

Recommendations

African countries that want to maximize benefits from investments in e-government should take a modular approach. For example, national policymakers can select one “Level” of e-government where they are strongest and focus there. They should look not at one model (e.g., the “Rwanda” or “Estonia” model) but at specific solutions designed to achieve functions – and invest according to the priority they place on those functions. While this recommendation may appear to contradict the received wisdom today, which is to take a whole-of-government approach, the truth is that a whole-of-government approach takes years, and citizens and businesses want better services now. The Levels of e-government framework can help identify areas, such as data exchange, which require the participation of all agencies, while allowing local government, line ministries and specialized agencies greater flexibility to choose how they want to approach other functions (such as the front- or back-office interface).

Policymakers interested in achieving better user experience for their citizens and businesses can use the Levels of the e-government framework as a guide, starting from the top and going to the bottom. This is also referred to in e-government circles as working “from the outside in,” given that the front-office interface serves as the point of contact between outside constituents and the government.54

- Interfaces The first step is to look at information display, document submission, application review and communication of decisions. All of these are front- and back-office functions that need neither be expensive nor vary greatly from one agency to another. For example, like the “buy now” button on Amazon or the “to-from” fields on travel websites, we recommend a simple sequence, such as “form, docs, sign, pay, submit,” for government websites that allow users to ask for and receive what they need. The interface level is often seen as unimportant to tech suppliers because it is low-cost. Tech suppliers that work in the e-government sector generally want to make expensive products. However, there is immense opportunity in this layer to improve the quality of services.

- Data exchange. This is where it can get unnecessarily complicated. Many governments struggle to get agreement on data exchange, and even when there is agreement, there are always lagging agencies. Here we can learn from the experience of the Moroccan common business identifier. Of the agencies that claimed they could identify private companies or wanted to (tax, social security, intellectual property, courts, business registry, statistical agency, line ministries), it was determined that none of their databases was complete, and they all had something to gain by sharing information. No one wanted to redesign their database, however, or abide by anyone else’s standards. A “minimum data exchange” platform was built in the cloud, with a total cost of US$30,000. This allowed each agency to post specific information it had, such as owner, physical address, tax ID number, date of creation, etc. for businesses. All agencies saw a benefit, and today the “common” number generated by the platform has superseded any single number used by the participating agencies, to become the one that must appear on a receipt for it to be valid for tax purposes. Though the process took ten years to reach fruition, the common number was operational within three months, which was of great benefit for those agencies that needed it urgently. Going forward, each agency pursued its mandate with its data, accessed other data as needed, and the common database grew until it became the “single source of truth” for business identification, where before there was none as all the databases were incomplete (even tax identification).

- Infrastructure. This layer necessitates the biggest investments and can be quite politically sensitive. For example, countries like Algeria and Argentina refuse to use private “cloud” services and have built their own. On the other hand, local governments in the United States are becoming more and more willing to outsource storage to private providers - albeit in their own country. In Africa, there have been and probably will be more, large investments in cables as well as mobile infrastructure – strategies relating to these may be best developed at the continental and regional level. That said, micro-solutions exist that may be appropriate for rural areas with low bandwidth, or, conversely, the software can be designed to work offline in recognition of the bandwidth challenges that exist in some areas.

The final benefit of taking a modular approach to designing e-government systems is that it economizes resources. Whole-of-government approaches are, by definition, expensive. And, as discussed above, foundational investments in e-government require vast sums of money and take years. Meanwhile, if we look at how e-commerce is developing globally, it is possible to envision user-friendly, low-cost technical solutions for delivering easy administrative transactions. That is, if governments want to.

Conclusion

By delving into the global e-government indices and comparing sub-indicator scores across levels and functions of e-government, we were able to isolate e-government performance from e-government foundational conditions. The analysis shows that a significant portion of high performance on the indices can be attributed to “foundational” factors such as infrastructure, skills and the legal and regulatory framework. This is the case for Tunisia and Seychelles, whose scores fall when adjusted to consider only operational performance in providing e-government services. Mauritius rises to first among the four when operational criteria are prioritized. South Africa remains high, showing a balance between foundational and operational factors.

Given the time and resources necessary to advance all of the conditions (foundational and operational), African leaders will want to consider specializing in one or another e-government function. Estonia, for example, exports many e-government services, especially data exchange. The Estonian government originally developed its famous X-road data highway as an attempt to stop agencies from duplicating databases. The country passed a law forbidding agencies to build a new database if the data in question was already contained in another agency’s data storage system, and instead requires them to build a connection.55

Not all innovation requires legislation. Morocco was a pioneer in effective G2B services based on two simple things: (a) a standardized method for organizing the requirements for submission of an application, and (b) a common business identifier that allowed agencies to fetch data on companies and compare their status. Fifteen years later, that method for organizing information has been disseminated to more than 24 African countries by the United National Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) in the form of the e-Regulations trade portals.56

Finally, as stated in the opening paragraph of this article, e-government is part of the overall global digital transformation and contributes directly to growth. Today in developed countries, banks with outdated systems are raising capital to finance their migration to the cloud and the development of global, customer-friendly solutions. Across Africa, banks are working with governments to improve how their employees can view data related to branches in other countries without having to log off and back on. The challenge then, is not only how governments can deliver better e-services, but how they can best partner with private enterprises to innovate.

Realizing the potential of e-government in Africa will require creative strategies. A first, constructive step is to break the vast field of e-government down into smaller, more manageable chunks, and consider specializing in one functional area, type of service or layer of the technological stack in a way that builds on each country’s comparative advantage (including human capital and language). In less developed countries, e-government service delivery strategies can be low-cost, use technologies appropriate for rural areas with low bandwidth and be designed to serve populations with lower digital and functional literacy levels. At the other end of the spectrum, countries like South Africa that are already using advanced technologies in their manufacturing and professional service sectors are well-placed to identify, develop and exploit innovative solutions using artificial intelligence and the Internet of Things.

For countries that have not yet fully digitized, there is a one-time opportunity to bypass heavy, outdated back-office systems by using standard API protocols, plug-ins and secure cloud services. Pressure to keep costs low seems like a disadvantage now but could become an advantage if they drive innovation. At the end of the day, what determines countries’ success in e-governance may be less related to whether public agencies can move in lockstep, or how they choose to share data, than simply whether they are asking the question, “What is it that citizens and business users need, and how can it be offered in a simple, low-cost way?”

Table 3.

Annex 1 "Levels of e-government" indicator list

| E-GOVERNMENT LEVELS | INDICES | INDICATORS |

|---|---|---|

| Front-office indicators | E-Government Development Index, Online Services Index | Service provision |

| Content provision | ||

| Technology | ||

| GovTech Maturity Index, Public Service Delivery Index | Is there an online public service portal (one stop shop)? | |

| Is there a tax online service portal? | ||

| Is e-filing available for tax and/or customs declarations? | ||

| Are e-payment services available? | ||

| Is there a customs online service portal? (single window) | ||

| Is there a social insurance/pension online service portal? | ||

| Is there a job portal? | ||

| GovTech Maturity Index, GovTech Enablers Index | Is there a foundational unique national ID? | |

| Is there a digital ID used for identification and online services? | ||

| Back-office indicators | E-Government Development Index, Online Services Index | Institutional framework |

| GovTech Maturity Index, Core Government Systems Index | Is there an operational FMIS (financial management information system) to support core PFM (public financial management) functions? | |

| Is there a TSA (treasury single account) supported by FMIS to automate payments and bank reconciliation? | ||

| Is there a tax management information system in place? | ||

| Is there a customs management information system in place? | ||

| Is there a human resources management information system (HRMIS) with a self-service portal? | ||

| Is there a payroll system (MIS) linked with HRMIS? | ||

| Is there a social insurance system (non-health) providing pensions (including public sector) and other SI programs? | ||

| Is there an e-procurement system? | ||

| Is there a debt management system (DMIS) in place? (Foreign and domestic debt?) | ||

| Is there a public investment management system (PIMS) in place? | ||

| Is there a government open-source software policy/action plan for public sector? | ||

| Protocols indicators | GovTech Maturity Index, Core Government Systems Index | Is there a whole of e-government approach to public sector digital transformation? |

| Is there a government enterprise architecture framework? | ||

| Is there a government interoperability framework? | ||

| Is there a government service bus (GSB) platform? | ||

| GovTech Maturity Index, GovTech Enablers Index | Is there a digital signature regulation and PKI (public key infrastructure) to support service delivery? | |

| National Cyber Security Index, Protection of digital services | Cybersecurity responsibility for digital service providers | |

| Cybersecurity standard for the public sector | ||

| Competent supervisory authority | ||

| National Cyber Security Index, Protection of essential services | Operators of essential services are identified | |

| Cyber security requirements for operators of essential services to manage ICT risks | ||

| Competent supervisory authority | ||

| Regular monitoring of security measures | ||

| National Cyber Security Index, E-Identification and trust services | Unique persistent identifier | |

| Requirements for cryptosystems | ||

| Electronic identification | ||

| Electronic signature | ||

| Timestamping | ||

| Electronic registered delivery service | ||

| Competent supervisory authority | ||

| Cloud services indicators | GovTech Maturity Index, Core Government Systems Index | Is there a shared cloud platform for all government entities? |

| Data centers indicators | n/a | n/a |

| Network indicators | E-Government Development Index, Telecommunication Infrastructure Index | Individuals using the Internet as % of population |

| Wireless broadband subscriptions per 100 | ||

| Fixed telephone subscriptions per 100 | ||

| Mobile cellular subscriptions per 100 |

About the Authors

Lara Goldmark

Lara Goldmark is currently founder and CEO of Just Results, a company that uses data to support inclusive economic growth, Lara is an economist with specialization in regulatory reform and digital solutions for government.

Hamza Denguezli

Hamza Denguezli is a Tunisian research analyst. At Just Result’s startup, ZGov he recently worked in the field with the private sector to mapping administrative procedures and then with government users of the ZForm solution to adapt it to their needs.

Jorge Alarcón Martin

Jorge is a multidisciplinary professional with several years of experience across consulting and research roles. Fluent in Spanish, English and French, he has acquired relevant experience in fields such as sustainable and international development, evaluations, notably impact investing and impact measurement and management.

Endnotes

1Tang, & Bentil. (2022, July 15). Empowering Africa’s youth to thrive in a digital economy. World Bank, from https://blogs.worldbank.org/education/empowering-africas-youth-thrive-digital-economy#:~:text=Given%20the%20ubiquity%20of%20mobile,them%20to%20appropriate%20job%20opportunities

2Fintech is key for financing Africa’s digital transformation | United Nations Economic Commission for Africa. (2021, December 3), from https://www.uneca.org/stories/fintech-is-key-for-financing-africa%E2%80%99s-digital-transformation#:~:text=,19%20Development%E2%80%99

3Empowering Africa’s young people in the digital economy. (2019, December 19). International Trade Center. Retrieved January 2, 2024, from https://intracen.org/news-and-events/news/empowering-africas-young-people-in-the-digital-economy#:~:text=19%20December%202019%20Ibrahima%20Nour,the%20economies%20on%20the%20continent

4Digital Transformation Strategy for Africa . (n.d.). African Union, from https://au.int/sites/default/files/documents/38507-doc-dts-english.pdf

5Barasa, H. (2022, March 14). Digital Government in Sub-Saharan Africa: Evolving Fast, Lacking Frameworks. https://www.institute.global/insights/tech-and-digitalisation/digital-government-sub-saharan-africa-evolving-fast-lacking-frameworks

6Barasa, H. (2022, March 14). Digital Government in Sub-Saharan Africa: Evolving Fast, Lacking Frameworks. https://www.institute.global/insights/tech-and-digitalisation/digital-government-sub-sahaan-africa-evolving-fast-lacking-frameworks

7Mahlangu & Ruhode. (N.d.) Factors Enhancing E-Government Service Gaps in a Developing Country Context. Cape Peninsula University of Technology and Midlands State University, from https://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/2108/2108.09803.pdf

8Ouedraogo, & N Sy. (2020, May 29). Can digitization help deter corruption in Africa? International Monetary Fund. from https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2020/05/29/Can-Digitalization-Help-Deter-Corruption-in-Africa-49385

9New Initiative on Digital Transformation with Africa. (2022, December 14). The White House. Retrieved January 2, 2024, from https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/12/14/fact-sheet-new-initiative-on-digital-transformation-with-africa-dta/

10From Connectivity to Services: Digital Transformation in Africa. (2023, June 26). The World Bank, from https://www.worldbank.org/en/results/2023/06/26/from-connectivity-to-services-digital-transformation-in-africa

11X-Road - e-Estonia. (2023, November 13). e-Estonia. https://e-estonia.com/solutions/interoperability-services/x-road/

12Pollitt, Christopher. 2003b. Joined-up Government: A Survey. Political Studies Review 1: 34– 49.

13The United States is a case in point. A business operating in Maryland with offices in the District of Columbia (DC) must navigate multiple websites within the DC government, creating accounts on each one, in order to (a) obtain information, (b) register, which requires a local resident to be a shareholder or serve as an agent, and later (c) periodically update information, once registered.

14World Bank. (2019). South Africa Digital Economy Diagnostic. Washington D.C.: World Bank Group

15Home. DHA. (n.d.). https://ehome.dha.gov.za/ehomeaffairsv3

16Home Page - eTenders Portal. (n.d.). https://www.etenders.gov.za/

17Welcome - central supplier database application. Welcome - Central Supplier Database Application. (n.d.). https://secure.csd.gov.za/

18Services. e. (n.d.). https://www.eservices.gov.za/

19South Africa - Digital Economy Diagnostic. (2019, December). The World Bank, from https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/464421589343923215/south-africa-digital-economy-diagnostic

20South Africa - Digital Economy Diagnostic. (2019, December). The World Bank, from https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/464421589343923215/south-africa-digital-economy-diagnostic

21South Africa - Digital Economy Diagnostic. (2019, December). The World Bank, from https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/464421589343923215/south-africa-digital-economy-diagnostic

22Welcome to Sita | Sita. (n.d.). https://www.sita.co.za/

23South Africa - Digital Economy Diagnostic. (2019, December). The World Bank, from https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/464421589343923215/south-africa-digital-economy-diagnostic

24Data Collection Survey on Digitalization of Public Services in African Countries. (2022, March). In Japan International Cooperation Agency., from https://openjicareport.jica.go.jp/pdf/12369013.pdf

25DPSA. (2017). Minimum Interoperability Standards (MIOS) Framework For Government Information Systems. Pretoria: DPSA. https://www.sita.co.za/sites/default/files/documents/MIOS/Searchable%20-%20MIOS%20Framework%20V6%200.pdf

26National e-government strategy and roadmap. (2017, November 10). Telecommunications and postal services, Republic of South Africa, from https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201711/41241gen886.pdf

27Infrastructure Project Preparation Facility. PIDA. (2023, December 15). https://www.au-pida.org/nepad-infrastructure-project-preparation-facility/

28Japan International Cooperation Agency. (2022). Data Collection Survey on Digitalization of Public Services in African Countries. Final Report. Tokyo: JICA.

29Independent Communications Authority of South Africa ICASA. Icasa.org.za. (n.d.). https://www.icasa.org.za/

30Department of Communication and Digital Technologies . (n.d.). Retrieved January 2, 2024, from https://www.dcdt.gov.za/sa-connect-document.html

31USAASA - Strategic overview. (n.d.). http://www.usaasa.org.za/about/strategic-overview.html

32World Bank (2019) South Africa Digital Economy Diagnostic. Washington D.C.: World Bank Group

33Mauritius Artificial Intelligence Strategy 2018

34InfoHighway - Data Sharing Platform. (n.d.). https://ih.govmu.org/

35National Computer Board. (n.d.). https://ncb.govmu.org/ncb/govtcloud.html

36Ministry of Technology, Communication and Innovation (2017) National Open Data Policy https://president.govmu.org/Documents/Strategies/Mauritius%20Open%20Data%20Policy%20May%202017.pdf

37Open data Mauritius. (n.d.). https://data.govmu.org/dkan/

38World Bank. (2022). Mauritius – Systematic Country Diagnostic (SCD) Update. Washington D.C.: World Bank Group.

39World Bank. (2018). Digital government in Seychelles. Analysis and Recommendations. Washington D.C.: World Bank Group; The Commonwealth. (2016). Case Study 5.2. Seychelles. e-government development and implementation: Lessons for small island developing states (pp. 188-204), in Key principles of public sector reforms. Caser studies and Frameworks. London: Commonwealth Secretariat

40World Bank. (2018). Digital government in Seychelles. Analysis and Recommendations. Washington D.C.: World Bank Group

41World Bank. (2018). Digital government in Seychelles. Analysis and Recommendations. Washington D.C.: World Bank Group; The Commonwealth. (2016). Case Study 5.2. Seychelles. e-government development and implementation: Lessons for small island developing states (pp. 188-204), in Key principles of public sector reforms. Caser studies and Frameworks. London: Commonwealth Secretariat

42World Bank. (2018). Digital government in Seychelles. Analysis and Recommendations. Washington D.C.: World Bank Group

43Government of Seychelles - downloadable forms. (n.d.). https://www.egov.sc/Forms/FormsAtoL.aspx

44Macdonald, Ayang. (2021). Travizory revolutionizing border security management through biometrics. Biometric update. https://www.biometricupdate.com/202112/travizory-revolutionizing-border-security-management-through-biometrics, accessed 21 December 2022

45World Bank. (2018). Digital government in Seychelles. Analysis and Recommendations. Washington D.C.: World Bank Group

46Performance Monitoring & Evaluation Manual - psb.gov.sc. (n.d.-a). https://www.psb.gov.sc/sites/default/files/documents/Seychelles%20Performance%20M&E%20Manual%20-%20October%202020.pdf

47World Bank. (2018). Digital government in Seychelles. Analysis and Recommendations. Washington D.C.: World Bank Group

48World Bank. (2018). Digital government in Seychelles. Analysis and Recommendations. Washington D.C.: World Bank Group; The Commonwealth. (2016). Case Study 5.2. Seychelles. e-government development and implementation: Lessons for small island developing states (pp. 188-204), in Key principles of public sector reforms. Caser studies and Frameworks. London: Commonwealth Secretariat

49Tunisia 609(G) CN - Millennium Challenge Corporation. (n.d.-b). https://assets.mcc.gov/content/uploads/cn-121018-tunisia-compact-609g.pdf

50Plan de mobilisation des parties prenantes mise a jour. (n.d.-b). http://www.santetunisie.rns.tn/images/pmpp-2021.pdf

51Interview with Zakaria Karim Mekni, owner of Sirat, a company that provides technology services to the government.