The Covid-19 pandemic has shone a spotlight on the digital economy due to an increased reliance on digital platforms to conduct business online. Countries are also looking to increase revenue collection to recover from government spending throughout the pandemic. Discussions around a global solution to taxing the digital economy have intensified. On 8th October 2021, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) provided a detailed implementation plan of a two pillar solution that has been agreed on by 136 countries. The new proposals attempt to simplify the two-pillar solution, agreed upon in July 2020, that presented potential rules for addressing nexus and profit allocation challenges (Pillar One) and for global minimum tax rules (Pillar Two). The proposals were backed by the United States (U.S.) and have been agreed upon by 136 countries of the OECD inclusive framework (IF), including all EU IF member states and 23 of the 25 African IF member states. The new pillar one proposes the reallocation of taxing rights among states and captures the largest and most profitable Multinational Enterprises (MNEs). Taxing rights are redistributed to market countries where MNEs derive revenue above EUR 1 million (for larger economies) and EUR 250,000 (for smaller economies). The agreement reallocates 25% of residual profits to market jurisdictions with nexus using a revenue-based allocation key. Pillar two proposes the introduction of a minimum tax of 15% for MNEs that have more than EUR 750 million in global revenue. Pillar one will be compulsory for all participating countries, whereas pillar two represents a ‘common approach’ in which the rules are not compulsory. Any state that chooses to adopt them is required to implement the rules in a manner consistent with the intentions of pillar two. Those that do not implement pillar two must accept the application of these rules by the countries that choose to adopt them.

The implementation plan published by the OECD sets out an ambitious timeline for implementation of the rules within the next two years. The agreement comes after several years of intense negotiations between countries and jurisdictions that represent more than 90% of global GDP.

The European Commission (EC) and 22 EU member states participate in the OECD and have all expressed support of the two-pillar solution. The EC considers the agreement as a key step towards the implementation of global tax reform. Unsurprisingly, plans to introduce an EU-wide digital tax for large tech companies and to replace levies introduced by some of its members were placed on hold as the EC waits for the implementation of the multilateral solution to determine whether further reform will be needed. The proposed digital levy is indicative of the Commission’s concerns over the taxation of digital MNEs who do not maintain any physical presence in member states. Intended to come into effect in 2022, the levy would be in line with the EU’s tax and trade obligations that guarantee the free movement of goods, capital, services and people within the single Market. In the meantime, the EC is pushing for matters that specifically concern its member states, such as the single market compatibility of the proposals and the reduction of administrative complexity.

The challenges presented to African countries by the digital economy have been exacerbated by legislative and administrative constraints faced by the continent.

Most African countries in the IF, as well as the African Tax Administration Forum (ATAF), have expressed their support of the OECD unified approach proposals with the exception of Kenya and Nigeria. Nigeria has stated that current conditions do not provide a fair deal for the equitable reallocation of profits to all market jurisdictions, listing the limited scope of amount A, proposals for binding arbitration and the potential withdrawal of all unilateral taxation measures for companies without a physical presence in Nigeria as concerns. In its statement, the ATAF commended that U.S. backed proposals called for a simplification of pillar one, yet it proposes that redistribution should be based on total profits and not be limited to residual profit. In a statement issued on 19 September 2021, G24 countries including Nigeria and Kenya, expressed disappointment in the exclusion of their proposals to consider deemed return in the calculation of Amount A, but emphasized that for the current proposals to be effective, the reallocation of the non-routine profit earned by multinationals should be 30%. The G24 and ATAF hold the position that countries with limited capacities and low levels of MAP disputes should have access to an elective, non-binding dispute resolution mechanism. The ATAF statement also advocates for a higher minimum tax and the application of the Undertaxed Payment, which has met resistance from developed countries. While G24 countries also advocate for a higher minimum effective tax and a high minimum rate on gross revenue under the Subject to Tax Rule (STTR), the countries call for this to be applied to payments for services and capital. Furthermore, the G24 favours a gradual withdrawal of unilateral measures and assurance of sufficient revenue under pillar I and II.

Another concern raised by policy experts is the impact of minimum tax on the incentive regimes of developing countries. If introduced, countries may be required to repeal these regimes in order to bring their effective tax rates closer to the agreed minimum tax. Incentives are easy to repeal if contained in tax laws and investment treaties, yet a number of developing countries are committed to agreements in which tax incentives are locked in through fiscal stabilization clauses that freeze fiscal terms to the time of signing. This means that changes in tax law will not apply to existing investments. These incentives reduce the effective tax rate and, based on the minimum tax proposals, the home state would have the right to tax the revenue derived from those states. It would therefore be necessary for countries to agree on amendments to treaties that contain stabilization clauses.

Although the African Union’s (AU) involvement in tax policy is limited, ministers have emphasized the importance of a unified African approach by calling for its member states to actively participate in IF debates. Like the ATAF, the AU maintains the view that amount A should not exclude small economies, that amount B should be broad enough to provide meaningful tax, that no mandatory binding dispute resolution mechanism should exist and that a source-based rule should form the primary principle of pillar 2.

Bridging the gap

Both the EU and Africa have an agreed objective of taxing digital MNEs operating without physical presence in their respective jurisdictions. The ATAF has called for the distribution of total profits rather than the distribution of residual profit. This is similar to the Business in Europe: Framework for Income Taxation (BEFIT) proposal of the EU. The BEFIT will adopt a single set of rules to determine the specific tax liability of each member state in order to generate a single EU corporate tax return. While the BEFIT is similar to the proposals of the ATAF, the distribution of total profits will likely be easier for the EU as a single market than the diverse economic profiles and administrative capacities of the 136 countries. This demands a level of global cooperation at odds with current economic realities.

The OECD has stated that the multilateral convention to be introduced for the implementation of Amount A will include an elective binding dispute resolution mechanism for developing countries that are eligible to defer BEPS action 14 peer review and have little to no mutual agreement procedure (MAP) disputes. This comes as a relief for G24 countries and ATAF, as many developing countries regard the arbitration processes as lacking in transparency, hindering the potential to learn from experience or to monitor the effectiveness of such processes in the first place. As a result, they will be pitted against developed countries with more arbitration experience unless the process is genuinely tailored to meet the needs of all participating parties. Alternatively, the EU could push for arbitration to be structured in a way that ensures the rights of developing countries, including the regionalization of arbitration centres and increased transparency.

African countries will need support from the EU and other developed countries to unwind tax incentives that are bound by stabilization clauses within trade and investment treaties and contracts. This would ensure that developing countries do not lose revenue in two ways: tax revenue foregone through incentives and tax to developed countries through the income inclusion rule. They would be able to modify their agreements to bring stabilized tax incentives into conformity with minimum tax rules.

Additionally, implementation of the undertaxed payment rule and the subject to tax rule is likely going to lead to increased administrative burden on tax authorities in Africa. These countries will therefore need technical assistance in order for them to fully benefit from the two-pillar solution.

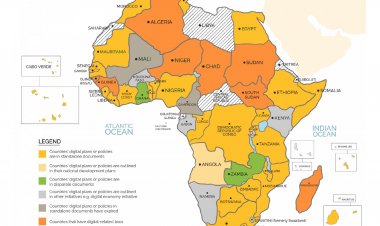

While multilateral proposals may not address all of the priorities of African countries, they do provide a good starting point for further discussions. Even so, it is important to appreciate that only 23 of the 55 countries in Africa are members of the IF (more than half) have not expressed their agreement to the two-pillar solutions. Regardless, Africa will need support from the EU and other developed countries in having its concerns addressed and represented in a sustainable solution for all.

About the Author

Ruth Wamuyu has over five years’ experience in tax consultancy and research. She has previously worked as a research associate at the Strathmore Tax Research Centre. She also worked as a tax associate at KPMG Kenya. During her time at KPMG she focused on tax advisory both domestically and internationally. Ruth also worked at Iseme, Kamau and Maema Advocates as a trainee advocate. In addition, she has independently taken part in research projects on financial secrecy in East African countries and a case study on the use of litigation as a tax policy reform tool. Ruth completed her LLM in International Tax Law from King’s College London, her Bachelor of Laws degree from Strathmore University Kenya, and is admitted to the bar in Kenya.