Summary

- The current international tax rules for the digitalised economy stipulate that Multi-National Enterprises (MNEs) only pay taxes in countries where they have a physical presence. MNEs that operate digitally and remotely in African countries are exploiting this loophole and avoiding taxes in such market jurisdictions.

- Towards remedying this situation, African countries partnered with other stakeholders under the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework (IF) on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) to curb the widespread tax avoidance and profit shifting by MNEs.

- While members of the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework (IF) were working on these reforms, the US proposed new amendments to the minimum corporate tax rate and arrangements for taxing multinationals. The G7 adopted the US amendments. Subsequently, 130 of the 139 members of the OECD Inclusive Framework too endorsed it.

- Nigeria refused to endorse the US’s unilateral proposals and, like other African countries, decried the new the minimum corporate tax rate as low. The new rules threaten to further deteriorate the already low revenue tax positions of African countries.

- Although the G7 countries constitute only 10% of the world's population, their proposal stands to adversely influence over 200 tax jurisdictions that rely heavily on corporate tax revenue. Tax justice campaigners and African countries are advocating for a more equitable and just digital tax regime.

Introduction and background

The current international tax rules for the digitalised economy pose some challenges for African countries. Notably, they stipulate that a Multi-National Enterprise (MNE) can only be taxed in countries where they maintain some form of physical presence — see Article 5 of the OECD Model, which corresponds to the African Tax Administration (ATAF) Tax Treaty Model.

Technological advancements have made it possible for MNEs to operate digitally and remotely in African countries without any local physical presence. Some MNEs exploit this loophole because there is no legal obligation to pay tax in such market jurisdictions. While some pay taxes in their home countries, others avoid paying income tax anywhere in the world. This loophole poses extreme difficulty for tax administration in Africa. It deprives African governments of their due tax revenue and potential employment opportunities. Furthermore, the exchange of skills and technologies that would otherwise emerge from an MNE's physical presence in Africa do not occur.

For the MNEs that maintain a physical presence in Africa, tax revenue has increasingly diminished due to a culture of competition between countries, both continentally and internationally, to attract Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) by minimizing the corporate taxes that MNEs are required to pay, generating the proverbial race to the bottom.

These problems exist on a global scale and are not unique to African countries alone. Since Africa cannot influence international tax rules independently, African countries have worked with other stakeholders worldwide to address these challenges. They joined other countries under the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework (IF) on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) to institute actions targeted at curbing tax avoidance in the digitalised economy and levelling the playing field.

Taxing the Digitalised Economy

For African countries, a favourable solution would be one that enables the continent to tax MNEs that it currently cannot tax because they do not have a physical presence, which ends the race to the bottom. Accordingly, the OECD Secretariat's Pillar 1 and Pillar 2 proposals were initially seen as a welcome development. Originally, Pillar 1 was designed to create a new taxing nexus rule that would operate regardless of whether an MNE has a physical presence in a country. Pillar 2 was to establish a global minimum Effective Tax Rate (ETR) to end the race to the bottom on corporate tax rates and deal with other outstanding sundry BEPS issues.

The original scope of the Pillar 1 proposal was enterprises with a consolidated global turnover of more than USD 750 million. This arrangement put thousands of companies within the scope of this rule. The enterprises were further divided into Automated Digital Services (ADS) and Consumer Facing Businesses (CFB). The initial deadline to finalize this work was set for the year 2020. However, this was extended until 2021 due to delays and shifts incurred because of the United States' political dynamics and the Covid-19 crisis.

The G7 Proposal

Following the change of government in the United States, in early 2021, the US presented a proposal objecting to the dichotomy between ADS and CFB, describing it as discriminatory to their interests. They amended the scope of Pillar 1 to cover only 100 MNEs, disregarding whether they fall into the ADS or CFB categorization in favour of what was termed "comprehensive scoping". They also set the revenue and profitability thresholds to USD 20 billion and 10%, respectively.

The US proposal also contained a provision for mandatory binding arbitration. This dispute resolution mechanism would subject tax disputes arising from the implementation of these rules and associated issues to a settlement procedure similar to those obtained under international trade arrangements. They also proposed a rollback or stand still on unilateral measures taken by stakeholders seeking to address the tax challenges posed by the digitalised economy. The minimum effective tax rate for Pillar 2 was set at 15%. The primary rule for Pillar 2 remained the Income Inclusion Rule, ensuring that the home country of an MNE is the beneficiary of any income of the MNEs not taxed up to the agreed global minimum tax rate in the market jurisdictions.

The G7 adopted this proposal designed by the US. It became the basis for the work on the digitization of the economy, rendering the vital elements of the IF/OECD blueprints that members had spent years working on redundant.

On 1 July 2021, 130 of the 139 members of the OECD Inclusive Framework endorsed the US-led G7 proposal, with the notable exception of Nigeria and a few others. More countries have since joined the Agreement. Analysis suggests that this endorsement is a product of an unequalled diplomatic manoeuvre between political heavyweights led by the US and the G7.

Political Economy

The international tax architecture for the digitalised economy's taxation does not favour the market jurisdictions – which happen to be predominantly developing countries. The OECD has led work on setting global tax rules for decades. While the political commitment showed by the G7 towards major international tax reforms and facilitated by the OECD is commendable, critics have raised concerns about the influence of developed nations in setting standards for international taxation.

This is because the MNEs who have benefitted from the existing rules are mostly headquartered in developed countries. A key issue would be whether developing countries, though part of the ongoing work, could influence the desired outcome for Africa. The refusal of Kenya and Nigeria to sign the Inclusive Framework statement on the piece paints a different picture.

While the G7 countries constitute only 10% of the world's population, their proposal will influence over 200 tax jurisdictions. According to Tax Justice Network estimates, the G7 will receive 60% of the additional revenue on Pillar 2, leaving only 40% to the remaining world population (90%).

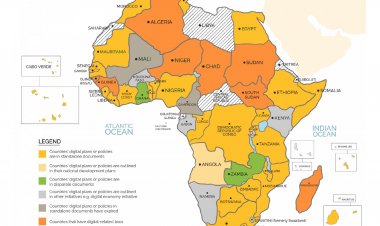

From the 26 African members of the Inclusive Framework, Nigeria, South Africa, Ivory Coast and Senegal are in the Steering Group. Additionally, some countries have also joined pressure groups like the G24 and ATAF. With this level of participation, Africa undeniably has a strong presence. However, it remains to be seen whether this is reflected in its capacity to achieve its desired outcomes in the ongoing work.

The task of developing the rules for taxation of the digitalised economy is still ongoing. But the refusal of some leading economies in Africa to sign unto the IF July statement could be read as a sign of how far the continent is from finding a lasting solution to the challenges of taxing companies drawing huge tax-free revenues from its jurisdiction by maintaining no physical presence there.

Therefore, it may be useful to revisit alternative solutions proffered by international organizations like the UN tax committee and the ICRICT. It is also noteworthy that the FACTI panel, among others, has been advocating for a global tax body under the auspices of the UN in a bid to provide more legitimacy, equity, and inclusiveness.

The implications of the rates and threshold for developing economies

Revenue and profitability thresholds have been proposed to determine the Multi-National Enterprises (MNEs) that will pay tax under Pillar 1. Of particular interest to Africa is the G7's proposal of a 15% Effective Tax Rate (ETR) as a minimum tax rate under Pillar 2. What implications does this hold for Africa? And how will it influence the scoping threshold for Pillar 1?

Some analysis gives the average corporate tax rate for Africa as 27.46%, tax incentives, giveaways and loopholes result in a far lower effective tax rate for African countries. For instance, with a nominal tax rate of 30%, where the actual profit of an MNE could not be established, the Nigeria tax authorities, under its laws, subject such companies to a deemed profit taxation which results in an ETR of only 6%. This meant that, as far as Nigeria is concerned, the difference between the proposed global minimum effective tax rate of 15% and the 6% ETR will be taxed by the country of residence of the MNE group using the Income Inclusion Rule. This generates a situation for developing countries in which they have to shore up their ETR by overhauling their tax incentive regimes and retooling domestic legal framework for more effective taxation of MNEs to avoid losing a significant portion of their tax right/base to a developed country.

Interventions aimed at restructuring tax incentive regimes must cover domestic tax laws and tax-related incentives within the context of International Investment Agreements (IIAs). These Agreements are usually fraught with stabilization clauses that guarantee a set standard of regulatory treatment to investments made pursuant to the Agreement. Some such clauses forbid the host nation from withdrawing certain incentives guaranteed under the IIA or otherwise established at the time of the investment. Though removing these kinds of tax incentives may be difficult, maintaining such boundaries may be less attractive to the MNEs if all IF members implement the Income Inclusion Rule. This is because the MNEs will not benefit from the incentive since it would be taxed in its home jurisdiction.

Under Pillar 1, revenue and profitability thresholds were set at USD 20 billion and 10%, respectively. These thresholds do not cover most MNEs operating in African markets because they offer automated digital services or lack any physical presence or nexus. Therefore, they do not pay taxes in those jurisdictions. A country hosting its headquarters locally may apply IIR to MNEs at a threshold less than those prescribed above. However, this rule does not bear much relevance to Africa, as a few of the relevant MNEs are headquartered in the continent.

Finally, removing unilateral measures like Digital Service Taxes (DST) and Significant Economic Presence (SEP) rules have been proposed as a precondition for implementing Pillar 1. Suppose we take into consideration that what constitutes unilateral measures is broadly defined. In that case, it may hinder how certain countries currently tax non-resident MNEs, including MNEs not in the scope of the Pillar 1 profitability and revenue thresholds. The implication of the above is that while most of the companies conducting business in Africa, especially within the Automated Digital Service sectors, do not operate within the scope of Pillar 1, African countries would still derive little or nothing from its implementation in the first place. Nonetheless, they will be expected to give up some existing taxing rights, potentially leading to negative revenue returns. The implications and challenges arising from this amidst a landscape already complicated by the emergence of COVID-19, rising debt profiles, poverty, and a scarcity of resources in developing nations cannot be overemphasized.

Recommendations

The OECD secretariat, which doubles as the secretariat for the Inclusive Framework, should immediately run an economic impact assessment to lay out what revenue, if any, will be accruable to developing nations from the US-led G7 proposal. Developing countries should consider reviewing and streamlining their tax incentive regimes preparatory to coming into effect of Income Inclusion Rules to shore up their ETR and avert losing their tax basis to developed economies. The G7 should instil more equity in the final design of the rules and ensure that taxing rights of the least developed economies are not taken away under the guise of removing unilateral measures. African countries should continue to participate in the ongoing effort to design rules favourable to their economic context. The final instrument should include an override of guarantees in IIAs that contradict the design and intent of the regulations themselves.

The minimum effective tax rate (METR) proposed by a group of researchers variously affiliated to the Tax Justice Network, the BEPS Monitoring Group, the Independent Commission for the Reform of International Corporate Taxation (ICRICT) and Charles University's CORPTAX research group is currently the most reasonable strategy, particularly for African countries.

The proposal seeks to combine two elements of Pillar 2 rules into a single Formulary Apportionment Rule applicable to inbound and outbound investment alike. It will provide a fairer and more effective solution since it is simpler to apply, non-discriminatory and recognizes a country's right to set its tax rates whilst guaranteeing that incomes are taxed where they are made.

Better representation and equal footing are required within the ongoing negotiation of digitalised economy taxation. African countries should refuse any coercion that would result in the prioritization of political considerations over economic interests. African countries need to speak with one voice, work together more closely, and explore all available options that push for an outcome best suited for their mutual needs and interests. However, given that the current problem requires a global solution, not just African, they must continue to work with other interest groups around the world like G24, G7, ATAF, G20, etc. to push for a more equitable outcome in any global agreement for the taxation of the digitalised economy.

A global tax body under the auspices of the UN will have more legitimacy and provide equity. Developing countries must call for a new UN Tax Convention while initiating an intergovernmental UN tax negotiation to protects countries' tax sovereignty. This will also bring better representation and possibly equal footing.

This policy brief is the result of a collaboration between APRI and the Abuja-based think tank African Centre for Tax and Governance (ACTG)

About the Authors

Mustapha Ndajiwo

Mustapha is the founder and Executive Director of the African Centre for Tax and Governance. (ACTG). He has over eight years of experience as a tax official with the Nigerian Federal Inland Revenue Service (FIRS). He has also served in the capacity of the Technical Advisor to the Executive Chairman of FIRS Nigeria. He was recently a Regional Coordinator for the UN FACTI Panel in Africa.

Learnmore Nyamudzanga

Learnmore is a blogger, economist and fellow at African Centre for Tax and Governance and an intern at the Minerals Africa Development Institution. He is a former economic governance officer at the Zimbabwe Environmental Law Association, former Tax Manager at Trinity Tax Accountants, and Former tax specialist at Zimbabwe Revenue Authority.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Emmanuel Eze for his invaluable contributions to this policy brief.