This article is a part of a series of special thought pieces published by APRI in collaboration with the Deutsche Afrika Stiftung e.V.

Summary

- To reduce its vulnerability and dependence on single country-dominated critical mineral supply chains, the EU has taken initiatives aimed at diversifying its supply of these minerals.

- Memoranda of understanding (MoUs) have been signed with the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Zambia, both rich in copper, cobalt, and other critical raw materials (CRMs), to develop cooperation in five key areas of the CRM value chain.

- The implementation and success of these MoUs will depend in part on the ability of the EU, the DRC, Zambia, and the US to align their agendas: geopolitical priorities for the EU and US, and economic and industrial priorities for the DRC and Zambia.

- The governance challenges in the DRC and Zambia are an important obstacle to overcome to incentivize and guarantee the active participation of private European companies in implementing these agreements.

- Against the backdrop of the West and China’s geopolitical rivalry over the CRM supply chain, China’s presence as the main mining actor in the DRC and Zambia might constitute a stumbling block between the EU on the one hand, and the DRC, Zambia, and European private companies, none of whom have expressed any interest to stop working with China, on the other.

Background

The EU’s Critical Mineral Strategy

In October 2023, at the Global Gateway Forum in Brussels, the European Union (EU) Commission signed two strategic partnerships on Critical Raw Materials (CRM) value chains - one with the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and the other with Zambia. The EU signed a third Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with the United States (US), Angola, the DRC, Zambia, the African Development Bank, and the Africa Finance Corporation to the development of the Lobito Transport Corridor.

Unlike the US, which in December 2022 signed a joint MoU with Zambia and the DRC, the EU has signed two separate MoUs on critical minerals with the two countries. However, the two separate MoUs read the same, cover the same areas of cooperation, and aim to achieve the same overall goals.

Just like the US and other Western countries, EU countries have realized their vulnerability1 to China and other third-party countries regarding critical minerals. Russia’s war in Ukraine, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the current China-US tensions have heightened these vulnerabilities.

In March 2023, the EU Commission proposed the Critical Raw Materials Act, a strategic document that “will equip the EU with the tools to ensure the EU's access to a secure and sustainable supply of critical raw materials”.2 It is presented as a “comprehensive set of actions to ensure the EU's access to a secure, diversified, affordable, and sustainable supply of critical raw materials.”3

In its assessment of the situation, the EU acknowledges its “heavy reliance on imports, often from quasi-monopolistic third country suppliers”4 and the necessity to mitigate the risks related to that dependence.

The president of the EU Commission, Ursula Von Der Leyen, stated that “It [the act] will significantly improve the refining, processing, and recycling of critical raw materials here in Europe. Raw materials are vital for manufacturing key technologies for our twin transition – like wind power generation, hydrogen storage, or batteries. And we're strengthening our cooperation with reliable trading partners globally to reduce the EU's current dependencies on just one or a few countries.”5

In its critical mineral strategy, the EU Commission has updated the Union’s critical mineral list and created a strategic minerals list that comprises sixteen strategic raw materials that are essential for the green and digital transition, as well as for defense and space, and which are also subject to high supply risk, as the EU depends on imports from just a few countries.

A large majority of these minerals are either mined and/or processed in a single third-party non-EU country. In the case of the EU, China is the predominant player in the supply and value chain of these minerals.

With the demand for critical minerals such as lithium, rare earth, nickel, cobalt, magnesium, and copper expected to increase, if no actions are taken, EU countries are likely to increase their dependence on and thus vulnerabilities toward countries like China or Russia.

Though, by 2030, the EU aims to strengthen its own domestic critical supply chain by increasing its mining, refining, and recycling capacities, the EU Commission also acknowledges the inability of member countries to “be self-sufficient in supplying such raw materials and will continue to rely on imports for a majority of its consumption.”6 Thus the need exists to strengthen its global engagement and form strategic partnerships with producing countries.

These agreements are part of the EU strategy’s international engagement to build a more resilient, diversified, and less one-country-dependent critical mineral supply chain.

Why the DRC and Zambia?

In October 2023, when the EU was signing the MoUs with the DRC and Zambia, it had already signed six strategic partnerships on critical minerals with six different countries: Canada (June 2021), Ukraine (July 2021), Kazakhstan and Namibia (November 2022), Argentina (June 2023), and Chile (July 2023).

The signing of these agreements with the DRC and Zambia is largely due to the vast mining potential of both countries. The DRC is the world's leading producer of cobalt, accounting for 70% of global production, and the world's second-largest producer of copper. It is also the world's leading producer of coltan and is rich in lithium, nickel, and rare earth elements. Zambia, Africa's second-largest copper producer and the world's eighth-largest, also has reserves of cobalt, nickel, and manganese.

With the two countries, the preambles of the MoUs reaffirm among other things the EU’s need to secure and diversify its supply of CRM.

These agreements cover five areas of cooperation:7

- Integration of sustainable CRM value chains, including networking and joint development of projects.

- Mobilization of funding for the development of infrastructure required for the development of CRM value chains.

- Cooperation to achieve sustainable and responsible production and sourcing of CRMs.

- Cooperation on research and innovation and sharing of knowledge and technologies related to sustainable exploration, extraction, processing, and recycling of CRMs.

- Building of capacity to enforce relevant rules, increasing training and skills development related to the CRM value chain.

The agreement signed with Zambia and the DRC follows the signing of a series of agreements between these two countries between April 2022 and March 2023, concerning the development of a local value chain for electric vehicle batteries.

The DRC and Zambia’s Critical Raw Materials initiatives

In December 2022, at the US-Africa Leadership Summit in Washington, the US joined the two countries by signing a trilateral MoU concerning support for the Development of a Value Chain in the Electric Vehicle Battery Sector and aims “to facilitate the development of an integrated value chain for the production of electric vehicle (EV) batteries in the DRC and Zambia.”8

A year later after its signature, for unspecified reasons, the MoU has not materialized into a binding concrete agreement between the three countries.

On the DRC-Zambia side, they signed an agreement in March 2023 with the African Export-Import Bank (Afreximbank) and the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA) on Special Economic Zones (SEZ) to produce Battery Electric Vehicles. A pre-feasibility study was commissioned to be carried out by ARISE Integrate Industrial Platform (ARISE IIP).

In September 2023, the DRC minister of Industry, Julien Paluku, announced during a meeting in New York that the preliminary results of the study estimated the cost of building the SEZ between the two countries would be $30 billion US. Details about the funding and the next phases have not been made public so far.

The EU-DRC and EU-Zambia agreements are the latest developments on the subject in both countries.

Will the EU succeed where the US seems to be failing for now? The MoU states that the parties have six months from the date of signature to come up with a roadmap that will identify and determine the concrete actions to take to implement the agreements.

At the halfway point, the parties have until April 2024 to come up with the roadmap. If the deadlines are not met, the MoUs do not indicate what will happen. Will they be automatically renewed, or will they be considered null and void? It is worth remembering that these MoUs are in no way binding on the parties.

In the meantime, the viability of these MoUs and agreements to come will depend on all the parties’ ability to overcome the challenges of doing business in countries like the DRC and Zambia. The upcoming roadmap will have to address a wide range of domestic and external challenges that may hinder the implementation of the MoUs and the potential upcoming agreements. The US's difficulty in turning its December 2022 MoU into a concrete plan is a case in point.

Challenges

Agenda and priorities alignment

How will the EU, the DRC, and Zambia align their agendas?

On one side, though the EU’s approach toward the DRC and Zambia might be different from the US, they both seek the same overall goals and are both driven by national security concerns. Their need to secure their own, safe supply chain of critical minerals is driven by the necessity to reduce their vulnerability toward a geopolitical adversary. Their agenda is rather of a geopolitical and geostrategic nature than an economic one: a somewhat zero-sum approach.

On the other side, the DRC and Zambia’s demand for a local value chain of critical minerals is driven by industrialization and their socioeconomic development needs. On multiple occasions in the past, like many Global South countries, they have expressed their willingness to stay away from any global geopolitical conflict.

Despite the many problems associated with China's presence and engagements in their countries – e.g., mining investments in the DRC and Zambia's debt crisis - the two countries have never expressed any desire to distance themselves from Beijing. To the contrary, they have taken the opposite way.

In May 2023, during the DRC’s president Felix Tshisekedi’s trip to China, both countries upgraded their diplomatic relations to a “comprehensive strategic cooperative partnership,” the highest level of China’s diplomacy.

Although the DRC has embarked on a diversification of its mining portfolio, encouraging the presence of new countries such as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, China remains a key player in the Congolese mining sector. During the trip to Beijing, the Congolese authorities expressed their wish to see China's CMOC, owner and operator of the Tenke Fungurume mine – the world's largest cobalt mine – get involved in nickel exploration in the country.

Zambia, despite facing a debt crisis in which some degree of China's responsibility has been established, is nonetheless willing to use more Chinese renminbi in its transactions with China. China Civil Engineering Construction Corporation (CCECC), a subsidiary of China Railway, is also working on securing a billion-dollar deal for the concession of the TAZARA (Tanzania-Zambia Railway).9

In neither country is China’s influence and presence waning. Neither are these countries’ plans to develop a local value chain for critical minerals a zero-sum game. In other words, the DRC and Zambia are happy to work with whoever is able to support such plans.

Thus, the question becomes how the DRC, Zambia, and the EU are going to align their interests, and thus their approach and priorities, in implementing their MoUs. Are geopolitical considerations going to trample industrial, economic, and financial evidence? Or will the EU consider the possibility of working directly or indirectly with Chinese interests in both countries?

Alignment of agendas will certainly be the priority, as it will allow the parties to agree on contractual terms that truly meet their needs.

The EU and US agenda alignment in the DRC and Zambia

Besides aligning with Zambia and the DRC, the EU will have to consider the US agenda in these two countries, especially if the trilateral MoU also takes shape. Will the US and EU merge their agenda and cooperate? Or will they compete?

We should also point out that the current US initiative, the Mineral Security Partnership (MSP), which “aims to accelerate the development of diverse and sustainable critical energy minerals supply chains”10 counts several EU countries among its members including France, Germany, Finland, Norway, and Sweden, as well as the EU itself. This overlapping of players and initiatives raises the question of coordination and alignment of agendas and priorities.

As we can see, agenda alignment is a multifaceted and complex issue. All stakeholders need to address this effectively if they intend to set a framework that guarantees that both Zambia and the DRC are provided with the optimal solution to get their critical mineral local value chain.

The DRC and Zambia’s lack of Critical Raw Materials policies

While the EU and several countries have adopted regulations and policies, and have established their list of CRMs, many producing countries in the Global South such as Zambia and the DRC have yet to do so. The current understanding of CRMs in these countries is determined by the current demands for the minerals they host.

So far, only the DRC, following the amendment of its mining code in 2018, has issued a decree classifying cobalt, coltan, and germanium as strategic minerals.11 This was accomplished in November 2018. This was not part of an overall strategic minerals policy. The motivation was financial: The new 2018 mining code introduces a 10% royalty on minerals considered strategic by the Congolese government. In 2018, the price of cobalt had reached its peak of $95,250 US per metric ton, so the Congolese government was keen to make the most of this bonanza on the international market. The same was true for Germanium, which traded at $1084 US for Germanium dioxide and $1543 US/Kg for Germanium metal. Finally, for coltan, its historically high and constant demand by the electronics industry justified its classification.12 Since then, no comprehensive policy or strategic policy on CRMs has been adopted in the DRC.

As for Zambia, it was only in November 2022 that the government launched the 2022 National Mineral Resource Development Policy (MRDP) to improve the governance of the mining sector. The policy aims to address the challenges and gaps that were not resolved by the Mineral Resources Development Policy of 2013, such as inefficiencies in mining rights administration, environmental and social issues, lack of value addition, and low inclusivity of women and other vulnerable groups in the mining sector.

So, besides these broad general policies and regulations, both countries have yet to come up with a comprehensive strategic policy that determines and classifies their CRMs and sets their agenda and priorities on them. This is essential if they are to benefit from any form of collaboration with other partners and stakeholders.

In the case of the MoU with the EU, the document reads that “the partnership has the primary focus on strategic and critical raw materials as per the EU definition or its future updates,” a clarification that shows the extent to which the DRC and Zambia are likely to be working according to the EU's priorities and needs and not necessarily their own.

For instance, cooperation on cobalt, copper, nickel, lithium, and other EU strategic raw materials will only be possible as long as the EU considers them as CRMs.

The DRC and Zambia’s lack of strategic policies on CRMs reveals a lack of long-term vision and goals. This may translate into shortsighted and imbalanced agreements with the EU or any other partner.

The DRC and Zambia’s domestic challenges

The EU will also have to face challenges related to the political, social, and economic landscape and overall governance in the DRC and Zambia.

The DRC is emerging from a very tense electoral period, with the results of the presidential election disputed and rejected by the opposition. The Katanga region, where copper and cobalt are mined, is gripped by growing interethnic tensions that could lead to large-scale instability. In December 2023, before the election results were published, the central government reinforced the military presence in the region to ward off any armed unrest.

Political stability is central to the governance of the mining sector in the DRC. Political uncertainties, particularly those regarding the re-elected president's agenda and intention, tend to increase the country’s risk profile.

President Tshisekedi’s political future – will he abide by the constitutional limits or modify the constitution and seek a third term? – may affect his governance of the mining sector. As the EU is looking for a long-term partnership, the country's political stability for the next five to ten years becomes a key issue.

Beyond security and political stability, the governance of the mining sector itself is a major challenge. The opacity that is so characteristic of this sector, and the corruption that plagues it, make the DRC a high-risk country for western countries’13 private sector and investors.

In its 2022 Annual Survey of Mining Companies, which surveys mining and exploration companies about the mining investment landscape around the world, the Fraser Institute listed the DRC and Zambia among the bottom countries in terms of Investment Attractiveness Index14 and Policy Perception Index.15

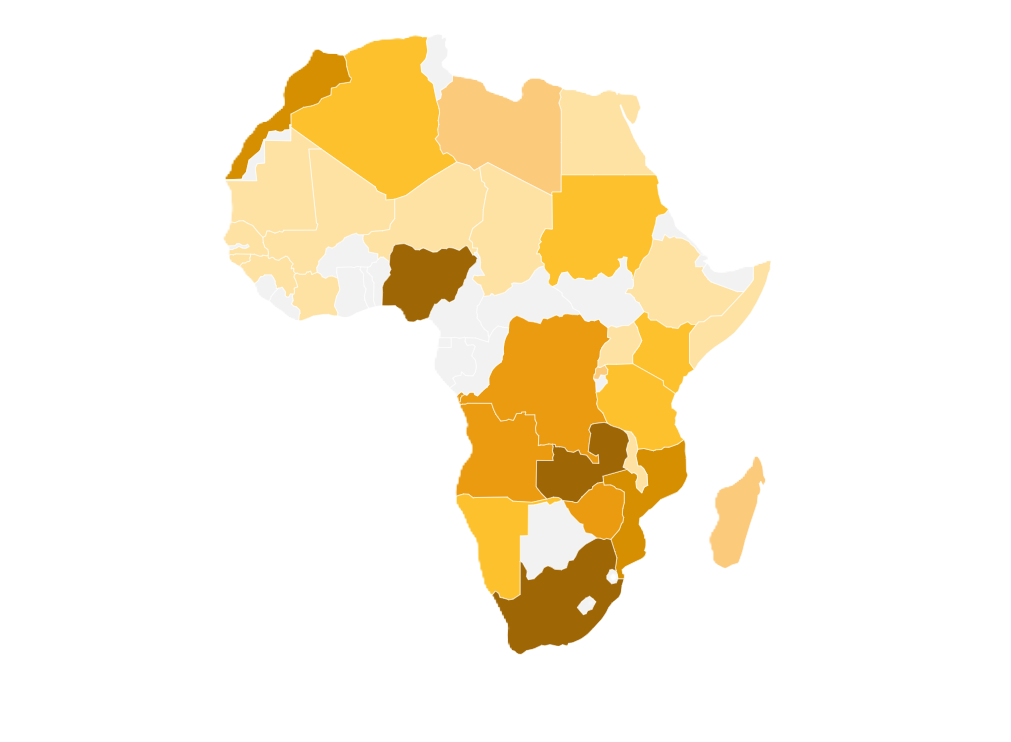

On its map of major EU suppliers of CRMs (2023) and their level of governance, the DRC is the only country listed with a very low level of governance. This alone is enough to deter the EU's private sector, a key player in the implementation of the EU strategy.

The challenge for the EU is how to incentivize European private companies to invest in such an environment with all the risks that may come with it.

The challenge of bad governance and corruption in the mining sector is also common in Zambia. During the critical raw materials session of the Global Gateway Forum in Brussels in October 2023, Zambia’s finance minister, Situmbeko Musokotwane, acknowledged the issue and the necessity for Zambia – and that can apply to the DRC as well – to de-risk its mining sector and create a conducive business environment.

The question becomes how the EU, the DRC, and Zambia intend to de-risk the mining sector for the EU’s private companies.

The EU’s challenges

EU private sector mobilization

As a result of the DRC and Zambia’s domestic challenges, the EU’s ability to mobilize, engage, and involve its private sector becomes another challenge for this partnership. The EU will have to provide strong incentives for private companies to join Brussels in its strategy in the DRC and Zambia.

Both the DRC and Zambia are aware of these limitations. Situmbeko Musokotwane acknowledged the EU’s difficulty to compel any private company to follow its priorities.

The solution would be for the three parties to de-risk mining investments and the business environment for the private sector. Since most of the risks are structural governance issues, a long-term solution would require a drawn out and tedious political process of strengthening good governance in these countries.

However, since the EU is not engaged in a state-building process with Zambia and the DRC, the real challenge then becomes how to engage with these countries despite the risks they represent, while complying with EU standards and international norms on mining investments and good practice.

If structural solutions are not forthcoming, risk mitigation and reduction could be achieved through new types of contracts and partnerships that address the complexities of governance in these countries. Innovative mechanisms that address the wide range of risks in these countries might provide certain guarantees for the private sector.

Securing the full support, participation, and alignment of the European private sector will be crucial to the EU’s efforts to build an alternative, China-independent CRM supply chain.

EU private sector relations with China

The EU's challenge with private companies is twofold. Beyond convincing private companies to invest in risky countries like the DRC or Zambia, convincing them to halt or considerably slow down engagement with Chinese companies in the critical minerals sector seems just as difficult.

The difficulty is tangible when we see how many private European companies continue to make deals, at various stages of the supply chain, with Chinese companies. Last year, for example, the French ERAMET and the German BASF were pursuing lithium deals with Chinese companies in Latin America.1617

Without the full participation of the private sector, the likelihood for the EU to succeed is quite low. One of Beijing's considerable advantages over its rivals is its ability to get the private and public sectors to align with its geopolitical and strategic objectives and become central to its strategy.

The EU’s competition with China will also play out in the DRC and Zambia. However, considering China's dominance of the Congolese and Zambian mining sectors, the willingness of the Congolese and Zambians to continue working with China, and finally China's dominance of other segments of the CRM supply chain, it’s clear that what is most at stake is the optimal approach the DRC and Zambia might take to achieve their own objectives.

Conclusions

The obstacles to achieving these agreements between the EU, Zambia, and the DRC are huge and complex. Geopolitical considerations and national security agendas, framed in a renewed cold war zero-sum mindset, reduce the options available to all the parties.

Beyond the aforementioned domestic risks, the real challenge for the DRC and Zambia and the prerequisite for any successful engagement in CRM supply chains will be to devise comprehensive and coherent national policies on strategic minerals – policies that set out the criteria for classifying strategic minerals, and the short-, medium- and long-term economic, industrial, and geopolitical objectives they wish to achieve. Without a long-term plan and vision, any engagement with a third party is likely to serve that party’s interests first and fail the DRC and Zambia in the long run.

For the EU, an economic and industrial agenda will have to take precedence over the security agenda, not only to meet Congolese and Zambian industrial objectives but also to create opportunities for trilateral cooperation with Chinese companies. The EU private sector engagements with Chinese companies show that CRM access is not a zero-sum game.

Since the energy transition is an existential global challenge, the world should de-politicize the question of access to the resources needed for its success.

However, if China remains the absolute red line for the EU, and if private European companies can't be persuaded to invest in the DRC and Zambia, strengthening the capacities of state-owned companies could be a solution in the medium term. The discovery and development of new deposits by Gécamines or Sakima in the DRC, or ZCCM Investments Holdings in Zambia, will help the EU to secure a direct supply of critical minerals through long-term supply agreements with these state-owned companies.

The difficulty that the EU and the US have in competing with China in countries like the DRC and Zambia is partly because they do not possess state-owned mining companies that can be used as geopolitical tools. In addition, poor governance in these countries, coupled with liberalism in the mining sector, allow Chinese companies, which are shielded from reputational damage, to adapt and thrive in these environments.

By strengthening the capacities of state-owned companies, which hold a large proportion of mining rights, the EU makes them reliable partners for the EU itself.

For economies reluctant to have their own state-owned mining companies and the risk of monopoly they may represent, the strengthening of state-owned companies in producing countries could be the next viable option. This approach becomes particularly relevant when facing with an adversary that not only possesses the necessary economic tools, but is also not bound by the principles that prevent Western private companies from accessing risky but strategic countries.

Endnotes

1European Commission: “Study on the Critical Raw Materials for the EU 2023”: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/57318397-fdd4-11ed-a05c-01aa75ed71a1

2European Commission Press Release on March 16th, 2023 : “Critical Raw Materials: ensuring secure and sustainable supply chains for EU's green and digital future” : https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_23_1661

3Id

4Id

5Id

6European Commission Press Release on March 16th, 2023: “Critical Raw Materials: ensuring secure and sustainable supply chains for EU's green and digital future” : https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_23_1661

7Extracted and shortened from the “Memorandum of Understanding on a Partnership on sustainable raw materials value chains BETWEEN the European Union represented by the European Commission and the Republic of Zambia”: https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/publications/memorandum-understanding-eu-zambia-sustainable-raw-materials_en?prefLang=de

8US Department of State: “Memorandum of Understanding among the United States of America, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and the Republic of Zambia concerning support for the development of a value chain in the electric vehicle battery sector.” : https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/2023.01.13-E-4-Release-MOU-USA-DRC-ZAMBIA-Tripartite-Agreement-Tab-1-MOU-for-U.S.-Assistance-to-Support-DRC-Zambia-EV-Value-Chain-Cooperation-Instrument.pdf

9The TAZARA is 1860 km railway financed and built by China 1975 that connect Kapiri-Mposhi in Zambia to the port of Dar-Es-Salam in Tanzania. Zambia, Tanzania, and China are currently working on deal for its refurbishment and concession by China Civil Engineering Construction Corporation.

10US Department of States: “Minerals Security Partnership” : https://www.state.gov/minerals-security-partnership/

11On November 24, 2018, the Congolese prime minister signed decree number 18/042 regarding strategic mineral substances in the DRC : https://congomines.org/reports/1609-decret-portant-declaration-des-substances-minerales-strategiques-en-rdc

12Bokundu Mukuli G. & Cihunda Joseph “Réflexions sur la Régulation et le Contrôle des Minerais Stratégiques d’ Exploitation Artisanale en République Démocratique du Congo” Southern Africa Resources Watch (SARW), July 2020: https://congomines.org/system/attachments/assets/000/001/954/original/Réflexions_sur_la_Régulation_et_le_Contrôle_des_Minerais_Stratégiques_d_Exploitation_Artisanale_en_République_Démocratique_du_Congo_v12_%281%29.pdf?1596708109#:~:text=La%20République%20Démocratique%20du%20Congo,la%20mitigation%20du%20changement%20climatique.

13The DRC has a score of 7 on the OCDE Country Classification: https://www.oecd.org/trade/topics/export-credits/arrangement-and-sector-understandings/financing-terms-and-conditions/country-risk-classification/

14The Fraser Institute Survey defines as “The Policy Perception Index, a composite index that measures the effects of government policy on attitudes toward exploration investment.” Julio Mejía and Elmira Aliakbari: Fraser Institute Annual Survey of Mining Companies 2022: https://www.fraserinstitute.org/sites/default/files/annual-survey-of-mining-companies-2022-execsum.pdf

15“Policy factors examined include uncertainty concerning the administration of current regulations, environmental regulations, regulatory duplication, the legal system and taxation regime, uncertainty concerning protected areas and disputed land claims, infrastructure, socioeconomic and community development conditions, trade barriers, political stability, labor regulations, quality of the geological database, security, and labor and skills availability.” Julio Mejía and Elmira Aliakbari: Fraser Institute Annual Survey of Mining Companies 2022: https://www.fraserinstitute.org/sites/default/files/annual-survey-of-mining-companies-2022-execsum.pdf

16The German chemical company BASF is considering to build a lithium processing plant in Chile in collaboration with Chinese BYD Co. and Tsingshan Holding Group. “Germany’s BASF considers building lithium plant in Chile” : https://www.mining.com/web/germanys-basf-considers-building-lithium-plant-in-chile/

17The French lithium company Eramet is pursuing a lithium project in Argentina in joint-venture with China’s Tsingshan Holding group: “ Eramet rues timid European banks, sees lithium plant costing $1.5 billion” : https://www.mining.com/web/eramet-rues-timid-european-banks-sees-lithium-plant-costing-1-5-billion/

About the Author

Christian Géraud Neema

Christian Géraud Neema Byamungu is an analyst, observer, and researcher of China-Africa relations. He researches natural resources revenue management in non-democratic resource-rich countries and geopolitics of natural resources and is currently the Africa editor of the China-Global South Project, a multimedia project that covers China's engagement in the global south. He is a graduate of Renmin University of China and holds a master's degree in international development from the International University of Japan.