Executive Summary

Download summaryMapping Africa’s Green Mineral Partnerships delves into the evolving landscape of bi- and multilateral agreements between African states and global powers concerning access to “critical” or “green” minerals. The sector has been a global focal point not only because of the exponential rise in demand driven by the global green energy and digital transitions, but also because of security concerns arising from shifting geopolitical tensions, supply chain disruptions, and the concentration of refining capabilities in China. Against this backdrop, Africa’s rich mineral endowment has drawn considerable attention. Various bilateral agreements – ranging from strategic partnerships to cooperation agreements – have been established with African states to secure mineral access, promote joint ventures, and integrate mineral value chains.

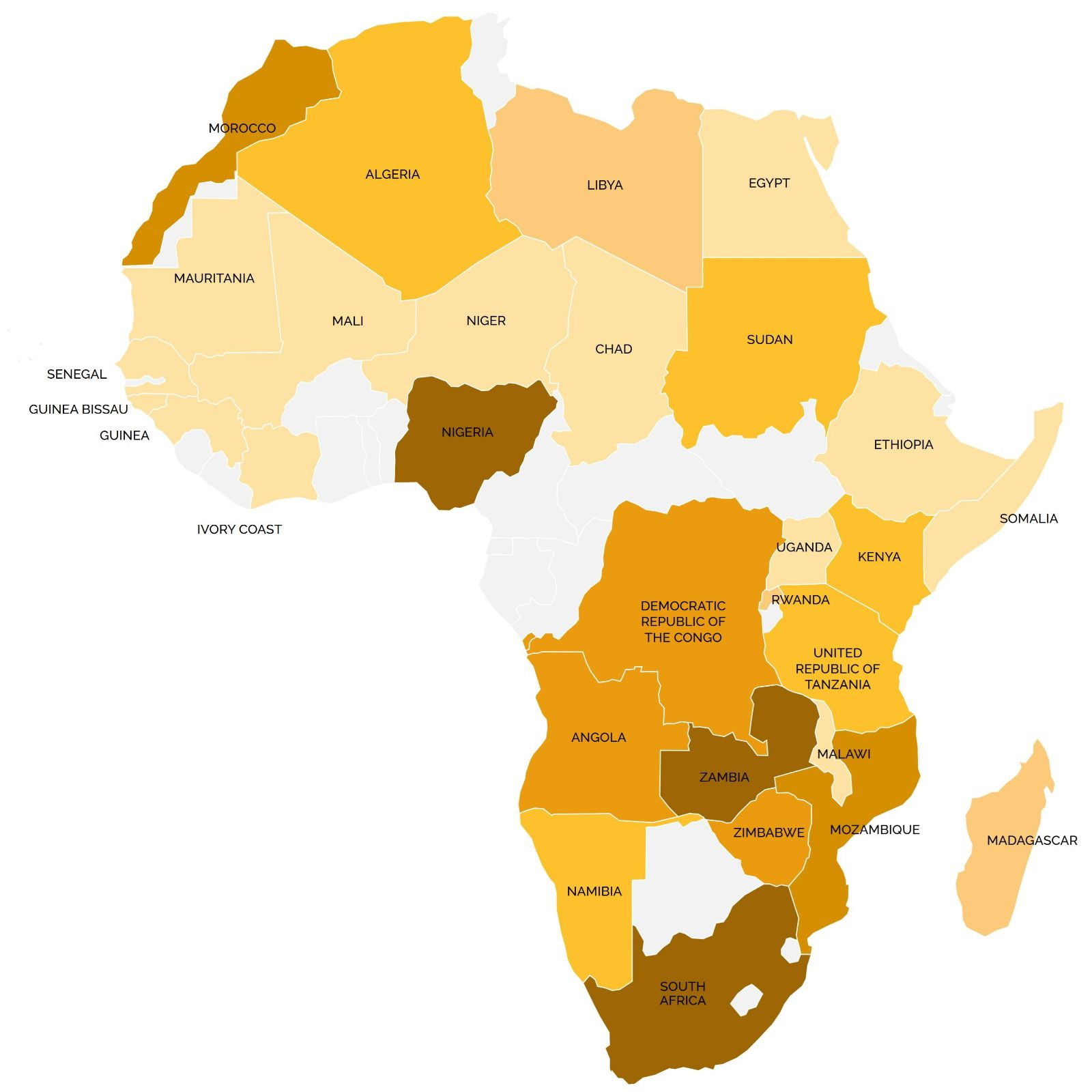

Despite their importance, these agreements are often opaque, with limited public accessibility to allow for comparative analyses. In order to obtain a more comprehensive view of Africa’s green mineral partnerships, APRI conducted an extensive online search using multiple search engines and databases. The search was scoped to include G20 and BRICS+ member states, and states with a strong mining sector, such as Chile, Cuba and Venezuela. The collected data is depicted in an interactive online map, which includes nearly one hundred agreements, and offers insights into their content, initiation date, and public accessibility.

This report provides an in-depth analysis of twelve prominent global actors who have such partnerships with African states. These are: the United Kingdom, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Russia, India, China, South Korea, Japan, Indonesia, the United States, the European Union. Each country and the EU section includes:

- Key findings

- An overview of the national minerals strategy and geopolitical ambitions.

- Examination of relationships and agreements with African states.

- Discussion of additional measures beyond bilateral agreements.

Our investigation of these agreements has yielded several key insights into the evolving dynamics of resource diplomacy and the governance of critical mineral extraction. Firstly, the analysis underscores the prominent roles of global actors like China and Russia, in contrast with the relative scarcity of agreements involving traditional mining powers such as Australia and Canada.

Secondly, the nature of these agreements varies significantly, with some emphasizing direct state cooperation and the allocation of state funds, while others focus on fostering an enabling environment for private sector investment – a strategy that may lead to slower tangible results. Some agreements prioritize the inclusion of social and environmental standards, while others omit these considerations. The former approach, though potentially resulting in slower project execution, reflects the principled stance of the initiating countries. In this way, agreements frequently mirror broader geopolitical, historical, and power-related considerations, with countries selecting partners based on strategic factors such as trade terms, historical allegiances, and cross-sector cooperation.

The analysis also reveals the realpolitik of critical mineral extraction in Africa. Countries are increasingly viewing their critical mineral supply chains not just in terms of global competitiveness or even global responsibility to decarbonise, but as an issue affecting national security. The urgency with which critical minerals are pursued raises important questions about how it will affect Africa’s agency in governing the extraction of these resources in the future.

Finally, the report underscores the need for greater transparency and accessibility in these agreements to better understand their implications and foster informed public discourse. Despite the strategic importance of these agreements, many remain vague and non-binding, necessitating further levers such as preferential financing to stimulate private investment. This transparency is crucial not only for economic clarity but also from public, democratic, and human rights perspectives, ensuring that these agreements align with broader societal interests.

Introduction

With rising geopolitical tensions, global supply chain disruptions and the projected exponential rise in demand for so-called “critical minerals” (Dikau et al., 2023) required for the ongoing global green energy and digital transitions, countries worldwide are increasingly prioritizing stable future supply of mineral inputs. This shift has led to a growing number of multilateral, bilateral or state-to-state agreements aimed at boosting production, securing access to critical minerals and countering other countries’ dominance in critical mineral supply chains. Sometimes referred to as ‘mineral partnership,’ ‘memorandum of understanding’ (MoU), ‘strategic partnership,’ ‘cooperation agreement’ or ‘ joint statement of cooperation,’ these agreements contain a wide range of provisions, including mineral value chain integration, promotion of joint business ventures and investments, knowledge sharing and capacity building in the minerals sector

Africa’s rich endowment of critical minerals has sparked interest in importing countries.

Africa’s rich endowment of critical minerals has sparked interest in importing countries. Consequently, African states are increasingly entering such bilateral agreements (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, 2024). As depicted on APRI’s interactive map, countries such as South Africa, Zambia and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) have each committed to at least six such agreements. Despite the importance of these agreements in shaping the future of African critical minerals governance, information about them - their content, intent, and even their very existence - is not always accessible to the public and rarely provides a comparative perspective on these partnerships (Agora Strategy Group, 2023; International Energy Agency [IEA], 2021).

The report aims to provide a more comprehensive overview of green, also referred to as ‘critical,’ mineral agreements made with African states.

The report aims to provide a more comprehensive overview of green, also referred to as ‘critical,’ mineral agreements made with African states. The report is best utilized with APRI’s interactive map, which illustrates the various types of agreements and participating states mentioned herein. Additionally, the report focuses on a selection of countries considered the most active in the African green minerals landscape. Specifically, the report examines the strategies employed by non-African actors in securing mineral agreements with African countries, exploring how global powers navigate Africa’s green minerals landscape. It is important to note, however, that while the scope centers on external actors, African countries are not passive participants in these partnerships. On the contrary, many African leaders actively shape these agreements, selectively engaging with offers and strategically rejecting certain initiatives in favor of others that better align with their national and regional interests.1

Between 2019 and 2023, 43 national critical minerals strategies on critical minerals were adopted worldwide.

The bilateral agreements discussed here are typically preceded and informed by a country’s domestic national minerals strategy and vary substantially in their objectives, key stakeholders and format. Between 2019 and 2023, 43 national critical minerals strategies on critical minerals were adopted worldwide (International Renewable Energy Agency, 2023). These documents often outline which minerals are critical to that country’s economic goals, energy security, or other reasons, such as digitization ambitions. As a result, the minerals deemed ‘critical’ are context-specific. Domestic strategies are sometimes accompanied by establishing multilateral partnerships or hosting mineral forums, which connect governments, investors and companies (United States Department of State [US DOS], 2022; Future Minerals Forum, 2024). Numerous partnerships have also been established between mining research institutions worldwide (Japanese Organization for Metals and Energy Security [JOGMEC], 2023).

In some contexts, investments by state-owned enterprises are encouraged, with representatives accompanying state visits to mineral-supplying countries (Metsel, 2019). In others, private sector actors are expected to take the lead, bolstered by bilateral investment treaties or incentives such as the European Union’s (EU) “de-risking” strategy (Findeisen & Wernert, 2023). Even so, the high levels of risk associated with extractive projects – coupled with their time-consuming and capital-intensive nature – continue to constrain the volume of investment that Africa and its geopolitical partners seek (Hruby, 2024). For example, the EU’s strategic partnership with Namibia has not significantly stimulated European investment in the country’s critical mineral sector despite Namibia’s favorable political stability and investment environment (Logan, 2024). As such, the actual level of financial commitment by corporate actors is often influenced by the nature of diplomatic relationships. In particular, alignment between a state’s broader policies and its agreements with African states significantly shapes the risk profile of extractive projects. Perceived risk is also influenced by the type of investors, whether public or private. For instance, investors from China or the Gulf may be less deterred by short-term risks and more inclined to pursue longer-term strategic objectives (Njini & Denina, 2024).

As such, the actual level of financial commitment by corporate actors is often influenced by the nature of diplomatic relationships.

The drivers behind the adoption of state-to-state agreements inherently vary among participating actors. Buying countries typically seek diversified and long-term access to critical minerals at competitive market prices. Conversely, supplier countries seek to capture a greater share of the proceeds from mineral extraction, for example, by including local content provisions or requiring investments in future processing facilities (World Economic Forum, 2024). The latter approach was once emphasized by Nigeria’s Minister of Solid Minerals Development, Henry Dele Alake, who has stated his aim to “transform Nigeria’s wealth into industrial and economic power... in ways that ripple through our economy” (quoted in Lawal, 2024; Anyanwu, 2024).

Other countries may position themselves as key intermediaries between supplier and buyer countries, taking advantage of their geographical position (World Economic Forum, 2024). Saudi Arabia, for instance, aspires to become a “hub of innovation and responsible production” (Future Minerals Forum, 2024b) within the minerals “super-region” of Africa, the Middle East and Central and South Asia (Varriale, 2024).

One common feature of these state-to-state mineral agreements is their limited transparency and public accessibility.

One common feature of these state-to-state mineral agreements is their limited transparency and public accessibility. The publicly available agreements – such as those made by the EU, India, Indonesia and the United States (US) – often contain vague and cryptic provisions. Typically signed during state visits or international forums, understanding their significance often requires piecing together information from news articles, ministry reports and interviews. Furthermore, many agreements are not legally binding and have a predetermined validity period, after which they either expire or require revision.

This lack of transparency means that the specific provisions of agreements are often difficult to ascertain. Where publicly available information or analysis exists, it becomes clear that the conditions and scope of agreements vary considerably between the countries involved. Some serve as an initial platform for future cooperation on mineral supply chains (Fitzgerald et al., 2024). For example, some agreements contain specific provisions to establish a joint minerals committee that meets regularly and formulates future agreements (Anyanwu, 2024). The EU’s agreements typically include provisions for establishing a joint roadmap to steer future cooperation and emphasize partnerships between producer and consumer countries (European Commission, & Republic of Namibia, 2022; Vandome, 2023). Some agreements serve a more tangible geopolitical agenda and seek to expand the parties’ alliances and enhance their geopolitical influence. In its efforts to form an alliance against the West, Russia, for instance, offers supplier countries its mining expertise in conjunction with a range of other services, including security services (Vidal, 2023).

Despite the widespread use of vague language in these agreements, tacit support can help ensure that the agreement’s goals are met. For example, a common goal stimulating private investment from the buyer country. Some analysts are doubtful whether state-to-state agreements on their own can lead to the type of investments envisioned by such agreements. Most partnerships will need to rely on levers like preferential financing and development assistance to attract private investment (Fitzgerald et al., 2024). However, strengthened geopolitical relations and investment interests may be mutually reinforcing. For example, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) signed an agreement with Zambia in July 2023 (Lusaka Times, 2023). Later that year, in December 2023, Abu Dhabi’s International Resources Holding (IRH) won a USD 1.1 billion (EUR 1.05 billion) bid to become the new strategic equity partner of the state firm Zambia Consolidated Copper Mines Limited in Mopani Copper Mine, outmaneuvering the South African firm Sibanye-Stillwater and China’s Zijin Mining Group (Mining MX, 2023). IRH’s substantial financial commitment will no doubt fortify the UAE and Zambia’s geopolitical relationship, which may, in turn, stimulate further private investment. This phenomenon can also be observed with Turkey’s signing of a bilateral agreement with Niger in 2017 that included cooperation on geological and mineral exploration. In September 2020, Turkey’s MTA International Mining Inc. began exploration activities in Niger (MTAIC Niger Mining Limited, n.d.).

“Despite the widespread use of vague language in these agreements, tacit support can help ensure that the agreement’s goals are met.

Regardless of their contents, these bilateral agreements reflect the contemporary geopolitical landscape. The rapidly increasing demand for green minerals and states’ involvement in negotiating the terms of extraction has resulted in intense competition, compounding the unpredictability of already volatile supply chains. As countries seek to secure access to critical minerals, their approaches are often misaligned and contradictory, even between countries with well-established working relationships, such as the EU and the US. This misalignment might spark frictions that could impact international cooperation in the sector. For example, while the EU and the US share concerns about critical raw material (CRM) supply and processing capacity, their domestic priorities conflict with broader geostrategic objectives. Furthermore, the uneven spatial distribution of reserves and bottlenecks in processing CRMs result in geographically concentrated supply chains and an overreliance on specific suppliers. This liability explains countries’ urgency to diversify supply chains and partnerships to enhance economic security (Agora Strategy Group, 2023).

Some agreements serve a more tangible geopolitical agenda and seek to expand the parties’ alliances and enhance their geopolitical influence.

Governments select bilateral partners based on several strategic factors – including favorable terms of trade. However, previous allegiances and the depth of cooperation in other sectors also play a pivotal role when making such decisions. For example, the United Kingdom (UK) has established partnerships with Nigeria, South Africa and Zambia – all existing members of the Commonwealth. Similarly, Russia’s partnerships today reflect its historical relationships. During the Cold War, the Soviet Union supported the independence movements of Angola and Mozambique while also funding South Africa’s African National Congress (in the fight against apartheid (Al Jazeera, 2023; Droin & Dolbaia, 2023). Today, Russia has official partnerships with these three countries. Turkey’s partnerships in Eastern and Western Africa overlap with its expanded security and military cooperation in both regions. Thus, establishing mineral partnerships is closely linked to broader geopolitical, historical and power-related considerations (Donelli, 2022).

Governments select bilateral partners based on several strategic factors – including favorable terms of trade.

Methodology

This report discusses the most salient bilateral agreements in the minerals sector between African and non-African states (see Figure x). The discussion below and APRI’s accompanying interactive map detail the 11 partners (including the EU2) involved in these agreements, as well as additional information on the date of each agreement, its content and a link to the document, where available.

APRI conducted an extensive online search using multiple search engines and databases to gather this information.3 The search was scoped to include G20 and BRICS+ member states, and states with a strong mining sector, such as Chile, Cuba and Venezuela (Hache & Roche, 2024).

Although the search has yielded a significant number of partnerships, the collection cannot be considered exhaustive.4 Therefore, the information will need to be regularly updated. Nevertheless, the existing database contains nearly one hundred agreements. Its value lies in its inclusion of agreements that were only brought to attention through news agency reports, in addition to those published by governments.

The search yielded details of partnerships for countries that are prominently featured in green minerals-related literature, such as China, Russia and Saudi Arabia. However, it is noteworthy that partnerships were also identified for actors that feature less prominently in the green minerals debate, including India, Indonesia and Turkey. The search yielded surprisingly few results for some established mining powers, such as Australia, Brazil and Canada. Therefore, these countries will not be elaborated on in this report.

Each country discussion is organized as follows:

- First, the country’s national minerals strategy is outlined alongside its geopolitical ambitions.

- Then, its relationships and agreements with African states are explored.

- Finally, any measures beyond bilateral agreements are discussed.

The actors are clustered geographically, beginning with the UK, then the Middle East, Russia, Asia, North America and the EU.

United Kingdom

- Driven by geopolitical competition and a need to secure supply chains for key technologies, the UK’s approach to critical minerals has evolved from a broad focus on collaboration in 2022 to a more targeted strategy in 2023. The renewed strategy prioritizes domestic production and strategic partnerships with resource-rich nations.

- Leveraging its relationships within the Commonwealth and its longstanding presence in the African mining sector, the UK is actively forging partnerships with nations like South Africa, Nigeria and Zambia. Partnerships promote responsible sourcing, investment and knowledge exchange to ensure access to critical minerals.

- The UK is also investing heavily in research and development, both domestically and in developing countries, to drive innovation in extraction, processing and recycling. This includes initiatives like the Circular Critical Materials Supply Chains program.

The UK has a long history of engagement in the mining sector, with numerous globally operating mining companies. In 2022, the UK government published its first strategy paper for critical minerals, entitled "Resilience for the Future: The United Kingdom's Critical Minerals Strategy” (UK Government, 2022a), which was updated in 2023 with the new title “Critical Minerals Refresh: Delivering Resilience in a Changing Global Environment” (UK Government, 2023). The latter outlines the UK’s strategic adjustments to ensure supply chain resilience in response to evolving geopolitical and global challenges. It emphasizes progress in implementing the original strategy, strengthens international partnerships and aims to deepen collaboration through international frameworks. The strategy aims to ensure a stable supply of minerals for the production of clean energy technologies, cutting-edge military technology and electronics. It envisions the UK actively working to secure its supply of essential minerals by strengthening its economic resilience and competitive edge in the global market (Holman Fenwick Willan, 2024).

The document indicates that the UK aims to regain its status as a leader in the critical minerals sector by maximizing production across the value chain – from mining and refining to manufacturing and recycling – in a way that fosters innovation and creates jobs. The stated intention is to support the UK's ambitions for the net zero transition, energy security and becoming a global scientific leader (UK Government, 2022a). While the Critical Minerals Refresh maintains this narrative, it places greater emphasis on the geopolitical competition for critical minerals. It introduces an independent “Task and Finish Group”, to support key manufacturers in improving their supply chain resilience (William & Arkell, 2023). The refreshed strategy has also launched several initiatives to support innovation and supply chain development. These include the Circular Critical Materials Supply Chains program, a £15 million fund dedicated to domestic research and the £65.5 million Accelerate-to-Demonstrate Facility under the Ayrton Fund, which promotes critical mineral technology advancements in developing countries (UK Government, 2023).

The stated intention is to support the UK’s ambitions for the net zero transition, energy security and becoming a global scientific leader.

The 2022 strategy furthermore highlights the importance of international collaboration, positioning it as one of three central pillars alongside strengthening international markets and boosting domestic production. It emphasized collaboration broadly, while the 2023 refresh provided specific examples, including agreements with Canada and South Africa and active participation in international frameworks such as the Minerals Security Partnership (MSP), the IEA, and the G7 (UK Government, 2023).

Domestically, the UK plans to scale up efforts in exploration, financial support, capacity building, research and development and recycling, but it recognizes that complete self-sufficiency is “not possible (or even desirable)” (p. 12). Internationally, the UK aims to build partnerships with “influential countries and strategic producer countries” (p. 30), which has materialized in its membership in the US-led MSP (UK Government, 2022a).

In terms of bilateral partnerships with African states, Nigeria (Adebayo, 2024), Zambia (UK Government, 2023) and South Africa (Campbell, 2022), all members of the Commonwealth, have indicated their willingness to enter into an agreement with the UK. The agreement with Zambia is designed to increase trade volume and promote investments. In contrast, an extensive agreement with South Africa aims to promote responsible exploration, production and processing of minerals, as well as investments in these areas, including promoting joint ventures, vocational and technical education and exchanging experts (Campbell, 2022). Nigeria and the UK have established a joint technical working group to promote investments (Adebayo, 2024; UK Government, 2021, 2022b).

Beyond bilateral cooperation, it is worth noting that British companies have a significant presence in the African mining sector. For instance, the London-based company Anglo American – founded in South Africa in 1917 – is responsible for 14.9% (Soulé, 2024) of the output in the African mining sector, which includes the production of copper, manganese and platinum group metals (Anglo American, n.d.).

The UK’s has bilateral agreements with three African states.

Nigeria

Zambia

South Africa

View the UK’s partnerships on APRI’s interactive map.

Turkey

- In line with its 2017 National Energy and Mining Policy and 12th Development Plan (2024-2028), Turkey is pursuing a dual-track strategy to secure critical minerals for renewable energies by improving investments in its domestic mining sector and increasing partnerships with mineral-rich countries, particularly in Africa.

- Turkey has agreements with at least 17 African states in the energy and mining sectors, but only eight are publicly available. These agreements, concluded between 2016 and 2024, prioritize technical cooperation, capacity building, investment promotion and joint project development.

- Through initiatives like the Türkiye-Africa Business Forum and Turkish government-affiliated MTA International Mining Inc., Turkey is successfully expanding its integration into value chains across a number of African countries.

Turkey expressed a strong desire for national energy independence in its 2017 National Energy and Mining Policy, which aims to increase the share of renewable energies in its energy mix (Karagöl et al., 2017). The country’s 12th Development Plan (2024-2028) addresses the role of critical minerals more explicitly, outlining a principal objective of reducing dependence on imports and establishing supply security for certain minerals in the wake of the green and digital transitions (Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Strateji ve Bütçe Başkanlığı [Presidency of Strategy and Budget of the Republic of Türkiye], 2023a). In addition, a national critical minerals strategy was being developed at the time of publication.

Turkey also possesses a range of critical mineral reserves, such as tungsten, rare earth elements, cobalt and graphite, so it is considering a dual strategy for securing its supply (World Mining Congress, 2024). On the one hand, it plans to improve its national investment environment through institutional and legislative reforms. On the other, it plans to cooperate with mineral-rich countries and increase its investment and exploration efforts abroad (Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Strateji ve Bütçe Başkanlığı, 2023a).

Turkey’s traditional focus on the North and the Horn of Africa can be explained by its geographic proximity and longstanding religious ties.

The Turkish Minister for Energy and Natural Resources mentioned Turkey’s cooperation agreements with 17 African states in the energy and mining sectors; however, details of only eight of them can be found publicly (Daily Sabah, 2020). These agreements, regionally concentrated in Northern, Western, Eastern and the Horn of Africa, were concluded between 2016 and 2024. Turkey’s traditional focus on the North and the Horn of Africa can be explained by its geographic proximity and longstanding religious ties. At the same time, the recent outreach to Western Africa is driven by its ambition to deepen Africa-Turkey cross-regional commercial connectivity (Pinto, 2024; Tanchum, 2021).

As for the African continent, Turkey has a strong interest in value chain integration with African partners to expand its industrial base, given the continent's immense future economic growth trajectory (Tanchum, 2021). Reports indicate that the agreements focus on technical, legislative, scientific and administrative cooperation, capacity building, the promotion of investments, as well as joint project development. In the case of Ethiopia, Guinea, Niger and Sudan, the focus includes cooperation in geological exploration and mapping (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations [FAO], 2017a; 2017b; 2018; Nordic Monitor, 2020). One example of successful cooperation in mineral exploration is the activity of the Turkish government-affiliated MTA International Mining Inc., which conducts geological, geophysical and geochemical research to explore mineral reserves in Sudan and Niger (Republic of Turkey Ministry of Trade, n.d.).

In addition to bilateral cooperation, investments and joint ventures are fostered through the Türkiye-Africa Business Forum, which has been held regularly since 2016, although not with an exclusive focus on minerals (Turkey-Africa Business Forum, n.d.).

Turkey has bilateral agreements with eight African states.

Ethiopia

Guinea

Morocco

Niger

Nigeria

Uganda

Somalia

Sudan

View Turkey’s partnerships on APRI’s interactive map.

Saudi Arabia

- Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 identifies the critical minerals sector as a key pillar that supports its ambitions in renewable energy, digital infrastructure and defense.

- Saudi Arabia has forged strategic partnerships with at least eight African countries. These agreements promote investment, knowledge transfer and technical and legislative cooperation.

- Saudi Arabia is securing access to critical materials through several noteworthy efforts, such as the recent public-private bid for ownership of Zambia’s Sentinel and Kansanshi copper mines and the state’s prominent participation in the annual Future Minerals Forum.

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia's intensifying emphasis on the critical minerals sector is reflected in Vision 2030, a government program initiated in April 2016. Vision 2030 identifies the mineral sector as a key economic pillar for the future and a crucial element in the country's economic diversification beyond its traditional reliance on oil. The government has plans similar to those of many other governments worldwide, which include achieving carbon neutrality by 2060, increasing the share of renewable energy, developing a sophisticated digital infrastructure and localizing the defense industry (Alqarout, 2023). All these plans require substantial access to critical minerals. The desire to expand in these sectors further reflects the country's ambition to exert greater influence on the global stage and act as a representative of its region (Bianco, 2024). Saudi Arabia considers itself part of a “super region” of Africa, the Middle East and Asia (Varriale, 2024), and it strives to refine and process its natural resources to retain greater value. Leveraging its central position between the continents, Saudi Arabia envisions itself as the super region’s “hub” for innovation (Future Minerals Forum, n.d.).

One of the strategies included in Saudi Arabia's Vision 2030 is the establishment of strategic international partnerships, which explicitly extend to the mining sector. At least eight African countries have established mineral partnerships with Saudi Arabia, extending beyond the Kingdom’s traditional regional focus on the Horn of Africa and encompassing countries across the continent (Bianco, 2024). The agreements were established in 2023 and 2024 and include provisions for promoting investments and collaboration in the mining sector (Ross, 2024). The agreements with Chad, Senegal, Zimbabwe and Mauritania reportedly also include provisions on technical and legislative cooperation, knowledge and technology transfer and promoting partnerships between public, semi-public and private institutions (Saudi Gazette, 2024).

In January 2023, Manara Minerals was established as a joint venture between the state-owned mining company Ma'aden and the Kingdom's Public Investment Fund (n.d.). Manara Minerals may serve to follow up on investment commitments made in partnership agreements, as evidenced by its recent bidding on stakes in Zambian copper mines Sentinel and Kansanshi (Enterprise News, 2024). Additionally, Saudi Arabia's efforts are evident in the annual organization of the Future Minerals Forum, which brings together investors, governments and international organizations. This event saw the signing of numerous state-to-state partnerships in the previous year (Future Minerals Forum, n.d.).

Saudi Arabia has bilateral agreements with eight African states.

Chad

DR of Congo

Egypt

Mauritania

Morocco

Nigeria

Senegal

Zimbabwe

View Saudi Arabia’s partnerships on APRI’s interactive map.

United Arab Emirates

- To diversify its economy and gain a strategic edge, the UAE is securing critical minerals for green technologies and defense, leveraging its long-term outlook and capital reserves for higher-risk projects.

- The UAE’s strategy in Africa centers on investments by Emirati companies, exemplified by major acquisitions in Zambia and the DRC, alongside a $1 billion green metals investment in South Africa.

- Beyond mining, numerous bilateral investment treaties with African states provide a framework for UAE companies to simultaneously engage across various sectors, supporting its broader economic and geopolitical goals.

Competing with Saudi Arabia for regional leadership, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) is also expanding its critical mineral initiatives. Traditionally, the UAE's involvement has been concentrated in North and East Africa. However, since 2020, the UAE's economically driven agenda has inspired engagement with the entire African continent. Similar to Saudi Arabia, the UAE is seeking economic diversification to build a future-proof green economy with expanded digital infrastructure (Procopio & Čok, 2024). In addition, the UAE has a strong interest in defense and aims to gain a "strategic edge" over other regional competitors. To this end, it is pursuing the supply of so-called “dual-use minerals” (Jahn, 2024). The UAE’s long-term strategic outlook, underpinned by substantial capital reserves, enables it to undertake higher-risk projects that align with its geopolitical objectives (Njini & Denina, 2024).

APRI’s search for bilateral agreements has yielded two results: a 2023 MoU with Zambia on the exploration of mineral resources and a 2024 bilateral investment cooperation agreement on mining with Kenya (Lusaka Times, 2023; Sharma, 2024). The limited number of publicly available bilateral agreements between the UAE and African states does not indicate inactivity on the continent. Rather, its strategy appears to center on promoting mining investments by Emirati companies. In 2023 alone, International Resource Holdings, which forms part of the International Holding Company chaired by Sheikh Tahnoon bin Zayed al-Nahyan, acquired a 51% stake in Zambia's Mopani Copper Mines for $1.1 billion; the UAE government signed a $1.9 billion agreement with the DRC's state-owned mining company Sakima; and Abu Dhabi's F9 Capital Management signed a $1 billion green metals investment agreement in South Africa (Procopio & Čok, 2024). Additionally, the UAE’s ambitious investment strategy is reflected in the high number of bilateral investment treaties signed between the UAE and African states, which are more numerous and geographically dispersed than those of its Gulf neighbors (White & Case LLP, 2022).

The UAE has bilateral agreements with two African states.

Kenya

Zambia

View the UAE’s partnerships on APRI’s interactive map.

Russia

- Russia’s strategy in Africa aims to secure raw materials to generate financial stability amidst sanctions and to gain geopolitical leverage.

- Driven by its updated mineral resource strategy, Russia prioritizes reducing foreign dependence and expanding domestic production. The diversification of international supply chains is a secondary objective pursued through partnership agreements.

- Dating back to 1999, Russia’s bilateral agreements focus on technical cooperation and expertise sharing, often complemented by security provision in exchange for access to resources.

Russia's strategy for securing access to raw materials in Africa differs substantially from those of other actors and serves two main objectives: financial stability and greater global geopolitical leverage. More specifically, Russia’s strategy is to sell imported resources, including gold and diamonds, to generate liquidity in response to the international sanctions regime imposed against it (Vidal, 2023). Simultaneously, Russia leverages its mineral resource diplomacy to advance its broader strategic goals of reclaiming great power status, fostering a multipolar world order and forming an alliance against the West (Stronski, 2019).

In late July 2024, Russia announced an updated version of its mineral resource strategy. The strategy is driven by the anticipation of a considerable increase in its future mineral demand, largely due to elevated growth rates observed in the military industry, metallurgy, the chemical industry and the construction sector (Government of Russia, 2024). Given its considerable natural resource deposits of a range of critical minerals, Russia’s primary strategy is to reduce foreign supply dependence and expand domestic production. A secondary objective – the diversification of its international minerals supply chains – is reflected in Russia's various partnership agreements (Vidal, 2023).

While many agreements remain unpublished or absent in news articles, APRI’s search surfaced bilateral agreements with Zimbabwe, Angola, Namibia and South Africa (African Mining Market, 2020; Alves et al., 2013; Jansen van Vuuren, 2018; Kremlin.ru, 2021). Some of these agreements date back to 1999 (South Africa), while others were concluded more recently, such as those with Angola in 2009 and 2019, Namibia in 2016, and Zimbabwe in 2019 and 2020. A significant number of these agreements concern technical cooperation in geology and mineral exploration, as well as the sharing of information and experts. This points to Russia's unique value proposition of offering mining expertise (Vidal, 2023).

The country’s strategy of formalizing partnership agreements is complemented by what could be described as ‘security provision for mining concessions’, carried out primarily by its private military company Africa Corps, better known by its previous name “The Wagner Group”, in a dual-capacity role (Minde, 2024; Vidal, 2023). The company provides military services, personal protection for regime officials and for mining concessions and, in return, gains access to mining concessions. These arrangements reportedly occur in several countries, including the Central African Republic, Sudan, Libya, Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger (Droin & Dolbaia, 2023). These activities are further supported by the Russia-Africa Summits of 2019 and 2023 (Summit Africa, n.d.), which serve as a platform to promote formal and informal cooperation (Vidal, 2023). Given the country's limited financial resources, investments in the mineral sector, particularly in processing activities, remain scarce (Stronski, 2019).

Russia has bilateral agreements with five African states.

Angola

Mozambique

Namibia

South Africa

Zimbabwe

View Russia’s partnerships on APRI’s interactive map.

India

- Recognizing the risks associated with its overreliance on China for critical minerals, India is pursuing both domestic and international strategies to secure its supply.

- India has established mineral partnerships with nine African states, primarily in sub-Saharan Africa and often with Commonwealth members, with a focus on cooperation in exploration, geological studies, and training.

- Beyond bilateral partnerships, Indian companies, both private and state-owned, are actively investing in African mining projects. Examples include Vedanta Resources’ in Zambia and Varun Industries Limited’s in Madagascar.

In its 2023 Report on the Identification of Critical Minerals, the Indian Ministry of Mines emphasizes the crucial importance of access to critical minerals for the country's future economic development, prosperity and national security. India views access to these minerals as essential for adopting new technologies across various sectors, including electronics, telecommunications, transport, defense, agriculture and renewable energy (Ministry of Mines, 2023). Furthermore, critical minerals are necessary inputs for India’s climate goal of reducing emissions to net zero by 2070 (Jayaram & Ramu, 2024).

India’s high reliance on China for critical minerals is perceived as a substantial risk, particularly given their ongoing regional rivalry and recurrent border conflicts. China's 2010 decision to halt rare earth supplies to Japan presents similar vulnerabilities for India due to its overreliance. To address this concern, India has implemented a series of domestic and international measures (Jayaram & Ramu, 2024). Domestically, the government has introduced regulatory reforms to facilitate increased mineral exploration, conduct mineral reserve auctions and establish a center of excellence (Indian Ministry of Mines, 2023).

On the international stage, India has concluded a considerable number of mineral partnerships, including with nine African states (Indian Ministry of Mines, 2024). The majority of these partnerships are with states in sub-Saharan Africa, many of which belong to the Commonwealth along with India. One such agreement dates back to 1997 with South Africa, while the majority were signed after 2010. The agreements generally concern the cooperation on mineral exploration and geological studies as well as the provision of training. The agreements with Zambia, Zimbabwe and Mali have additional provisions for the planning of joint ventures and the promotion of investment (Indian Ministry of Mines, 2012, 2018, 2019).

Many of India’s private and state-owned enterprises operate with a considerable degree of autonomy from the government, thus making their own investment decisions on the African continent.

Many of India's private and state-owned enterprises operate with a considerable degree of autonomy from the government, thus making their own investment decisions on the African continent (Myles, 2023). Historically, Indian companies have maintained a strong presence in the coal mining sector, however, some have diversified their interests by acquiring stakes in other mines (African Business, 2012). For instance, Vedanta Resources has stakes in a Zambian copper mine, while Varun Industries Limited has a presence in Madagascar's heavy rare earth element mines (Varun Industries Ltd., n.d.; Vedanta Resources, n.d.). Vedanta’s experience in Zambia highlights the volatile and often tense relationship between external investors and state actors. Initially dismissed as a second-tier company compared to its Western and South African counterparts, it overcame skepticism to establish its Konkola Copper Mines operations. In 2019, the company exited as the Zambian government placed it in provisional liquidation, but after a multi-million dollar settlement in 2023, they returned (Vernau, 2023).

During its G20 presidency from December 2022 to November 2023, India emphasized the importance of critical mineral supply chains in the developing countries.

In addition to bilateral agreements, India is actively engaged in multilateral partnerships. India is part of the US-led MSP and has been invited to join the EU’s CRM Club (U.S. DOS, n.d.; Vishnoi, 2023). For India, these partnerships serve as a desirable counterbalance to China's dominance. During its G20 presidency from December 2022 to November 2023, India emphasized the importance of critical mineral supply chains in the developing countries (Government of India, n.d.; Jayaram & Ramu, 2024).

India has bilateral agreements with nine African states.

Côte d'Ivoire

Malawi

Mali

Morocco

Mozambique

South Africa

Tanzania

Zambia

Zimbabwe

View India’s partnerships on APRI’s interactive map.

China

- In response to growing demand and geopolitical tensions, China has updated its critical minerals strategy to diversify its supply chains and strengthen international collaboration.

- It has established an extensive network of mineral partnerships with African states, often embedded within broader cooperation agreements. These partnerships typically involve direct control of operations and the reduction in reliance on third parties.

- Chinese companies account for 8% of Africa’s mining sector output and often utilizes “infrastructure-for-resources” agreements through its Belt and Road Initiative to secure access to critical minerals.

China has recognized the strategic importance of critical minerals for several decades. Consequently, it has developed, implemented and continually updated a long-term strategy to meet its massive mineral needs. Its continued pursuit of resources and raw materials places the country in a central and dominant position in critical minerals supply chains today. In its 2016-2020 National Plan for Mineral Reserves, China published its first list of "strategic minerals" deemed essential for national and economic security. The General Fourteenth Five-Year Plan (2021-2025) emphasizes the importance of the green transition for China’s strategic sectors (Zhou et al., 2023).

China aims to become the world’s technology leader by 2035. According to analysts, the country’s substantial demand for the raw materials required for energy and technology products will likely cause supply shortages of at least nine minerals (Nakano, 2021; Zhou et al., 2023). This has raised concerns with Chinese officials and challenges the reigning narrative that China’s mineral future is secure. In reality, the country shares supply concerns with states such as the US and the EU (Cohen et al., 2023). In an increasingly tense geopolitical environment, the recent eviction of Chinese investors from Canada and the adoption of increasingly defensive unilateral mineral policies contribute to this concern (Lu et al., 2023).

By 2023, Chinese companies were responsible for 8% of the output across the African mining sector.

To mitigate the risk of supply chain disruption, China has introduced a series of domestic and international measures. Domestically, the government has ordered increased efforts for mineral exploration, the creation of strategic stocks, and the development of a warning mechanism. On the international stage, China is seeking to expand and strengthen its extensive network of diplomatic connections to foster collaboration in the minerals sector (Lu et al., 2023).

APRI’s search yielded 19 mineral partnerships between China and African states, covering regions across the continent. Many of these partnerships were concluded in the mid-2000s, some in the 2010s, along with more recent agreements. It is common practice for these agreements to be preceded by, or embedded in, a more comprehensive partnership agreement, of which China holds many (Bhole, 2023). As they are not publicly available, the specifics of these agreements are difficult to ascertain. However, some sources report on cooperation in mineral exploration, technical cooperation and the identification of joint projects (AidData, n.d.; Afrol News, 2006; Forum for Economic and Trade Cooperation between China and Portuguese-speaking Countries, 2016).

China’s geopolitical strategy for critical minerals in Africa is characterized by a high-risk appetite and an integrated supply chain approach. Chinese firms typically secure mining rights, often in high-risk regions and channel raw materials directly to processing facilities in China, minimizing reliance on third-party traders – a key differentiator from Western competitors. This strategy ensures tighter control over supply chains while advancing China’s broader economic and geopolitical goals. China’s major presence in extractive territories across Africa has also drawn criticism for its implications on human rights, including concerns about labor conditions, displacement and environmental degradation in host communities (Castillo & Purdy, 2022).

China’s substantial demand for the raw materials required for energy and technology products will likely cause supply shortages of at least nine minerals.

China has also entered into what could be termed "infrastructure-for-resources" agreements as part of its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) (Ndegwa, 2023). These agreements entail China’s provision of key infrastructure projects in exchange for African mining concessions. The most prominent of these is the Sicomines agreement with the DRC (Landry, 2018).

Additionally, the Chinese government has encouraged overseas investment by state-owned and private enterprises since the inception of its "Go Global" policy in 2000 (Zhou et al., 2023). By 2023, Chinese companies were responsible for 8% of the output across the African mining sector (Risi & Doyle, 2023). Chinese investment is particularly prevalent in the DRC, where Chinese companies own 72% of copper and cobalt mines (Bakr, 2024) and in Zimbabwe, where Chinese investment in lithium mines is on the rise (Ford, 2024).

China has bilateral agreements with eleven African states.

Algeria

Angola

Guinea-Bissau

Morocco

Mozambique

Nigeria

Rwanda

South Africa

Sudan

Zambia

Zimbabwe

View China’s partnerships on APRI’s interactive map.

South Korea

- Driven by its export-oriented economy and ambitions in critical technologies, South Korea adopted a strategy that focuses on diversifying suppliers, de-risking foreign investments and navigating its relationships with both China and the US.

- During its 2024 Korea-Africa Summit, South Korea signed bilateral agreements with Madagascar, Tanzania and Nigeria, focusing on cooperation and investment promotion.

- Furthermore, South Korea has introduced tax credits for companies to stimulate investment in overseas resource development. This approach is complemented by active engagement with the private sector.

The Republic of Korea has been publishing lists of strategic minerals since at least 2007 (U.S. Geological Survey [USGS], 2023). Its active approach to resource diplomacy, however, only began in 2020 when global attention shifted toward supply chain security. This led to the adoption of the Strategy for Securing Reliable Critical Minerals Supply in February 2023 (IEA, 2024a). This policy’s objective is to be at the forefront of the global competition for technological advancement, with the production of recently declared critical technologies (Sharma, 2024), such as semiconductors, batteries, aerospace technology and robotics. As a country with limited natural resources and an export-oriented economy, Korea has recognized its significant reliance on mineral imports from China (Dickens, 2024). In response, the government has outlined a strategy to mitigate current risks, diversify suppliers and de-risk foreign investments in mining projects. It must carefully navigate its international partnerships, given its reliance on both China as a source and market for its products and the US as a strategic ally and security partner (Sharma, 2024).

Korea’s strategy for diversifying its supply chain was evident in the recent organization of the 2024 Korea-Africa Summit, which emphasized critical raw materials (African Development Bank Group, 2024). At this event, the government signed three bilateral critical minerals agreements with three African states: two on general cooperation with Madagascar and Tanzania and one on the promotion of investment with Nigeria (Chang, 2024). The agreement with Madagascar may be related to the presence of Korean companies in Madagascar's nickel sector (Nicolas, 2020). Korea's support for such agreements is specifically outlined in its 2023 mineral strategy (IEA, 2024a).

[Korea’s] policy’s objective is to be at the forefront of the global competition for technological advancement.

In addition to state-to-state collaboration, the country has introduced tax credits for companies investing in overseas resource development to further stimulate investment (Dickens, 2024). The signing of 16 MoUs and 19 contracts between state-owned and private companies of Korea and African states during the 2024 Korea-Africa Summit has undoubtedly been considered a positive outcome by the government (Chang, 2024).

South Korea’s has bilateral agreements with three African states.

Madagascar

Nigeria

Tanzania

View South Korea’s partnerships on APRI’s interactive map.

Japan

- Triggered by a 2010 rare earth supply disruption with China, Japan developed a comprehensive minerals strategy that prioritizes domestic stockpiling, research and international partnerships.

- Japan’s agreements in Africa emphasize diversification of supply in exchange for technology transfer, infrastructure development and investment in all stages of the mineral supply chain.

- Japan’s Oil, Gas and Metals National Corporation (JOGMEC) plays a crucial role in implementing Japan’s strategy, through facilitating joint research projects, geological surveys, capacity building and financial support for Japanese companies investing in African mining projects.

As a resource-poor country, Japan has long been aware of the necessity to secure overseas natural resource supplies for its economy. In 2010, a dispute with China resulted in the latter cutting off its rare earth supply (Seth, 2024). This revealed the country's supply chain vulnerabilities and led to the development of a comprehensive minerals strategy. Japan relies on its close ties with other G7 partners to reduce its dependence on China. The country’s most recent mineral strategy is outlined in the 2022 Economic Security Protection Act and the 2023 Policy on the Initiative for Ensuring a Stable Supply of Critical Minerals (European Parliamentary Research Service, 2023; IEA, 2023). The former document specifies several products for which the importance of supply is considered critical, including permanent magnets, aircraft parts, semiconductors, storage batteries and advanced electronic components. This suggests that Japan is aiming to remain at the forefront of global technological innovation, including innovations required for decarbonization (Japanese Cabinet Office, 2023).

Japan’s agreements demonstrate a clear regional focus on Southern Africa and the Central African 'copper belt'.

Domestically, Japan has been engaged in mineral stockpiling activities as well as research on recycling and substitution strategies. In international negotiations, Japan's resource diplomacy prioritizes diversification of supply in exchange for technology transfer, infrastructure development, trade agreements and investments at all stages of the mineral supply chain (Barteková & Kemp, 2016). This strategy is evidenced by the DRC, Madagascar, Namibia, South Africa and Zambia’s bilateral agreements with Japan. Concluded between 2017 and 2023, these agreements demonstrate a clear regional focus on Southern Africa and the Central African "copper belt" (Energy Capital & Power, 2023; North Africa Post, 2023; Nyaungwa, 2023; Veras, 2018).

JOGMEC is responsible for implementing Japan's resource diplomacy strategy. It plays a central role in facilitating joint research projects, geological surveys, capacity building and long-term financial support for Japanese companies interested in investing in foreign minerals projects (Seth, 2024). As of April 2023, JOGMEC operates in South Africa, Botswana, Namibia, Angola and Zambia (Takahara, 2023). In addition to bilateral partnerships, Japan has appointed so-called "Special Assistants for Natural Resources" to diplomatic missions. These individuals are responsible for gathering further insights into the mineral sector in countries with which Japan engages in diplomatic relations (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, 2023).

Japan has bilateral agreements with five African states.

DR of Congo

Madagascar

Namibia

South Africa

Zambia

View Japan’s partnerships on APRI’s interactive map.

Indonesia

- Indonesia aims to strengthen its mineral downstream sector - particularly for strategic industries like electric vehicles - and diversify its supply chains.

- Indonesia is actively signing collaborative agreements with African states, that focus on exploration, knowledge sharing, capacity building, technology transfer and investment promotion.

- The country’s ambitious goal of becoming a leading electric vehicle battery producer by 2027 has increased interest in African mining projects amongst Indonesian investors.

When it comes to critical minerals, Indonesia’s 2020 ban on nickel ore exports has been at the center of attention (IEA, 2024b). In recent years, the country has taken significant steps to enhance its international collaboration on other critical minerals. In September 2023, Indonesia published a list of 47 critical minerals in alignment with its 2015-2035 National Development Master Plan (Indonesia Miner, 2023; KADIN Indonesia, 2024). Indonesia's overarching objective is to strengthen its mineral downstream sector, advance its strategic industries and enhance its global competitiveness and trade revenue. The plan’s selected strategic sectors include healthcare, energy generation, defense and electric vehicles. While Indonesia is rich in minerals, it is not endowed with all the critical minerals required for the production of electric vehicles. This deficit partly motivates its recent outreach to other mineral-rich countries. Another factor driving Indonesia's pursuit of diversified partnerships is its reliance on China as an export market and a significant investor (KADIN Indonesia, 2024). Furthermore, the violation of Indonesia's exclusive economic zone by Chinese fishing boats is another driving factor (Chivvis et al., 2023).

On the international stage, Indonesia has concluded agreements with several African states, including in 2008 with Libya, in 2018 with Morocco, in 2023 with Algeria and Kenya and in 2024 with Tanzania (Indonesia Window, 2021; Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Indonesia, n.d.). These agreements include cooperation on the exploration of reserves, knowledge sharing and joint studies, capacity building, policy cooperation, technology transfer, processing and value addition, as well as joint projects between companies and the promotion of investment.

With the agreements enacted, Indonesian investors have announced their interest in mining projects in Africa, particularly in Tanzania, the DRC and Zimbabwe. There is a particular focus on graphite and lithium, as Indonesia requires them for its electric vehicles sector (Barich, 2023).

In addition to state-to-state cooperation and investments, the second Africa-Indonesia Forum in September 2024 focused on critical minerals (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Indonesia, 2024). Indonesia has set an ambitious goal of becoming the world’s third-largest producer of electric vehicle batteries by 2027, capitalizing on its substantial nickel reserves to establish an integrated domestic electric vehicle supply chain (Otieno, 2024). At the forum, Indonesia also identified Africa as a potential source of lithium. Concurrently, Kenya stands to benefit from a bilateral sustainable energy agreement with Indonesia aimed at advancing the Suswa Geothermal Project and enhancing electricity connectivity and reliability, in line with the government's commitments under the Kenya Kwanza Initiative (Geothermal Development Company, n.d.).

Indonesia has bilateral agreements with five African states.

Algeria

Libya

Morocco

Kenya

Tanzania

View Indonesia’s partnerships on APRI’s interactive map.

United States

- Driven by economic security, national defense, and climate commitments, the US is prioritizing domestic production of critical minerals. It does this by providing financial incentives to source minerals domestically or from countries with free trade agreements in place.

- The US is selective about its critical mineral-related bilateral agreements with African states. Notable initiatives such as the Lobito Corridor for mineral transportation are enabled by a broad range of partnership arrangements.

- The US primarily fosters collaboration with its allies through multilateral initiatives like the Minerals Security Partnership and the Energy Resource Governance Initiative.

The US mineral policies date back to the Second World War.5 More recently, its activities are based on two key pieces of legislation: the 2020 Energy Act and the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act (IEA 2022, 2024c). Both are driven by the US's economic security and national defense concerns and its climate commitments to reach net zero by 2050 (Deberdt, 2024; U.S. Department of Commerce, n.d.). The issue is compounded by the country's reliance on critical minerals imports and the fact that many minerals are sourced from countries that the US deems a "foreign entity of concern," such as China, Iran, North Korea and Russia (Deberdt, 2024).

In response, the US has developed a strategy that prioritizes expanding domestic production of critical minerals. This strategy includes offering financial incentives and attracting international investments in the country's mineral sector (Deberdt, 2024). The provision of financial incentives is subject to certain conditions, including that the minerals in question be sourced predominantly domestically or from countries with which the US has a free trade agreement. In Africa, Morocco stands to benefit from these provisions, given its free trade agreement with the US (Office of the United States Trade Representative, n.d.).

The US primarily fosters collaboration through multilateral institutions at the international level.

Regarding international cooperation, the most tangible initiative between the US and African states is the “MoU on the Support for the Development of a Value Chain in the Electric Vehicles Battery Sector” with the DRC and Zambia. The cooperation agreement, adopted in December 2022, encompasses feasibility studies, technical assistance provision and investment encouragement. The 2023 MoU on the Development of the Lobito Corridor and the Zambia-Lobito Rail Line, signed by the Africa Finance Corporation, the African Development Bank, Angola, the DRC, the EU, the US and Zambia, is not directly related to the sourcing or processing of minerals but rather their transportation (US Embassy in Zambia, 2023).

In addition to these two initiatives, the US primarily fosters collaboration through multilateral institutions at the international level. One example is the US-led MSP, which includes 15 partners and 15 new forum members, predominantly G7 countries (European Commission, 2024c; US DOS, n.d.). Another multilateral initiative is the Energy Resource Governance Initiative, where the US has formed a partnership with the resource-rich countries of Australia, Botswana, Canada and Peru (US DOS, 2020a). The initiative was launched in 2020 to share best practices, bolster investment frameworks and foster mineral supply chains that are less reliant on China (US DOS, 2020b).

Beyond the US multilateral initiatives, the US International Development Finance Corporation is the primary US institution investing in overseas mineral projects (Seth, 2024). As of March 2024, however, only 1.2% of its financed projects were related to the mining sector (Baskaran, 2024).

The US has bilateral agreements with two African states.

Zambia

DR of Congo

View the US’s partnerships on APRI’s interactive map.

European Union

- Prompted by rising global demand and supply vulnerabilities, the EU launched its Raw Materials Initiative in 2008 and has since prioritized securing critical raw materials for its green and digital transitions.

- The EU’s partnerships with African countries are often channelled through multilateral intiatives, and aim to promote trade, investment and sustainable development in the mineral sector.

- Key EU actors, like the European Investment Bank, are also investing in the mineral sector, supporting the EU’s overall goal of securing critical raw materials while promoting responsible and sustainable practices.

From the early 2000s, a surge in global demand for metals, largely driven by the rapid growth of emerging economies, led to a tripling of metal prices by 2008 (European Commission, 2008). While the financial crisis of 2008 slowed demand, growth in emerging economies kept pressure on raw material supplies, leading to a situation where demand outpaced supply (Szczepanski, 2019). In response, the EU’s Raw Materials Initiative was launched in 2008, and since 2011, the EU has published lists of CRMs at three-year intervals (European Commission, 2008; 2011).

In March 2022, the European Commission prepared a Communication on the new European Growth Model, in which it highlighted three sectors as top priorities: the green transition, the digital transition and the strengthening of EU resilience through secure supply chains and increased defense capacities (European Commission 2022a, 2022b, n.d. [a]; EU, 2022). These sectors have an immense need for secure access to raw materials. To ensure future supply stability and reduce its dependence on single suppliers such as China, the EU has adopted a series of domestic measures and initiated the diversification of its international suppliers, as codified in the 2024 EU Critical Raw Materials Act (European Commission, n.d. [b]).

To ensure future supply stability and reduce its dependence on single suppliers such as China, the EU has adopted a series of domestic measures.

The EU's strategy for diversifying its supply chain includes establishing raw materials partnerships (European Commission, n.d. [c]). Four partnerships have been concluded with African states: Namibia (2022), the DRC, Zambia (2023) and Rwanda (2024) (European Commission 2022c, 2023a, 2023b, 2024d). Minor differences exist between the agreements, for instance, regarding the definition of critical and strategic materials. The agreement with Namibia and Zambia adopts the EU's definition of critical minerals, whereas the agreement with Rwanda mentions non-energy, non-agriculture raw materials but does not specify further (Critical Minerals Coalition, 2021).

Nevertheless, all four partnership agreements rest on five main pillars:

- The integration of mineral value chains and promotion of trade and investment linkages through joint ventures, networking events and the joint identification of bankable projects.

- The mobilization of EU private and public funds for infrastructure projects.

- The exchange of knowledge and technology.

- Skills development and capacity building.

- Cooperation to enhance the observance of environmental, social and governance (ESG) principles.

The agreement with Namibia includes an additional pillar of cooperation in the renewable hydrogen sector. Namibia can produce renewable hydrogen at competitive prices, which is crucial for the EU as it looks for sustainable alternative energy sources. In return, Namibia aims to use hydrogen exports to boost its economy, create jobs and improve access to energy and water (Nweke-Eze, 2023).

Additionally, the EU introduced the Global Gateway initiative, which serves to counter China’s (European Commission, n.d. [e]; McBride, 2023). The Global Gateway initiative focuses on sustainable infrastructure, health, education and climate change to drive Africa's socioeconomic, green and digital transformations. A central aspect of the initiative is its dedication to attracting private sector investments and its commitment to realizing the multiplier effect of resource rents (Statista, 2024).

Aside from the Global Gateway initiative, the EU has a financing mechanism for infrastructure projects. Named the Africa MaVal initiative, it identifies bankable projects and supports capacity building in the minerals sector (AfricaMaVal, n.d.). The EU has also announced the formation of a new multilateral initiative, the EU CRM Club, which became a part of the MSP Forum, to establish a more extensive and ambitious collaborative initiative connected to the MSP (European Commission, 2024a; Findeisen, 2023).

Key EU actors such as the European Investment Bank (EIB) and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development are actively involved in investments in the mineral sector to complement these initiatives. For example, the EIB signed the Critical Raw Materials Investment Partnership with Rwanda in December 2023 (European Investment Bank, 2023).

The EU and 14 other countries launched the MSP in 2022, which aims to advance the development of diverse and sustainable supply chains for critical energy minerals by collaborating with host governments and industry and providing targeted financial and diplomatic support for strategic projects across the value chain. Projects are only supported if they meet high ESG standards, promote local value addition and allow all participating countries to profit from the clean energy transition (US DOS, n.d.). The MSF Forum was launched in 2024, and among the new members are two African countries: the DRC and Zambia.

The EU has bilateral agreements with four African states.

Namibia

DR of Congo

Rwanda

Zambia

View the EU’s partnerships on APRI’s interactive map.

Endnotes

[1] An upcoming APRI report will focus specifically on the story of African agencies in the global race for green minerals to secure benefits and influence the direction of these partnerships.

[2] Individual European countries also participated in multilateral partnerships such as MSP.

[3] The mapping relied on qualitative analysis of government websites of both African and non-African actors, as well as news and research articles. These were collected based on a Google search conducted between June and October 2024 using combinations of keywords such as “mineral,” “raw materials,” “mining,” “bilateral,” “agreement,” “partnership,” “memorandum of understanding,” “MoU,” “cooperation,” and “signed.” Newspapers consulted include nine African national newspapers (such as Lusaka Times (https://www.lusakatimes.com/) or The Independent Nigeria (https://independent.ng/about-us/)), eight African regional newspapers (such as The North Africa Post (https://northafricapost.com/) or The East African (https://www.theeastafrican.co.ke/)), and 15 non-African newspapers (such as Yonhap News (https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20240605007151320) or The Economic Times India (https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/indl-goods/svs/metals-mining/mines-minister-narendra-singh-tomar-invites-global-firms-to-invest-in-india/articleshow/46213029.cms?from=mdr)). In addition, information was retrieved from six government websites (such as Nigeria’s ministry (https://fmino.gov.ng/) for Information and National Orientation and India’s Ministry (https://mines.gov.in/webportal/home) of Mines) and from articles by four research organizations that cited mineral partnerships (such as the South African Institute of International Affairs (https://saiia.org.za/) or the Arab Gulf States Institute (https://agsiw.org/)). Eight agreements were found through the Food and Agriculture Organization’s database (https://www.fao.org/faolex/background/en/) of bilateral agreements on natural resource management.

[4] As mentioned above, natural resource deals are inherently opaque, and governments often avoid publishing or even mentioning them after approval. National newspaper agencies, which offer the best hope of finding information, have different publication frequencies and capacities to cover events in a country. Thus, countries with less active national news agencies may be underrepresented. Furthermore, some newspaper articles become inaccessible after a period, as evidenced by broken links to partnership agreements that research organizations cited. Similarly, the accuracy of the content of the agreements, when retrieved from newspaper articles, depends on the newspaper's capacity to report correctly and comprehensively.

[5] The atomic weapons dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki were developed using uranium from a mine in the Congo https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20200803-the-forgotten-mine-that-built-the-atomic-bomb.

Bibliography

Adebayo, T. (2024, October 31). Nigeria, UK to form technical committee on mining development. Independent Nigeria. https://independent.ng/nigeria-uk-to-form-technical-committee-on-mining-development/

AfricaMaVal. (n.d.). Objectives. https://africamaval.eu/objectives/

African Business. (2012, January 16). Mining: India throws down the gauntlet. African Business. https://african.business/2012/01/economy/mining-india-throws-down-the-gauntlet

African Development Bank Group. (2024). 2024 Korea-Africa Summit. https://www.afdb.org/sites/default/files/documents/en_leaflet-2024_korea-africa_summit.pdf

African Mining Market. (2020, November 16). Zimbabwe and Russia sign exploration, mining MoUs. https://africanminingmarket.com/zimbabwe-and-russia-sign-exploration-mining-mous/8449/

African Union. (n.d. [a]). African mining vision. https://au.int/en/ti/amv/about

Afrol News. (2006). China, Angola sign 9 cooperation agreements. http://www.afrol.com/articles/15848

Agora Strategy Group. (2023). Re-calibrating interdependence: The geopolitical rivalry for critical raw materials. https://www.agora-strategy.com/post/re-calibrating-interdependence-the-geopolitical-rivalry-for-critical-raw-materials-1

AidData. (n.d.). China and Sudan sign cooperation agreement on mineral resources. https://china.aiddata.org/projects/30432/

Al Jazeera. (2023, June 2). A ‘Russian love affair’: Why South Africa stays ‘neutral’ on war. Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2023/6/2/a-russian-love-affair-why-south-africa-stays-neutral-on-war

Alves, A. C., Arkhangelskaya, A., & Shubin, V. (2013). Russia and Angola: The rebirth of a strategic partnership? South African Institute of International Affairs. https://saiia.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Occasional-Paper-154.pdf

Anglo American. (n.d.). Products. https://www.angloamerican.com/products

Anyanwu, S. (2024, October 28). Nigeria, Saudi Arabia pledge collaboration on mining sector development. Federal Ministry of Information and National Orientation. https://fmino.gov.ng/nigeria-saudi-arabia-pledge-collaboration-on-mining-sector-development/

Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington. (n.d.). Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington. https://agsiw.org/

Alqarout, A. (2023). Saudi Arabia pushes ahead to become a global mining player. Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington, October 26. https://agsiw.org/saudi-arabia-pushes-ahead-to-become-a-global-mining-player/

Bakr, S. (2024). Saudi Arabia’s and the UAE’s quest for African critical minerals. Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington. https://agsiw.org/saudi-arabias-and-the-uaes-quest-for-african-critical-minerals/#:~:text=Minerals%20such%20as%20copper%2C%20cobalt,in%20the%20clean%20energy%20sector

Barich, A. (2023). Indonesia looks to Australia, Africa for minerals to meet its EV hub ambitions. S&P Global Commodity Insights. https://www.spglobal.com/commodityinsights/en/market-insights/latest-news/metals/032923-indonesia-looks-to-australia-africa-for-minerals-to-meet-its-ev-hub-ambitions

Barteková, E., & Kemp, R. (2016). Critical raw material strategies in different world regions. UNU-MERIT Working Papers. https://unu-merit.nl/publications/wppdf/2016/wp2016-005.pdf

Bartosiewicz, M. (2023). Controlled chaos: Russia’s Africa policy. OSW Commentary. Centre for Eastern Studies. https://www.osw.waw.pl/en/publikacje/osw-commentary/2023-08-23/controlled-chaos-russias-africa-policy

Baskaran, G. (2024). How to reform the DFC to meet U.S. critical minerals security needs. Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). https://www.csis.org/analysis/how-reform-dfc-meet-us-critical-minerals-security-needs

Bhole, O. (2023). China’s partnerships with the world. ORCA Asia. https://orcasia.org/article/347/chinas-partnerships-with-the-world

Bianco, C. (2024). Global Saudi: How Europeans can work with an evolving kingdom. European Council on Foreign Relations. https://ecfr.eu/publication/global-saudi-how-europeans-can-work-with-an-evolving-kingdom/

Bilal, S., & Teevan, C. (2024). Global Gateway: Where now and where to next? ECDPM Discussion Paper. https://ecdpm.org/application/files/1617/1776/7785/Global-Gateway-Where-now-and-where-to-next-ECDPM-Discussion-Paper-2024.pdf

Campbell, R. (2022). The UK and South Africa announce joint development, investment partnerships. Engineering News. https://www.engineeringnews.co.za/article/the-uk-and-south-africa-announce-joint-development-investment-partnerships-2022-11-22

Castillo, R., & Purdy, C. (2022). China’s Role in Supplying Critical Minerals for the Global Energy Transition: What Could the Future Hold? The Leveraging Transparency to Reduce Corruption project (LTRC). https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/LTRC_ChinaSupplyChain.pdf

Chang, D. (2024, June 5). (LEAD) S. Korea-Africa summit paves way for stronger cooperation on trade, energy, economy. Yonhap News Agency. https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20240605007151320

Chivvis, C. S., Noor, E., & Geaghan-Breiner, B. (2023). Indonesia in the emerging world order. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2023/11/indonesia-in-the-emerging-world-order?lang=en

Cohen, J., Shirley, W., & Svensson, K. (2023). Resource realism: The geopolitics of critical mineral supply chains. Goldman Sachs Global Institute. https://www.goldmansachs.com/insights/articles/resource-realism-the-geopolitics-of-critical-mineral-supply-chains

Critical Minerals Coalition. (2021). Defining criticality - what makes a critical mineral? https://www.criticalmineral.org/post/defining-criticality-what-makes-a-critical-mineral

Daily Sabah. (2020, January 20). Turkey to conduct mineral exploration activities in Niger. https://www.dailysabah.com/business/2020/01/20/turkey-to-conduct-mineral-exploration-activities-in-niger

de Kluiver, J. (2023). Navigating the complex terrain of China-Africa debt relations. Institute for Security Studies. https://issafrica.org/iss-today/navigating-the-complex-terrain-of-china-africa-debt-relations