Summary

- The Lobito Corridor is being hailed as a game changer, echoing the acclaim once given to its ‘spinal cord’, the Benguela Railway, which was also celebrated as transformative when completed nearly a century ago.

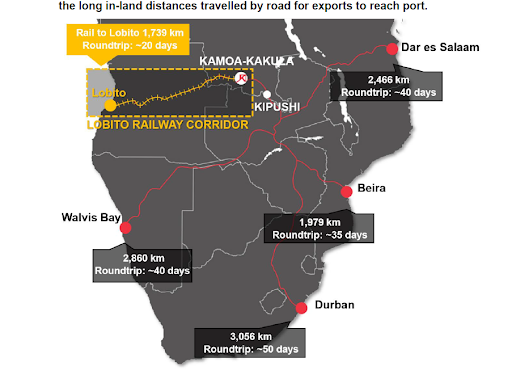

- The Corridor provides a cheaper, quicker route for transporting critical raw materials (CRMs) from the Copperbelt of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Zambia to the Port of Lobito for onward export. The savings in logistics and transportation costs are of such magnitude that they could make previously uneconomical ore grades viable to mine.

- The players involved in the Corridor’s development cover a broad spectrum, from state actors to multilateral institutions, to financiers and private players.

- Although the Corridor is lauded as an enabler of local value addition on a scale not seen before in the region, there are sceptics who fear it may facilitate ‘modern plundering’ by removing the friction of exporting unprocessed ore. There are also concerns over the enforcement of sustainability, transparency and ethical sourcing in CRM value chains in the region.

- The Lobito Corridor is said to exemplify a shift in US engagement with Africa from exploitative models to collaborative and equitable partnerships. Finance commitments by the US are alleged to be in the region of USD 4 billion. However, uncertainty looms over the future of US involvement amidst the Trump administration’s capricious approach to trade and investment.

The Lobito Corridor: A game changer

The new developments of the Lobito Corridor cannot be explored in isolation from the Corridor’s ‘spinal cord’, the Benguela Railway, which has been in existence for almost one hundred years. Just as the Lobito Corridor is taking centre stage in the green energy transition, the Benguela Railway was touted a ‘game changer’ at the turn of the 20th century. However, while it was initially hailed for its potential to revolutionise mineral ore transportation from the Copperbelt of Katanga and Northern Rhodesia to the port of Lobito on the west coast of Africa, the railway ultimately fell into disrepair due to neglect and persistent regional conflicts. Efforts to bring the railway back into use started two decades ago when a state-run Chinese company was retained to rehabilitate the line through an oil-for-infrastructure deal worth USD 1.83 billion. However, since the end of the rehabilitation 10 years ago, little use seems to have been made of the line. This may have led to the granting of a concession to operate and manage the line to the Lobito Atlantic Railway (LAR) consortium, comprising Mota-Engil (Portuguese), Trafigura (Singaporean) and Vecturis (Belgian), who have also championed the Lobito Corridor concept. It would appear the concession has spurred renewed interest in the Benguela Railway with yet again the promise of a quicker western route to Europe for metals and minerals produced in the DRC.

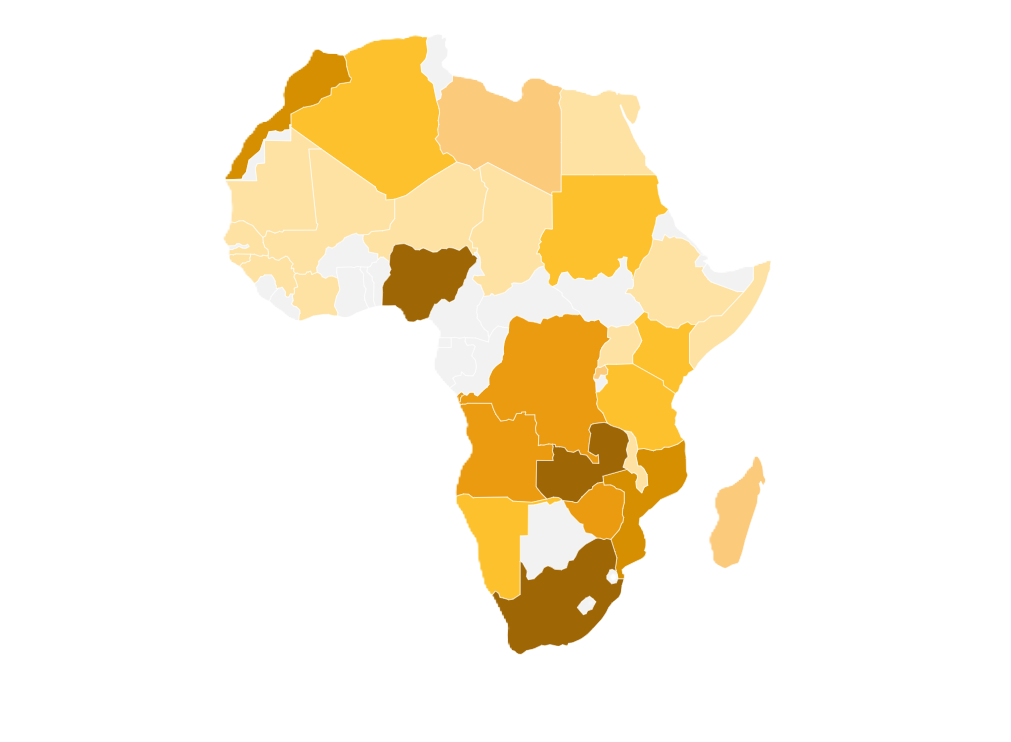

While it would seem prudent to temper today’s expectations for the Lobito Corridor with the lessons of the Benguela Railway, hopes are running high, and with good reason. Firstly, the Corridor will be the fastest route to transport critical raw materials (CRMs)1 from Central Southern Africa to the African west coast for export to the US, the EU, and other importing regions. This is key, since, despite the fact that CRMs are integral to industries such as high technology, energy, defence, and infrastructure, as well as the green energy transition, their supply chains are increasingly vulnerable to geopolitical tensions, resource nationalism and market fluctuations. For instance, the centres of demand for the CRMs sourced from this Central Southern African region are poles apart, both literally (east-to-west) and politically. In addition, not only do the Chinese dominate mining operations in the region, their Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has made significant contributions to infrastructure developments, both in the region and on the continent. The EU and US are responding with the G7 Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII). Many of the investments in the Corridor originate from this entity.

The second cause for excitement in the Lobito Corridor and the railway running through it stems from the huge savings in transportation time and cost some claim will be made. These are even expected to unlock the economic potential of some previously unfeasible ore bodies. The trial shipment of 1,100 tons of copper ore from Kolwezi in DRC to the Port of Lobito in Angola by the miner Ivanhoe demonstrated this (see Figure 1). Indeed, the infrastructure could boost mining activity on the Copperbelt of the DRC and Zambia, possibly extending to neighbouring parts of Angola where new discoveries may further strengthen the region’s role in global mineral supply chains. It is hoped that this would, in turn, expand opportunities for local value addition, industrial development and downstream beneficiation, which are central to these three countries’ national interest.

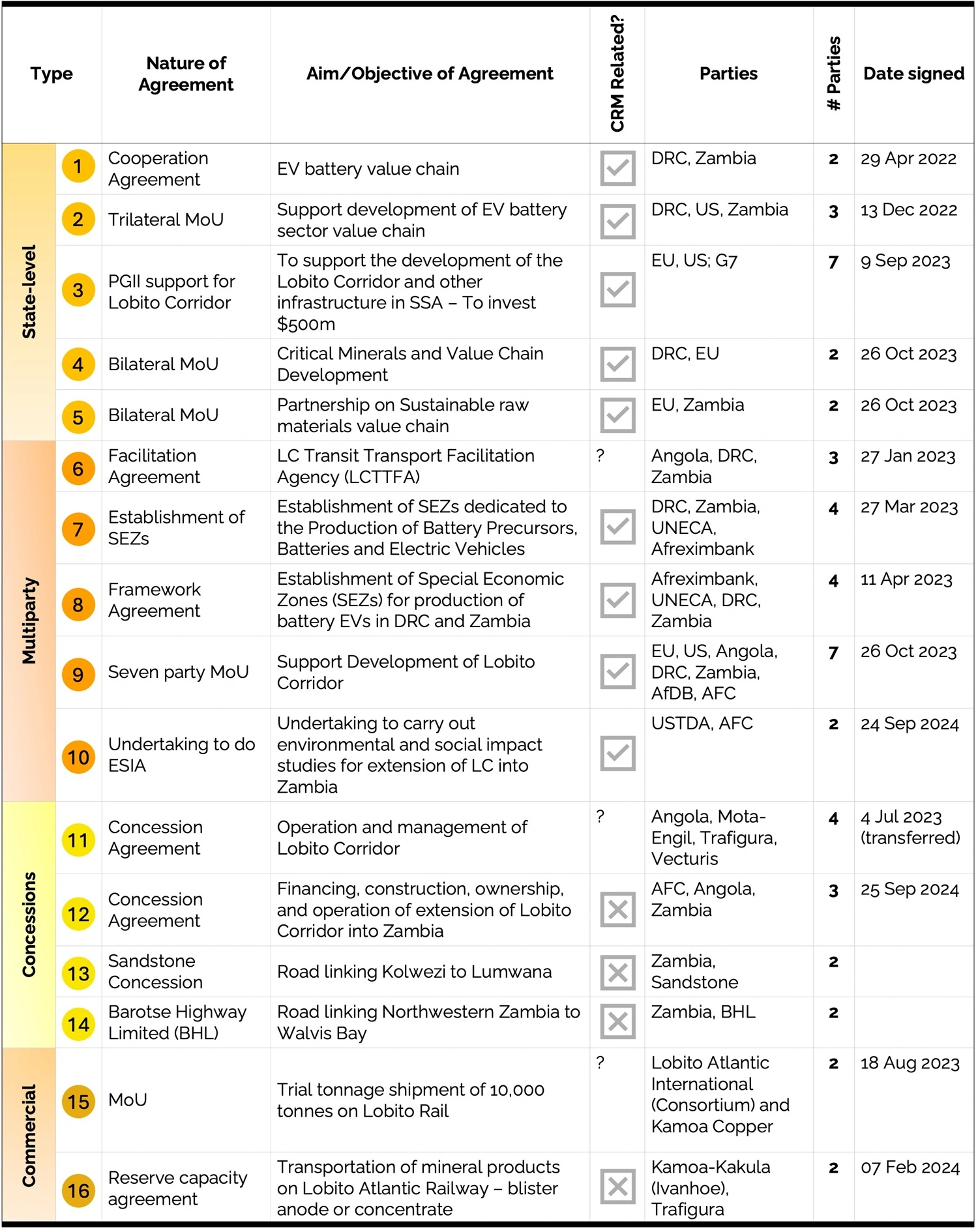

Indeed, the Corridor is seen to be game changing because of its potential to stimulate broader economic development in the region. The LAR consortium has championed the Corridor as not just a railway line for transporting mineral ores, but as an enabler for value addition and industrialisation in the areas along the route. Meanwhile, the US claims that the Lobito Corridor exemplifies a shift in its engagement with Africa, from exploitative models to collaborative and equitable partnerships. The many agreements and memoranda of understanding (MoUs) around the Corridor underscore this, at least in writing (see Table 1, below, for a list of key MoUs).

The potential of the Lobito Corridor has seen unprecedented financial support for African infrastructure development from the EU, the US and some institutions to the tune of up to USD 6 billion. However, adverse developments could emerge from the Trump Presidency, which may curtail some of the funding. This may particularly be the case with federal funding and USAID-funded projects, some of which support value-adding activities proposed for the Corridor. Furthermore, sustainability risks are increasingly part of the discourse around the Corridor, especially given the prevalence of both Chinese and informal miners along the route, posing challenges to the monitoring and regulation of social and environmental impacts.

This paper explores recent developments, and emerging opportunities surrounding the Corridor’s development and is structured as follows: It starts with an overview of the players shaping the Corridor’s development. It then delves into the Corridor’s industrialisation agenda. This is followed by an exploration of the new commitments to utilisation and financing of the Corridor. Thereafter, the paper unpacks the route’s socio-environmental risks and the impact of the Trump presidency on its development, before drawing to a conclusion.

Players shaping the Corridor’s development

There are many players involved in the re-establishment of the Lobito Corridor. The primary state actors include Angola, the DRC and Zambia. Tanzania is being considered in the plan to extend the Lobito Corridor to the Indian Ocean coast via the TAZARA railway line. Other state actors include investment and capacitation partners in the EU, the US and China. Whatever the case, commentators highlight that there are likely to be winners and losers with the development of the Lobito Corridor. For one, the Corridor will likely divert trade flows away from Southern African ports.

While the US has prioritised the development of the Corridor under the PGII, China’s entrenched role in regional infrastructure and resource extraction remains significant. The country financed and rehabilitated 1,300 km of the Benguela railway line less than a decade ago, cementing its role as a key geopolitical player. Further, it is significant that China also put in a bid for the concession to operate the line, which it lost. However, the fact that it is currently building the USD 6 billion Lobito Refinery, guaranteed by the Angolan government, underscores its continued influence in Angola. It also remains Angola’s top trading partner.

In addition, Chinese firms dominate CRM mining in the area. According to the Atlantic Council, Chinese companies own or hold stakes in fifteen of the DRC’s nineteen cobalt mines. The country has also made substantial investments in Zimbabwe’s lithium sector, further securing its role in Africa’s battery metals supply chain. Meanwhile, the China Civil Engineering and Construction Corporation (CCECC) has clinched the concession to manage the TAZARA railway for 30 years at a price tag of USD 1.4 billion for rehabilitation and the acquisition of rolling stock.

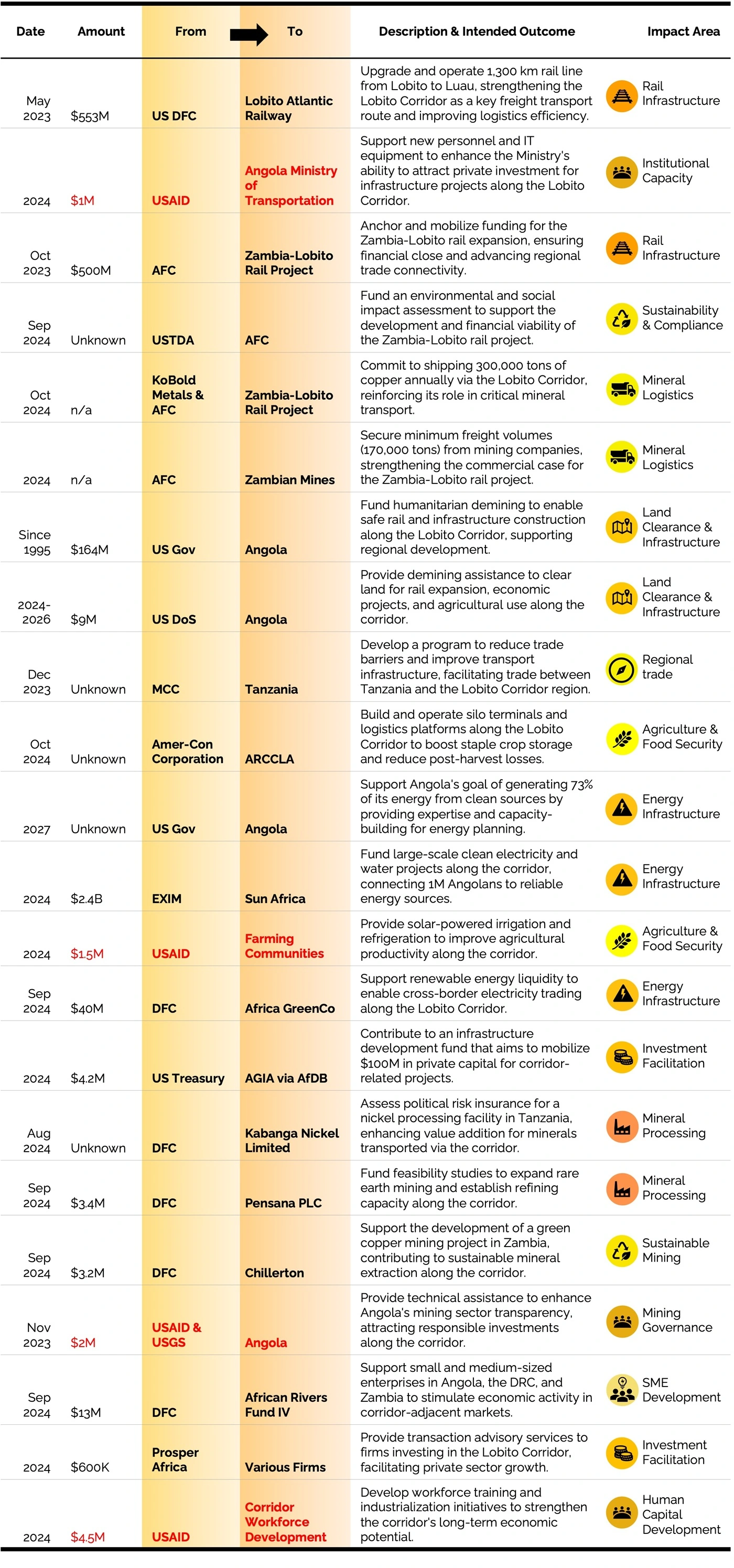

Among the key financiers of the Lobito Corridor are the US Development Finance Corporation (DFC), Afreximbank, the Africa Finance Corporation (AFC), the African Development Bank (AfDB), the Development Bank of Southern Africa (DBSA), the US Trade and Development Agency (USTDA), USAID and the World Bank. Meanwhile, the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA) is being introduced by the AFC to support infrastructure development within Special Economic Zones (SEZs) linked to the Corridor.

The private players include the concessionaires themselves: Mota-Engil, Trafigura and Vecturis. Mining companies with operations near or along the Corridor are also critical to its success. Even if they are not directly invested in its development, they should be counted among its key players. The sheer volumes they may commit to transporting along the route alone make a commercial case for the line.

The above players are tethered by a series of agreements (see Table 1).

The Corridor’s industrialisation agenda

Much of the discourse around the Corridor’s development calls for going beyond the mere exploitation and transportation of CRMs to stimulate local value addition in source countries. If the African countries concerned negotiate properly, interest in the Corridor could spur up- and downstream industrial activities, which are more sustainable drivers of economic growth than the export of primary commodities.

The commitment to go beyond the transportation of CRMs out of the mineral rich DRC and Zambia positions the Lobito Corridor as game-changing for the energy transition. This was demonstrated by the Biden administration’s claim that the Lobito Corridor exemplifies a shift in its engagement with Africa from exploitative models to collaborative and equitable partnerships which include value addition and establishment of electric vehicle (EV) value chains. The same is underscored in various MoUs, such as the trilateral one between the DRC, Zambia and the US; and the bilateral ones between the DRC and the EU, and the EU and Zambia (see Table 1).

Indeed, of the thirteen agreements related to the transportation of mineral products from the DRC and Zambia to the Lobito Port, six reference the local establishment of EV battery sector value chains. A case in point is the cooperation agreement between the DRC and Zambia, which aims to establish SEZs dedicated to the manufacturing of batteries, battery precursors, electrodes and other key components. As part of this initiative, both countries have signed a facilitation agreement to streamline investment, infrastructure development and regulatory coordination for these industrial hubs.

Following the signing of agreements by Afreximbank, UNECA, the DRC and Zambia, suitable sites for SEZs have been identified in Katanga Province of the DRC and in Ndola in the Copperbelt Province of Zambia. Afreximbank is to conduct pre-feasibility studies on these sites. Meanwhile, Zambia has been seeking a strategic partner to work with to establish EV battery value chain activities in their SEZ, while some research institutions are undertaking studies in EV battery and precursor manufacturing.

The establishment of SEZs for value-addition to CRMs in the DRC and Zambia is supported by a 2021 Bloomberg study which found that EV battery precursor manufacturing could be three times cheaper in the DRC than in the US or China, making it a competitive location. However, critics remain sceptical, arguing that efforts to link EV battery value chains to the EU and the US may be misguided. They observe that EV technology, battery manufacturing and supply chain developments are far more advanced in Asia, particularly in China, which dominates battery production, processing capacity and technological innovation. Given China’s dominance in the EV battery and vehicle space, some analysts question whether aligning with Western markets – rather than leveraging partnerships with established Asian players – will yield the most competitive and sustainable outcomes for African producers.

Others have expressed lingering fears that, by removing the friction of exporting unprocessed ore to the West, the Lobito Corridor will be a facilitator of ‘modern plundering’. With regard to investing in local value addition, reports indicate that nothing concrete has yet materialised and that there is little in the project framework that boosts prospects for this. For sceptics, any hope of achieving the type of sustainable green industrialisation sought after by African states is aspirational at best. In Zambia, for example, some see the Lobito Corridor merely as a risk mitigating measure for the export and import of goods should other routes be disrupted, as has been the case in the past.

Recent commitments to utilisation and financing

Though there are doubts as to the Lobito Corridor’s ‘game-changing’ potential, a complex framework of commitments and agreements is emerging which promises to boost shipping volumes along the route in the short to medium term. As indicated above, in late 2023, Ivanhoe of the Kamoa-Kakula Copper Complex in the DRC transported 1,100 tons of a total 10,000 tons of copper ore from Kolwezi to the Lobito Port. This provided evidence for the Corridor’s dramatic improvements in transportation time compared to other routes (See Figure 1). Movement of the balance of the 10,000 ton trial cargo continued through 2024.

Other new developments include Kamoa-Kakula and Trafigura signing a reserve capacity agreement to allocate Kamoa-Kakula between 120,000 and 240,000 tons of copper per year to be transported on the Lobito Corridor for five years, starting in 2025. The expectation is that the Corridor will ramp up export capacity to one million tons a year before 2030. Other commitments include the transport of 300,000 tons from Kobold Metals and 170,000 tons from other mines on the new railway spur from Luacano to Chingola.

Major new developments in financing include the USD 500 million announced by the AFC during the visit of President Biden to Angola in December last year. This is to go towards the construction and operation of the Lobito Corridor extension into Zambia. Another significant financing deal is the USD 600 million committed by President Biden towards the Lobito Corridor development. Earlier in 2023, the DFC provided a USD 553 million loan to the LAR concessionaires for the redevelopment and rehabilitation of the railway line from Luau (Angola) to Kolwezi (DRC). Around the same time, the DBSA approved an additional USD 200 million.

The DFC also announced the funding of feasibility studies to expand the Rare Earth Elements (REEs) mining at Longojo near Huambo along the Corridor in Angola. REEs are crucial for wind turbines, electric motors and other clean energy technologies. Pensana Plc, the mine operator, also intends to set up a REE refinery.

The proposed Zambia-Lobito greenfield rail project has also taken shape, with indications that it may pass through, or close to, some established mining operations in Zambia, subject to physical ground inspection. These include First Quantum Minerals’ (FQM) Sentinel and Kansanshi, Barrick’s Lumwana and Konkola Copper Mines’ (KCM) Konkola operations. Kobold’s Mingomba, still under development, is also included (see Figure 2).

As part of broader efforts to expand the corridor into Zambia, the USTDA awarded USD 2 million to the AFC to conduct an Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) for the planned extension. Although AFC, as the developer of the new line from Luacano to Chingola, has committed to break ground by the beginning of 2026, it was still building its commercial case through 2024 by lobbying mining houses along the proposed route to commit shipping volumes. The team will reportedly do the physical inspection of the proposed line route in the first quarter of 2025.

While it is claimed that between USD 4 billion and USD 6 billion has thus far been committed to the development of the Lobito Corridor, it has been difficult to pin down all the details of the funding.

Sustainability and socio-economic issues

Efforts to promote more responsible mining practices connected to the Corridor are being driven by the US and the EU, who aim to enhance sustainability, transparency and ethical sourcing in critical mineral supply chains. For the US, the Minerals Security Partnership (MSP) – a coalition of 14 2 countries and the EU – seeks to push this agenda. The initiative underscores that ‘the minerals industry – from mining to processing and recycling – has a duty to operate responsibly and equitably’. However, given the scepticism of the Trump Presidency towards issues of sustainable development, the US may well pull out of its commitments to promote sustainable mining practices.

Meanwhile, the EU has taken a regulatory approach through the European Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA), which aims to secure and diversify Europe’s supply of essential minerals. Additionally, the MoU the EU has signed with the DRC and Zambia emphasises sustainable mining, processing and value chain development and commits to greater social and environmental responsibility in mineral sourcing.

However, as indicated above, the bulk of CRM extraction is being undertaken by China, where such commitments to sustainable mining practices are either lacking, less stringent or inconsistently enforced. This raises questions of whether the measures undertaken by the EU and the US will be of any consequence, or if African countries could draw from them to push for better local mining practices overall.

So far, on-the-ground reports provide little evidence of more ethical mining practices. The human rights records of DRC cobalt mines are said to be ‘egregious, which local processing could exacerbate’. The increased demand for mining enabled by the Corridor may therefore serve to scale up the risk of human rights violations, contrary to its claims and the expectations of its stakeholders. The DRC continues to lag behind on protection for human rights, labour rights and basic political freedoms, as shown in Figure 3 below.

Furthermore, a report by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) notes that the expansion of the Corridor will require significant land access, which presents several challenges. In many of the areas around the Corridor, land tenure systems combine private and customary ownership. In the case of the latter, some land is often held in informally documented communal systems where large parts of the population are dependent on small-scale agriculture to support themselves. Therefore, land acquisition may result in the relocation of residents, raising questions about compensation, consent and the protection of marginalised peoples.

In addition, as shown in Figure 3 below, the Corridor project passes through areas with relatively low Human Development Index (HDI) scores, underscoring both the vulnerability of populations in these areas and the promise that the Corridor’s infrastructure may bring.

What complicates matters further is that CRM extraction has historically been undertaken by artisanal and small-scale miners (ASM), a trend which is set to increase. The governance of ASM presents significant challenges, not least because their informal nature makes it difficult to trace, monitor and regulate issues such as child labour, unsafe mining practices, toxic exposure and the formation of criminal networks. Figure 4 depicts the major sustainability challenges in CRM extraction.

Impact of the Trump Presidency

Donald Trump’s re-election has the potential to significantly impact US involvement in the Lobito Corridor project, casting uncertainty over its future. While the project aligns with the administration’s stated focus on critical minerals, apparent concerns over its viability highlight how Trump’s leadership has introduced unpredictability into strategic investments. A consequence of this equivocation could be that the project ends up in the hands of the Chinese.

Even if the US and EU purportedly remain engaged, some US funding has been indefinitely frozen, creating further instability. According to Bloomberg, the freeze affects funding for feasibility studies, technical services and crucial early-stage payments, leaving the project’s trajectory in question. A key concern is the rehabilitation of the railway line in the DRC, a critical component of the Corridor’s infrastructure. In December 2024, the US and EU signed an agreement with the DRC to assess the project, which sources estimate could cost up to USD 1 billion to rehabilitate. There are concerns regarding whether the US will honour its part of this agreement. USAID initiatives have also been stalled. This includes USD 250,000 to explore financial models for railway renovation, and a USD 5 million request for an updated pre-feasibility study remains in limbo.

Meanwhile, the recently appointed chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Subcommittee on Africa emphasised that China and energy will be key Republican foreign policy concerns. This suggests that US engagement with Africa will likely pivot from a development-oriented approach to one primarily serving US strategic interests. This raises a critical question: Will the Corridor still deliver transformative benefits for Africa, or will its game-changing potential be diminished?

Conclusion

Nearly a century ago, the Benguela Railway transformed regional trade by enabling the export of copper ore from the Copperbelt of Katanga and Northern Rhodesia to Europe via the Atlantic port of Lobito. Today, the Lobito Corridor is once again a game-changer, offering a faster and more cost-effective route for shipping copper and CRMs from the Central Southern Africa region, and potentially making previously uneconomical copper ore bodies viable for extraction. But its role potentially extends beyond efficiency gains: It is now central to global decarbonisation efforts, facilitating the sourcing and transportation of CRMs with strong backing from the EU and the US.

However, the Corridor’s development is being shaped by intense geopolitical competition. China, which has significant stakes in CRM mines across the region, has simultaneously secured control over the TAZARA railway, an alternative trade route to the East African coast. This raises concerns about whether the Lobito Corridor will truly support value addition in source countries or merely serve as another avenue for resource extraction with minimal local beneficiation.

Enforcing sustainability, transparency and ethical sourcing along the Corridor remains a challenge, particularly given the presence of Chinese mining companies and artisanal miners, who are not bound by US or EU regulatory frameworks. Additionally, the political landscape in the US could impact financing commitments, as a return of the Trump presidency may curtail federal and USAID-backed support for infrastructure and value-adding activities.

Despite these uncertainties, financial commitments for the Corridor’s development have reached nearly USD 6 billion, with planned investments including upgrades to the existing railway from Lobito to Luau, redevelopment of the line from Luau to Kolwezi and construction of a new spur from Luacano to Chingola. The Lobito Corridor’s future will depend not only on these investments but also on how effectively it navigates the geopolitical tensions, ensures local benefits and upholds sustainability standards in the evolving CRM landscape.

Endnotes

[1] Critical Raw Materials (CRMs) is a contested term, as its definition varies across countries and regions, particularly between resource-producing nations and those that rely on sourcing these materials. While Global North countries have developed formal classifications of CRMs, these lists reflect strategic, economic and industrial priorities that are not universally shared. For example, the EU’s latest CRM list includes 34 materials deemed essential to its economy and technological advancement. Given these disparities, what qualifies as a CRM – and its perceived value – depends on the priorities and vulnerabilities of individual countries or regional blocs.

[2] Australia, Canada, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, India, Italy, Japan, Norway, the Republic of Korea, Sweden, the United Kingdom and the United States

About the authors

Dr. E. D. Wala Chabala

Dr. E. D. Wala Chabala is an Independent Economic Policy and Strategy Consultant and MBA Lecturer. He is a former Management Consultant at McKinsey & Company and a former Business Executive in a FTSE-100 Financial Services Company. He has also formerly been Chief Executive Officer of the Securities and Exchange Commission of Zambia.

Judy Hofmeyr

Judy Hofmeyr is a Green Transition Minerals Fellow at APRI and a University of Manchester PhD candidate leveraging extensive experience in Southern Africa's mining sector to research natural resource governance, human rights, and the socio-legal impacts of the energy transition in Africa.

This short analysis is funded by the Stiftung Mercator Foundation as part of the Geopolitics and Geoeconomics of Africa-Europe Relations Project.