Authors

Folashadé Soulé

University of Oxford

Lina Benabdallah

Wake Forest University

Cobus van Staden

China-Global South Project/SAIIA

Yunnan Chen

ODI

Yu-Shan Wu

Ocean Regions Programme

Foreword

By Elisabeth Winter, Program Director Global Markets and Social Justice, Bundeskanzler-Helmut-Schmidt-Stiftung

Olumide Abimbola, Executive Director, APRI – Africa Policy Research Institute

International narratives on a global China are diverse and even contrasting. Its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) – often seen as a synonym for China’s global ambitions – established several distinct perceptions of China. Depending on the region, an internationally assertive China is conceived as ‘global investor’, ‘equal partner’, ‘aggressor’ or ‘strategic rival’, among others. Such narratives shape our ideas and discussions. They can influence interests that spawn economic and political actions. They can serve elites and other actors as rhetorical and strategic instruments of persuasion in political decision-making processes.

The policy briefs in this report address China narratives in Africa. They stem from a conference panel organised in cooperation between the Bundeskanzler-Helmut-Schmidt-Stiftung (BKHS) and APRI - Africa Policy Research Institute. The conference panel was convened as part of a conference initiated by the BKHS on the different regional narratives on China. The conference was titled ‘From the “workshop of the world” to “systemic rival”? International perspectives on a global China’.

Together with renowned regional institutions as cooperation partners, the BKHS gathered a stellar group of distinguished international China experts from politics, academia, business and media in Hamburg in March 2023. Thanks to its truly international and interdisciplinary spirit, the conference sparked a productive conversation about the differences and similarities of the regional narratives on China in Europe, Africa, East Asia and the United States.

In Europe, China’s growing influence in Africa is often framed as a threat to ‘the West’ or even the entire continent. But, as the panel experts and authors of this report show, Africa’s China narratives are different and, most importantly, not homogeneous. The conference fostered international exchange that helped to identify the actors that construct the varying narratives, to name their motivating drivers and to better apprehend when distinct regional narratives facilitate or hinder international cooperation.

In addition to APRI, the BKHS thanks the following other cooperation partners for making the conference such a great success and hopes to witness a continued conversation on international narratives on a global China and their political implications: Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS), the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR), the German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) and the Wilson Center’s Kissinger Institute on China and the United States (KICUS).

Introduction

By Folashadé Soulé, University of Oxford

This report brings together a series of briefs questioning the importance of tracking and interrogating the role of development narratives in the context of global power shifts. Though, by focusing on the case of China–Africa relations, they question the diffusion of these narratives, they also raise more fundamental questions: Who constructs these narratives? Who is their audience? What purpose does such a diffusion serve? Is it mainly a high-level/elite project? How are these narratives pushed in the public debate?

The briefs, especially that written by Cobus van Staden, show how these narratives are taking place in a development space historically shaped by powerful Western norms. Indeed, over the years, Western-led multilateral development banks, private capital and bilateral development aid have played massive roles in the development choices of global South countries.

An example of such a narrative is the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which is woven together through a set of narratives around connectivity, South–South cooperation, new modes of development and China’s infrastructure-led development model. The country’s leaders use this narrative in their rhetoric with developing countries, which are then seduced by it and seek, at least to some extent, to emulate it. By investigating the case of the railway sector, Yunnan Chen’s brief illustrates this dynamic via the study of how China’s infrastructure finance is successfully leveraged by African states looking to fulfil goals of structural transformation and nation building via infrastructure.

Many of these narratives originate from various strategies, policy documents and outlooks. These official documents reflect the perspectives of state and regional policy elites, sometimes under the guidance of consultancy firms. These perspectives become vehicles for certain prevailing ‘objective’ narratives and speeches about how the world is structured. In this regard, Yu-Shan Wu’s brief on the construction of narratives generated about Africa’s role in the Indo-Pacific quotes the concept of ‘strategic narratives’ – a means for political actors to construct a shared meaning of international politics to shape the behaviour of domestic and international actors.

Hence, development has become a site of competition for narratives, counter-narratives and alternative narratives. In this context of global rivalries, Lina Benabdallah’s brief flips the question and asks: What are Africa’s China narratives? A survey by Afrobarometer between 2019 and mid-2021 across 34 countries showed that 62% of Africans see China’s influence in Africa as positive, similar to the 60% who said so in the case of the US. This suggests that US–China rivalry may not constitute an either-or dilemma for ordinary African citizens, but rather a win-win situation. Similarly, the data also goes against the ‘democratic backsliding’ narrative promoted by several Western powers in light of China’s growing and multifaceted engagement in Africa. Surveyed Africans considered China’s economic influence to be largely positive but also responded that they themselves largely adhere to democratic norms. This suggests a separation between welcoming China’s economic influence and an adherence to and copying of Chinese political norms and governance model, to the detriment of civil liberties.

Lina’s brief also shows the pitfalls of not recognising the non-duality of African narratives on China–Africa relations and the agency exercised by African actors in choosing their partners according to their strategic interests. Likewise, Yunnan’s brief dives into the exercise of agency by African actors despite the asymmetrical nature of their relationship. She questions how African actors have leveraged the rise of Chinese finance and Chinese contractors to meet domestic ambitions for industrial and structural transformation and how this represents a double-edged sword for African governments as they strive to achieve their domestic economic and political objectives.

Another important point that comes out of these briefs is the power of narratives and the difficulties to permanently debunk them when they are based on false allegations. Cobus van Staden’s brief mentions that, despite the high-profile debunking of the debt-trap narrative, and the fact that no other examples of Chinese seizure of collateralised state assets have been found, the narrative of Chinese ‘predatory lending’ has become a standard talking point among US, some European and even African policymakers (e.g. Nigeria).

This raises the question of the targeted audience of these narratives. To whom are they addressed? In the case of some US officials continuing to push the debt-trap narrative, we may ask: Is this narrative oriented towards their own domestic audience to show that they remain tough on China, even abroad? For example, by critically raising the risks of prevailing narratives around the Indo-Pacific, Yu-Shan’s brief reveals how these have become associated with discussions around how China can be managed as a threat or partner, detracting from underlying African concerns.

The authors’ briefs also raise deeper questions about the efficiency of narratives regarding, for instance, data security versus data sovereignty as promoted by China. Many prominent African governments have refused to engage with the data security narrative when it comes to their digital partnerships with China. In fact, the African Union renewed a contract with Huawei in 2019 for servicing the Chinese-built African Union headquarters, despite reports of regular data transfers to Shanghai in 2018.

Finally, beyond focusing on narratives as sites of power competition, it is equally important to interrogate the rise of alternative narratives and counter-narratives emerging from the global South, and with it the question of policy space. We may therefore ask: What are Africa’s policy space and policy options in this context of global rivalries? Are alternative narratives emanating from the global South the solution for more autonomy and ‘non-alignment’, in the sense of carving an autonomous foreign policy despite the asymmetrical nature of the relationship with China?

1.

Going beyond binary narratives of China–Africa relations

By Lina Benabdallah, Wake Forest University

Dominant binary narratives about African perceptions of US–China rivalry

During the Munich Security Conference of 2023, Ghanaian President Nana Akufo-Addo remarked: ‘if we indeed have cooperation between the South and the North, the fundamental requirement of solidarity in the political world is to overcome the “them and us”’. 1 This narrative of ‘them and us’ is one that expands to representations of Euro-American interests sitting necessarily at odds with China’s when it comes to engaging the African continent. Indeed, one of the most salient narratives about US–Africa–China relations found across mainstream media narratives and policy circles is that there is a zero-sum game rivalry between the US and China in Africa. However, binary interpretations of US–China rivalry in Africa leave very little room for nuance or for Africans to be included as agents representing their sovereign interests. Accordingly, this brief argues that binary narratives of China’s influence in Africa being good vs evil, benign vs neocolonial, friendly vs exploitative, and so on are not productive. Instead, taking African perspectives seriously necessitates going beyond the simplistic binary thinking. This means recognising that almost all aspects of China–Africa relations – the positive and negative, the strategic and organic, the opportunity and challenge – sit side by side.

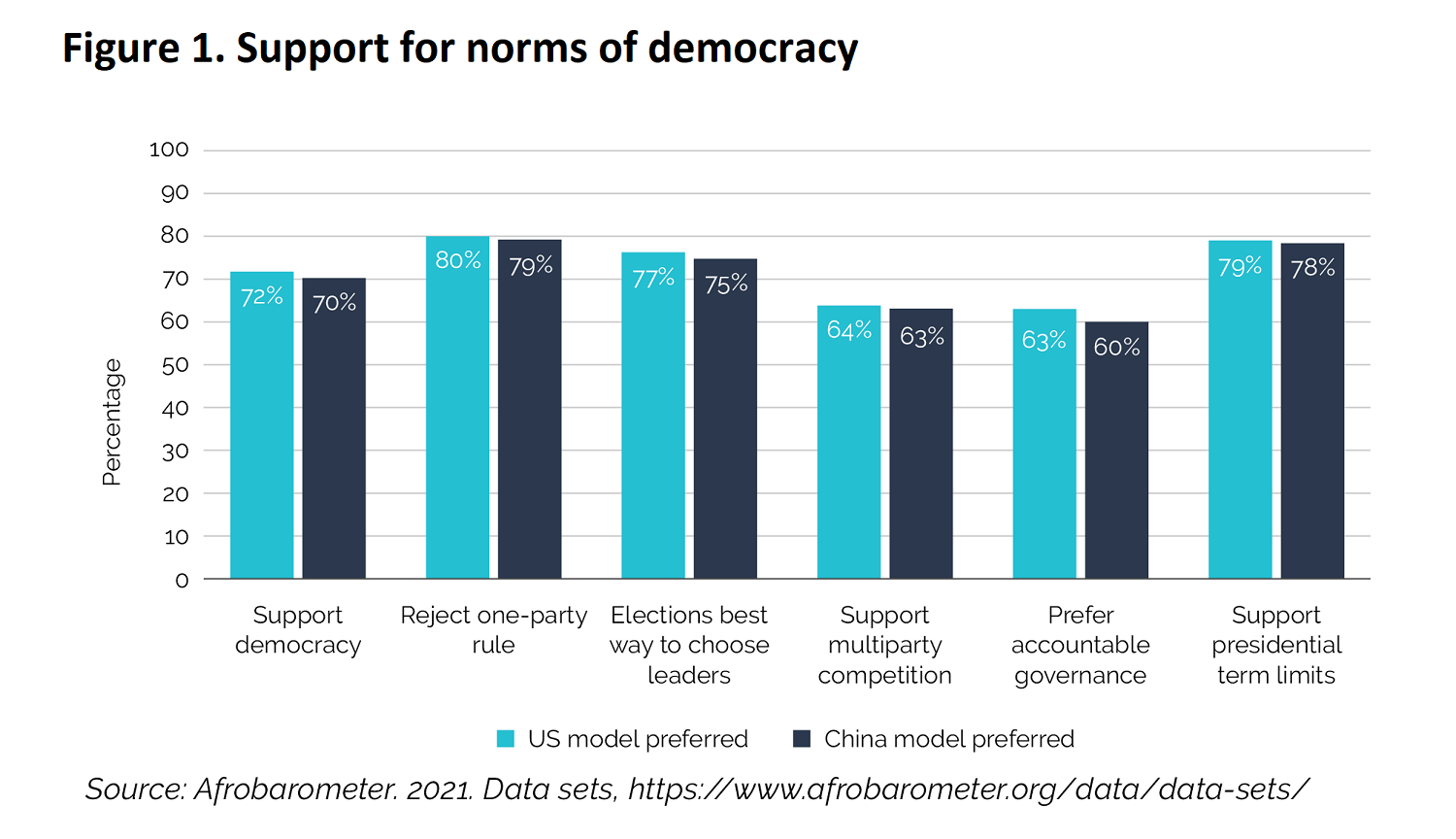

One of the main data points illustrating this argument comes from Afrobarometer surveys. 2 As Afrobarometer shows, approximately the same number of surveyed Africans think that China and the US have equal potential as beneficial partners and viable development models. Furthermore, from Figure 1, we can see that 70% of surveyed Africans who expressed preference for the China model were in favour of democracy. This is against a very close 72% who expressed preference for the US model. The vast majority of Africans also reject one-party rule, support presidential term limits, and find elections to be the best way to choose leaders. This suggests that thinking that China’s development model is attractive does not simply mean that Africans are not choosing norms of democracy and competitive elections. In fact, by looking at the data, it becomes evident that a binary narrative of either China or democracy or either the US or China is not a very helpful framework to understand narratives on China from the African perspective.

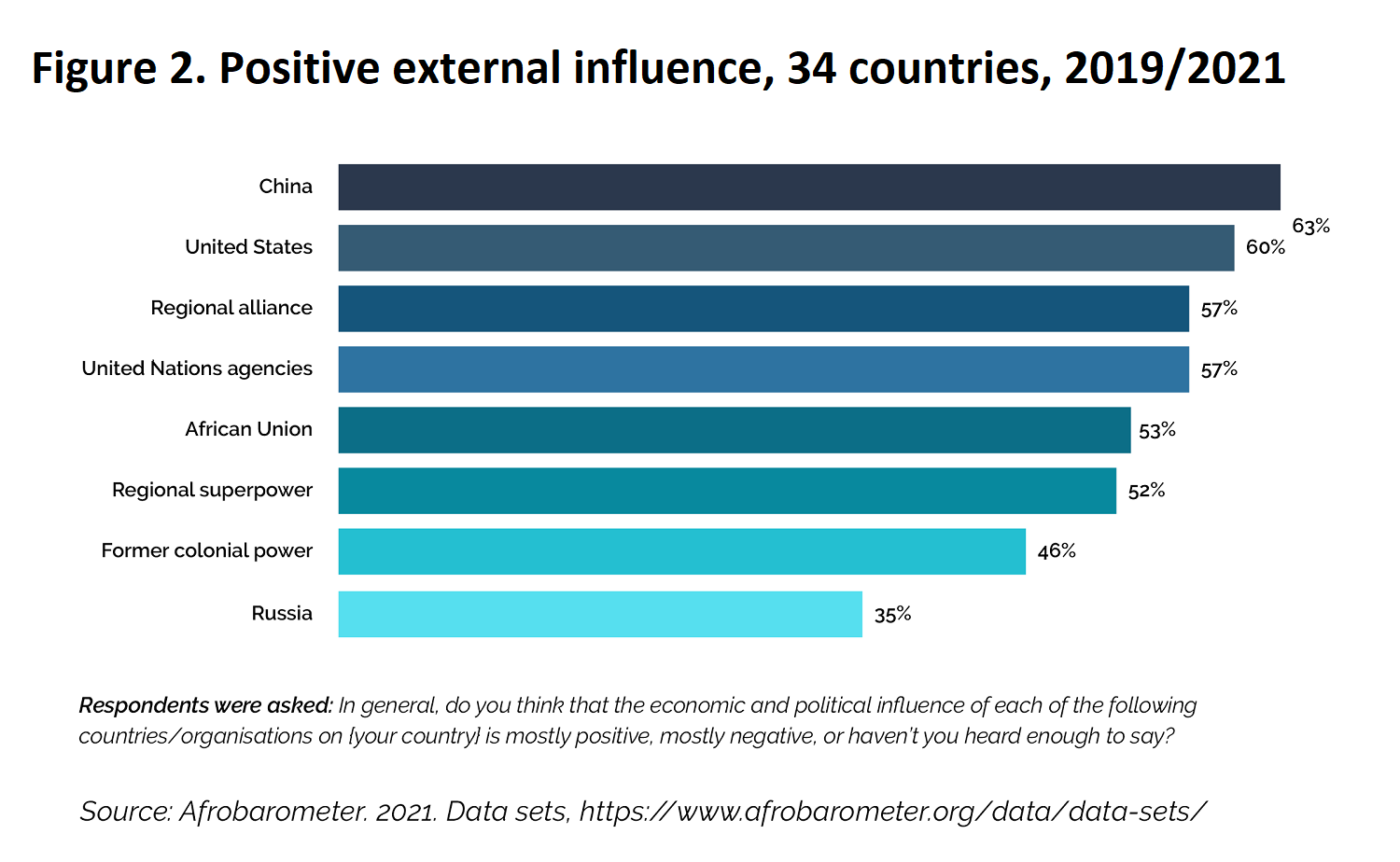

In much the same way, according to Afrobarometer surveys conducted in 2021, 63% of surveyed Africans identified China’s economic and political influence as positive, against 60% of collected responses identifying the US as a positive model. This shows that the US and China are not viewed in a zero-sum way by Africans. To be sure, the results vary country by country, but by and large they show that the difference is not significant, and that Africans felt able to find positive qualities in each of the two models (Figure 2).

Pitfalls of binary narratives on China–Africa relations

Some scholars and experts insist that, since there is a power imbalance between China and most African countries and China clearly overpowers most countries in Africa and the global South, African perspectives matter only insofar as they have affinity with China’s core interests. These interests are defined according to national security priorities and goals set by Chinese policymakers to safeguard China’s domestic interests as well as its international ambitions. This somewhat cynical though perhaps realist lens through which one may analyse African narratives attributes very little agency or significance to what Africans want or do not want. In this view, these wants and needs are secondary to what China’s core interests dictate. Of course, such views do not centre African narratives; they assume a power politics framework where smaller states ‘must suffer what they must’.

There are several issues with such a narrative. In these scenarios, Africans are just passive actors going with the flow, gaining infrastructure deals when they fit China’s goals, benefitting from debt write-offs on Beijing’s terms rather than from the demand side, and so on. Any opposition to Beijing is understood as an irrational behaviour that could cost a country its share of precious Chinese investments. In effect, these narratives assume Africans to be incapable of making their own decisions about their development paths, their preferred partners or their business cultures, which might be different from that of the West. Following a colonial mindset, these narratives discount Africans as being far from independent, responsible and proactive agents 3 and instead paint them as being exploited by a malign China (see for instance the debt-trap narrative 4). A concrete example of the implications of these simplistic narratives is the resolution undertaken by US congress to denounce (and shame) South Africa 5 for its joint naval exercise with China and Russia. The resolution calls on the US president to ‘do something about this’, ignoring the fact that such action would effectively constitute interference in the sovereign matters of an independent country.

Rather than understanding China–Africa relations through a realist lens where material and military power (of China) dictates the outcome (for Africans), it is more productive to look past the dualities of binary thinking and unpack African narratives about China–Africa relations.

African narratives on China: Global, multilateral and bilateral perspectives

In this section I provide some of the salient narratives that Africans and the African Union (AU) present about China–Africa relations. Caveating the issue of putting an entire continent on one side and one country on the other, these themes can be grouped into three categories: 1) African narratives about China from a global perspective; 2) African narratives about China from a multilateral perspective; and 3) African narratives about China from a bilateral perspective.

On a global level, Africans view China as an alternative rising power that can offer a way out of Western-led liberal order institutions (which are viewed as extractive and unjust), and a potential means of levelling the playing field against US hegemony. Taking the view of China as an alternative does not imply that Africans are entering into a holistic alliance with China. Instead, what we see is strategic alignment on matters of shared interests. Furthermore, pre-dating the New Silk Road, Mao’s regime and the early years of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) were an example of global South solidarity where Beijing offered a viable alternative providing support for the revolutionary wars sparking across the continent.

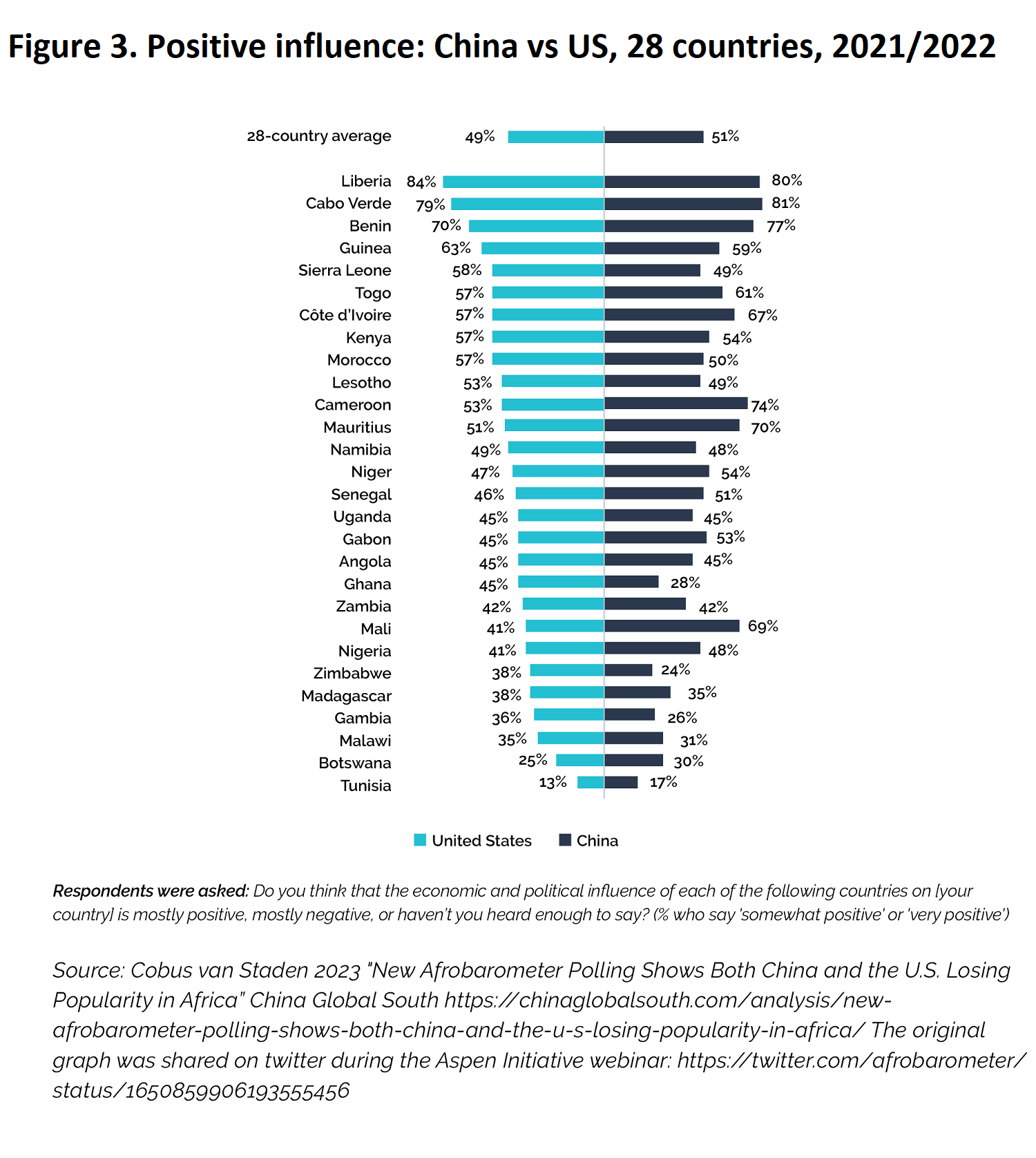

During the Cold War, the PRC spearheaded a third path apart from picking sides between the US and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). Therefore, from an African perspective, relations with China often present a much-needed alternative. In terms of infrastructure financing, lending and other initiatives, the PRC also stepped in for Africans at a time when, during the 2008 financial crisis, European economies were turning inwards, and some had waves of right-wing politics that saw their interests shift away from the global South. During that momentum loss, Beijing increasingly grew its influence and visibility in Africa. To be sure, thinking of China as an alternative does not mean that Africans view diplomatic ties with the US as unimportant. As Figure 3 indicates, approximately the same number of surveyed Africans who think China’s influence in their country is positive, also think the same of the US.

On a multilateral level, Africans view China as a partner they can turn to for a variety of services, deals and initiatives for which traditional partners turn them down or agree only on rigid terms and instruction. For the AU, China is a partner that takes regional and multilateral organisations on the continent seriously. Since the AU gained a member seat at the Forum on China–Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) in 2012, it has worked on finding areas of alignment with China’s own development plans. For instance, at the latest edition of FOCAC, which was hosted in Dakar, the AU harmonised its Agenda 2063 with China’s development goals through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and other measures. Relatedly, Beijing is also increasingly viewed as a viable mediation partner 6 that is both willing and able to play a constructive role remedying internal conflicts on the continent. Examples of China playing such a role include recent mediations over the conflict in Tigray, mediation between Sudan, Egypt and Ethiopia over the Nile, in Sudan during the Darfur crisis in 2008, and so on.

On a bilateral level, the diverse array of African narratives on China is most prominent. Since each country is different, we have seen reactions vary from ideological alignment with Beijing’s position to overt criticism – from countries with robust civil society organisations – of Chinese mining activities regarding, for instance, the impacts of megastructures and infrastructure on the environment, issues of labour practices, and opaque BRI contracts that conceal from the public what assets are written off as collateral damage in case countries default on their debt payments to Beijing. We also see, at the level of bilateral relations, a group of African countries that take China’s development model (however contested this notion is from the Chinese side) as an example for their own growth (the case of Ethiopia is by now relatively well known). While there are more varieties of narratives, it is at the level of bilateral relations that we see the most striking examples of, for example, difference, unconformity, competition with China, competition for Chinese funding, and leveraging Chinese funding to get better deals with Western partners.

Going beyond binary narratives when analysing China–Africa relations permits us to see the nuance and divergence of perceptions, interests and pursuits that Africans follow in their relations with Beijing. The African continent is diverse and reactions to Chinese investments necessarily vary not only by state but also by different groups of elites, civil society organisations, activists and so on.

2.

Debt traps and other stories: The Western counter-narration of Africa–China relations

By Cobus van Staden, China-Global South Project/SAIIA

Introduction

The rise of Western anxiety about how China’s rise is triggering a changing global order has coincided with the rapid increase in narratives about the nature and effect of China’s growing power. Africa– China narratives have played an important role in this process, not least due to Africa’s continued status as an object of Western narratives that reveal much about how the stark inequities between African and Western power are justified, normalised and turned into self-flattering stories about Western power itself.

In this policy brief, I put this trend in the context of a rising China’s challenge to Western self-narration. I show that narratives of development play a key role in justifying Western leadership, and that Chinese developmental counter-narratives represent a challenge to this claim. I then focus on a current example of such narrative contestation: the debt-trap narrative.

Background: Development narratives

The focus on the role of narrative in Africa–China relations should first be contextualised against the long history of Western self-narration in relation to development. Because I lack the space to unpack this complex history here, I will only note that Africa has played an unwilling but central role in this history. Africa has frequently been dragooned into an unflattering binary opposition, where it was made to represent lack or absence in contrast to a narrative of European plenitude. Whereas Europe was the ‘light’ in Enlightenment, Africa was the ‘Dark Continent’. African people and societies were frequently described as anti-rational, anti-scientific, ahistorical and strangers to literacy and writing. In contrast, Euro-American societies were presented as not only having achieved development, but providing the only credible roadmap to it.

This metanarrative facilitated colonialism. After the colonial era, it remained in the narrative scaffolding that underpinned postcolonial thinking on development, especially after the Cold War, when competing Soviet narratives fell away. Key among these Western narratives were a focus on civil and political rights (rather than socioeconomic rights), parliamentary democracy, free markets and independent institutions.

The window from the end of the Cold War to the global economic crisis of 2008 was a particularly intense period of Western leadership, which saw discursive shifts within Western-led institutions (for example from funding hard infrastructure towards supporting soft infrastructure via civil society support) reshape the development options of the global South.

It was during this era that China rose to become the world’s second-largest economy. On the one hand, China’s rapid development was immeasurably aided by traditional development partners, as well as Western public and private sector actors. On the other hand, China’s rise provided a fundamental set of challenges to core Western narratives of development, such as the centrality of democracy to development.

China has long maintained its own set of narratives that underlie its relationship with the global South. Key among these was China’s experiences under external imperialism, and its support for decolonial struggles during the twentieth century. Its rapid rise added a robust developmental narrative to this arsenal. This happened as the coherence of Western narratives of development and governance were shaken by successive crises and challenges, notably the invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan, the global financial crisis, the rise of Trumpism, Brexit, the Black Lives Matter movement, the Covid-19 pandemic, and the wars in Ukraine and Gaza.

China has used its own development trajectory as part of a series of counter-narratives that challenge those from the West. First, its development narrative is highly state- and party-centric. It emphasises central planning and a close relationship between the state, the party and the private sector. Further, as mentioned above, it challenges the centrality of democracy to development. It especially decentres civil and political rights in favour of collective and socioeconomic rights. In addition, it makes the case for a collective right to development (with a core role for the state without binding it to liberal values) – a narrative Western powers have resisted, due, in part, to concerns about state overreach. 7

China has bolstered the impact of this narrative through a series of global initiatives which are frequently lent coherence via narrative. The most famous of these is the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). While extremely vague in definition and often chaotic in implementation, the BRI is woven together through a set of narratives around connectivity, South–South cooperation and new modes of development. The BRI has since generated its own set of narratives around digital, health and space connectivity, while also being joined by subsequent initiatives, notably the Global Development Initiative, the Global Security Initiative, the Global Civilization Initiative, and emerging discourse around shared human values (as opposed to Western rights conceptions), as recently seen at China’s Second International Forum on Democracy. 8

China is thus increasingly emphasising its own development trajectory as an alternative to the EuroAmerican model. In April 2023, the National Development and Reform Commission stated: ‘[T]he Chinese path to modernization is the only correct way toward national rejuvenation. This pathway breaks the myth that modernization equals Westernization and displays a different vision for modernization, expanding the choices for developing countries in their modernization journey.’ 9 In addition to simply challenging the uniqueness ascribed to the Western modernisation narrative, Chinese officials also argue that, unlike Western modernisation, ‘Chinese modernization is not pursued through war, colonization or exploitation’. 10

Counter-narration

Western powers have responded to the rise of China through a set of broad counter-narratives. These include drawing a rhetorical line between democracies and autocracies and emphasising the centrality of ‘values’ in Western approaches to development.

In the case of Africa and the wider postcolonial world, these have dovetailed with more pointed narratives aimed at China’s rapid rise as a financier and builder of infrastructure in the global South. Growing global awareness of Africa–China relations has overlapped with the growing prominence of narratives around the quality of Chinese infrastructure, the importation of Chinese workers, and, perhaps most prominently, narratives about the malign influence of Chinese lending to African countries. The most prominent example of these came to be known as the debt-trap narrative.

In short, the debt-trap narrative alleges that China deliberately mires small countries in unsustainable debt in order to seize state assets as collateral when the borrower inevitably defaults. The debt-trap concept was reputedly coined by Brahma Chellaney, an Indian author, and a professor of strategic studies at the Center for Policy Research in New Delhi. 11 The narrative gained prominence in the US after a paper by two graduate students, Sam Parker and Gabrielle Chefitz, was published by Harvard’s Kennedy School of Governance’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. 12 The paper alleged that a 99-year lease agreement with China Merchants Port Holdings for the use of Sri Lanka’s Hambantota Port was an example of an asset seizure engineered as part of a Chinese debt trap. The paper linked the seizure to three supposed Chinese strategic goals in the region: setting up a ‘string of pearls’ of ports to project control over South Asian shipping routes, strengthening claims over territory in the South China Sea, and expanding power deeper into the Pacific.

Despite attempts by journalists to find other examples of debt-trap-related asset seizures, the narrative remained linked to Hambantota Port. This link was strengthened by intensive US coverage, prominent among which was a New York Times article from June 2018 entitled ‘How China got Sri Lanka to cough up a port’. 13 This and related reporting firmly sealed the narrative link between China, Sri Lanka, Hambantota and the debt trap. It soon became a standard talking point among Trump administration officials, with former secretaries of state Rex Tillerson and Mike Pompeo, and national security advisor John Bolton becoming prominent advocates of the narrative, linking it to the greater BRI.

In response, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokespeople accused Pompeo of lying, with then-spokesperson Zhao Lijian calling the charge a smear attack. 14 Meanwhile, several researchers debunked the Hambantota accusation. Notably, the head of Johns Hopkins University’s China–Africa Research Initiative, Deborah Brautigam, published a series of articles and op-eds showing that the Hambantota deal was not a debt-for-equity swap. Rather, the proceeds from the deal were used by the Sri Lankan government to deal with other loans, and the Hambantota debt still must be paid off. 15 Despite the high-profile debunking, and the fact that no other examples of Chinese seizure of collateralised state assets have been found, the narrative of Chinese ‘predatory lending’ has become a standard talking point among US policymakers. For example, at the Americas Partnership for Economic Prosperity Leaders’ Summit in November 2023, US President Joe Biden told South American leaders: ‘I want to make sure that our closest neighbors know they have a real choice between debt-trap diplomacy and high-quality transparent approaches to infrastructure and to development.’ 16

In her critique of the debt-trap narrative, Brautigam characterised it as a meme. The word ‘meme’ was originally coined by Richard Dawkins to mean the intellectual equivalent of a gene, capable of independent mutation as part of Darwinian competition. In a 2013 interview he complained that this aspect of independent mutation was lost when the concept was appropriated to refer to the spread of digital pop culture artefacts on social media channels, as each specific iteration of a meme also reflects a creative intervention by an individual user. 17 This suggests Dawkins would reject Brautigan’s characterisation in this instance, as would I, though for a different reason: rather than reflecting the flat hierarchy of social media, I would argue that it is more accurate to think of the debt trap as a form of state-directed narrative disinformation, specifically targeting global South elites.

In this respect, the narrative has been remarkably successful. For example, in 2022, the Ugandan legislature held hearings into a loan agreement with China Exim Bank for the expansion of Entebbe Airport. 18 The hearings were dominated by concern that the airport would be seized as collateral, whipped up by extensive media repetition of the debt-trap narrative, including a much watched (and factually inaccurate) Daily Show segment. 19

The seizure issue dominated the hearings, even though such a seizure never formed part of the original contract. Meanwhile, other highly problematic aspects of the contract, including provisions that would force the revenue from the airport to be put into an escrow account that would enable the preferential repayment of the Chinese loan ahead of other loans, and a stipulation that would force arbitration around the loan to take place in China, received very little attention.

More broadly, the debt-trap narrative has had the effect of masking the continued centrality of Western power in a growing African debt crisis. For example, Linda Thomas-Greenfield, currently the US ambassador to the United Nations (UN), remarked to Bloomberg in February 2023 that the US and its allies, as part of the Highly Indebted Poor Country (HIPC) initiative, ‘worked to help African countries address their debt issues, and China has come in and re-indebted these countries’. 20

These narratives have found anxious audiences in Africa. For example, Nigerian policymakers have raised the potential risks of asset seizures in relation to Chinese debt, even though this debt only makes up 3.8% of the country’s total debt load. 21 This glossed over the fact that Nigeria’s debt to Western-led multilateral development banks (MDBs) and holders of Eurobonds and other forms of Western-held private sector debt are considerably larger than its debt to China. 22

The International Monetary Fund has confirmed that, except for a few outliers like Angola, Western MDBs and private lenders hold the vast majority of African debt. 23 This is in part due to a retreat of bilateral lending by Western governments after the global financial crisis, which coincided with Western private capital turning to global South markets due to low interest rates at home. The Covid and Ukraine crises (and their attendant interest rate hikes) have helped to push these countries closer to the edge. 24

Conclusion

The debt-trap narrative has come to function as a deflection of wider global dissatisfaction with the continued Western centrality within the Bretton Woods institutions. China complicates the continued Western centrality within these institutions, as well as their continued global dominance, through attempts to change their shareholder structure. Moreover, Chinese lending has almost equalled that of the World Bank, further tipping the balance of power.

Development narratives are key to Western powers’ ability to set norms and shape intellectual horizons around the world. They provide an important justification of Western leadership, so that the questioning of Western norms is akin to questioning development itself. China’s rolling out of counter-narratives of Chinese modernisation is a notable challenge to this attempted hegemony. I would argue that the longevity of the debt-trap narrative among Western policymakers, despite its debunking, illustrates Western anxieties about this challenge.

3.

Borrowing for belts and roads: The double edge of China’s infrastructure lending in Africa

By Yunnan Chen, ODI

The rise of China in Africa over the last two decades can be seen on the skyline: where Chinese construction contractors, technologies and finance have shaped the architecture of African cities and the contours of its road and rail networks. This brief dives into the landscape of Chinese infrastructure investment in Africa, and asks the following: How has China’s presence shaped narratives on the African continent? What do these narratives reveal, and how have they been instrumentalised?

Chinese finance and Chinese contractors have been critical in the construction and implementation of new infrastructures, and have been harnessed by African sovereigns to meet domestic ambitions for industrial and structural transformation. At the same time, this remains a relationship of profound asymmetry. The indebtedness that has come with financing infrastructure investment has led to an emerging (and hyperbolic) narrative of ‘debt traps’, 25 which perpetuates a misconceived perception of African states as passive victims, while Chinese narratives on the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and China–Africa friendship obscure the flaws and real challenges on the ground. The reality is more ambivalent. African narratives on China have been buried amid duelling discourses, but show a clear-eyed recognition of China’s advantages as a partner, and the real asymmetry of global structural inequalities. For partners in Europe and the global North, it is critical to listen to narratives from African states and society while reshaping their own, to recognise African agency, and to view Africa for its intrinsic opportunities, rather than in instrumental terms.

Infrastructure finance and the BRI in Africa

In the years following the global financial crisis, China’s overseas financing began to grow. This ripple outward was a direct consequence of its domestic economic investment, which saw a growing overcapacity and saturation in infrastructure markets at home. Supported by China’s major policy banks, this internationalisation of Chinese capital and Chinese companies eventually coalesced in 2013 under the label of the BRI. Data on China’s overseas financing in Africa shows that it peaked in the mid-2010s, during a golden era when African economies were fast-growing, fuelled in part by buoyant commodity prices and low global interest rates that supported external access to capital.

As a narrative, the BRI has been perhaps the most successful and salient in China’s public diplomacy. Though viewed with suspicion by Western observers as an emanation of China’s ‘grand strategy’ in Eurasia, 26 the BRI has been much more fluid and flexible. The BRI was integrated into pre-existing frameworks of China–Africa cooperation, including the Forum on China–Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), and memorandums of understanding (MOUs) signed with China on BRI cooperation have proliferated across the African continent. The BRI’s focus on connectivity infrastructure and associated financing drove a narrative of China as a provider of global public goods through infrastructure finance, promoting trade and integration over isolationism. 27

On the other side, African economies have been key markets for infrastructure construction and investment, particularly in transport (roads, railways and port projects). Within China’s official committed lending to Africa, transport constituted under 30% of total committed lending from official creditors between 2000–2019, and transport and energy together just over 50%. Prominent flagship infrastructure projects including ports and Standard Gauge Railways (SGRs) in Kenya and Ethiopia, whose construction pre-dated the announcement of the BRI, were also folded into the initiative as case examples of the BRI’s impact on connectivity, trade and economic development. 28

These offers of infrastructure packages with favourable, fast financing also aligned with African narratives of modernisation and development. African sovereigns have leveraged Chinese financial and technical resources to achieve developmental and political objectives. In Ethiopia, the development of a national railway network served as a form of nation building. The SGR in particular was sold with a promise of modernisation – it would be a modern transport system that would reinforce the legitimacy of the ruling party and its model of a developmental state. 29 Likewise, the Kenyan SGR was leveraged by domestic political actors for electoral gain in terms of the timing of its inauguration. The speed of Chinese construction contractors was a boon in serving domestic patronage systems. 30 It has also tied into grander narratives of nationalism – most explicitly embodied in the name the ‘Madaraka Express’, or ‘freedom’ railway, as well as becoming a flagship embodiment of win-win Sino-Africa cooperation and the BRI in Africa, despite the problematic financing and operational issues that the project has been beset with since its commission. 31

Debt in the age of geopolitics

Over the past decade, Chinese infrastructure finance and its presence in Africa has also drawn growing criticism. Much of this has concerned the quality of projects, grievances over Chinese labour practices, 32 and the contribution to local corruption. 33 In recent years, the most endemic narrative against China’s infrastructure finance and the BRI has been the ‘debt-trap diplomacy’, first cited by an Indian scholar, and then popularised by US policymakers and media outlets increasingly hawkish on China’s presence in the global South. 34 Sri Lanka’s Hambantota Port has been the prime case study that set off alarms. 35 Other infrastructure projects, including Entebbe Airport in Uganda, and the port in Mombasa, Kenya, have also generated controversy over perceived Chinese takeovers of infrastructure assets. 36

None of the evidence for these cases has stood up to scrutiny: while Chinese lenders do use project operational revenues as a form of collateral and a security against default, there has never been a publicised, verified case of asset seizure or coercive takeover. 37 Nevertheless, as bilateral relations have deteriorated, the narrative of China’s ‘predatory lending’ in Africa has become a narrative weaponised primarily by US policymakers criticising China’s influence in Africa and the global South.

Following the systemic shock of Covid-19, the war in Ukraine and rising interest rates globally, all of this has compounded into a polycrisis for indebted sovereigns in Africa and the global South. The current debt crisis in certain African economies has intensified a bout of finger-pointing at Chinese lenders for contributing to African debt burdens and loading African sovereigns with unsustainable debt, and to China’s recalcitrance in renegotiations on debt restructuring.

‘When two elephants fight, the grass gets trampled’ has been a recurrent saying in describing the impacts of US–China rivalry for African debt negotiations. The case of Zambia has been a clear and painful example of this. Zambia was the first country to default during the Covid-19 pandemic in 2021, and was the first country to sign up to the G20 Common Framework for Debt Treatments beyond the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI). It became the first test case for a multilateral framework for debt restructuring, designed to ensure equal treatment for all creditors, official bilaterals and private sector creditors.

However, it took two years from joining the Common Framework for Zambia’s creditor committee to agree to a debt relief and restructuring plan. To date, Zambia’s debt negotiations remain protracted around both technical deliberations such as debt sustainability analyses, and bargaining around the comparability of treatment between official and commercial creditors and bondholders. However, the process was also hindered by political finger-pointing, as the US criticised China as a ‘barrier’ to negotiations, while China blamed the US for its own domestic debt problems and interest rate hikes that were ‘sabotaging other sovereign countries’ active efforts to solve their debt issues'. 38 The ramifications of geopoliticising debt have deepened tensions and further prolonged negotiations, to the cost of Zambia’s economy and society.

Situating African agency in debt and lending

The proliferation of debt-trap narratives and accusations of predatory lending has certainly contributed to greater scrutiny of, and demand for, accountability in African societies. The focus has been on governance of infrastructure projects and external borrowing, as in the case of Kenya’s SGR, which has seen growing criticism of the opacity of external borrowing.

However, there has been relatively muted critique of Chinese lending from African elites and leaders. The debt-trap narrative is not one that is shared by African sovereigns. Indeed, outside of the case of Zambia, other countries that have borrowed heavily from China, such as Ethiopia and Angola, have been able to leverage flexibility on the part of Chinese creditors. Angola, a participant of the DSSI, was a quiet success case of bilateral negotiation, and was able to restructure a major portion of its loans with two large Chinese creditors. 39 In the case of Ethiopia, at the end of 2018 (prior to joining the DSSI during Covid), the government was able to restructure the maturity terms on its railway loan with China Exim Bank through a significant concession. This was accomplished following a series of high-level meetings between Ethiopian and Chinese leaders after the FOCAC summit. Even before 2018, Ethiopia was allowed to defer repayments for nearly a year, giving it fiscal breathing space – even as it continued to repay bondholders and private creditors.

Rather than seeing a ‘debt trap’, Ethiopian elites, for example, observe that with respect to commercial, private creditors, Chinese creditors have been far more collaborative, flexible and ‘willing to work with you’ in times of difficulty. 40 Chinese capital, in support of Chinese infrastructure construction in Africa, also filled a vacuum when, throughout the 1990s and 2000s, multilateral and bilateral donors retreated from large projects in the infrastructure sector due to perceptions of high risks of social and environmental impacts, as well as risks related to finance and projects. Resisting the Sinophobic narrative that has largely been pushed by Western media, African elites and popular society largely take a pragmatic, even positive view on China. They recognise Western-driven narratives as deliberately divisive, and also value the concrete financing and development benefits, as well as the policy autonomy, that the expansion of Chinese financing has brought. 41 Afrobarometer surveys show China with the highest percentage score (63%) for ‘positive external influence’, above the US and other former colonial powers. 42

However, while positive, these measures of support have declined in recent years in the wake of incidents of racial discrimination against Africans in China during Covid-19. 43 A growing backlash against cases of corruption and opacity in contracts for Chinese projects and financing has also contributed to wider ambivalence towards China within African populations. 44 While debt traps may be a myth, there are real issues with practices in the uses of collateral and a lack of transparency around Chinese contracting and financing practices that do not work in the interests of African borrowers. 45

There is still a fundamental need for capacity to increase autonomy in bargaining with external actors and financiers – whether Chinese or commercial bondholders – and to reduce the vulnerability that comes with dependence on external financing. Supporting domestic investment and financing resources, and the formation of domestic capital markets, should be a mutual interest for African states and those concerned about the risks of unsustainable debt.

Countering China? Implications for global development cooperation

With the rise of the European Union’s (EU) Global Gateway and the G7 Partnership for Global Infrastructure Investment (PGII), which, since 2021, have undergirded much of the EU and G7 partners’ development strategies in the global South, the rise of the BRI has spurred a new competition around narratives of infrastructure development. In particular, since 2019, Europe, under Ursula von der Leyen, has taken a new geopolitical focus in its engagement with Africa; 46 funding for Africa will occupy the majority of Europe’s financing commitments under the Global Gateway. 47

Competition can expand African choice and agency in terms of partners and potential new resources for development, particularly those sustaining infrastructure investment needs. However, the underlying focus of geopolitical competition that drives these new initiatives continues to position Africa in instrumental terms, as a site of competition for influence, or in terms of Europe’s own security and strategic interests, rather than in intrinsic terms as a site of opportunity or market potential. 48 Official financing and official development assistance (ODA) are strategic levers to mobilise private sector investment into Africa and the global South, yet how effectively this can ameliorate commercial risk perceptions of Africa remains to be seen. Another danger is that as Chinese interests in Africa shift and wane given decreased risk appetites in overseas finance since 2018, the reduction or removal of competition as a strategic goal may also see a similar fading of Africa in European or G7 priorities. 49

Narratives around China in Africa remain driven by the media and actors of the global North. However, attitudes and expressions of African society and sovereigns themselves are more clear-eyed and pragmatic: Africa values both the concrete advantages of Chinese cooperation, and the strategic autonomy of working with multiple partners and providers beyond China. Development partners and development finance institutions should therefore be wary of using development instruments as part of a wider geopolitical cold war, and recognise the importance of credibility and consistency as a force for power and influence. 50 The 2024 FOCAC will underline a new phase of China–Africa cooperation and will constitute an opportunity for African actors to shape their relations with China – to sustain Chinese economic interests in Africa in the wake of a changed global economy, and demonstrate to the wider world Africa’s ability to shape its interests with global powers, even in the context of asymmetry.

4.

What the Indo-Pacific narrative tells us about China and Africa

By Yu-Shan Wu, Ocean Regions Programme

Narratives – that is, how events and facts are threaded together – matter in an information age. This is particularly true in a post-truth era, where policymakers and politicians such as former US president Donald Trump have actively taken to social media platforms to promote particular narratives. 51 It is also the emotive appeal of certain narratives that has distilled reporting on China’s relations with Africa as either a threat or a benevolent partner. 52

This brief explores the Indo-Pacific narrative that recognises the interconnectedness of the Indian and Pacific oceans, and expands (and for some, replaces) the Asia-Pacific concept. 53 As a foreign policy idea, the Indo-Pacific adds a layer to the discussion on narratives beyond media reporting, as views about the world are also perpetuated and promoted through official policy documents. To date, the Indo-Pacific has been largely applied by the US and its partners and this leaves gaps, especially for those who are unevenly accounted for in its geographic delineations. The question, then, is how Africa fits into the dominating as well as counter-narratives surrounding the Indo-Pacific. Such a counter-narrative to the Indo-Pacific is China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in Africa.

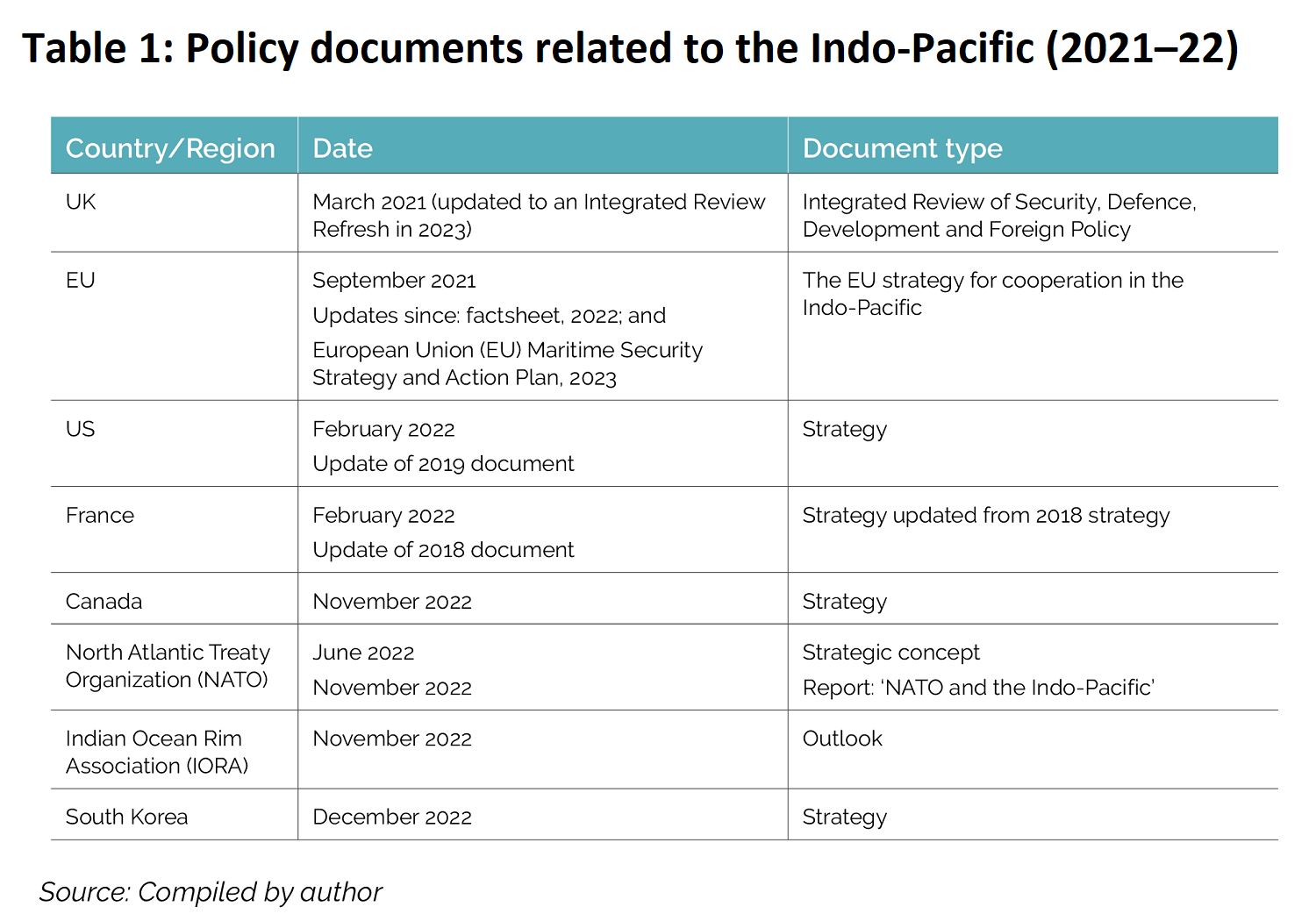

Roughly 65% of the world’s population and three of four of the world’s largest economies outside of Europe (China, India and Japan) are in the Indo-Pacific. Since 2007, the US and its partners – such as Australia, India and Japan, who together make up the Quad – have promoted the Indo-Pacific concept through statements, defence white papers and strategies. 54 The concept continues to be promoted. In fact, between 2021 and 2022, eight new policy documents were published (Table 1). Notably, as of mid-2023, states such as Japan 55 and the United Kingdom (UK) 56 further updated and recommitted their positions towards this mega-region.

The policy documents represent a collection of views on how the world is structured and geographically organised. There are of course variations. For example, the intergovernmental organisation IORA labels its document an ‘outlook’ – which resonates with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations' (ASEAN) 2019 outlook – and unlike the other strategies that represent action documents, it emphasises guiding principles and ideas as a foundation for engagement in the evolving Indo-Pacific. 57

The Indo-Pacific in relation to China and Africa

When looking at the strategies released between 2021 and 2022, it is striking that neither China nor any African state has developed a policy towards the Indo-Pacific. Yet two aspects, one related to China and the other to Africa, stand out in relation to the discussion on narratives.

The first is that China does not actually subscribe to the Indo-Pacific concept and is commonly identified in the strategies as a threat or challenge. 58 The US 2022 strategy identifies China as a threat, ahead of climate change, and this sentiment is echoed by Canada, the EU (although it should be noted that state positions vary) and NATO (an alliance of European and North American states). Several strategies even call China a ‘systemic challenge’, a ‘strategic competitor’ or ‘disruptive global power’. It appears that the Indo-Pacific provides a shared foundation for American and European understanding in responding to China. This contrasts with more moderate positions such as South Korea’s strategy and those of the intergovernmental bodies mentioned.

The second aspect relates to the geographic scope of the Indo-Pacific. Beyond India, the westernmost part of the Indian Ocean, namely African islands and littoral states, remains unevenly accounted for in the strategies of 2021–2022 (although the continent has been included in previous state approaches, such as those of India and Japan). 59 Africa is not mentioned in the US strategy and while it is mentioned by Canada and NATO, the continent is viewed largely as a part of China’s and Russia’s growing influence.

The qualitative absence of African partners is due to the fact that most strategies locate the Pacific – for example the Taiwan Strait, India–China border, Korean Peninsula and South China Sea – as the centre of global tensions. Amid the Russia–Ukraine War, and Russia’s relatively close ties with China that extend European concerns into the Indo-Pacific, there is also hope that other powers in the mega-region can play a role in upholding the current rules-based international system. 60 There have, however, been attempts to shift the Indo-Pacific from a strategic concept 61 to include wider issues (see the recent Quad leaders’ meeting). 62 Nevertheless, more weight is still given to security than to economic concerns.

In order for the Indo-Pacific narrative to find resonance in Africa, there also needs to be an emphasis on non-traditional security concerns such as combating piracy, rising sea levels and overfishing 63 that dominate in the Indian Ocean. These concerns stand in contrast to the geopolitical tensions in the Pacific Ocean.

Implications of the Indo-Pacific narrative for Africa

The Indo-Pacific, as a concept, is still evolving. Therefore, the interpretations as set out by the various strategies are significant. The narratives in the strategies are an articulation of state and policy elites’ interests and their view of the world; these documents are essentially a means to conceptualise a complex world. This suggests that geography is not simply factual or physical but informed by assumptions, perceptions and ideas of what is included and what is not. 64 Mapping thus involves a mental landscape too. 65 For instance, several of the strategies and outlooks – as documents in the public sphere – have identified the Indo-Pacific as a central theatre where competition is playing out (although within this space approaches may differ depending on whether China is regarded as a threat or if there is a sense that the wider US–China rivalry needs to be managed).

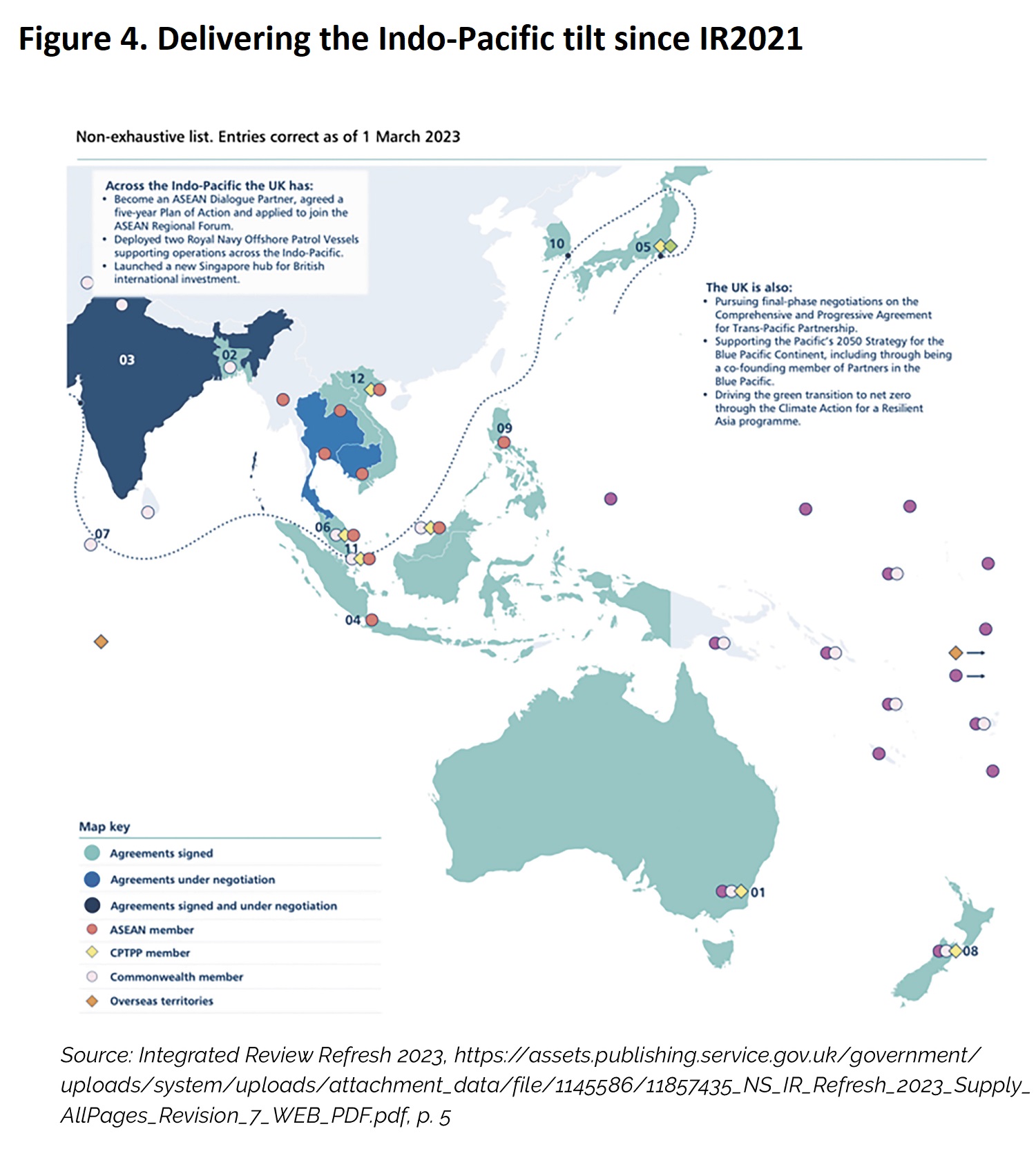

How a state views the world also informs how they conceptualise it publicly. This is demonstrated by the UK’s Integrated Review Refresh 2023. 66 Under the title ‘Delivering the Indo-Pacific tilt’, a map is provided of the UK’s Indo-Pacific activities. It centres around who it has partnered with in the mega-region, which appears to stretch to the Indian Ocean only to the extent of India (see Figure 4).

Of course, the meaningful inclusion of African states in the Indo-Pacific narrative is also up to African partners themselves. As of mid-2023, there existed no African state strategy or joint African Union (AU) vision towards the Indo-Pacific. Countries like Kenya have begun to articulate a position but this has largely been publicised through a series of statements. 67 While Africa’s position is represented by the AU-led Africa’s Integrated Maritime Strategy (AIMS) 2050, this document is outdated and does not account for current trends and changes. For now, African positions and interests are expressed in the IORA outlook, which has nine African member states. However, they compete with other member states and dialogue partners who have already articulated Indo-Pacific positions that inform their IORA engagement. The continent is therefore at risk of having geography and policy set out by others that are not informed of its own articulation and interests.

Challenges to the Indo-Pacific: China’s BRI in Africa

While the Indo-Pacific narrative is being promoted by strategies, its degree of resonance is still taking shape in Africa. In fact, there are other interpretations and narratives that overlay this geographic space. In particular, since 2013 China has been promoting its BRI narrative, a global regional-integration drive, and subsequently other initiatives. 68 While the BRI is not perfect, 69 China’s interpretation therein of the Indian and Pacific Ocean region seems to find more resonance as a narrative for African policy elites.

In order for narratives to have impact among audiences, 70 they need to be compelling, fit pre-existing ideas and narratives, and have the potential to change audiences’ minds. In the African context, China’s BRI has somewhat achieved this in relation to the Indo-Pacific:

- Compelling narrative: When the BRI was created, Africa’s role in it was a question mark. It has now become ‘an important direction for the joint construction of [the] BRI’ (part of this has to do with the relatively positive reception of the initiative by African policymakers). 71 China’s engagement through the BRI has also been qualitative, supported by a level of institutionalisation incorporating African partners in BRI summits and the signing of memorandums of understanding (MOUs) – such as South Africa (2015), Egypt (2016) and Kenya and Ethiopia (2017). China has also readily promoted itself as a reliable partner for Africa, as was demonstrated by its regular engagement and support of African partners during the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, 72 when other external partners withdrew.

- Pre-existing narratives: A successful aspect of the BRI is that it complements the African development agenda and narratives, such as the AU-driven development blueprint Agenda 2063. 73 China’s second Africa policy paper (2015) did not actually refer to the BRI. 74 Instead, it emphasised the boosting of African industrialisation – although in content they essentially share the same interest areas. There has also been a commitment to ‘ensure synergies between BRI and the African development agenda’, 75 and in this way the narrative of the BRI in Africa is coconstituted. The co-constitution of initiatives/narratives resonates with China’s approach to the Indo-Pacific, where it may not subscribe to the concept but has put its support behind others, 76 mirroring ASEAN and India’s positions towards the mega-region. This opens space for China to engage in the formulation of how the evolving Indo-Pacific is conceptualised.

Conclusion: Implications for the Indo-Pacific and BRI narratives

It appears that the Indo-Pacific narrative, promoted by certain state strategies, frames China as a challenge to be managed and also unevenly accounts for African states’ involvement. Meanwhile, from an African policy perspective, where there has yet to be conceptualisation towards the IndoPacific, there is engagement and, to an extent, alignment with China’s BRI narrative. However, there is also a degree of ownership in that African states themselves have not established official positions towards the Indo-Pacific from which others can engage. There are lessons to be learnt in the agency applied by ASEAN in relation to the Indo-Pacific and China: since 2019, its narrative of ASEAN ‘centrality’ has conceptualised the group of countries as the physical and imagined centre of the Indo-Pacific. In turn, both the strategies of 2021–2022 and China have largely supported this notion in their approaches.

Yet beyond the policy space, neither the BRI nor the US-led Indo-Pacific narratives are actually ‘winning’ in the eyes of African audiences. Surveys such as Afrobarometer’s 34-country survey on African perceptions towards China, 77 corroborated by a Randcorp study on perceptions in selected Indo-Pacific states, 78 find that the US and China are largely on a par in terms of perceived degree of influence. However, they are viewed as influential in different ways. For example, Afrobarometer’s results reflect that 59% of respondents see China as ‘somewhat positive’ and ‘very positive’ in terms of its perceived political and economic influence in their respective countries. Similarly, the US was at 58%. (Meanwhile Randcorp disaggregates the US influence in the Indo-Pacific to the diplomatic and military spaces and China to economic development.) Additionally, the Afrobarometer survey takes into account other influences, such as regional powers, regional alliances, Russia and even United Nations’ agencies. Although they all fall behind the US and China in terms of influence, they could eventually add alternative sources of narratives. The local environment and its reception of narratives therefore has an impact on the diffusion of foreign policy ideas.

In conclusion, in an information age where narratives can be readily communicated across regions and perpetuated through policies and media, there is also a counterflow where regions and societies can then interpret such narratives to a point where they are co-created, countered or even rejected.

About the authors

Folashadé Soulé is a Senior Research Associate at the Global Economic Governance programme (Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford). Her research areas focus on Africa–China relations, the study of agency in Africa’s international relations and the politics of South–South cooperation.

Lina Benabdallah is Associate Professor of Politics and International Affairs at Wake Forest University. She is the author of Shaping the Future of Power: Knowledge Production and Network-Building in China–Africa Relations (University of Michigan Press, 2020).

Cobus van Staden is the managing editor and co-founder of the China-Global South Project, a startup tracking China’s engagement with the developing world. He is a non-resident research fellow with the US Institute of Peace and with Stellenbosch University Department of Journalism.

Yunnan Chen is a Research Fellow at the ODI, London, in the Development and Public Finance programme. Her work centres around the changing development finance and export credit architecture, and the role of global China.

Yu-Shan Wu is a Research Fellow with the Ocean Regions Programme, Department of Political Sciences, University of Pretoria. She holds a PhD (International Relations) from the same university. She is currently interested in the future of global order, specifically perspectives from the global South.

Endnotes

Debt traps and other stories: The Western counter-narration of Africa–China relations

- United States Mission to the United Nations. 2022. Explanation of vote on a Third Committee Resolution on the Right to Development, 10 November, https://usun.usmission.gov/explanation-of-vote-on-a-third-committee-resolution-onthe-right-to-development/.

- CGTN. 2023. Shared human values: Chinese official calls for common ground, respecting every country’s path to democracy, 24 March, https://news.cgtn.com/news/2023-03-24/VHJhbnNjcmlwdDcxMTk3/index.html.

- National Development and Reform Commission of the People’s Republic of China. 2023. Chinese path to modernization: The way forward, China Daily, 26 April, https://en.ndrc.gov.cn/news/mediarusources/202304/ t20230428_1355489.html.

- Global Times. 2023. Chinese modernization not pursued by war, colonization or exploitation, busting the myth that modernization is Westernization: FM, 7 March, https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202303/1286795.shtml.

- Brahma Chellaney. 2017. China’s debt-trap diplomacy, Project Syndicate, 23 January, https://www.project-syndicate.org/ commentary/china-one-belt-one-road-loans-debt-by-brahma-chellaney-2017-01.

- Sam Parker and Gabrielle Chefitz. 2018. Debtbook diplomacy: China’s strategic leveraging of its newfound economic influence and the consequence for U.S. foreign policy. Harvard Kennedy School Belfer Center, 24 May, https://www. belfercenter.org/publication/debtbook-diplomacy.

- Maria Abi-Habib. 2018. How China got Sri Lanka to cough up a port, New York Times, 25 June, https://www.nytimes. com/2018/06/25/world/asia/china-sri-lanka-port.html.

- Global Times. 2020. China hits back at Pompeo’s ‘debt-trap’ diplomacy claim, 13 October, https://www.globaltimes.cn/ content/1203380.shtml.

- Deborah Brautigam. 2019. A critical look at Chinese ‘debt-trap diplomacy’: The rise of a meme. Area Development and Policy, 5(3): 1–14, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/23792949.2019.1689828; see also: Umesh Moramudali. 2020. The Hambantota Port deal: Myths and realities, The Diplomat, 1 January, https://thediplomat.com/2020/01/thehambantota-port-deal-myths-and-realities/.

- Eric Martin and Justin Sink. 2023. Biden jabs at China ‘debt-trap diplomacy’ at Americas summit, Bloomberg, 3 November, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-11-03/biden-jabs-at-china-s-debt-trap-diplomacy-atamericas-summit.

- Olivia Solon. 2013. Richard Dawkins on the internet’s hijacking of the word ‘meme’, Wired, 20 June, https://www. wired.co.uk/article/richard-dawkins-memes.

- Globely News. 2022. Uganda airport deal: A Chinese belt and road debt trap? 7 March, https://globelynews.com/africa/ china-takes-international-airport-of-uganda/.

- Comedy Central. 2021. If you don’t know, now you know: China’s Africa investments, 16 December, https://www. cc.com/video/xhwr8p/the-daily-show-with-trevor-noah-if-you-don-t-know-now-you-know-china-s-africa-investments.

- Bloomberg TV. 2023. U.S. Ambassador to UN Thomas-Greenfield on Somalia, Russia, China, https://www.youtube. com/watch?v=43IEt3J72OI.

- Eric Olander. 2023. The China debt story in Nigeria makes headlines even when it shouldn’t. The China-Global South Project, 8 March, https://chinaglobalsouth.com/2023/03/08/the-china-debt-story-in-nigeria-makes-headlines-evenwhen-it-shouldnt/.

- Nigerian Debt Management Office. Nigeria’s external debt stock as of September 30, 2023. Debt Management Office Nigeria, https://www.dmo.gov.ng/debt-profile/external-debts/external-debt-stock/4496-nigeria-s-external-debt-stock-asat-september-30-2023/file.

- International Monetary Fund. 2023. Africa: Special issue, October 2023. IMF eLibrary, 10 October, https://www. elibrary.imf.org/display/book/9798400254772/9798400254772.xml.

- Nicolas Lippolis and Harry Verhoeven. 2022. Politics by default: China and the global governance of African debt. Global Politics and Strategy, 64(3), https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2022.2078054.

Borrowing for belts and roads: The double edge of China’s infrastructure lending in Africa

- Deborah Brautigam. 2019. A critical look at Chinese ‘debt-trap diplomacy’: The rise of a meme. Area Development and Policy, 5(1): 1–14, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/23792949.2019.1689828.

- Rolland Nadege. 2017. China’s Eurasian century? Political and strategic implications of the Belt and Road Initiative. The National Bureau of Asian Research, 23 May.

- Jia Wenshan. 2018. Western critics are wrong: China’s belt and road is good for the world, South China Morning Post, March, https://www.scmp.com/comment/insight-opinion/article/2136325/chias-belt-and-road-initiative-good-world-despite-what.

- Chen Yunnan. 2021. Laying the tracks: The political economy of railway development in Ethiopia’s railway sector and implications for technology transfer. Boston University Global Development Policy Center, GCI Working Paper 014, 25.

- Philipp Rode, Terrefe Biruk and Nuno F. da Cruz. 2020. Cities and the governance of transport interfaces: Ethiopia’s new rail systems. Transport Policy, 91: 76–94, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2020.03.004.

- Yuan Wang and Uwe Wissenbach. 2019. Clientelism at work? A case study of Kenyan Standard Gauge Railway project. Economic History of Developing Regions: Africa and China: Emerging Patterns of Engagement, 34(3): 280–299.

- Ian Taylor. 2020. Kenya’s new lunatic express: The Standard Gauge Railway. African Studies Quarterly, 19(3–4): 24.

- GCR. 2018. Kenyan workers’ strike halts Chinese railway project—News—GCR, Global Construction Review, 5 January, http://www.globalconstructionreview.com/news/kenyan-workers-strike-halts-chinese-railway-projec/; David Pilling. 2019. It is wrong to demonise Chinese labour practices in Africa, Financial Times, 3 July, https://www.ft.com/content/6326dc9a-9cb8-11e9-9c06-a4640c9feebb.

- CNN and Jenni Marsh. 2018. UN bribery case exposes Chinese corruption in Africa, CNN, 9 February, https://www.cnn.com/2018/02/09/world/patrick-ho-corruption-china-africa/index.html; AS Isaksson and Andreas Kotsadam. 2018. Chinese aid and local corruption. Journal of Public Economics, 159: 146–159, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2018.01.002; Yuan Wang and Uwe Wissenbach. 2019. Clientelism at work? A case study of Kenyan Standard Gauge Railway project. Economic History of Developing Regions, 34(3): 280–299, https://doi.org/10.1080/20780389.2019.1678026.

- Deborah Brautigam and Won Kidane. 2020. China, Africa, and debt distress: Fact and fiction about asset seizures. China Africa Research Initiative, Policy Brief 47, p. 4; Brahma Chellaney. 2017. China’s debt-trap diplomacy, Project Syndicate, 23 January, https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/china-one-belt-one-road-loans-debt-by-brahmachellaney-2017-01; Ajit Singh. 2020. The myth of ‘debt-trap diplomacy’ and realities of Chinese development finance. Third World Quarterly, 42(2): 239–253, https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2020.1807318.

- Kai Schultz. 2017. Sri Lanka, struggling with debt, hands a major port to China, New York Times, 13 December, https:// www.nytimes.com/2017/12/12/world/asia/sri-lanka-china-port.html.

- Yasiin Mugerwa. 2021. Uganda surrenders key assets for China cash, Monitor, 5 December, https://www.monitor.co.ug/uganda/news/national/uganda-surrenders-airport-for-china-cash-3631310.

- Agatha Kratz, Allen Feng and Logan Wright. 2019. New data on the 'debt trap' question. Rhodium Group, 29 April, https://rhg.com/research/new-data-on-the-debt-trap-question/; Deborah Brautigam and Won Kidane. 2020. China, Africa, and debt distress: Fact and fiction about asset seizures. China Africa Research Initiative, Policy Brief 47, p. 4.

- PRC Embassy Zambia, Remarks by Spokesperson of the Chinese Embassy on U.S. Official’s Statement about Zambia’s Debt Issue Related to China. Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the Republic of Zambia, January 2023, http://zm.chinaembassy.gov.cn/eng/hdytz/202301/t20230124_11014281.htm.

- Nyabiage, Jevans. “China Is behind Billion Dollar Debt Restructure for Angola, Analysts Say | South China Morning Post.” Accessed March 23, 2023. https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3102530/china-behind-billiondollar-debt-restructure-angola-analysts.

- Yunnan Chen. 2021. Laying the tracks: The political economy of railway development in Ethiopia’s railway sector and implications for technology transfer. Boston University Global Development Policy Center, GCI Working Paper 014, p. 25.

- Hangwei Li and Jacqueline Muna Musiitwa. 2020. China in Africa’s looking glass: Perceptions and realities, RUSI, August, https://rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/commentary/china-africas-looking-glass-perceptionsand-realities.

- Edem Selormey and Josephine Appiah-Nyamekye Sanny. 2021. Africans welcome China’s influence but maintain democratic aspirations. Afrobarometer, Dispatch No. 489, 15 November, https://www.afrobarometer.org/wp-content/ uploads/2022/02/ad489-pap3-africans_welcome_chinas_influence_maintain_democratic_aspirations-afrobarometer_ dispatch-15nov21.pdf.

- Kate Bartlett. 2022. Survey: Africans see China as positive force, Voice of America, October, https://www.voanews. com/a/survey-africans-see-china-as-positive-force/6813313.html.

- Felix Kipkemoi. 2022. Why Kenya got a raw deal in SGR agreement with China, The Star, November, https://www.thestar.co.ke/news/2022-11-07-why-kenya-got-a-raw-deal-in-sgr-agreement-with-china/; Okoa Mombasa. 2023. Ex-government auditor alleges massive irregularities and fraud in SGR funding, July, https://www.okoamombasa.org/en/ news/massive-irregularities-fraud-sgr-funding/; Yun Sun. 2020. COVID-19, Africans’ hardships in China, and the future of Africa-China relations, Brookings, April, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/covid-19-africans-hardships-inchina-and-the-future-of-africa-china-relations/.

- A Gelpern, S Horn, S Morris, B Parks and C Trebesch. 2021. How China lends: A rare look into 100 debt contracts with foreign governments. AidData, Kiel Institute, CGDev, PIIE: 85; K Lui and Y Chen. 2021. The evolution of China’s lending practices on the Belt and Road: Emerging analysis. ODI, 25.

- Poorva Karkare, Linda Calabrese, Sven Grimm and Alfonso Medinilla. 2020. European fear of ‘missing out’ and narratives on China in Africa. ETTG, July, file:///Users/apriintern/Downloads/ETTG-European-fear-of-missing-outand-narratives-on-China-in-Africa.pdf.

- D Meredith and Y Chen. 2023. Five takeaways from the Global Gateway Forum. ODI: Think Change, November, https://odi.org/en/insights/five-takeaways-from-the-global-gateway-forum/.

- Ibid.

- Yunnan Chen and Zoe Liu Zongyuan. 2023. Hedging belts, de-risking roads: Sinosure in China’s overseas finance and the global challenge and response. ODI Report, https://odi.org/en/publications/hedging-belts-de-risking-roads-sinosurein-chinas-overseas-finance-and-the-evolving-international-response/.

What the Indo-Pacific narrative tells us about China and Africa

- Yunnan Chen, Raphaëlle Faure and Nilima Gulrajani. 2023. Crafting development power: Evolving European approaches for a world in polycrisis (Donors in a post-aid world). ODI Report, https://odi.org/en/publications/ crafting-development-power-evolving-european-approaches-in-an-age-of-polycrisis/.

- Ulrich Ecker, Michael Jetter and Stephan Lewandowsky. 2020. How Trump uses Twitter to distract the media – new research, The Conversation, November, https://theconversation.com/how-trump-uses-twitter-to-distract-the-medianew-research-149847.

- Yu-Shan Wu. 2019. Reporting on China in Africa is too binary. What needs to be done to fix it, The Conversation, 28 April, https://theconversation.com/reporting-on-china-in-africa-is-too-binary-what-needs-to-be-don-to-fixit-115644.

- Arturo Sant-Cruz. 2022. From Asia-Pacific to the Indo-Pacific, in three different world(view)s. Redalyc Journal, January, https://www.redalyc.org/journal/4337/433771271002/html/.

- Australian Government, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. 2023. The Quad, https://www.dfat.gov.au/ international-relations/regional-architecture/quad.

- The future of the Indo-Pacific – Japan’s new plan for a ‘free and open Indo-Pacific’ – ‘Together with India, as an indispensable partner’, 2022, https://www.mofa.go.jp/files/100477790.pdf.

- HM Government, UK. 2023. Integrated Review Refresh 2023: Responding to a more contested and volatile world, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_datafile/1145586/11857435_NS_IR_Refresh_2023_Supply_AllPages_Revision_7_WEB_PDF.pf.

- ASEAN. 2019. ASEAN outlook on the Indo-Pacific, https://asean.org/asean2020/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/ASEAN-Outlook-on-the-Indo-Pa c_FINAL_22062019.pdf.

- Cyril Ip. 2022. Xi Jinping says China will ‘consider’ hosting Belt and Road Forum in 2023, SCMP, 18 November, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3200182/xi-jinping-says-china-will-cosider-hosting-belt-androad-forum2023?campaign=3200182&module=perpetual_scroll_0&pgtype=article.

- Yu-Shan Wu. 2022. Beyond ‘Indo-Pacific’ as a buzzword: Learning from China’s BRI experience. South African Journal of International Affairs, 29(1), https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10220461.2022.2042373.

- Kyodo. 2023. Foreign Minister Hayashi to join EU meeting on Indo-Pacific in Sweden, Japan Times, 29 May, https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2023/05/09/national/hayashi-eu-meeting-indo-pacific-focus/.

- Thomas Manch. 2022. Explainer: Why you keep hearing about the ‘Indo-Pacific’, Stuff, July, https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/explained/128730027/explainer-why-you-keep-hearing-abou-the-indopacific.

- Australian Government, Department of Prime Minister and Government. 2023. Quad leaders’ summit 2023, https:// www.pmc.gov.au/resources/quad-leaders-summit-2023.

- Roundtable discussion on the ‘Geopolitics of the Indo-Pacific’ held at the Institute for Security Studies (ISS), Pretoria, South Africa, 10 November 2022.

- M Schoeman and Yu-Shan Wu. 2022. The evolving Indo-Pacific region: An introduction to external perspectives on Africa’s role and position. Strategic Review for South Africa, 44(2), https://upjournals.up.ac.za/index.php/strategic_ review/article/view/4417/3869.

- Rory Medcalf. 2019. Indo-Pacific visions: Giving solidarity a chance. The National Bureau of Asian Research, Seattle, Washington, July, https://www.nbr.org/wp-content/uploads/pdfs/publications/ap14-3-medcalf-july2019.pdf.

- HM Government, UK. 2023. Integrated Review Refresh 2023: Responding to a more contested and volatile world, March, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_datafile/1145586/11857435_NS_IR_Refresh_2023_Supply_AllPages_Revision_7_WEB_PDF.pf.

- Sankalp Gurjar. 2021. How Kenya views the Indo-Pacific. Indian Council of World Affairs, 1 October, https://www.icwa.in/show_content.php?lang=1&level=3&ls_id=6424&lid=4415.

- Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the Republic of Seychelles. 2022. Global Development Initiative and Global Security Initiative – China’s latest solutions to world peace, security and development. Chinese Embassy in Seychelles, 5 August, https://docs.google.com/document/d/14fu1VSeMFhapoMGtRd4n-NiXnPSKB31t1y2RlZ4FM78/edit.

- Lokanathan Venkateswaran. 2023. China’s Belt and Road Initiative: Implications in Africa, ORF, 10 May, https://www.orfonline.org/research/chinas-belt-and-road-initiative-implications-in-africa.

- Laura Roselle, Alister Miskimmon and Ben O’Loughlin. 2014. Strategic narrative: A new means to understand soft power. Sage Journals, 7(1), https://doi.org/10.1177/17506352135166.

- Yu-Shan Wu. 2022. Beyond ‘Indo-Pacific’ as a buzzword: Learning from China’s BRI experience. South African Journal of International Affairs, 29(1), https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10220461.2022.2042373.

- Cobus van Staden and Yu-Shan Wu. 2021. Vaccine diplomacy and beyond: New trends in Chinese image-building in Africa. SAIIA Occasional Paper, June, https://saiia.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Occasional-Paper-327-vanstaden-wu.pdf.

- African Union. 2013. Agenda 2063: The Africa we want, https://au.int/en/agenda2063/overview.