This article is part of the BRICS thought leadership series, published by APRI in collaboration with the University of Johannesburg. It explores key themes from the 16th BRICS Summit and the group's broader initiatives. The series is edited by Ada Mare, Bhaso Ndzendze, Serwah Prempeh.

Background

Since 2009, Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa (BRICS) have issued an intergovernmental declaration every year. The Head of State reads each annual declaration from the hosting country, which alternates among the five countries. Although the host country’s Head of State delivers the declaration verbally on the last day of the BRICS leaders’ gathering, it remains an intergovernmental statement expressing the shared position of the five BRICS countries. It is a documented statement based on the previous ministerial and other government-approved exchanges among the five countries.

Under Russian chairmanship, the theme for this year’s BRICS summit was entitled ‘Strengthening Multilateralism for Equitable Global Development and Security’. The first intergovernmental summit in 2009 was primarily concerned with the emerging countries’ resilience to the global financial crisis, which led to them being regarded as challengers of the status quo in the world economic order. Fifteen years later, the group’s focus has transformed from the five countries’ concerns about advanced economies’ vulnerability to financial crises to becoming collectively involved in finding solutions for global development problems and creating new areas for cooperation among themselves and countries from the majority world. Meanwhile, global geopolitical events, including Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and escalating tensions in the Southwest Asian and North African (SWANA) region, have spiralled into crises.

Given the evolution of BRICS from a financial buzzword in 2001 to an intergovernmental configuration in 2009, this article aims to explore the essence of the first ten annual declarations. It argues that, due to their response to the global financial crisis, there were noticeable successes in transforming the members’ declared statements into implemented actions during their initial years. Based on content analysis, three questions are asked. First, whose interests does the BRICS configuration represent? Second, what are the common themes in their declarations? Third, is there a gap between their declared statements and practical outcomes?

The insights gained from this study contribute to ongoing conversations about the purpose and global impact of BRICS. The study concludes that despite differences in their respective country dynamics and governmental responses to global crises, the five countries manage to collectively construct the idea that their extended alliance is intended to enhance world order. However, beyond their declarative statements, there is an ongoing lack of clarity about BRICS policy coordination and implementation, which suggests that consistent annual gatherings alone are insufficient measures of their success. Implementing declared statements matters to substantiate the BRICS notion of acting in the majority world’s interests.

Background on the intergovernmental declarations

The annual BRICS leaders’ declaration contains a set of documented commitments proclaiming the intentions and shared vision of the five countries’ governments for the world order and their potential for collective coordination to address matters related to global development, economic growth and international affairs. Although the declarations are non-binding documents, they are noteworthy because they communicate shared perceptions from the five different governments on various topics. They receive considerable media attention and coverage in foreign policy analyses when issued. The documents are not meant to impose legal obligations on any of the governments. Instead, the declarations echo their harmonised vision, their perceptions of matters of mutual concern in the world order, their planned course of action to address global challenges and their commitments towards one another.

Over time, the BRICS configuration has transformed into an unlikely intergovernmental convergence. Even though they share few economic and political commonalities – since they follow diverging domestic governance models and operate their respective economies according to contrasting ideologies – since 2009 the five countries have managed to sustain their grouping as an intergovernmental politico-economic arrangement. This setup has been artificially established since it did not materialise intrinsically as a result of traditional intergovernmental initiatives. Instead, Jim O’Neill coined the acronym ‘BRIC’ in 2001 in a Goldman Sachs’s report comparing the real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth of the initial four countries with the advanced G7 economies. He predicted that the emerging BRIC markets would outperform some of the G7 in the long run. Building on this report’s narrative, especially in the aftermath of the 2007-8 financial crisis, which affected developed economies more than emerging countries, the four BRIC countries started to reflect on the prospect of their collective coordination to address world problems.

While the millennium’s first two decades have seen a surge in the number of country acronyms of a semi-peripheral character, none has matched the degree of intergovernmental formalisation achieved by BRICS. For example, VISTA, E7, N11, CIVETS, MINT, BRIICS and TIMBI are other abbreviated country groupings from the non-core sphere of the international system. The BRICS configuration is the most remarkable regarding real-world output among these groupings. Over the years, the once neutrally coined acronym in a Western investment bank’s report transformed into an intergovernmental organisation capable of articulating coordination over important areas in global politics. The five states have not surrendered any power through their interactions. Instead, there is an attempt at harmonisation regarding what they consider to be pressing global development issues.

BRICS declarations’ overall essence: Whose interests do they represent?

Based on a systematic content analysis of the first ten declarations, Table 1 describes how BRICS intergovernmental declarations fluctuate in length. The content analysis indicates that the range of items they cover is broad. Nevertheless, there is one common pattern. Although the annual statements may be structured differently, every declaration emphasises the idea that the BRICS configuration speaks on behalf of low-income, emerging and developing countries.

Table 1: Overview of BRICS’ first ten declarations

| Year | Host Country | Declaration Statement | Number of Statement Points | Extract from Declaration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | Russia | Joint Statement of the BRIC Countries' Leaders | 16 | ‘We are committed to advance the reform of international financial institutions, so as to reflect changes in the global economy. The emerging and developing economies must have greater voice and representation in international financial institutions’ (note 3). |

| 2010 | Brazil | Second BRIC Summit of Heads of State and Government: Joint Statement | 31 | ‘We stress the central role played by the G-20 in combating the crisis through unprecedented levels of coordinated action…’ (note 3). |

| 2011 | China | Third BRICS Summit: Sanya Declaration Broad Vision, Shared Prosperity |

32 | ‘We affirm that the BRICS and other emerging countries have played an important role in contributing to world peace, security and stability…’ (note 5). |

| 2012 | India | Fourth BRICS Summit: Delhi Declaration BRICS Partnership for Global Stability, Security and Prosperity |

50 | ‘We stand ready to work with others, developed and developing countries together, on the basis of universally recognized norms of international law and multilateral decision making, to deal with the challenges and the opportunities before the world today. Strengthened representation of emerging and developing countries in the institutions of global governance will enhance their effectiveness in achieving this objective’ (note 4). |

| 2013 | South Africa | Fifth BRICS Summit BRICS and Africa: Partnership for Development, Integration and Industrialisation |

47 | ‘We are open to increasing our engagement and cooperation with non-BRICS countries, in particular Emerging Market and Developing Countries (EMDCs), and relevant international and regional organisations’ (note 3). |

| 2014 | Brazil | 6th BRICS Summit: Fortaleza Declaration Inclusive Growth: Sustainable Solutions |

72 | ‘We renew our openness to increasing engagement with other countries, particularly developing countries and emerging market economies, as well as with international and regional organisations, with a view to fostering cooperation and solidarity in our relations with all nations and peoples’ (note 3). |

| 2015 | Russia | VII BRICS Summit: Ufa Declaration BRICS Partnership – a Powerful Factor of Global Development |

77 | ‘The global recovery continues, although growth remains fragile, with considerable divergences across countries and regions. In this context, emerging markets and developing countries (EMDCs) continue to be major drivers of global growth’ (note 11). |

| 2016 | India | 8th BRICS Summit Building Responsive, Inclusive and Collective Solutions |

110 | ‘We agree that BRICS countries represent an influential voice on the global stage through our tangible cooperation, which delivers direct benefits to our people. [We will work] to ensure that the increased voice of the dynamic emerging and developing economies reflects their relative contributions to the world economy, while protecting the voices of least developed countries, poor countries and regions’ (note 3). |

| 2017 | China | 9th BRICS Summit: BRICS Leaders Declaration BRICS: Stronger Partnership for a Brighter Future |

71 | ‘Our cooperation since 2006 has fostered the BRICS spirit featuring mutual respect and understanding, equality, solidarity, openness, inclusiveness and mutually beneficial cooperation, which is our valuable asset and an inexhaustible source of strength for BRICS cooperation… We have furthered our cooperation with emerging markets and developing countries (EMDCs). We have worked together for mutually beneficial outcomes and common development, constantly deepening BRICS practical cooperation which benefits the world at large’ (note 3). |

| 2018 | South Africa | 10th BRICS Summit: Johannesburg Declaration BRICS in Africa: Collaboration for Inclusive Growth and Shared Prosperity in the 4th Industrial Revolution |

102 | ‘We reaffirm our commitment to the principles of mutual respect, sovereign equality, democracy, inclusiveness and strengthened collaboration’ (note 5). |

On account of the content analysis and trends observed in the declarations, it is observed that the BRICS leaders and their government-sanctioned platforms are actively involved in discursive practices which confirm that the BRICS configuration shares a common vision in the interests of the majority world: they intend to redress the inequalities caused by the ways of functioning of developed economies. The BRICS initial intergovernmental declarations present their own agenda from a positive angle and as a better model for the majority world (Kodabux, 2023). They are deploying strategies to appeal to stakeholders from BRICS and convince developing countries that the five governments are working collectively in their interests on the global stage.

BRICS common themes

Common themes observable in BRICS’ statements can be grouped under five categories: ‘practical cooperation’, ‘global economic governance’, ‘international security’, ‘cultural diversity’ and ‘principles’. These capture the configuration’s ideas: ‘[First,] [p]ractical cooperation among BRICS countries and partnership with other countries in diverse sectors has the potential to reach concrete outcomes in international society’s interests. [Second,] [t]he existing global financial architecture lacks transparency and is discriminatory for emerging and developing countries. The global economic governance structures need to be reformed to reflect inclusiveness and representativeness in the world order. [Third,] [g]lobal threats and challenges exist in different forms and jeopardise international security. Poor and developing communities are particularly susceptible. Existing institutions should be reformed to address conflicts and threats and reach consensus-based decisions multilaterally. [Fourth,] cultural diversity is the foundation of BRICS cooperation. Sustainability of common vision and intra-BRICS projects [are] achieved through exchanges and cooperation in various civil society areas (media, think tanks, youth, parliament forums, local governments, trade union forums, etc.). [Fifth,] [a]ll of the previous themes are based on shared “principles of openness, solidarity and mutual assistance” amongst other ideals and values cherished by the BRICS countries’ (Kodabux, 2023).

A preliminary conclusion derived from the intergovernmental declarations is that although the five states operate differently, they can articulate their vision for global economic governance, multilateralism in international affairs, or fairer trade practices using principles that appeal to developing countries. Based on an analysis of BRICS documents, these principles include: ‘greater voice’, ‘fair burden-sharing’, ‘shared perception’, ‘coherence’, ‘pragmatism’, ‘legitimacy’, ‘resistance to unilateralism’, ‘common but differentiated responsibility’, ‘openness’ and ‘rules-based order’. Expressed in relation to redressing North-South development imbalances, the principles are not rhetorical statements: They suggest the BRICS countries operate differently from developed economies. Indeed, they have, in their early years, demonstrated that they act in the interests of the majority world, as evidenced in the next section.

Declarations vs implementation: What do we know about it?

The content analysis of the declarations indicates that the cooperation areas among BRICS countries were created first on a discursive level. Some of their declarations about working for the majority of the world’s interests have manifested in practical responses to the 2007-8 global financial crisis. For example, the BRICS governments used the argument about how their economies fared better than the G7 economies during the crisis to set the agenda for the G20 summit in 2009 (The Economist, 2009). The G20 has served as the BRICS’ ‘premier forum for [their] international economic cooperation’ (G20 Information Centre, 2009). BRICS also directed discussions of the 2010 G20 summit according to their agenda.

Between 2008 and 2010, the intergovernmental group of emerging economies was successful in convening discussions about the topics of openness, meritocracy, rules-based order and fairness. Although the G20 is an informal bloc whose summit declarations are non-binding, akin to the other blocs such as the G7 or G8, it is an important space for major industrialised and developing economies to discuss matters pertaining to international financial stability. The G20 summit is an expansion of ‘the centre of global governance to include ascending powers alongside advanced ones, and to give each equal, institutionalised involvement and influence in the central club’ (Kirton, 2010 p. 2). Due to this summit’s representation as the centre for global economic governance and the space it offers to discuss matters about the health of the world economy, the BRICS leaders have stressed the central role played by the G20,as opposed to the G7 or G8, in dealing with financial issues (BRICS Information Centre, 2009 notes 1–2; 2010 note 3; 2011 notes 14–15; 2012 note 7). In their initial BRICS declarations (2009 note 3; 2010 notes 10–11; 2011 notes 15–16; 2012 9–10), the leaders recommended actions which have been addressed and implemented at the G20 summit, namely in the International Monetary Fund (IMF) quota reforms, whereby the members committed to transfer a share of the quotas to underrepresented countries.

Additionally, the four initial BRIC leaders also requested urgent reforms in the World Bank. They demanded ‘a substantial shift in voting power in favour of emerging market economies and developing countries’ (BRICS Information Centre, 2009). Faced with this pressure, the World Bank initiated its ‘first general capital increase’ in over twenty years, which resulted in a ‘shift in voting power to developing countries’ (World Bank, 2010). Requesting stronger and more flexible aid from multilateral development banks has been another area where the political class of the configuration advocated for support of developing economies. In their 2010 intergovernmental declaration, they stated: ‘We support the increase of capital, under the principle of fair burden-sharing, of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development and of the International Finance Corporation, in addition to more robust, flexible and agile client-driven support for developing economies from multilateral development banks’ (BRICS Information Centre, 2010). The outcome was that during the 2010 G20 summit, the members, along with a significant contribution from BRIC countries, committed to increase the resources available to the IMF ‘by USD 6 billion through the proceeds from the agreed sale of IMF gold … [which expanded] the IMF’s concessional financing for the poorest countries’ (International Monetary Fund, 2010). BRICS governments also promoted the implementation of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and ensured that the poorest countries’ efforts are not hindered due to the aftereffects of the financial crisis. As a result, they called for policy recommendations, ‘technical cooperation, and financial support to poor countries in implementation of development policies and social protection for their populations’ (BRICS Information Centre, 2010 note 15). The G20 members responded to this call by committing ‘to put jobs at the heart of the recovery, to provide social protection, decent work and also to ensure accelerated growth in low income countries’ (G20 Seoul Summit Declaration, 2010 p. 1).

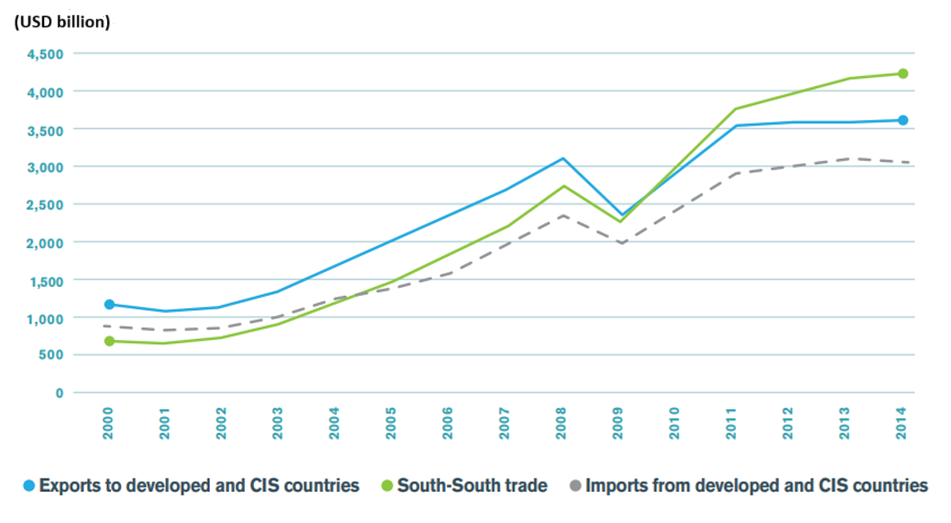

More recently, the BRICS countries have succeeded in demonstrating their intent to expand their cooperation beyond their five members. Since 2023, Iran, the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Egypt and Ethiopia have also become members of the BRICS alliance. The idea for a ‘BRICS Plus cooperation’ was formulated in their 2017 intergovernmental statement. While there are concerns about this expansion on account of its implications for Western hegemony, it is also relevant to underline that the BRICS Plus alliance is to date an informal arrangement. Non-BRICS countries and other regional organisations interact with BRICS countries according to individual interstate arrangements rather than through a formalised channel ‘with the group as a whole’ (European Parliament 2024). In fact, a related gap is observed when exploring the connection between the declared statements and the implemented actions. According to Pioch (2016), little is known about ‘BRICS [collective] policy coordination and cooperation’. For example, even if south-south trade intensified among developing countries in the first fifteen years of the millennium, as shown in Figure 1, it is inconclusive whether this was the result of BRICS initiatives or pre-existing agreements. When researching BRICS Trade Ministers’ documents, there is no revelation of common strategies which they might have developed as a result of their meetings (BRICS Trade Ministers, 2011–17). Instead, these documents expound on a conception of practical economic cooperation for open, fairer international trade in the interests of emerging and developing economies.

Figure 1: Developing economies’ merchandise trade with developing, developed and commonwealth independent states

Note. The data show how South-South trade plummeted between 2008 and 2009 but escalated after 2009.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the BRICS intergovernmental declarations contain multiple messages and ideas about the purpose and vision of the configuration for the majority world. There is an observable pattern in their discussion of issues that they frame as matters of mutual concern for present and future world politics. Despite the stark differences in their individual domestic settings, the five countries continue to be able to convene during their yearly summit and to issue their annual intergovernmental declaration. They have added new items to consider and have, over the years, welcomed the idea of adding new members to the configuration. In addition, contemporary geopolitical events continue to test their alliance. However, our findings show that declared statements do not match the practical outcomes of the BRICS countries’ collective initiatives. In other words, there is a need to address the gap between declaration and implementation to substantiate the claim that the BRICS countries act in the interests of the majority world.

The BRICS annual intergovernmental declarations merit further analysis beyond the first ten years of this article's scope. Annual gatherings at interstate or ministerial levels are insufficient measures of the configuration’s successes. Beyond their declarative statements, additional in-depth studies are required to explore the extent of BRICS collective policy coordination.

References

BRICS Information Centre. (2009). Joint statement of the BRIC countries’ leaders. http://www.brics.utoronto.ca/docs/090616-leaders.html

BRICS Information Centre. (2010). 2nd BRIC summit of heads of state and government: Joint statement. http://www.brics.utoronto.ca/docs/100415-leaders.html

BRICS Information Centre. (2011). Sanya declaration. http://www.brics.utoronto.ca/docs/110414-leaders.html

BRICS Information Centre. (2012). Fourth BRICS summit: Delhi declaration. http://www.brics.utoronto.ca/docs/120329-delhi-declaration.html

BRICS Information Centre. (2013). BRICS and Africa: partnership for development, integration and industrialisation: eThekwini declaration. http://www.brics.utoronto.ca/docs/130327-statement.html

BRICS Information Centre. (2014). The 6th BRICS summit: Fortaleza declaration. http://www.brics.utoronto.ca/docs/140715-leaders.html

BRICS Information Centre. (2015). VII BRICS summit: 2015 Ufa declaration. http://www.brics.utoronto.ca/docs/150709-ufa-declaration_en.html

BRICS Information Centre. (2016). 8th BRICS summit: Goa declaration. http://www.brics.utoronto.ca/docs/161016-goa.html

BRICS Information Centre. (2017). BRICS leaders Xiamen declaration. http://www.brics.utoronto.ca/docs/170904-xiamen.html

BRICS Information Centre. (2018). 10th BRICS summit Johannesburg declaration. http://www.brics.utoronto.ca/docs/180726-johannesburg.html

G20 Information Centre. (2009). The G20 Pittsburgh summit commitments. https://g20.utoronto.ca/analysis/commitments-09-pittsburgh.html

G20 Seoul Summit. (2010). The G20 Seoul summit leaders’ declaration November 11-12, 2010. https://g20.utoronto.ca/2010/g20seoul.pdf

International Monetary Fund. (2010). IMF resources and the G-20 summit. https://www.imf.org/external/np/exr/faq/sdrfaqs.htm

Kirton, J. (December 2010). The G20, the G8, the G5 and the role of ascending powers. https://g20.utoronto.ca/biblio/kirton-g20-g8-g5.pdf

Kodabux, A. (2023). BRICS countries’ annual intergovernmental declaration: why does it matter for world politics? Contemporary Politics, 29(4), 403-423.

The Economist. (2009). Not just straw men. https://www.economist.com/international/2009/06/18/not-just-straw-men

World Bank. (2010). World bank reforms voting power, gets $86 billion boost. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2010/04/25/world-bank-reforms-voting-power-gets-86-billion-boost

About the author

Adeelah Kodabux

Dr. Adeelah Kodabux is Director of LEDA, a research and advocacy organisation based in Mauritius, which focuses on enhancing data analyses related to African governance. She co-founded the Centre for African Smart Public Value Governance (C4SP). She graduated from Middlesex University London in 2020 with a PhD in International Relations. Her doctoral thesis is entitled ‘BRICS conversion of common sense into good sense: the relevance of a neo-Gramscian study for inclusive International Relations’.