This article is part of a series on the effects of the war in Ukraine on African countries. The series is edited by Chris O. Ogunmodede.

Summary

- Russia and Ukraine are major suppliers of fertilizers and African countries import a significant portion of their fertilizers. The ongoing war in Ukraine has caused a significant disruption in global supply chains, particularly for energy, food and fertilizers.

- Fertilizer prices have shot up significantly this year, compared to 2021. The spike in fertilizer prices is a major concern because of the effect it has on food prices across Africa.

- Under normal circumstances, one could hope that lower domestic production of food crops can be offset with increased imports. Unfortunately, the current crisis is a shock on a global scale which means that food prices have been on a steady rise this year.

- While most of the policy responses from within the continent have been focused on short-term schemes like input subsidies, this brief highlights the importance of long-term policy solutions, including investing in fertilizer manufacturing capacity, that African countries must adopt in order to boost their industrial capacity for fertilizer production.

I. Introduction

The ongoing war in Ukraine has caused a significant disruption in global supply chains, particularly for energy, food and fertilizers. The effect of the conflict on global fertilizer prices has been especially pronounced in Africa. This brief looks at the immediate effects of the Ukraine war on local fertilizer prices, as well as its likely impact on food production. While most of the policy responses from within the continent have been focused on short-term schemes like input subsidies, this brief highlights the importance of long-term policy solutions, including investing in fertilizer manufacturing capacity, that African countries must adopt in order to boost their industrial capacity for fertilizer production.

II. Fertilizer Trends

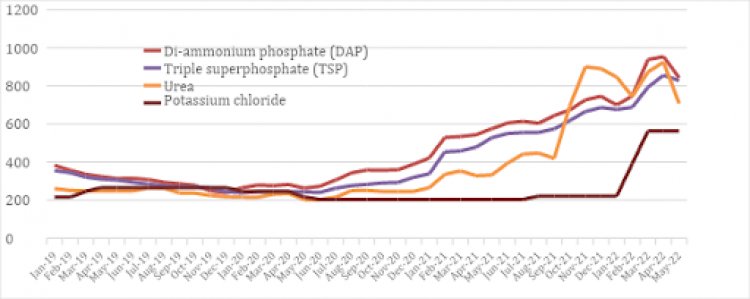

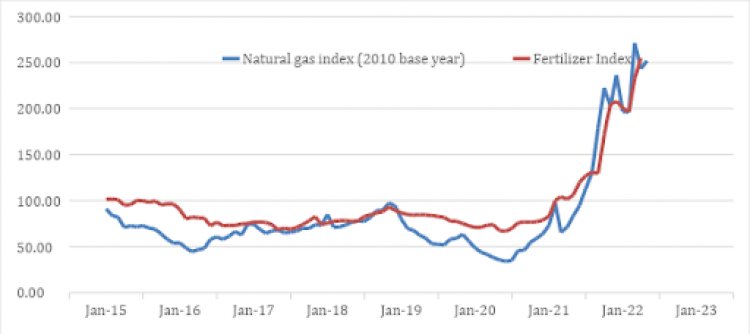

Fertilizer prices have shot up significantly this year, compared to 2021. By the second quarter of 2022, the prices of major fertilizers including di-ammonium phosphate, triple superphosphate, urea and potassium chloride more than doubled from the previous year (Figure 1). That price increase is not restricted solely to these major types of fertilizers. Indeed, the fertilizer price index shows a marked increase in growth (Figure 2), with a more than 100 percent increase from the first quarter of 2021 to the first quarter of 2022.

Figure 1: The changes in major fertilizer prices between January 2019 and May 2022

Across retail markets on the continent, the increase in the price of fertilizer has been even more drastic. In The Gambia and Senegal, the retail price of NPK fertilizer more than doubled between the first quarter of 2021 and the first quarter of 2022 while that of urea tripled over the same period. In Tanzania, the price increase is almost identical. Fertilizer prices in both The Gambia and Senegal are still twice as high as the preceding year, despite government subsidies. Even before the outbreak of war in Ukraine, fertilizer prices across Africa were higher in comparison to other regions of the world. In South Africa, for instance, the prices of ammonium nitrate, urea and phosphate fertilizers were 79 percent higher in 2022 than their international equivalents in 2019 and 2020.

Figure 2: Fertilizer and natural gas price indices (base year is 2010)

The more structural cause of this abrupt increase in the price of fertilizer is the war in Ukraine, which started in February 2022. Russia and Ukraine are major suppliers of fertilizers and African countries import a significant portion of their fertilizers. Both countries accounted for 37 percent, 17 percent and 14 percent of Africa’s potassium, nitrogen and phosphorus imports respectively in 2019. The Ukraine war disrupted industrial activities and logistics in Ukraine. In Russia, meanwhile, Western sanctions imposed after Russia’s invasion also disrupted that country’s fertilizer supplies. Belarus, a significant supplier of potash to Africa, is also under sanctions similar to those slapped on Russia.

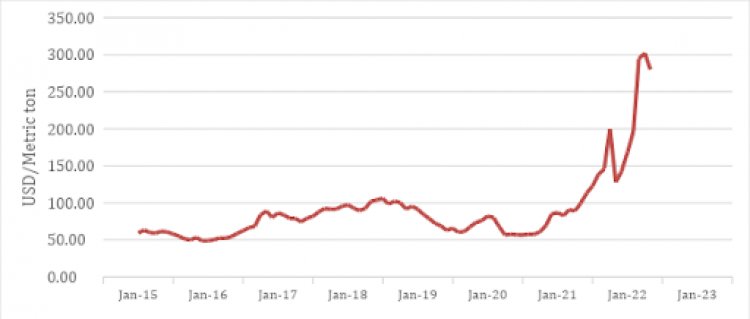

An important proximate cause of the fertilizer price hike has been the increase in the cost of fertilizer inputs. The major input for ammonia-based fertilizer is natural gas, which has seen its price go up significantly since September 2021 (Figure 3). Another significant input is coal, which is used in producing Chinese-made ammonia-based fertilizer. Its price has also increased significantly since 2021 (Figure 3). In addition, the price of oil, an all-important major industrial input, has also gone up significantly over this period.

Figure 3: Price of South African Coal

III. Impact of Rising Fertilizer Prices

The spike in fertilizer prices is a major concern because of the effect it has on food prices across Africa. This increase predates the breakout of war in Ukraine, and dates back to the start of last year’s rainy season in Africa's northern hemisphere. The Ukraine crisis is likely to have an adverse effect on harvests across the continent later this year. Already, Africa's use of chemical fertilizer is low even when compared to other developing regions in Latin America and South Asia. A drastic increase in the price of fertilizers is bound to drastically depress its use on the continent even more, with corresponding effect on crop yields. The World Food Programme estimates that cereal production in East Africa will fall by about 16 percent this year. With lower domestic supply, increased pressure on local food prices can be expected.

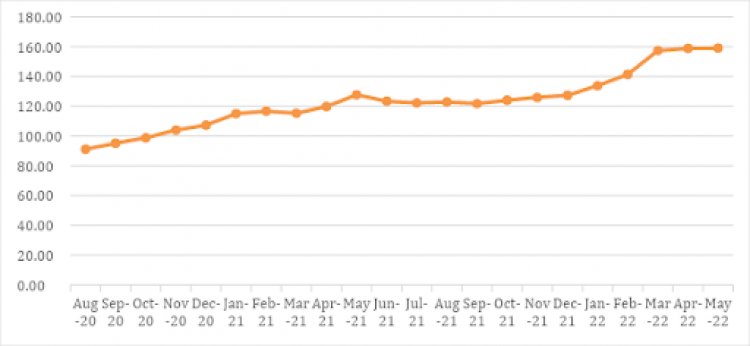

Under normal circumstances, one could hope that lower domestic production of food crops can be offset with increased imports. Unfortunately, the current crisis is a shock on a global scale. As a result, food prices have been on a steady rise this year (Figure 4). Part of the increase is the effect of the Ukraine war on the country’s wheat exports, which is being compounded by the high price of fertilizer effect on other wheat producers.

Another major cereal that has been affected by the increase in the price of fertilizer is rice. While neither Ukraine nor Russia are major rice exporters, the combined effect of rising input costs and cross-price effects are contributing to the appreciation of the global price of rice. This means that a further increase in overall food prices can be expected, and the effect will be acutely felt in Africa.

Figure 4: Food price index (base year is 2010)

IV. Long Term Policy Response

The affordability of fertilizer in African countries has been a longstanding policy concern. Crop yields on the continent are significantly lower than in other regions of the world, and low fertilizer usage is a major contributing factor. When shocks like the Ukraine war jolt the system, the traditional response has typically been to subsidize inputs and food. These short-term measures are needed to avoid a bigger food crisis. While these fertilizer subsidies programs have led to a boost in fertilizer use in many countries, and forestalled larger food crises, they do not address the underlying causes of higher input costs. And as long as high fertilizer costs remain, the standard policy responses of input subsidies are not a long-term policy fix, given the fiscal implications of such schemes, particularly for a region with many countries in or close to debt distress.

The continent is not without the means to address the long-term solutions to the fertilizer problem. The answer lies in industrialization in order to boost local fertilizer manufacturing. At a technical level, what is needed are the feedstock for the fertilizer and energy requirements for the industrial processes. The main ingredients for major fertilizer types are present in Africa. These include natural gas and coal, which are the feedstock for nitrogen-based fertilizers such as urea and di-ammonium phosphates. As Table 1 shows, the continent has a significant deposit of natural gas. Coal is another major input for urea fertilizer, which is produced in significant amounts in several African countries including Niger, Nigeria and South Africa. Another significant ingredient is phosphate rock, which many African countries possess in abundance. It should be acknowledged that fertilizer manufacturing is energy-intensive, and the continent faces considerable challenges with high energy costs. That challenge underscores the fact that addressing the cost of fertilizer must be part of a broader industrial development policy.

Table 1: Proven Natural Gas Reserves of African Countries

| Country | Trillion Cubic Feet |

| Nigeria | 206 |

| Algeria | 159 |

| Senegal | 120 |

| Mozambique | 100 |

| Egypt | 77 |

| Tanzania | 57 |

| Libya | 53 |

| Angola | 13.5 |

| Republic of Congo | 10 |

| Equatorial Guinea | 5 |

References

African Union, Africa Fertilizer Financing Mechanism, United Nations Economic Commission for Africa. 2019. “Promotion of Fertilizer Production, Cross-border trade and consumption in Africa”, Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire.

Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. 2020. South African Fertilizer Market Analysis Report, Pretoria, South Africa.

Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO). 2019. Rome, Italy.

Hebebrand, C. and D. Laborde. 2022. "High fertilizer prices contribute to rising global food security concerns", International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). Blogpost.

Smale, M. and V. Theriault. 2018. “A Cross Country Summary of Fertilizer Subsidy Programs in sub-Saharan Africa”, Food Security Policy Research Papers, Michigan State University.

World Bank. 2022. "The Impact of the War in Ukraine on Commodity Markets", Washington DC.

World Bank. 2022. “Commodity Prices”, Washington, DC.

World Food Programme. 2022. “Fertilizer Price Impact on 2022 Cereal Production in Eastern Africa”, Rome.

About the Author

Dr. Ousman Gajigo is the manager of the Microeconomic, Institutional and Development Impact Division in the Research Department of the African Development Bank. Before holding this position, he founded and managed an agribusiness firm and served as a consultant between 2015 and 2019. Before that, he worked at the World Bank and Columbia University. He holds a PhD in development economics from the University of Wisconsin–Madison. He has research experience in entrepreneurship, labour market, agricultural economics, natural resources, and economics of education.