This article is part of the BRICS thought leadership series, published by APRI in collaboration with the University of Johannesburg. It explores key themes from the 16th BRICS Summit and the group's broader initiatives. The series is edited by Ada Mare, Bhaso Ndzendze, Serwah Prempeh.

Background

The literature on the New Development Bank (NDB) can be divided into three groups: analyses of the bank's impact on global governance, comparisons of its normative and operational aspects with other multilateral development banks (MDBs), and a focus on its main financing characteristics.

In recent years, the analysis of the NDB's emergence, characterisation and financial scope within the debate over a new international financial architecture (IFA) which acknowledges the needs of emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs) (Shelepov, 2016; Schulz, 2018) has gained importance in academic and political circles. Some authors argue that, while the emergence of this bank indicates a demand for greater participation of the BRICS bloc in global economic governance institutions (Vadell, 2021), it does not represent a clear break from the guidelines of existing traditional MDBs (Moreira-Junior and Figueira, 2014; Wang, 2017). Others add that its emergence does not imply the creation of an alternative order (Carvalho et al., 2015; Qobo and Soko, 2015), but that the creation of the NDB has shifted the IFA for development towards institutions dominated by developing countries (Griffith-Jones, 2015).

The second group of the literature compares the NDB with the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), mainly in response to China's active role through these institutions. This comparison promotes an ambiguous model of different traditions of global financial governance (Mazenda and Newadi, 2016; Wang, 2019). A third set of authors analyses the normative, instrumental and operational aspects of the bank (Wang, 2017; Cooper, 2017; Molinari and Patrucci, 2020; Duggan et al., 2022). In this context, over the past ten years the comparative analyses between the NDB, the World Bank and other regional development banks have proliferated (Chin, 2014; Wang, 2017; Reisen, 2015; Shelepov, 2016; Ella, 2021). Regarding the financing provided by the bank, Bradlow and Masamba (2023) assess the bank's presence in Africa and its expansion possibilities, while Molinari et al. (2021) analyse its first five years of operations, operational policies and key financing instruments. Finally, Chin (2024) highlights the achievements of its first decade of existence, focusing on the evolution of a research agenda and academic debates within the NDB.

However, no studies analyse the bank's general strategies and the actual financing provided to its (sovereign and non-sovereign) borrowers. Therefore, this study aims to give a first glance at the NDB's financial policy alignment with its institutional strategies. To do so, we propose a simple comparison between the bank's two general strategies (2017-2021; 2022-2026) with its actual lending. Our analysis begins when the institution started operating in 2016 and ends in 2023. Since the NDB presents itself as an expression of the growing role of the BRICS and other emerging market and developing countries (EMDCs; NDB, 2017b), we wonder to what extent the NDB has implemented its general strategies, especially in terms of its attention to the non-sovereign borrowers, priority sectors and local currency financing.

This research is relevant given the changes occurring at the international level, such as the Russia-Ukraine and Israel-Hamas conflicts, which have reconfigured the leadership among the BRICS countries.1 On one hand, this was reflected in the recent admission of NDB-member, oil-producing countries, such as Egypt and the United Arab Emirates. This expansion is accompanied by the acceptance of Ethiopia, Iran and Saudi Arabia to the BRICS bloc and is driven by China and Russia in opposition to Brazil and India. It aims to enhance the significance of BRICS as a strategic and financial geopolitical partnership (Optenhögel, 2024). On the other hand, these changes have an impact on the functioning of the NDB. The 2024 BRICS Summit took place in Russia, a country banned from NDB funding since 2022 (NDB, 3 March 2022). Moreover, other recent and potentially disrupting facts are the ongoing geopolitical leadership disputes between India and China, as well as the efforts of some members, such as South Africa and India, to balance their political conflicts with the West with the significant foreign direct investments in their territories (Pascual, 17 August 2023).

This analysis of the NDB's operations should enable us to understand whether the disputes within and outside the BRICS bloc will have an impact on the bank's financing and, hence, on the BRICS countries’ development. In this sense, it is important to highlight that this article is part of a research agenda which studies the conditionalities and regulations imposed by the two MDBs most recently created to assist developing countries in advancing their energy transition. In the following section, we describe the NDB's strategic guidelines and then contrast them with actual lending, using a database with all the projects approved2 by the bank over the period 2016-2023. We focus on the type of financing, the currency and the sector for each loan.3 The fourth and last section contains some general recommendations.

The New Development Bank: Scope and main features of a new International Financial Architecture

The rise of emerging powers in their contest for participation within the international order can be situated between the global financial and climate governance crises (Petrone, 2019). The grouping of the main EMDEs in the BRICS bloc and the deployment of their ‘collective financial statecraft’4 (Katada et al., 2017) responds to the frustration of developing economies in general, and emerging ones in particular, with the slow pace of reforms in the Bretton Woods institutions following the 2008 international financial crisis. Notably, the bloc highlights its low representation level and the conditionalities imposed through financing and agenda-setting by these institutions on the domestic policies of borrower countries, with a direct impact on their need to finance their economic growth (Griffith-Jones, 2014; Wang, 2019; Vadell, 2021).

Although there are tensions regarding EMDEs’ binding commitments and national interests concerning multilateral climate agreements, in international fora the BRICS group has shown a willingness to support climate governance reform initiatives (Mukhia et al., 2024), at least from the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Copenhagen (COP15) onwards. Aware of their dependency on fossil fuels for industrial production (Viola and Basso, 2016) and, given that as a bloc they generate 42% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, the BRICS countries have promoted the implementation of the Paris Agreement (COP21). They have also called for an increase in the mobilisation of financial resources from developed countries to those in development in order to sustain their development processes and advance climate change policies (Molinari and Patrucchi, 2020). More recently, at COP26 (2021) and COP28 (2023), this demand was complemented by an ambitious long-term goal: reducing the use of fossil fuel-based energy and helping developing countries implement their own energy transitions (Petrone, 2019; United Nations, December 13, 2023).

In this context, the New Development Bank (NDB) and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) emerged, both with headquarters in Shanghai, China. These banks were created as instruments through which emerging powers sought to complement the existing financial efforts of multilateral and regional financial development institutions such as the World Bank Group or the Inter-American Development Bank. Additionally, they aimed to influence both multilateral agendas and the IFA (BRICS, 2012; Mzukisi and Soko, 2015; Wang, 2017, 2019; Molinari and Patrucchi, 2020; Molinari et al., 2021).

India proposed the creation of the NDB in 2009 during the fourth BRICS summit. Two years later, at the sixth BRICS summit in Fortaleza, its Articles of Agreement were approved. In 2015, the bank held the first meeting of its Board of Directors, and, in 2016, it became fully operational during the eighth BRICS Summit. Broadly, this bank aims to be ‘new’ in three aspects: relationships, projects and innovative instruments, as well as flexible and non-bureaucratic when it comes to project review and implementation (NDB, 2017b, p. 3). In particular, the NDB seeks to meet its member countries' demands without undermining their political sovereignty, featuring a non-resident Board of Directors and employing a consensual internal governance model. Finally, like most MDBs, the NDB aims to include among its financing instruments guarantees, syndicated loans with private investors, equity investment and project bonds (Wang, 2017 and 2019; Molinari and Patrucchi, 2020; Molinari et al., 2021).

The NDB's mandate is to mobilise resources for infrastructure and sustainable development projects that promote a green economy in its member countries (NDB, 2016 and 2017a; Molinari et al., 2021). It aims to achieve this by financing projects (both sovereign and non-sovereign) that incorporate economic, environmental and social criteria in their design and implementation. To do so, it aims to reach 30% of its financing for non-sovereign borrowers by 2026. Moreover, as part of its learning process, the bank modified its mandate in terms of sectors. While its general strategy (2017-2021) aimed to allocate about two-thirds of its financial commitments to sustainable infrastructure – showing flexibility to include traditional infrastructure projects – the current strategy (2022-2026) refined this goal by committing to allocate 40% of the total approval volume to those projects that contribute to climate change mitigation and adaptation and to support member countries' transition to sustainable development (NDB, 2017b and 2022). This change may have impacted the institution's definition and selection of priority sectors.

Finally, given that the NDB emphasises the need to increase its local currency financing to avoid exchange rate risks for its borrowers (aiming at a 30% target for 2026), it is worth mentioning its successful issuance of the first Green Financial Bond in China's Interbank Bond Market in 2016. However, this local currency financing poses at least two challenges for the bank: (i) It limits the possibilities of attracting private financing for these projects due to their relatively low profitability and risk mitigation difficulties, and (ii) it restricts the expansion of thematic bond offerings and local currency financing, potentially deepening capital markets in its member countries and challenging the commitment to allocate 30% of financing in local currency (NDB, 2022). In summary, in its second strategy, the bank expanded the definition of its mission, committed to increasing both local currency and non-sovereign financing and redefined its priority sectors for financing.

Contrasting the NDB’s strategies with its project financing

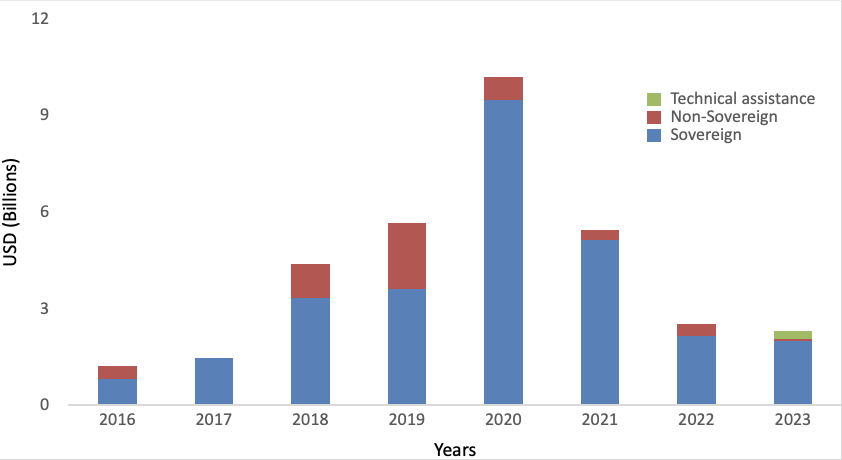

In this section, using a database with all the projects approved by the NDB over the period 2016-2023, we analyse the alignment of the mentioned NDB strategies with its project financing. First, regarding the type of financing, the bank committed to funding 30% for the private sector by 2026. However, until 2023, most of the bank’s financing was approved for sovereign guarantee projects (see Figure 1), accounting for 84.3% of the total (USD 28 billion for 70 projects). In contrast, from 2016-2023, financing for projects without sovereign guarantees totalled almost USD 5 billion, which was concentrated in 23 projects (nearly 15% of the total financing).5 This may be because NDB's lending rates are not as competitive as its AAA-rated peers (NDB, 2024), a fact that has a greater impact on non-sovereign operations which pay market interest rates. Both types of financing followed an increasing trend until 2020 when sovereign financing increased significantly as non-sovereign financing declined. Following the post-pandemic recovery, both categories grew but did not recover the amounts allocated before 2020. Furthermore, since 2023, there has also been a significant drop in financing for the private sector (which fell from USD 350 million to USD 50 million in one year). In this regard, the NDB is not exempt from the challenges faced by private financing for development in EMDEs (Inderst, 2021). Together with the fact that the pandemic year was atypical for most MDBs, the committed increase in non-sovereign lending may have also been hindered by the nascent development of co-financing instruments, the fact that most members seeking financing have immature capital markets and the bank's delay in designing a new financial model (NDB, 2024),. In this regard, the NDB will need to double the proportion allocated to non-sovereign projects within three years or strengthen its role as a broker by mobilising more private funds.

Source: Own elaboration based on NDB's project database.

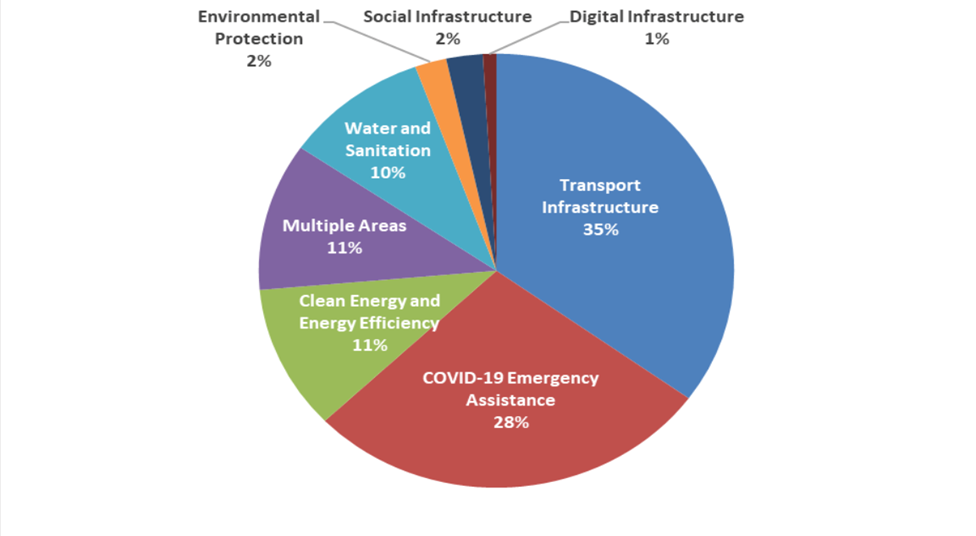

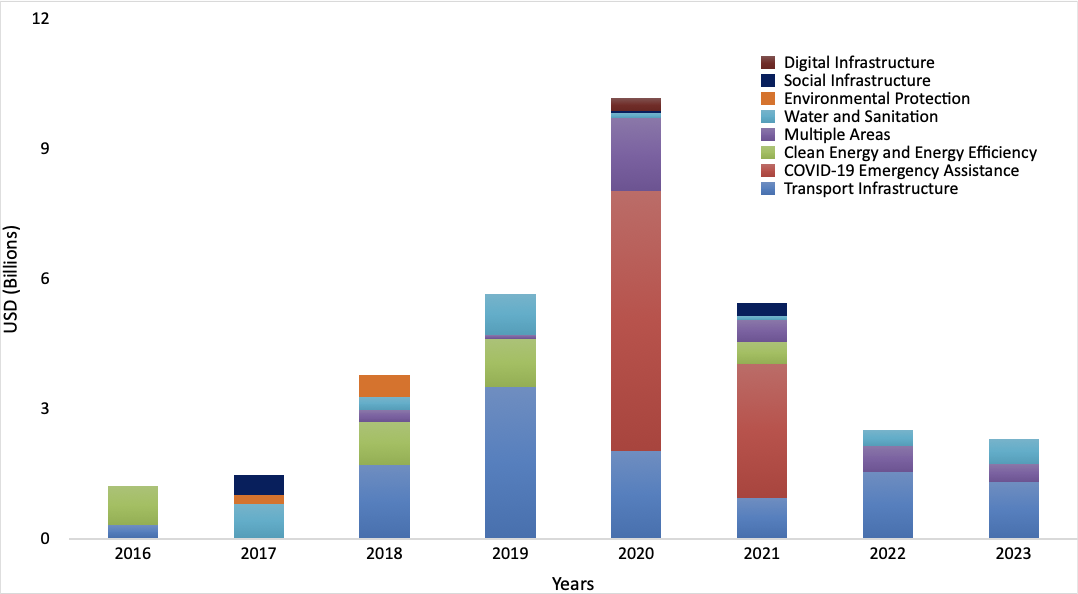

Second, without emphasising the exceptional financing to alleviate the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic,6 the main sector receiving funding up to 2023 was ‘transport infrastructure’,7 with approvals for USD 11 billion, accounting for 35% of the total (34 projects; see Figures 2 and 3). Following this was ‘multiple areas’8 with 11% of the total (approximately USD 3.6 billion for 17 projects). The next is ‘clean energy and energy efficiency’, with about USD 3.5 billion (almost 11%, 13 projects), followed by ‘water and sanitation’ (10%, USD 3.2 billion, 14 projects). Notably, during the two years of projects to combat the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic (2020 and 2021), all sectors saw a decrease in their funding volume, except for an increase in ‘multiple areas’. On the other hand, during 2023 and 2024, only ‘multiple areas’, ‘transport infrastructure’ and ‘water and sanitation’ sectors received funding. However, they did not recover the amounts received before the pandemic. This result may be partly attributed to the significant impact of the pandemic on the founding NDB members, thus affecting the speed of acquiring, processing and implementing new projects in general (NDB, 2024).

In this regard, the fact that there are eight proposed projects awaiting approval in the ‘clean energy and energy efficiency’ category, along with the limited flows directed towards ‘environmental protection’, highlights the challenges faced by the bank: It has just three years to allocate greater funding towards sectors that will enable its members to promote climate change adaptation and/or mitigation policies.

Source: Own elaboration based on NDB's project database.

Source: Own elaboration based on NDB's project database.

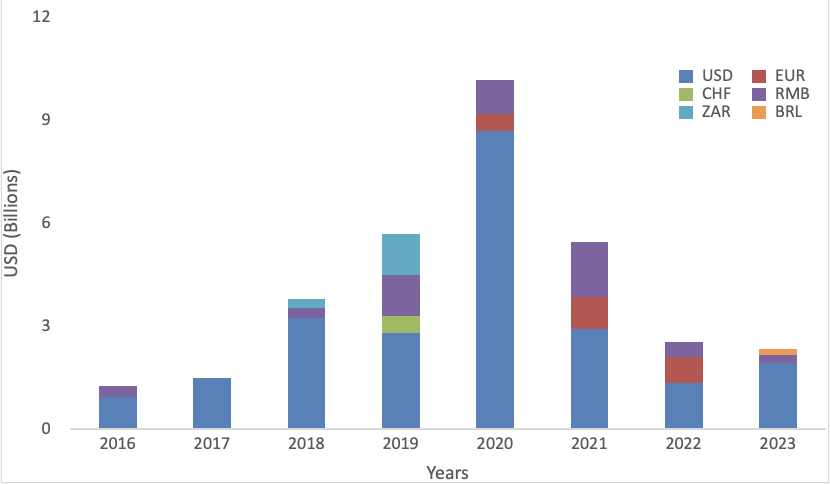

Source: Own elaboration based on NDB's project database.

Finally, as shown in Figure 4, by 2023, over three-quarters of the financing provided by the NDB was in ‘hard currency’ (USD, Euro, Swiss Francs [CHF]), which puts into tension one of the main aspects that distinguishes the bank: financing in local currency. This figure means that only one-fifth of the approved financing was granted in local currency (21 projects totalling USD 13 billion). It is also noteworthy that the financing provided by the Bank in RMB accounted for 15% of the total (USD 5 billion for 15 projects), in stark comparison to the other local currencies. Moreover, this financing has declined since 2021. The other two currencies in which the bank lent (Brazilian reals [BRL] and South African rand [ZAR]) represent a much smaller proportion of the total. Hence, the bank still needs to increase its lending to local currencies by about ten percentage points if it is to meet its 30% target for 2026.

Recommendations

To adapt to the global challenges posed by the consequences of climate change (among other things), the NDB has expanded its original mandate to finance projects for climate change mitigation and adaptation. However, the bank still faces significant challenges regarding its commitments. These are related to increasing financing in local currency and non-sovereign financing, as well as strengthening financing for sectors and activities combating climate change.

Specifically, the bank needs to increase the proportion allocated to non-sovereign projects and/or strengthen its role as a broker by mobilising more private funds. In addition, the NDB must strengthen its lending to local currency – one of its distinctive aspects vis-à-vis most MDBs – and help countries to diversify their monetary reserves. This will foster developing countries' capital markets and relieve those external constraints which exacerbate external debt problems and budgetary restrictions. However, while the NDB's financing could mask its members' external debt problems, it is unlikely to have a leading role in developing countries' debt restructuring processes.

Finally, in light of the recent geopolitical and geoeconomic challenges facing the BRICS countries, diversifying the NDB's funding and doubling funding towards energy transition-related sectors may enable the bank's members to promote both climate change adaptation and the mitigation of national policies. This will ensure a more sustainable energy supply and safety strategy that allows them to develop. In this context, the NDB members are expected to increase financing towards sectors such as ‘clean energy and energy efficiency’ and ‘environmental protection’. On the other hand, we expect that at the upcoming BRICS 2024 Summit, the bank will develop its own climate change and energy transition strategy, detailing the activities it will finance and the financial instruments it will offer to developing countries to address these global challenges.

References

Bradlow, D. D., & Masamba, M. (2023). The New Development Bank in Africa: Mid-term evaluation and lessons learned. Global Policy, 15(2), 427-433. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.13310

Carvalho, C. E., Daldegan de Freitas, W., Canoa, L., de Godoy, N., & Gomes, F. (2015). O banco e o arranjo de reservas do BRICS: iniciativas relevantes para o alargamento da ordem monetária e financeira. Estudos Internacionais, 3(1), 45-70. https://periodicos.pucminas.br/index.php/estudosinternacionais/article/view/10062

Chin, G. (2014). The BRICS-led Development Bank: Purpose and Politics beyond the G20. Global Policy, 5(3), 366-373. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12167

Chin, G. (2024). Introduction – The evolution of New Development Bank (NDB): A decade plus in the making. Global Policy, 15(2), 368-382. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.13399

Cooper, A. F. (2017). The BRICS’ New Development Bank: Shifting from Material Leverage to Innovative Capacity. Global Policy, 8(3), 275-284. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12458

Duggan, N., Ladines, J. C., & Rewizorski, M. (2022). The structural power of the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) in multilateral development finance: A case study of the New Development Bank. International Political Science Review, 43(4), 495-511. https://doi.org/10.1177/01925121211048297

Ella, D. (2021). Balancing effectiveness with geo-economic interests in multilateral development banks: The design of the BAII, ADB and the World Bank in a comparative perspective. The Pacific Review, 34(6), 1022-1053. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09512748.2020.1788628

Griffith-Jones, S. (2014). A BRICS Development Bank: A Dream Coming True? UNCTAD Discussion Papers, 215, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. https://ideas.repec.org/p/unc/dispap/215.html

Griffith-Jones, S. (2015). Financing global Development: The BRICS New Development Bank. Briefing Paper, (13). Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE), Bonn.

Inderst, G. (2021). Financing Development: Private Capital Mobilization and Institutional Investors. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3806742

Katada, S., Roberts, C., & Armijo, L. (2017). The Varieties of Collective Financial Statecraft. Political Science Quarterly, 132(3), 403-433. https://doi.org/10.1002/polq.12656

Mazenda, A., & Newadi, R. (2016). The rise of BRICS development finance institutions: A comprehensive look into the New Development Bank and the Contingency Reserve Arrangement. African East-Asian Affairs, (3), 96-123. http://dx.doi.org/10.7552/0-3-178

Molinari, A., & Patrucchi, L. (2020). Rompiendo el molde: logros y desafíos de los nuevos bancos de desarrollo. Ciclos En La Historia, La Economía Y La Sociedad, 54, 131-155. https://ojs.econ.uba.ar/index.php/revistaCICLOS/article/view/1748

Molinari, A., Patrucchi, L., & Flores, C. (2021). ¿Qué financian los nuevos bancos de desarrollo? Una aproximación a sus operaciones durante su primer quinquenio de actividad. Serie Documentos de Trabajo del IIEP, (67), 1-23. https://ojs.econ.uba.ar/index.php/DT-IIEP/article/view/2514

Moreira Junior, H., & Figueira, M. S. (2014). O Banco dos BRICS e os cenários de recomposição da ordem internacional. Boletim Meridiano 47, 15(142), 54-62. ISSN 1518-1219

Mukhia, A., Shen, Q., & Xiaolong, Z. (2024). Climate Governance Pathway for BRICS in the Post-Paris Era. Global Journal of Emerging Market Economies, 16(3), 321-339. https://doi.org/10.1177/09749101241244456

New Development Bank (NDB; 2016). Annual Report 2016.

New Development Bank (NDB; 2017a). Annual Report 2017.

New Development Bank (NDB; 2017b). NDB’s General Strategy: 2017–2021.

New Development Bank (NDB; 2020). Annual Report 2020.

New Development Bank (NDB; 2022). New Development Bank General Strategy for 2022–2026. Scaling Up Development Finance for a Sustainable Future.

New Development Bank (NDB; 2022, March 3). A Statement by the New Development Bank.

New Development Bank (NDB; 2024). Evaluation Synthesis Report. Preliminary Experience in Establishing NDB on the Ground Presence. The Role of Regional Offices.

Optenhögel, U. (2024). BRICS: de la ambición desarrollista al desafío geopolítico. Nueva Sociedad, 310. ISSN: 0251-355. https://nuso.org/articulo/310-BRICS/

Pascual, M. (2023, August 17). The BRICS bloc is riven with tensions. The Economist. https://www.economist.com/international/2023/08/17/the-brics-are-getting-together-in-south-africa

Petrone, F. (2019). BRICS, soft power and climate change: new challenges in global governance? Ethics & Global Politics, 12(2). https://doi.org/10.1080/16544951.2019.1611339

Qobo, M., & Soko, M. (2015). The rise of emerging powers in the global development finance architecture: The case of the BRICS and the New Development Bank. South African Journal of International Affairs, 22(3), 277-288. https://doi.org/10.1080/10220461.2015.1089785

Reisen, H. (2015). Alternative multilateral development banks and global financial governance. International Organisations Research Journal, 10(2), 106-118. http://www.brics.utoronto.ca/biblio/iorj-2015-02-reisen.pdf

Schulz, J. (2018, November 14-16). La construcción de un nuevo sistema monetario y financiero mundial. Del BAII y el Banco BRICS al petro-yuan-oro. [Conference presentation]. IX Congreso de Relaciones Internacionales, La Plata, Argentina. https://www.memoria.fahce.unlp.edu.ar/trab_eventos/ev.16999/ev.16999.pdf

Shelepov, A. (2016). Comparative Prospects of the New Development Bank and Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. International Organisations Research Journal, 16(4), 700-716. http://dx.doi.org/10.17323/1996-7845-2016-03-132

United Nations (UN). (2023, December 13). Secretary-General's statement at the closing of the UN Climate Change Conference COP 28. (Accessed: 15 August 2024).

Vadell, J. (2021). O BRICS reset num mundo multipolar? Conjuntura Internacional, 18(1), 45-49. https://periodicos.pucminas.br/index.php/conjuntura/article/view/27283/19102

Viola, E., & Basso, L. (2016). Wandering decarbonization: the BRIC countries as conservative climate powers. Revista Brasileira de Política Internacional, 59(1). http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0034-7329201600101

Wang, H. (2017). New Multilateral Development Banks: Opportunities and Challenges for Global Governance. Global Policy, 8(1), 113-118. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12396

Wang, H. (2019). The New Development Bank and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank: China’s Ambiguous Approach to Global Financial Governance. Development and Change, 50(1), 221–244. https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12473

[1] This is what Standard & Poor’s calls ‘agency risk’, and is one of the main reasons behind the NDB's AA+ (i.e. suboptimal) credit rating.

[2] We only consider those projects under implementation or closed, excluding the ones proposed and cancelled.

[3] This database was created for an orientated research project named ‘Multilateral financing for energy transition initiatives’, financed by the Argentinian Central Bank and the CONICET. It contains, for each loan (among other fields): sector, country, date of approval, type of financing, status of the loan, currency and amount financed by the Bank (loans financed in local currency were converted using the International Financial Statistics’ monthly average exchange rate).

[4] That is, the BRICS' collective quest for greater influence and autonomy to gain structural power within financial institutions.

[5] The total is complemented by one technical assistance approved in 2023 for USD 252 million (0.8%).

[6]The ‘COVID-19 Emergency Assistance’ financing represented 28% of the total, with almost USD 9.1 billion during the years 2020 and 2021.

[7] The analysed database uses the sectoral categorisation provided by the NDB on its official site, which broadly aligns with the proposal in the current strategy (2022-2026), adding two sectors not specified in that strategy: ‘multiple areas’ and ‘COVID-19 Emergency Assistance’.

[8] This sector includes on-lending and investment through financial intermediaries with sub-projects in key areas of NDB's operations (NDB,2020, p.8).

About the authors

Andrea Molinari

Andrea Molinari is a researcher at CONICET/CEED-EIDAES-UNSAM and teaches international economics at Buenos Aires University (UBA). She holds a PhD in Economics from the University of Sussex. At EIDAES-UNSAM, she coordinates both the Center for Economic Development Studies (CEED) and the “Study Programme on Energy Transition. Challenges for Innovation, Development and Funding”.

Rocío Ceballos

Rocío Ceballos is an advanced student in the Master’s programme in Economic Sociology, Interdisciplinary School of Advanced Social Studies at National University of San Martin (EIDAES-UNSAM). She is also a PhD candidate at the National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET, Argentina) and the Centre for Development Economics Studies (CEED-EIDAES-UNSAM).