The European Green Deal and the African Private Sector

The European Green Deal (EGD) is a long-term policy initiative defining the European Union’s strategy towards a green economy by 2050. As a policy instrument, the EGD is primarily intended for the domestic EU audience, but the potential it entails has global implications - with possible benefits for Africa and its private sector.

This study was produced by APRI – Africa Policy Research Institute (APRI) – a Berlin-based independent, non-partisan African policy institute researching key policy issues affecting the African continent, in collaboration with AfricaRising GmbH, a boutique consultancy focusing on market access. The funding for the work was provided by the Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom (FNF).

Many thanks to Alexander Demissie, Managing Director of AfricaRising, and Dr. Olumide Abimbola, Executive Director of APRI, for leading the production of this study. We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Nora Chirikure, APRI Junior Fellow.

We also thank Chigozie Nweke-Eze (Integrated Africa Power) and Teniola Tayo for gracefully peer-reviewing the study and offering valuable improvements to the document. Our gratitude also goes to Jordi Razum (FNF) and Isabella Roberts (APRI) for their support to the project.

Summary

The European Green Deal (EGD) is a set of long-term policy initiatives defining the European Union’s (EU) climate strategy to reach net zero emissions by 2050. It is therefore an all encompassing framework guiding the EU’s development pathway over the next decades. This guiding function implies that the EGD is not only of significance to the EU’s Member States but also to its partner countries. African countries, and in particular their private sectors, should strive to benefit from the EGD and its vast support structure.

This paper starts by highlighting the increasing strategic importance Africa plays in allowing the EU to realize its EGD, with a focus on Africa’s potential to supply the renewable energy and minerals required for the EU to achieve its net-zero targets. This supply includes green hydrogen and the minerals needed for scaling up electric mobility and renewable energy generation and storage technologies in Europe.

The paper then showcases opportunities the EGD offers the African private sector and how available finance and support for technology development and transfer and capacity-building can be utilized in this regard. Three types of access to the EGD are identified, including support that African companies can access: independent, in cooperation with European partners or by establishing a subsidiary company within the EU. Based on the findings of this paper, the following four recommendations are offered on how to enhance opportunities for the African private sector to benefit from the EGD:

- Sector-specific analysis by African companies: As part of their business development and internationalization efforts, African companies should analyze the EGD and its support structure to identify concrete ways for their respective business sectors to use the EGD to their advantage. These possibilities may include co-financing for technology upgrades that increase local value creation or support in establishing European subsidiaries and trade facilitation.

- Proactive engagement by African governments: African governments should actively engage their European counterparts in identifying opportunities for the African private sector under the EGD. This engagement is particularly relevant for African countries that have comparative advantages regarding the establishment of low-emission supply chains due to a high share of renewable energy in the national energy mix or their renewable energy resource endowments.

- Private sector partnership development by the EU: The EU should foster partnerships between businesses in Africa and Europe that contribute to realizing the EGD, in agriculture, manufacturing and green hydrogen. This fostering should include match-making activities that result in developing or expanding supply chains and the establishment of joint ventures between African and European partners in both regions.

- Further research by EU and African institutions: Building on this paper and other existing literature on this topic, EU and African research institutions and business associations should conduct further research and analysis on the opportunities that the EGD offers for enhancing commercial links and supply chains between the African continent and the EU. It is paramount that African governments and private sector decision-makers understand the EGD thoroughly in order to increase existing opportunities through targeted bilateral negotiations with EU countries and to trigger initiatives that will increase knowledge and technology transfer from Europe towards African countries.

Introduction

The European Green Deal (EGD) is a long-term policy initiative defining the European Union’s (EU) strategy towards a green economy by 2050. In its entirety, it provides a set of plans and visions for the EU’s transition towards a low-carbon economic growth strategy. As a policy instrument, the EGD is primarily intended for the domestic EU audience; however, the potential it entails has global implications - with possible benefits for Africa and its private sector. In addition, the EGD and its specific policies, regulations and measures will impact the EU’s trading relationship with third-country partners, including African countries. As the EGD continues to accelerate the creation of new financial sources, technology transfer and partnership opportunities, it is paramount that African private sector stakeholders understand how to utilize these opportunities to benefit their own development.

At the EU-Africa Green Investment Forum in April 2022, the President of the African Development Bank, Akinwumi Adesina, warned that investors “cannot ignore Africa” and that “the recovery must ensure more space for the private sector in order to reduce state debt and foster inclusive growth”.1 As capital prospects are augmented by extra-regional actors such as the EU, Adesina’s words particularly highlight that the EU’s move towards a green economy is seen favorably in African countries as it opens new opportunities for Africa-EU private sector collaboration. By including the private sector, African decision-makers understand that sustainable development and green technologies can help African countries tackle climate change and provide their domestic companies with a commercial niche to harness.

At the same time, it is also well understood that, through the EGD, the EU will primarily promote its own interests, including strengthening its supply chains, the vulnerability of which became apparent during the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, after the Russian war on Ukraine erupted, the need for diversification of energy sources has increased dramatically. Africa’s proximity to Europe as well as the African continent’s potential for wind, solar, geothermal and hydroelectric power2 have become important in the considerations of the EU and its private sector players to involve the African public and private sector in the EU’s future energy security structure. An example of this can be seen in the recent signing of a “green partnership” deal between the EU and Morocco.3 These new developments can be instrumental in the African private sector acquiring increased motivation and interest to engage in close collaboration with EU institutions and companies. New projects such as the EU-backed Hydrogen Accelerator,4 aiming to create a €100 billion value chain and development of infrastructure, storage, facilities and ports, offer opportunities for the African private sector to cooperate.5

Through initiatives such as the Global Gateway , European leaders have expressed their intention to build an “equal partnership” with Africa". In addition, there are increasing discussions about how the EGD can strengthen Africa’s and Europe’s economies through Europeans working in joint ventures with African firms. In assessing these developments, this policy report explores the strategic importance of African countries and their private sector stakeholders for the EGD. In addition, it analyzes the opportunities the EGD offers to Africa’s private sector and evaluates any existing modalities for accessing the EGD as well as highlighting examples of African technology solutions that already play a role in the EU green transition trajectory.

Strategic importance of Africa for the European Green Deal

The global move away from fossil fuels is well under way, with the effects going beyond climate and environment - they are also geopolitical. Through the EGD, the EU is working to establish a low-carbon economy emphasizing sustainable development in its Member States. As such, changes in the EU economy, governance and foreign policy could impact African countries.

The EGD is also an adjustment to an increasingly changing global geo-strategic and geo-economic situation. Today, it is not certain that Europe will play a primary role in the new development trajectory emerging on the African continent. The colonial past is still shaping interactions between African and EU countries. French president, Macron, and Belgian president of the European council, Michel, for example, focused most of their pre-EU-AU 2022 summit diplomatic efforts on engaging with Francophone states, largely ignoring Anglophone African countries.8 Furthermore, some authors argue that competing national priorities within the EU lead to deadlock and an incoherent Africa policy9. At the same time, new emerging partners, such as Turkey10, and providers of South-South cooperation, such as China11, India12 and Brazil13, have been playing an important role in developing many African countries in the past decades, assuming technological and commercial leadership and accelerating development of closer cooperation with African decision-makers in the process. Particularly, the Russian war on Ukraine has highlighted the importance of the African continent to Europe: In 2021 alone, the EU imported 39.2% of its natural gas from Russia14, a supply that is now mostly cut-off due to war aggressions.

In addition, with a shrinking and aging population, the EU requires qualified workers to contribute to the green transitions by providing its labor market with the skills it needs. In particular, EU universities and research institutions are increasingly looking for new partnerships to boost the transition towards a green and digital economy in the EU through initiatives such as Horizon Europe15 and Erasmus +.16

In recent years, a plethora of multi-actor partnerships between the EU and African countries have proliferated.17 Partnerships such as the High-Level Policy Dialogue (HLPD) on Science, Technology and Innovation; the Africa-Europe Alliance for Sustainable Investment and Jobs; the Africa-EU Energy Partnership (AEEP); the G20 Compact with Africa (CwA) have been looking to increase the discussion on how investment and job creation can be realized on the African continent. In involving the private sector in areas such as health, digital, agriculture and sustainable food systems, platforms such as the Africa-EU Reference Group on Infrastructure (RGI) or Africa-Europe Foundation Strategy Groups have come to define the direction of the relationship, emphasizing innovation and sustainable investment in African countries.18 Furthermore, the African Union Green Recovery Action Plan19 and the unfolding of the African Continental Free Trade Area have increased the appeal of African countries for investment in sectors the EGD is supporting, such as clean and affordable energy, new technologies, finance and a circular economy

Through implementing the EGD, the EU is also trying to circumvent the vulnerabilities that are inevitably embedded in the transition to a digital and decarbonized economy. One such aspect is the increasing interest of European private sector players to diversify energy resources and alleviate the energy crisis in the EU by working closely with African countries and their private sectors in the development of Africa’s green hydrogen capacity. Due to the Russian war, energy vulnerability is now one of the biggest European concerns, and Europe seems determined to take action to reduce supply interruptions and the economic impacts they have on its economy and welfare.20 Especially high on the EU agenda are securing a reliable long-term energy supply source and diversifying strategy cooperations, among others with African countries.

Green Hydrogen

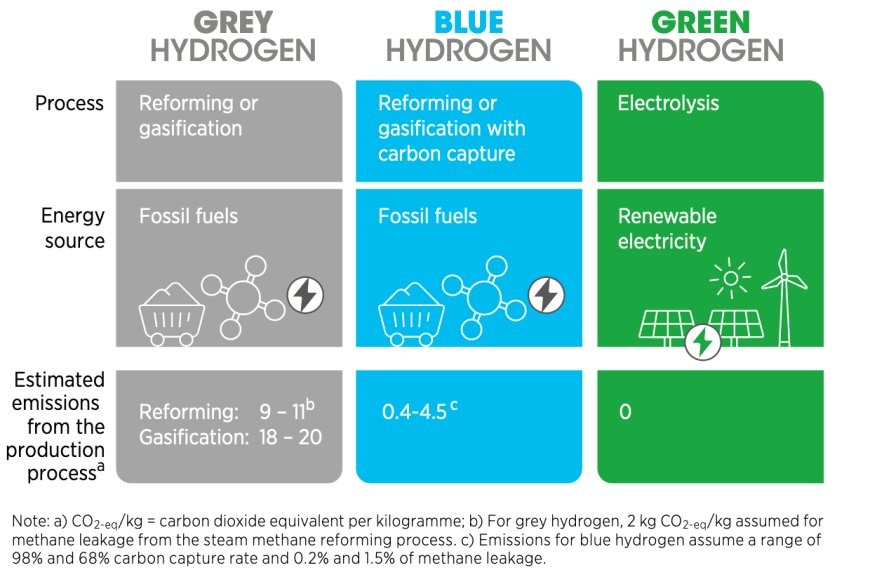

Green hydrogen is one of the cleanest forms of energy production, and African countries are looking to leverage hydrogen for both industrialization and decarbonization (see Figure 1). Meanwhile the EU is looking to reduce its carbon footprint through using green hydrogen.

Figure 1: Selected color-code typology of hydrogen production. Source: IRENA, 2022.21

As the cost of renewable energy, in particular solar energy, is falling, African countries with high solar energy potential are being spotlighted for green hydrogen production. In addition, green hydrogen production22 has the potential to increase the regionalization of energy relations among African players and the participation of more private sector actors on the continent.

In May 2022, Kenya, South Africa, Namibia, Egypt, Morocco and Mauritania launched the Africa Green Hydrogen Alliance to make the African continent the frontrunner in the race to develop green hydrogen.23 In order to provide institutional support, South Africa established the Hydrogen Society Roadmap, which should support the private sector in constructing a hydrogen ecosystem focused on research and innovation along with supply chain modernizations. In addition, Morocco is executing the Green Hydrogen Roadmap, has instituted a National Hydrogen Commission and plans to produce green ammonia, which is critical for the fertilizer industries25 currently facing a shortage globally.26 Furthermore, the Moroccan Solar Energy Agency is taking the lead in producing green hydrogen using Africa’s first industrial green hydrogen plant research platform.27 The EU and Egypt are also undertaking a Mediterranean Hydrogen Partnership that encompasses infrastructure development and grid construction. Namibia has also recognized the importance of green hydrogen and has launched a national Green Hydrogen Council and selected a dedicated Green Hydrogen Commissioner.28 A Namibian private sector entity, Hyphen Hydrogen Energy,29 is negotiating with the Namibian government to achieve an implementation agreement for its projected US$10 billion green hydrogen project, which will produce around 350 000 tons of green hydrogen annually for global and regional markets by 2030.

Acknowledging these opportunities and to increase trade and local supply chain development in African countries, EU countries, such as Germany, have extended engineering and investment activities focusing on the development of hydrogen resources on the African continent.30 Furthermore, in order to build the necessary strategic policy partnerships, the EU and the African Union plan to use the AEEP, which has been in place since 2007. The AEEP estimates that investment from Europe in green hydrogen in Africa could reach 75.6 billion Euros by 2030.31 Some countries in North Africa, including Egypt and Morocco, have a great potential to supply the EU with green hydrogen due to their geographical proximity, existing infrastructure and renewable energy industries.32 Additionally, plans under the EGD will likely benefit both the EU and African companies33 as hydrogen is poised to play an important role in long distance transportation.34 It is safe to say that ports will play a decisive role in creating the conducive environment for more hydrogen cooperation between European and African countries.35

Several institutional actors and forums have been established to forge ahead with building stronger partnerships within the EU and with the African private sector. Among them are the overarching EU “Hydrogen Strategy for a Climate-neutral Europe”,36 the European Network of Network Operators for Hydrogen (ENNOH) for “cross-border coordination”,37 the European hydrogen facility to “create investment security and business opportunities”, the Hydrogen Energy Network38 and the European Clean Hydrogen Alliance. Development of hydrogen programs are also supported under Horizon Europe, for example, the Clean Hydrogen Partnership, which is a European Commission backed joint public-private partnership. Within the context of the Africa-Europe Green Energy Initiative, clean hydrogen opportunities are being actively considered among public and private partners through joint research and innovation projects.39

Overall, the green hydrogen sector is an important area with a potential for the African private sector to unlock commercial openings in “both the supply and demand side for energy intensive industries”.40 These innovations can be scalable through the European Green Deal Investment Plan, which wants to direct enormous resources in sustainable investments in the next decades, among others through widely adopting international carbon markets and the EU Emissions Trading System.41 Over half of the budget for the EGD will come directly from the EU budget and the EU Emissions Trading System. African countries should thus work on influencing decision-makers in the EU to increase the opportunities for the African private sector.

Supply Chain Adjustment of Critical Resources Relevant for the EU Green Deal

Europe’s transition to a green future could benefit African countries that have important critical “green” minerals in abundance. Access to resources is a strategic security question for the EU’s ambition to deliver the Green Deal. The EU aims to ensure the supply of sustainable raw materials, in particular critical raw materials necessary for clean technologies, digital, space and defense applications. A growing demand for the critical raw materials needed to establish the low carbon economy under the EGD has increased the need to strengthen sustainable supply chains, especially after the pandemic, and pressure from competitor states is compelling the EU to look for alternative sources and renewed partnerships on the African continent.42 With increasing demand from other emerging and developed countries for critical resources, diversifying supply sources from both primary and secondary sources for critical raw materials is one of the prerequisites to making this green transition happen and to establishing a functioning circular economy.

Demand for green minerals has been increasing. These minerals are the critical raw materials intended for the ‘green’ revolution, for example, nickel, cobalt, lithium, cobalt, manganese and graphite43 for batteries in electric cars, rare earth elements for permanent magnets crucial for wind turbines and electric vehicle motors44 and copper and aluminum for electricity-based technologies.45 The importance of these materials in the global “green” value chain makes it essential to ensure their “resilience and dependability” through supply chain adjustments.46

In the last two years, attempts have increased to bring production capacity close to the consumer markets by establishing trustworthy supply sources, a process called "nearshoring".47 These supply chain adjustments are opening opportunities for the African private sector, especially in East and North Africa, for more sustainable cooperation. The adjustments have to be achieved through relocating operations to the closest nations that have a “qualified workforce and reduced cost of living without the time difference”.48 For example, nearshoring activities by private companies have become more visible in countries in North Africa, particularly Morocco, due to their geographical location, infrastructural readiness, possession of abundant renewable energy resources, government support and proximity to Europe.49 African countries, such as Namibia, Malawi, Angola, Tanzania, Uganda, Madagascar, Mozambique and South Africa, have started to establish sustainable supply chains through strengthening their production and supply chain capabilities of rare earth metals.50

On the continental level, African Mining Vision emphasizes the sustainable use of critical mineral resources and the private sector’s involvement in the process.51 African countries and their private sector stakeholders are strategically important players in adjusting and de-risking the supply chain of these materials, particularly those towards EU markets: The Democratic Republic of the Congo is one of the largest producers of copper-cobalt ore,52 Namibia produces copper,53 South Africa is the largest producer of manganese and platinum,54 Zimbabwe is rich in lithium,55 Rwanda is the largest exporter of tantalum56 and Zambia has deposits such as copper, cobalt, gold and nickel.57

Opportunities of the European Green Deal for Africa’s Private Sector

Finance

To achieve the plans set out in the EGD, there are significant investment needs requiring mobilization of both the public and the private sector. There are multiple funds that assist in financing the EGD and into which African private sector stakeholders can tap, either directly or indirectly. 58

- The European Regional Development Fund59 (ERDF) finances programs where the responsibility of managing and approving the fund resources is shared between the European Commission and national and regional authorities in Member States. The fund runs from 2021-2027 and focuses on small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), digital connectivity, mobility, employment, education, skills, social inclusion, sustainable urban development, healthcare, culture, sustainable tourism and locally led development. The objective of the fund is to allow a competitive and smarter Europe to emerge while supporting a net zero carbon economy and resilient Europe.60 Public bodies, SMEs, universities, associations, NGOs and voluntary organizations can apply for funding. Foreign firms with a base in the region covered by the relevant ERDF programs can also apply, provided they meet European public procurement rules. As there is no minimum size for projects, this fund offers a good opportunity for the African private sector already active in Europe to use the ERDF to advance their own innovation and market access opportunities. This approach also allows innovative African companies to enter leading innovation centers in Europe to advance their research and development capabilities and to enter European markets.61 Through the projects, African enterprises are adding value to the continent, for example, by creating employment, fostering innovation and contributing to the region's economic competitiveness. Although the fund finances only part of a given project, participating in it creates an important leverage advantage. Having EU funding in place often encourages other partners, especially private capital, to get on board for future projects.

The European Green Deal Investment Plan (EGDIP), also discussed as the Sustainable Europe Investment Plan (SEIP) as part of the EGD, includes the Cohesion Fund.62 The Cohesion Policy legislation also comprises the regulation on the Just Transition Fund, which is part and parcel of the EGD and is a pillar of the Just Transition Mechanism (JTM). The JTM is focused on sectors that are most affected by hydrocarbon and greenhouse-gas-intensive industrial processes. Areas the JTM encompasses with a budget of 17.5 billion Euros are digital connectivity, clean energy technologies, the reduction of emissions, the regeneration of industrial sites, the reskilling of workers and technical assistance. The Just Transition Fund will be overseen under a multiannual financial framework with an additional 10 billion Euros to be funded under NextGenerationEU.63 In addition, the Cohesion Fund was set up to contribute to the overall objective of strengthening economic, social and territorial cohesion of the EU by providing financial contributions in the fields of environment and trans-European networks in the area of transport infrastructure. The EU has allocated 47.5 billion Euros from the NextGenerationEU fund and 370 billion Euros to its Cohesion Fund to pursue low-carbon economic development.64 Both funds should support activities that respect the climate and environmental standards and priorities of the Union and that ensure the transition towards a low-carbon economy in the pathway to achieving climate neutrality by 2050. Both funds are also good opportunities for the African private sector to tap into, for example, by directly working with European cities and metropolitan councils to offer sustainable solutions supporting decarbonization trends.65 - Concomitantly, Horizon Europe has become the EU’s main funding program for research and innovation and has been provided with a budget of 95.5 billion Euros. The program simplifies cooperation while bolstering the bearing of “research and innovation in developing, supporting and implementing EU policies while tackling global challenges”.66 Additionally, Horizon Europe encourages generating and improving dissemination of knowledge and technological advances. The program can provide the African private sector with opportunities to engage directly with EU institutions and to build links, with a significant portion marked for SMEs, especially for research and development purposes. However, open science principles are employed throughout the program that might deter SMEs that might want to retain their proprietary information. These principles would require a working system to allow African companies to share their information. Themes of the program for cooperation include climate, energy, mobility, digital, industry, space, health, food, bioeconomy, natural resources, agriculture and environment.67

Another program, InvestEU, has been run by the EIB Group and is modeled on the Investment Plan for Europe. The program has replaced the European Fund for Strategic Investments (EFSI) and other EU financial instruments that were offered in the 2014 – 2020 period. The InvestEU program consists of three pillars, the InvestEU Fund, the InvestEU Advisory Hub and the InvestEU Portal, with the objective of augmenting “sustainable investment, innovation, social inclusion and job creation in Europe”.68 InvestEU offers “crucial long-term funding by leveraging substantial private and public funds” with the aim of providing at least 30% of investment towards achieving the EU’s climate objectives.69 Most of the private equity and venture funds are actively interested in investing in African private ventures and always looking out for good projects.70 In doing so, these private funds rely on financing instruments created by publicly owned development banks, such as the European Investment Bank and the African Development Bank, whose joint cooperation platform is supporting high-impact and pioneering investment opportunities, mobilizing private sector financing. The Boost Africa initiative and commitment to the Desert to Power program highlight how public banks accelerate financing in priority policy areas in tandem with private investors.70

Research and innovation have been determined as areas of interest as well, providing a place for SMEs to thrive and attract investment. InvestEU is designed to make “EU funding simpler to access and more effective”, including providing guarantees from the EU budget that increase investor access to funding from commercial banks. InvestEU is slated to offer 372 billion Euros between 2021-27. 72

Other programs, such as the Global Gateway Africa – Europe Investment Package, emphasize inclusive, green and digital recovery and transformation. That package’s priority areas for cooperation with Africa are fast-tracking the green transition, digital transition, sustainable growth, employment, healthcare, education and training. The Investment Package will receive 150 billion Euros and will also assist in market integration and sector reforms along with providing the African agri-food systems sector with the environment for sustainable private investments, enabling innovation and improving nutrition. It could be a great opportunity for the private sector to expand with solutions that might be then applied within the EU and African contexts. It also allocates resources for decreasing the digital divide between Europe and Africa. It will also invest in ventures that include sub-marine and terrestrial fiber-optic cables, along with cloud and data infrastructure. Another program, The African Union – European Union Digital4Development Hub, will also assist in digital cooperation for the private sector.73 The prioritization of mobility also provides an opportunity as strategic corridors are to be constructed, with multi-country transport infrastructure to be executed.74

The African private sector could benefit from the ambitions of the 2030 Agenda, which aims at accelerating Africa’s transition to an innovation-led, scientific, knowledge-based economy value chain.75 In conjunction, the Global Green Bond Initiative has proposed that the EU will back the development and growth of green bond markets to finance sustainable and green initiatives. This support also extends to technical support. Notably, a considerable “re-channeling” of part of the EU’s Special Drawing Rights (SDR) to Africa and other vulnerable countries is envisaged through International Monetary Fund’s programs, such as the Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust and the new Resilience and Sustainability Trust Fund.76

Multiple companies from the private sector in the EU are working with African companies in the renewable sector. For instance, solar panels are being manufactured in Kenya by SOLINC, a joint venture created by the Netherlands’ Ubbink and a regional Kenyan enterprise. Similarly, the Finnish firm EkoRent Oy has been engaged in a joint venture with Infraco Africa77 to create a taxi fleet in Kenya of solar-charged electric vehicles in a scalable rideshare model called NopeaRide.78 NopeaRide has seen investment by the Energy and Environment Partnership Trust Fund (EEP Africa), which has been formed by the Austria Development Agency and the Nordic Development Fund, an institution backed by Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden.79 Together with Siemens, Volkswagen has likewise launched an e-Golf model in Rwanda as “a blueprint for electric mobility in Africa”, with similar plans in Ghana.80 The car assembly plants are seen as the first step to developing a vibrant automotive assembly sector in Africa outside South Africa.

The African Union and the EU, through the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, have recognized the importance of science, technology and innovation as a “vital driver of sustainability”. This step was reinforced by the Joint Vision for 2030 undertaken at the 6th EU-AU Summit on 17 and 18 February 2022. Additionally, the Global Gateway Africa – Europe Investment Package intends to muster up to 150 billion Euros81 in funds in the next six years for “Africa’s strong, inclusive, green and digital recovery and transformation”.82 The Green Economy Financing Facility (GEFF) is another program that has assisted SMEs by providing up to 150 million Euros in funding across the “agricultural, construction, commercial and manufacturing sectors”.83

Important financial institutions on the African continent, such as the African Development Bank and Afreximbank, are actively providing incentives to African and European private sectors to undertake sustainable investments in African countries.84 By creating innovative financial instruments such as the liquidity and sustainability facility, the banks are directly supporting the Sustainable Development Goals-related investments and green bonds on the African continent.85

Despite the growing strategic importance of African countries, however, concerns remain86 of a potential “unequal partnership” as EU priorities, exacerbated by the EGD and other policy instruments, are still dominating the development landscape.87 Especially sectors that are of great interest to the EU, such as green hydrogen or critical raw materials, could attract increased investment from Europe and at the same time create a potential lock-in effect for African countries to become yet again a mere resource supplier to the EU.88

As explained in this section, there are multiple funding opportunities, private and public, within the EU that are directly or indirectly supporting EGD goals. African private sector stakeholders can tap into these funding opportunities, although implementation procedures need to be identified on a case-by-case approach.

Technology

The EGD aims to scale commercial applications of breakthrough green technology innovations and create corresponding markets to secure an advantage over competitors in the United States and China. Due to the high costs, it could be difficult for African countries to adopt some of the emerging green technologies. However, competition between producers, especially between the EU and China, could lead to early price decreases and could enable African countries to negotiate skills, knowledge and technology transfer, and the localization of jobs around these new technologies.

Technological domain has also been highlighted in the Global Gateway Investment Package’s Innovation Agenda, where the goal is to make innovative capacities scalable, develop innovation ecosystems, enhance higher education and research and innovation partnerships, and to augment existing initiatives.89 The AU-EU Innovation and Technology partnership focuses on innovation, technology and capacity development for science.90 Funds such as TLcom Tide Africa, Partech Africa, BoostAfrica and AfricInvest Venture Capital have also been established, which have been a focal point of interest from private sector investors as the ventures work on “de-risking investment in technology”.91 The EU-AU Research and Innovation Partnership has focused on many areas, such as green transition, food and nutrition security and sustainable agriculture, climate change and sustainable energy (CCSE). The AU-EU Innovation Agenda focuses on five areas that assist in collaboration through an innovation ecosystem, innovation management, knowledge exchange, including technology transfer, access to finance and human capacity development. To achieve better collaboration, the AU-EU partnership focuses on co-creation and co-ownership, sustainability and openness. To further enhance cooperation, the EU-funded AfriConEU, the first trans-continental networking academy designed for African and European digital innovation hubs, has emerged.92

Additionally, the EU and Breakthrough Energy Catalyst are investing up to 820 million Euros from 2022 and 2027 to detect and rapidly scale projects focused on climate technology in the EU while “each euro of public funds from the partnership is expected to leverage more than twice the private funds”.93 Interestingly, “EU strategies towards Africa reveal a strong interest in large-scale mitigation and clean energy investments, whereas the EU’s programming documents for Africa focus on adaptation to the benefit of smallholder farmers”.94 This discrepancy between the overall strategy of the EU and the actual implementation approach indicates that there is no coherent approach under the EGD towards African countries. Narrowing the gap should be one of the main areas of work for decision-makers in African countries and their private sector stakeholders.

Capacity-building

According to the EGD, science and technology (S&T) dialogues between the EU and Africa “combine policy dialogue with project-based and bottom-up cooperation”.95 Egypt and the EU had also previously cooperated in the fields of research and innovation through "Shaping Egypt’s association to the European Research Area and Cooperation Action" (ShERACA+). 96

Researchers in African countries, particularly in North Africa, have received EU funding to increase participation and energy cooperation through sharing know-how on incorporating renewable energy sources into the existing energy grids and also working on upgrades in energy efficiency. The EU-funded project DISKNET has also tried to create links between scientists, including some from African countries, to advance approaches to enhancing energy distribution networks between the EU and its adjacent nations. Its research included ways to incorporate geothermal energy into energy grids, emerging “desalination plants powered by renewable energy, advancing wind and solar power, as well as investigating how to reuse waste heat from industry in an efficient way” along with other methods of carbon capture.97 The African Research Initiative for Scientific Excellence, Research and Innovation Partnership saw 44 early career researchers from 38 African countries offered up to 500,000 Euros to embark on innovative research that could support sustainable growth initiatives.98 The EU has also highlighted “Talent Partnerships” with African countries for skills development, such as Belgium’s project with Morocco, PALIM, which likewise increases links.99 Sustainability and green partnerships remain a focus of programs such as Horizon Europe, where 95.5 billion Euros are budgeted towards EU climate objectives. Under Horizon Europe, the EU will form green partnerships in various areas: batteries, clean hydrogen, low-carbon steel, the built environment and biodiversity, which can provide enormous opportunities for alignments – including with the African private sector.100

Notably, the EGD has been referred to as a cultural project exemplified by the New European Bauhaus initiative, which aims to integrate sustainability with art in achieving energy efficiency in buildings. Scholars have also highlighted the EGD dimensions that include building renovation, the circular economy and the ‘farm to fork’ strategy and retain cultural characteristics, as they provide enormous prospects for tackling climate change, influencing consumer behavior, reducing ecological footprints and nurturing social inclusion while backing a green transition.101

While the EGD and its investment plan have broad and ambitious targets, they do not yet provide details of how those targets will be realized in terms of delivery mechanisms. Through introducing new policies in sectors in which the EGD’s implications for African countries will be important, such as in agriculture, critical raw materials and new technologies,102 the EU seeks to address the twin challenges of green and digital transformations. New policies are also being introduced because the EU intends to become the frontrunner in the transition towards a green economy globally.

Therefore, an active engagement in relevant sectors offers new opportunities for the African private sector since achieving the goals set in the seven relevant areas requires strong partnerships between EU institutions, companies and stakeholders outside the EU, also with African countries and their private sector entities. For example, an EU-wide climate neutral and circular economy requires the full mobilization of the industrial sector and all the value chains involved, including those in African countries. In addition, through a planned Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), the EU is determined to ensure that decarbonization gains in the EU are not simply pushing carbon emissions outside EU borders.103 Relevant measures will mean that EU companies will need to establish a carbon neutral supply chain system, which will also affect African private sector entities as the new system will provide stronger incentives for EU and foreign industries to innovate and reduce emissions. Moreover, African companies that may already have lower carbon content in their production cycles, or in which a similar system of carbon pricing is applied, will benefit from this development under the EGD and ‘Fit for 55’ package.

The African Circular Economy Alliance identifies several major opportunities for increased circularity on the African continent: in food systems, packaging, construction, electronics, fashion and textiles.104Especially resource-intensive sectors such as textiles, construction, electronics and plastics, which are still at an early stage of development in African countries, can use opportunities under the EGD to accelerate their own low-carbon development through attracting part of the circular economy value chain from the EU towards the African private sector. For example, natural fiber resources, such as bamboo, which is abundantly available in African countries, can be used to produce sustainable construction material for the European and African construction markets.105 This approach could help strengthen local manufacturing and allow African businesses to engage in higher-value activities. The EU will step up its regulatory and non-regulatory efforts to tackle false green claims by putting demands on countries producing goods that enter EU territory.

The opportunities and challenges of the EGD for African countries when it comes to finance, technology and capacity-building are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Opportunities and challenges of EGD for African countries

| Opportunities of EGD for African countries | Challenges for African countries | |

|---|---|---|

| Finance |

Increased public and private sources of investment for African countries to tap in. New partnership development between African and European financial institutions supporting project development on the African continent, “EU funding is made simpler to access”. Use Global Gateway Africa – Europe Investment Package to advance African interest and priorities. |

The EGD and its investment plan have broad and ambitious targets but no detailed understanding in terms of financial delivery mechanisms. Sectors that are of high-interest to the EU, such as green hydrogen or critical raw materials, could attract increased investment from Europe and simultaneously create a potential lock-in effect for African countries to become yet again a mere resource supplier to the EU. |

| Technology | Use research and development parameters under EGD and Horizon Europe to advance African research and innovation capability in collaboration with African private sector entities. Competition between different producers, especially between the EU and China, could lead to early price decreases and could enable African countries to negotiate skills, knowledge and technology transfer, and help localize jobs around new green technologies. Achieving better collaboration between African countries and the EU through emphasizing partnership focused on co-creation and co-ownership of technology. |

Open science principles might deter SMEs that might want to retain their proprietary information. Requires a working system to allow African companies to share their information without losing IP. Discrepancy between the overall strategy of the EU and the actual implementation approach indicates that there is no coherent approach under the EGD towards African countries. Negotiation skills of African countries are still too weak to demand co-creation and co-ownership. |

| Capacity building | AU-EU Innovation and Technology partnership under EGD to focus on innovation, technology and capacity development for science, research and development. Increased participation of African researchers in energy cooperation with EU counterparts under “Talent Partnerships” for skills development. Under Horizon Europe, the EU will form green partnerships on various sectors: batteries, clean hydrogen, low-carbon steel, the built environment and biodiversity providing opportunities for alignments with the African private sector. The EGD as an opportunity to integrate African cultural capacity on sustainability development with enormous prospects to tackle climate change, influence consumer behavior, reduce ecological footprint, nurture social inclusion and back green transition. |

Ensuring the participation of top researchers and research institutions across Africa. Keeping a fair geographical and cultural representation. Potential divide between North African and Sub-Saharan African countries in implementing the EGD with European countries. |

Modalities for Accessing the European Green Deal in Africa

Direct access

The transition to sustainable and green technology has provided opportunities for cooperation between European and African private sector actors.106 Companies across the world can apply directly to funds such as Horizon Europe, which advances direct access to the EGD. Other opportunities include the Africa Energy Guarantee Facility (AEGF), launched by the European Investment Bank as a risk mitigation instrument focusing on sustainable energy projects in Africa.107 Another opportunity is the EDFI AgriFI,108 a 120 million Euro impact investment facility funded by the EU with a mandate to provide medium- to long-term financing to private sector enterprises active in the agri-food value chain, with a focus on smallholder farmers.

In the last years, European and international financial institutions have partnered under different networks according to their scope of intervention, strategic priorities, interests and needs. These establishments are:

- The ‘Interact Climate Change Facility’ (ICCF), shareholders of ICCF currently include: AFD, EIB, CDC, DEG, PROPARCO, BIO, Finnfund, COFIDES, Norfund, OeEB, SIFEM and Swedfund.

- The ‘European Financing Partners’, shareholders are EIB and 13 EU DFIs: BIO, CDC, COFIDES, DEG, Finnfund, FMO, IFU, PROPARCO, Norfund, SBI-BMI, Swedfund, SIFEM and OeEB.

- The Friendship Facility includes PROPARCO - France, FMO - the Netherlands and DEG - Germany.109

- Germany’s Invest for Employment program has also opened funding opportunities for the African private sector from eight African countries, with an emphasis on sustainability and job creation supporting projects.110

New EU-based funds, such as Mirova’s Sunfunder Gigaton Clean Energy SME Fund, have established financing instruments targeting SMEs active in generating and providing clean energy in emerging markets, with a particular focus on Sub-Saharan Africa.111

Space technology can also play a positive role in supporting sustainability. The private sector is a partner in a multitude of space research projects supported by Framework Programme for Research and Technological Development (FP7) and the H2020 space program on space research.112

With European Partners

The Circular Biobased Europe public-private partnership is focused on bio-based solutions. Processes4Planet is also a public-private partnership aimed at resource efficient and flexible CO2 capture and utilization.113

As a European Subsidiary

Atlantica Ventures has become the African investment partner to benefit from the Boost Africa initiative.114 Atlantica Ventures has been pitched as “an early-stage pan-African impact focused venture capital fund, with the belief that Africa’s and the world’s problems can and will be solved by African entrepreneurs channeling their passion and skills through technology”. Its aim is to have sustainable and scalable business models that would increase the formal sector workforce while increasing financial inclusion. The venture is being provided capital from Boost Africa and 11 million Euros in capital from the European Investment Bank.115 Equally, Africa-based Venture Capital companies, such as Inspired Evolution,116 have set up dedicated funds targeting clean energy development on the African continent, areas targeted by the EGD.

The modalities for accessing the EGD are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2: Modalities for Accessing the European Green Deal in Africa

| Direct Access | |

|---|---|

| Africa Energy Guarantee Facility | |

| EDFI AgriFI | |

| Interact Climate Change Facility | |

| European Financing Partners | |

| The Friendship Facility | |

| With European Partners | |

| Circular Biobased Europe | |

| Processes4Planet | |

| The European Regional Development Fund | |

| Cohesion Fund | |

| As a European Subsidiary | |

| Atlantica Venture Capital Fund | |

| Inspired Evolution III Fund | |

| ABI- West Africa Risk Sharing Facility |

Recommendations to the African Private Sector on how to Benefit from The European Green Deal

The EGD has opened new opportunities for the African private sector to become an active player in a low-carbon economy development within the EU and in African countries. There are increased opportunities for financial access, technology transfer and capacity building under the EGD and an increasing number of European institutions are looking for opportunities on the African continent. However, African countries and their private sectors must take proactive steps to tap into the financial, technological and capacity development opportunities offered through the EGD. The all-encompassing nature of the EGD and subsequent regulations will impact the African private sector, for example, through export of products into the EU markets or how and when capacity building co-operations are designed and implemented. Therefore, the African private sector should allocate time and resources to identifying sectors and programs that can be actively used for its own development.

- Active policy support by African governments could create a conducive environment for the African private sector to identify more opportunities under the EGD. For instance, targeted match-making events between EU-based companies working on the different EGD subprograms and the African private sector could allow for the build-up of more cooperation possibilities.

- African private sector associations should actively seize the opportunities emerging from the EU’s drive towards establishing sustainable supply chains, especially for critical mineral resources. A strong working relationship between African and EU private sector associations could help establish a pathway for more cooperation and knowledge sharing mechanisms. The more the African private sector is informed about EU’s sustainable supply chain legislation, the better it can prepare to become a partner for EU companies.

- African governments and private sector associations should look for a structured dialogue on how African companies can access the many funds deployed under the EGD. Currently, single private sector actors are using opportunities based on their own initiatives. This dialogue could be organized in a structured way to help more African companies access these funds.

- The EGD might also have negative repercussions for African countries if not dealt with carefully. For example, the different hydrogen relationships between Europe and Africa could reinforce long-term dependencies and lock-in effects for African countries, affecting their development trajectory. These difficulties should be avoided through advance planning and participation of African private sector players from the start of anticipated projects. It is also critical that political decision-makers are well informed before rushing into accepting projects that could have negative consequences for the African private sector development.

- The EGD may increase import regulations affecting African private sector export into the EU markets, especially for agricultural products.117 This increase might even create tensions with trading partners as the EU might put tariffs on carbon-intensive imports118 and a carbon border adjustment mechanism might be perceived as an unlawful trade barrier.119 However, as environmental and sustainability standards are slated to become stricter for the African private sector due to the EGD, it is imperative to implement in-house standards so as not to be subject to supply chain and market disruption owing to changing EU standards.

Especially the agriculture sector will see more investment120 as incubators such as Ocean Hub Africa, Itanna, FbStart Accelerator, ARM Labs Innovation and Flat6Labs are becoming instrumental in establishing private sector capacity in Africa, especially at a time when the EGD is bringing forth various sectors that welcome cooperation. Already established sectors also have prospects that are currently not scalable, such as in remanufacturing and recycling facilities. However, some challenges must be overcome, for example, a rising informal sector, a “missing middle” in the size of enterprises, environmental degradation and unsustainable practices, impeded mobility, limited infrastructure facilities, lack of export competitiveness and complexity in registering business and taxation.121

Conclusion

The European Green Deal is the next wave of economic development, and African stakeholders need to be engaged and to put their own development ideas into shaping the low-carbon economy on the African continent as well as elsewhere. The EGD could provide opportunities for the African private sector to offer answers for problems that require scalable solutions and allow the transition to a low carbon economy. The EGD has also been designed with cooperation in mind, which can be leveraged by the private sector. One of the major concerns connected to the EGD has been the divergence between EU priorities and the continental, regional and local priorities in Africa, which make it challenging for the African private sector to fully use the EGD opportunities. In addition, the EGD’s concrete implementation procedures are not yet clear and might undergo many changes and adjustments in the coming years. However, there are prospects for greater collaboration in technology expansion and transfer and for boosted financing in sunrise sectors, skill development, knowledge sharing and sustainable finance.

Due to their proximity to the European continent, particularly countries and companies in North Africa are slated to be provided with relatively more focus and attention as nearshoring and reshoring activities of European companies offer opportunities for the African private sector to play a bigger role in supply chain management. In addition, the EU’s multiple financing opportunities, technology transfer and capacity building programs offer a broad framework for the African private sector to tap into. However, the African private sector can only benefit from these opportunities through the active participation of African decision-makers in influencing the concrete implementation procedures of EGD programs. By strategically positioning the African private sector, a more useful interaction and framework could be generated.

- "A “Green Deal” for Africa to recover from the crisis and “reduce inequalities”." 2021portugal.eu. Last modified April 23, 2021. https://www.2021portugal.eu/en/news/a-green-deal-for-africa-to-recover-from-the-crisis-and-reduce-inequalities.

- Rama Yade, “The Ukraine war is giving Europe a chance to reset ties with Africa”, The Atlantic Council, 16 June 2022: https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/africasource/the-ukraine-war-is-giving-europe-a-chance-to-reset-ties-with-africa/, accessed on 15 August 2022.

- Morocco and EU sign deal to boost cooperation on renewable energy." Africa News, October 19, 2022. https://www.africanews.com/2022/10/19/morocco-and-eu-sign-deal-to-boost-cooperation-on-renewable-energy/

- “European Green Hydrogen Accelerator Centre”: https://eghac.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/eit-innoenergy-announces-new-initiative-to-speed-climate-neutrality-by-developing-100-billion-a-year-green-hydrogen-econo.pdf , accessed on 28 August 2022.

- van Wijk, Ad, Kirsten Westphal, and Jan F. Braun. How to deliver on the EU Hydrogen Accelerator. May 2022. http://files.h2-global.de/H2Global_How-to-deliver-on-the-EU-Hydrogen-Accelerator.pdf.

- "Global Gateway." European Commission. Accessed December 12, 2022. https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/stronger-europe-world/global-gateway_en.

- Tanchum, Michaël. "Gateway to growth: How the European Green Deal can strengthen Africa’s and Europe’s economies." European Council on Foreign Relations, January 19, 2022. https://ecfr.eu/publication/gateway-to-growth-how-the-european-green-deal-can-strengthen-africas-and-europes-economies/#summary

- Islam, Shada. "Decolonising EU-Africa Relations Is A Pre-Condition For A True Partnership Of Equals." Center for Global Development, February 15, 2022. https://www.cgdev.org/blog/decolonising-eu-africa-relations-pre-condition-true-partnership-equals.

- “Has the EU missed the boat on Africa?”, Deutsche Welle, https://www.dw.com/en/opinion-has-the-eu-missed-the-boat-on-africa/a-60834930, accessed 24 November 2022.

- Ünveren, Burak. "Turkey: Africa's 'anti-colonial benevolent brother'." DW, April 2, 2022. https://www.dw.com/en/turkey-seeks-to-strengthen-africa-relations-with-benevolence/a-56452857

- "China and Africa: Strengthening Friendship, Solidarity and Cooperation for a New Era of Common Development." Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People's Republic of China, August 19, 2022. https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/eng/zxxx_662805/202208/t20220819_10745617.html.

- "India Seeks to Strengthen its Longstanding Ties with Africa." International Institute for Sustainable Development, September 25, 2022. https://www.iisd.org/articles/news/india-strengthen-ties-africa.

- Brazil Africa Forum 2022. Accessed December 12, 2022. https://forumbrazilafrica.com/.

- Eurostats: “EU imports of energy products- recent developments”: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=EU_imports_of_energy_products_-_recent_developments#Main_suppliers_of_natural_gas_and_petroleum_oils_to_the_EU, accessed 14 September 2022.

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Research and Innovation, 2021. Horizon Europe boosts EU-Africa cooperation in research & innovation, Publications Office. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2777/1333

- "EU-Africa cooperation through Erasmus+ ." European Commission. Accessed December 12, 2022. https://ec.europa.eu/assets/eac/erasmus-plus/factsheets/regional/erasmusplus-regional-africa2017.pdf.

- “Africa-EU Partnership”, European Commission, URL: https://international-partnerships.ec.europa.eu/policies/africa-eu-partnership_en, accessed on 21 August 2022.

- "Africa-EU Partnership." European Commission. Accessed December 12, 2022. https://international-partnerships.ec.europa.eu/policies/africa-eu-partnership_en.

- "DOCUMENTS African Union Green Recovery Action Plan 2021-2027." African Union. Last modified July 15, 2021. https://au.int/en/documents/20210715/african-union-green-recovery-action-plan-2021-2027.

- Siemens Gamesa: “Unlocking European Energy Security”, https://www.siemensgamesa.com/en-int/products-and-services/hybrid-and-storage/green-hydrogen/unlocking-european-energy-security, accessed 24 November 2022.

- „Geopolitics of the Energy Transformation: The Hydrogen Factor, IRENA, https://www.irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Publication/2022/Jan/IRENA_Geopolitics_Hydrogen_2022.pdf?rev=1cfe49eee979409686f101ce24ffd71a, accessed 24 November 2022.

- “Geopolitics of the energy transition: the hydrogen factor”, IRENA 2022: https://irena.org/publications/2022/Jan/Geopolitics-of-the-Energy-Transformation-Hydrogen/digitalreport , accessed 2 September 2022.

- “African Green Hydrogen Alliance launches with eyes on becoming a clean energy leader”: https://climatechampions.unfccc.int/african-green-hydrogen-alliance-launches-with-eyes-on-becoming-a-clean-energy-leader/, accessed 25 August 2022.

- Kieran Whyte, “South Africa's Green Hydrogen Policy”, 26 November 2021, Baker McKenzie: https://www.bakermckenzie.com/en/insight/publications/2021/11/south-africa-green-hydrogen-policy, accessed on 22 August 2022.

- Hafid Boutelab, “Morocco to Ramp Up Green Hydrogen Production”, Al Monitor, 23 May 2022: https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2022/05/morocco-ramp-green-hydrogen-production#:~:text=In%202019%2C%20the%20Moroccan%20Ministry,half%20of%20the%20kingdom's%20already, accessed on 18 August 2022.

- Byjoel K. Bourne, Jr., “Global food crisis looms as fertilizer supplies dwindle”, National Geographic, 23 May 2022: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/article/global-food-crisis-looms-as-fertilizer-supplies-dwindle, accessed on 18 August 2022.

- “Morocco forms the first green hydrogen production system”, https://energynews.biz/morocco-forms-the-first-green-hydrogen-production-system/, accessed 17 September 2022.

- “Geopolitics of the Energy Transformation The Hydrogen Factor”, International Renewable Energy Agency, January 202: https://www.irena.org/publications/2022/Jan/Geopolitics-of-the-Energy-Transformation-Hydrogen, accessed on 17 August 2022.

- “Hyphen Energy: Shareholder” https://hyphenafrica.com/shareholders/, accessed 4 September 2022.

- Nikolaus J. Kurmayer, “EU aims to make Africa a world champion in hydrogen exports”, Euractiv, 15 February 2022: https://www.euractiv.com/section/energy/news/eu-aims-to-make-africa-a-world-champion-in-hydrogen-exports/, accessed on 21 August 2022.

- van den Berg, Johan. "POLICY BRIEF 2020/01: Green Hydrogen – Fuelling human well-being in Africa and Europe." Africa-EU Energy Partnership (February 29, 2020).

- https://doi.org/https://africa-eu-energy-partnership.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/AEEP-Green-Hydrogen-Policy-Brief-Publication-version-Final.pdf.; Zainab Usman, Olumide Abimbola, and Imeh Ituen: “What does the European Green Deal Mean for Africa”, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace 2021: https://carnegieendowment.org/files/202110-Usman_etal_EGD_Africa_final.pdf, accessed 03 September 2022.

- Ad van Wijk and Frank Wouters, “Hydrogen–The Bridge Between Africa and Europe”, in: Margot P. C. Weijnen, Zofia Lukszo, Samira Farahani (eds), Shaping an Inclusive Energy Transition, (Springer: Berlin, 2021).

- “Speech Executive Vice-President Frans Timmermans at the World Hydrogen Summit”, European Commission, 10 May 2022,

"Speech Executive Vice-President Frans Timmermans at the World Hydrogen Summit." European Commission. Last modified May 10, 2022. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/SPEECH_22_2981.accessed on 22 August 2022. - Victoria Masterson, “How Africa could become a Global Hydrogen Powerhouse”, World Economic Forum, 21 July 2022: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/07/africa-hydrogen-iea/hydrogen, accessed on 21 August 2022.

- “How ports can be transformed into energy hubs of the future” 29 April 2022, How ports can be transformed into energy hubs of the future | World Economic Forum (weforum.org).

- “A Hydrogen Strategy for a climate-neutral Europe”, European Commission 2020, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0301 , accessed 02 September 2022.

- “Delivering The Green Deal: The Role of Clean Gases Including Hydrogen,” European Commission, 15 December 202: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/api/files/attachment/870606/Factsheet%20Hydrogen%20Gas_EN.pdf.pdf, accessed on 15 August 2022.

- “Hydrogen Energy Network meetings”: https://energy.ec.europa.eu/topics/energy-systems-integration/hydrogen/hydrogen-energy-network-meetings_en , accessed 02 September 2022.

- Africa - EU Green Energy Initiative." European Commission. https://europa.eu/capacity4dev/tei-jp-tracker/tei/africa-eu-green-energy-initiative.

- "EU-Africa: Global Gateway Investment Package." European Commission. Accessed December 12, 2022. https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/stronger-europe-world/global-gateway/eu-africa-global-gateway-investment-package_en.

- "The EU Green Deal explained." Norton Rose Fullbright. Last modified April , 2021. https://www.nortonrosefulbright.com/de-de/wissen/publications/c50c4cd9/the-eu-green-deal-explained#:~:text=Funding%20the%20EU%20Green%20Deal,-The%20proposed%20financing&text=Over%20half%20of%20the%20b.

- Vladimir Shopov, “The Inevitable Partner: Why Europe Needs To Re-Engage With Africa”, European Council on Foreign Relations, 30 July 2020,: https://ecfr.eu/article/commentary_the_inevitable_partner_why_europe_needs_to_re_engage_with_africa/#:~:text=Africa%20is%20the%20European%20Union's,significant%20impact%20on%20Europe's%20future, accessed on 21 August 2022.

- Nicholas Norbrook, “Can Africa leverage Europe’s Green New Deal?”, The Africa Report 29 October 2021, URL: https://www.theafricareport.com/141274/can-africa-leverage-europes-green-new-deal/, accessed on 22 August 2022.

- “Critical materials for the energy transition: rare earth elements”, IRENA, https://www.irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Technical-Papers/IRENA_Rare_Earth_Elements_2022.pdf, accessed 28 August 2022.

- “The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions”, International Energy Agency, URL: https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/ffd2a83b-8c30-4e9d-980a-52b6d9a86fdc/TheRoleofCriticalMineralsinCleanEnergyTransitions.pdf, accessed on 23 August 2022.

- Rebeca Grynspan, “Here's how we can resolve the Global Supply Chain Crisis”, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, 18 January 2022 URL: https://unctad.org/news/blog-heres-how-we-can-resolve-global-supply-chain-crisis, accessed on 22 August 2022.

- Tarek Sultan, “5 ways the COVID-19 pandemic has changed the supply chain”, World Economic Forum, 14 January 2022, URL: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/01/5-ways-the-covid-19-pandemic-has-changed-the-supply-chain/, accessed on 22 August 2022.

- Maritza Diaz, “Beyond Outsourcing: How To Get Started With Nearshoring”, Forbes, 27 May 2021, URL: https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbestechcouncil/2021/05/27/beyond-outsourcing-how-to-get-started-with-nearshoring/?sh=4b6a88701799 , accessed on 22 August 2022.

- “Why German Corporations are Nearshoring in Morocco”, The Maritime Executive, 21 August 2022, https://maritime-executive.com/article/why-german-corporations-are-nearshoring-in-morocco

- Pier Paolo Raimondi, “The Scramble for Africa’s Rare Earths: China is not Alone”, Italian Institute for International Political Studies, 7 June 2021, URL: https://www.ispionline.it/en/publication/scramble-africas-rare-earths-china-not-alone-30725, accessed on 18 August 2022.

- About AMV." Africa Mining Vision. Accessed December 12, 2022. https://www.africaminingvision.org/about.html.

- “Renewable Energy Market Analysis: Africa and Its Regions”, International Renewable Energy Agency and African Development Bank, 2022, URL: https://www.irena.org/publications/2022/Jan/Renewable-Energy-Market-Analysis-Africa, accessed on 22 August 2022.

- Alec Crawford, Jessica Mooney and Harmony Musiyarira, “ IGF Mining Policy Framework Assessment”, International Institute for Sustainable Development, 2018, URL: http://www.jstor.com/stable/resrep21962.5, accessed on 22 August 2022.

- Pistilli, Melissa, and Georgia Williams. "Top 5 Palladium- and Platinum-producing Countries (Updated 2022)." Investing News, November 7, 2022. https://investingnews.com/daily/resource-investing/precious-metals-investing/

platinum-investing/top-platinum-palladium-producing-countries/. Pistilli, Melissa. "Top 10 Manganese-producing Countries (Updated 2022)." Investing News, September 21, 2022. https://investingnews.com/daily/resource-investing/battery-metals-investing/manganese-investing/top-manganese-producing-countries/. - Alexandria Williams, “China Beats Competition to Secure Zimbabwe Lithium”, DW, 11 July 2022, URL: https://p.dw.com/p/4Dwjp, accessed on 23 August 2022.

- Pistilli, Melissa. "Top 5 Tantalum-mining Countries (Updated 2022)." Investing News, March 16, 2022. https://investingnews.com/daily/resource-investing/critical-metals-investing/tantalum-investing/2013-top-tantalum-producers-rwanda-brazil-drc-canada/.

- Database of Mineral Resources of Zambia. Warsaw: International Workshop on UNFC, 2010. https://unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/energy/se/pp/unfc/UNFC_iw_June10_WarsawPl/14_Nyambe_Phiri.pdf.

- Sources of finance to fund the EGD are estimated as follows: The EU budget will contribute €503 billion (from 2021 to 2030) of spending on the environment across all EU programmes while national government co-financing contributions, alongside EU structural funds, are expected to amount to €114 billion. Invest EU will mobilize €279 billion (from 2021 to 2030) of private and public climate-related investments by, inter alia, offering guarantees to reduce the risk in operations. EU Emissions Trading Scheme revenues from carbon allowances allocated will contribute an estimated €25 billion.

- “Regulation (EU) 2021/1058 of the European Parliament and of the council of 24 June 2021 on the European Regional Development Fund and on the Cohesion Fund”, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32021R1058 , accessed on 5 September 2022.

- “Regulation (EU) 2021/1058 of the European Parliament and of the council of 24 June 2021 on the European Regional Development Fund and on the Cohesion Fund”, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32021R1058 , accessed on 5 September 2022.

- “European Regional Development Fund”, European Commission, 30 June 2020, URL: https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/funding/erdf, accessed on 17 August 2022.

- “African Bamboo selects Delft for their applied R&D center” https://www.innovationquarter.nl/en/african-bamboo-selects-delft-for-their-applied-rd-center/, accessed 28 October 2022.

- EU funding is channeled through the five European Structural and Investment Funds (ESIF) jointly managed by the European Commission and the EU countries. The ESFI comprises five funds: the European social fund (ESF), the Cohesion Fund (CF), the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD) and the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund (EMFF).

- “Just Transition Fund”, European Commission, URL: https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal/finance-and-green-deal/just-transition-mechanism/just-transition-funding-sources_en, accessed on 17 August 2022.

- "2021-2027 Cohesion Policy overview." European Commission. https://cohesiondata.ec.europa.eu/cohesion_overview/21-27#.

- "Horizon Europe." European Commission. Accessed December 12, 2022. https://research-and-innovation.ec.europa.eu/funding/funding-opportunities/funding-programmes-and-open-calls/horizon-europe_en.

- “Horizon Europe”, European Commission, URL: https://ec.europa.eu/info/research-and-innovation/funding/funding-opportunities/funding-programmes-and-open-calls/horizon-europe_en, accessed on 17 August 2022.

- “About InvestEU”, European Commission, URL: https://investeu.europa.eu/about-investeu_en, accessed on 17 August 2022.

- "InvestEU: European Commission and Council of Europe Development Bank sign agreement to mobilize €500 million in financing for social investments." European Commission. Last modified November 28, 2022. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/%20en/ip_22_7165.

- Among the leading investors are IFC, the private-sector investment arm of the World Bank, UK’s CDC, Proparco of France and DEG of Germany. Companies such as African Infrastructure Investment Managers (AIIM), Africinvest, Adenina, Amethis, ECP, Old Mutual and Helios have also invested in African ventures. In 2021 a total of US$ 7bn were committed by private sector investors. Areas of investment include sustainable transport; energy efficiency, digital and transport system, digital connectivity, supply and processing of raw materials, space, waste management that prioritizes the circular economy, health and long-term care, cultural heritage, tourism and innovative technologies to tackle climate change. https://thecapitalquest.com/2022/01/14/meet-the-most-active-private-equity-investors-in-africa/

- “AfDB-EIB Indicative Joint Action Plan for 2020-22”, https://www.afdb.org/sites/default/files/2021/01/20/eib_afdb_joint_action_plan_2020-2022_final_19.01.2021.pdf, accessed 2 November 2022.

- “InvestEU Programme”, Vlaanderen.be (Flemish government), URL: https://eufundingoverview.be/funding/investeu-programme, accessed on 22 August 2022.

- “The Digital for Development Hub”, https://d4dhub.eu/, accessed 10 November 2022.

- “EU-Africa: Global Gateway Investment Package”, European Commission, URL: https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/stronger-europe-world/global-gateway/eu-africa-global-gateway-investment-package_en, accessed on 22 August 2022.

- "Strategic Vision for Africa 2030." UNODC. Accessed December 12, 2022. https://www.unodc.org/documents/Advocacy-Section/UNODC_Strategic_Vision_for_Africa_2030-web.pdf.

- “EU-Africa: Global Gateway Investment Package”, European Commission, URL: https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/stronger-europe-world/global-gateway/eu-africa-global-gateway-investment-package_en, accessed on 16 August 2022.

- InfraCo Africa’s involvement will enable the company to grow its NopeaRide Electric Vehicles fleet up to 100 (70 additional), in tandem with the expansion of the required charging infrastructure across the city. New charging stations will be rolled out in an efficient and cost-effective manner using data derived from Nopea applications (both drivers and passengers), Nopea vehicles, charging stations, and by monitoring traffic flow and popular journey routes. NopeaRide now has 14 grid-tied charging points in six locations across Nairobi and recently began development of the city’s first solar charging hub. ("Kenya: EkoRent Nopea." InfraCo Africa. Accessed December 12, 2022. https://infracoafrica.com/project/ekorent-nopea/.)

- Michaël Tanchum, “Europe’s Winning Formula For Spending €150 billion in Africa”, Efficacité et Transparence des Acteurs Européens, 15 February 2022, URL: https://www.euractiv.com/section/africa/opinion/europes-winning-formula-for-spending-e150-billion-in-africa/, accessed on 19 August 2022.

- Michaël Tanchum, “Gateway to growth: How the European Green Deal can strengthen Africa’s and Europe’s economies”, European Council on Foreign Relations, 19 January 2022, URL: https://ecfr.eu/publication/gateway-to-growth-how-the-european-green-deal-can-strengthen-africas-and-europes-economies/, accessed on 21 August 2022.

- Michaël Tanchum, “Europe’s Winning Formula For Spending €150 billion in Africa”, Efficacité et Transparence des Acteurs Européens, 15 February 2022, URL: https://www.euractiv.com/section/africa/opinion/europes-winning-formula-for-spending-e150-billion-in-africa/, accessed on 19 August 2022.

- “EU reveals €150 billion investment plan for Africa”. https://www.dw.com/en/eu-reveals-150-billion-investment-plan-for-africa/a-60731816, accessed 27 October 2022.

- “Supporting Africa’s Science And Innovation: 44 African Scientists Awarded EU Funded ARISE Grants of up to €500 000”, European Commission, 16 June 2022, URL: https://international-partnerships.ec.europa.eu/news-and-events/news/supporting-africas-science-and-innovation-44-african-scientists-awarded-eu-funded-arise-grants-eu500-2022-06-16_en, accessed on 19 August 2022.

- “EU Offers €4m To Support Egypt’s Environmental Efforts, Green Industry”, Daily News Egypt, 8 August 2022, URL: https://dailynewsegypt.com/2022/08/08/eu-offers-e4m-to-support-egypts-environmental-efforts-green-industry/, accessed on 22 August 2022.

- Vera Songwe, “Africa and Europe: A time for Action”, United Nations Africa Renewal, 16 February 2022. URL: https://www.un.org/africarenewal/magazine/february-2022/africa-and-europe-time-action, accessed on 24 August 2022.

- Escoffier, David. "The Liquidity and Sustainability Facility (LSF) closes inaugural $100 million repo transaction at COP27 with Afreximbank and Citi to improve the liquidity of African sovereign bonds, relying on innova." Afreximbank (November 14, 2022).

- https://www.afreximbank.com/the-liquidity-and-sustainability-facility-lsf-closes-inaugural-100-million-repo-transaction-at-cop27-with-afreximbank-and-citi-to-improve-the-liquidity-of-african-sovereign-bonds-relying-on-innova/

- Niall Duggan and Luis Mah and Toni Haastrup, “Africa’s Relations with the EU: a Reset Is Possible If Europe Changes Its Attitude”, The Conversation, 17 February 2022, URL: https://theconversation.com/africas-relations-with-the-eu-a-reset-is-possible-if-europe-changes-its-attitude-177250, accessed on 23 August 2022

- Veit Bachmann, “The EU as a Geopolitical and Development Actor: Views from East Africa”, 2013, URL: https://doi.org/10.4000/espacepolitique.2561, accessed on 22 August 2022.

- “Hydrogen from North Africa- a neocolonial resource grab”, https://corporateeurope.org/en/2022/05/hydrogen-north-africa-neocolonial-resource-grab, accessed 7 November 2022.

- “New EU-AU Innovation Agenda to drive sustainable growth and jobs”, European Commission, 18 February 2022, URL: https://ec.europa.eu/info/news/new-eu-au-innovation-agenda-drive-sustainable-growth-and-jobs-2022-feb-18_en, accessed on 21 August 2022.

- “The AU-EU Innovation Agenda”, European Commission, 14 February 2022, URL: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/research_and_innovation/events/documents/final_au-eu_ia_14_february.pdf, accessed on 22 August 2022.

- “A Partnership with Africa European Investment Bank 2021”, European Investment Bank, 2021, URL: https://www.eib.org/attachments/country/a_partnership_with_africa_en.pdf#:~:text=The%20European%20Investment%20Bank%20is%20the%20only%20financial,billion%20in%20concrete%20projects%20signed%20in%202020%20alone%29, accessed on 21 August 2022.

- “The first Trans-continental Networking Academy for African and European Digital Innovation Hubs” https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/101016687, accessed 7 November 2022.

- Ann Mettler, “Europe’s Ambitious Climate Goals call for a New Generation of Public-Private Partnerships”, Breakthrough Energy, 11 January 2022, URL: https://www.breakthroughenergy.org/articles/a-new-generation-of-public-private-partnerships, accessed on 21 August 2022.

- "Supporting adaptation in African agriculture – A policy shift since the EU Green Deal?." The European Business Council for Africa. Last modified June 30, 2022. https://www.ebcam.eu/publications/reference-reports-and-documents/3043-supporting-adaptation-in-african-agriculture-a-policy-shift-since-the-eu-green-deal.

- “International cooperation”, European Commission, URL: https://research-and-innovation.ec.europa.eu/strategy/strategy-2020-2024/europe-world/international-cooperation_en#Horizon-Europe, accessed on 20 August 2022.