Summary

- Methane has over 80 times the warming potency of CO2 over a twenty-year span, with a significant negative impact on climate change, the environment, air quality, and human health.

- As Africa's leading oil and gas producer, Nigeria faces challenges with methane emissions, underscoring the need for mitigation and reduction measures in support of its climate goals and social and economic objectives.

- Nigeria's leadership role as a Global Methane Pledge Champion, emphasizes its commitment to address methane emissions, especially in the oil and gas sectors.

- Additionally, COP28 showcased global commitment to methane emission mitigation and reduction in the form of USD 1 billion in funding, new transformative partnerships, and major oil and gas companies’ pledge of near-zero methane emissions by 2030.

- Bridging technical, economic, regulatory, and social gaps, as well as the alignment of methane mitigation and reduction efforts with broader transformative development objectives is essential for effective and sustainable action.

Background and Introduction

The recent COP28 conference in Dubai witnessed significant strides towards the global commitment to methane emission reduction. Notably, international stakeholders announced groundbreaking developments, including over USD 1 billion in new funding grants by the Global Methane Pledge (GMP) partners1 for methane action mobilized since COP27. Furthermore, a transformative partnership emerged among national and subnational governments, accompanied by decisive actions on waste, food, and agriculture, which are also major sources of methane in Africa.2 The expanded leadership, with countries like Bolivia, Brazil, Canada, Federated States of Micronesia, Germany, South Korea, Spain, Japan, and Nigeria joining as Global Methane Pledge Champions alongside the United States and the European Union, represents a crucial step towards unified global efforts. Equally noteworthy is the recognition, beyond mere rhetoric, of the necessity for transformational data tools. This includes the full launch of the Methane Alert and Response System (MARS)3 and the initiation of the new Data for Methane Action Campaign. Additionally, a momentous pledge from top oil and gas companies, with fifty major players committing to near-zero methane emissions and an end to routine gas flaring in their operations by 2030, underscores a significant industry-wide shift toward sustainability and environmental responsibility.4

Nigeria´s commitment to climate action, and more specifically to methane reduction and mitigation, was highlighted by President Bola Ahmed Tinubu. Sharing a platform with the COP28 President Dr. Sultan Ahmed al-Jabar, the United States Special Envoy on Climate, John Kerry, and the Chinese Envoy on Climate, Xie Zhenhue, President Tinubu reiterated his administration’s commitment to ending gas-flaring in line with the global push to halt methane emissions.

This framing paper presents an overview of the context, status, and trends of methane mitigation and reduction in Nigeria's oil and gas sectors. It outlines how the topic is understood in terms of narratives and perceptions as well as how it is acted upon at the national, subnational, and societal levels. The paper concludes by showing how addressing the methane pollution challenge can be leveraged and integrated into broader climate changeand sustainabledevelopment goals to generate broader environmental, health, and societal impacts in Nigeria.

The Value and Importance of Methane Mitigation and Reduction

The imperative to address methane emissions stems from a well-established scientific consensus on their detrimental impact on Earth's climate and human well-being5. Indeed, methane, with over 80 times the warming potency of carbon dioxide over a twenty-year span, significantly contributes to global warming, necessitating accelerated reductions to meeting the 2030 1.5°C or 2°C temperature targets set by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)6. In response, COP26 saw the launch of the Global Methane Pledge (GMP).7 Urged on by the global community, the GMP took advantage of COP28 to invite more members, such that Nigeria is now part of the leadership panel as a Global Methane Pledge Champion. The GMP has continued to advance the course of investing in methane emission reduction as a pivotal strategy in the fight against climate change, presenting sustainable benefits for future and current generations.

According to UNEP, evidence reveals how methane is implicated – beyond its role in climate change – in the formation of ground-level ozone, a hazardous air pollutant linked to a staggering one million deaths annually and the loss of up to 110 million tonnes of crops.8 Hence, mitigating methane emissions not only addresses climate change, but also delivers a dual benefit by enhancing air quality and human health. This aligns seamlessly with Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)9 12, 13, 14, and 15, focused on fostering cleaner environments, resilient ecosystems, and overall societal well-being while advancing key global objectives like affordable and clean energy (SDG-7), industry innovation (SDG-9), and sustainable communities (SDG-11).

The Status and Trends of Methane Emissions in Nigeria

As Africa's leading oil and gas producer, in 2010 Nigeria recorded an estimated 439.8 kilotonnes of methane emissions within the Oil and Gas sector10. These emissions encompassed diverse activities such as gasoline distribution and handling, oil production, oil refining, oil transport, as well as gas production, processing, and distribution11. Notably, 27% of these emissions were associated with oil production, while a significant majority, 73%, emanated from gas production, processing, and distribution. The projected trajectory indicates a rise in methane emissions to 481.2 kilotonnes in 2030, a 9% increase. The peak is anticipated in 2050, reaching 598.5 kilotonnes, a substantial 36% rise12. Notably, gas production and processing stood out as the primary source of methane emissions within the Oil and Gas sector13.

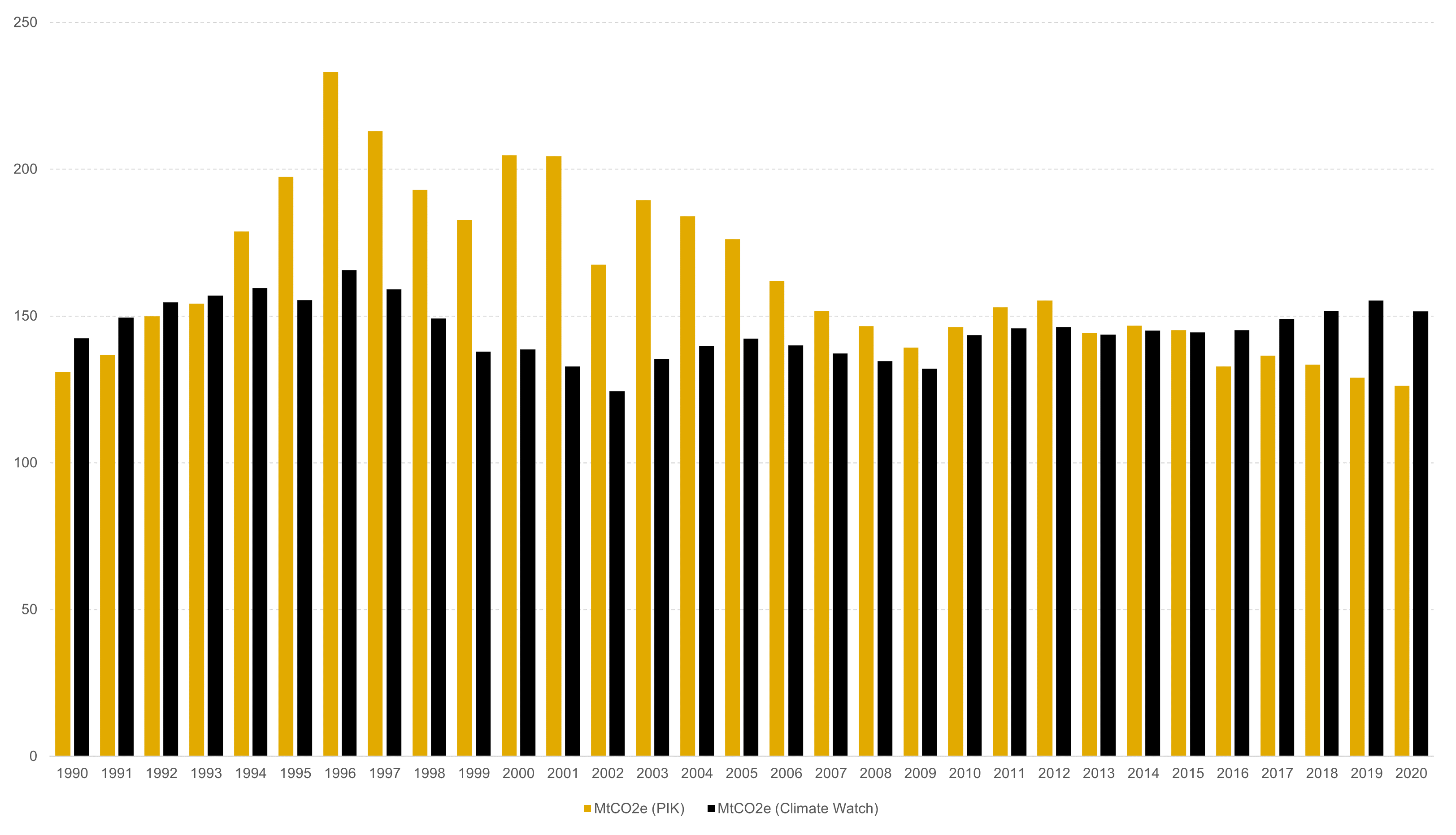

Climate Watch Data also supports these findings, showing that methane emissions from the oil and gas sectors in Nigeria have been increasing steadily since 2010. In 2020, methane emissions from the sector reached 152.95 million metric tons of CO2 equivalent, MtCO2e (see Figure 1). This is equivalent to about 41% of Nigeria's total greenhouse gas emissions14. This increase is due to several factors, including the expansion of oil and gas production in Nigeria, leaks from oil and gas pipelines and infrastructure, and venting and flaring of natural gas15.

Figure 1: Pattern of methane emissions from the Oil and Gas sector in Nigeria.

Source: PIK, Climate Watch, (Author’s Analysis)

Nigeria’s Commitment to Mitigating and Reducing Methane Emissions

In the past few years, Nigeria has taken a leading role on global and regional stages in implementing measures to address emissions from the Oil and Gas sector. In the regulatory context, the enactment of the methane mitigation guidelines16 is a major leadership stride at the regional and continental levels. Internationally, Nigeria is a member of the Global Gas Flaring Reduction Partnership (GGFR) and a supporter of the Zero Routine Flaring by 2030 initiative. Data from an initiative led by the World Bank showed that Nigeria has successfully reduced natural gas flaring by approximately 70% since 200017. While this is a significant achievement of the operational leadership, there is still room for improvement, as Nigeria ranked among the top 10 countries flaring gas globally in 2020, with ~7.2 billion cubic meters of gas still being wasted18.

To demonstrate Nigeria’s commitment to detect, measure, quantify, and reduce gas flaring, the National Oil Spill Detection and Response Agency (NOSDRA), serving as the environmental regulator in Nigeria’s Oil and Gas sector, developed the Nigerian Gas Flare Tracker (NGFT) in 201819. Data from the NGFT provides the Federal Government of Nigeria with a transparent transformational data tool to measure gas flare and emissions from on- and offshore oil and gas assets in Nigeria. NOSDRA is currently at the stage of developing a Satellite-based Methane Emission Tracker (SMET) prototype for Nigeria to serve as an independent data-gathering/benchmarking tool for the Measurement, Reporting, and Verification (MRV) of emissions in the sector.

As part of its commitment to reduce methane emissions, in 2019 Nigeria released its National Action Plan to decrease Short-Lived Climate Pollutants (SLCP)20. Additionally, the country has joined the Global Methane Alliance21, committing to absolute methane reduction targets of at least 45% by 2025 and 60-75% by 203022. The incorporation of specific methane reduction goals in Nigeria’s updated 2021 Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) demonstrates a clear objective of reducing fugitive methane emissions by 60% by 203123. Likewise, the full implementation of the measures outlined in the SLCP Plan has the potential to achieve a 61% reduction in methane emissions by the year 203024.

Nigeria's ability to regulate methane emissions from the Oil and Gas sector resulted from the integration of action on SLCPs into its national development planning and NDC. This involved collaboration with stakeholders responsible for national budgeting, development, investment planning, and institutional coordination. The establishment of the SLCP National Action Plan ensured that the plan's 22 SLCP Mitigation Measures became integral to Nigeria's achievement of its NDC goals.

The Nigeria Upstream Regulatory Petroleum Commission (NURPC) is responsible for the development, implementation, and monitoring of methane mitigation guidelines. This process included the establishment of a baseline for fugitive methane using the Country Methane Abatement Tool (CoMAT) and created a methodology and framework for reporting data on methane management.

The recent enactment and implementation of the Petroleum Industry Act (PIA, 2021) is currently strengthening methane mitigation initiatives in Nigeria. Concurrently, the implementation of key oil and gas policies are positioned to significantly reduce methane emissions. These include the Methane Emissions Reduction Guidelines; the Nigeria Gas Flare Commercialization Programme (NGFCP); Gas Flaring, Venting, and Methane Emissions (Prevention of Waste and Pollution) Regulations (2023); a proposal to review the PIA; harmonization of the hydrocarbon regulatory framework in Nigeria; and the development by NOSDRA of the Satellite-based Methane Emission Tracker.

As a result, the National Council on Climate Change (NCCC) is adopting a comprehensive, whole-of-government approach to coordinate methane mitigation efforts across all sectors. Serving as Nigeria's apex climate regulator and the nation's Global Methane Pledge (GMP) Champion, the NCCC is committed to enhancing actions to meet the NDC targets. To facilitate these efforts, the NCCC has established a "Methane Mitigation Technical Working Group25," which includes representatives from the government, regulatory bodies, and private operators. This group aims to create an enabling platform for achieving Nigeria's methane emissions reduction targets outlined in the Paris Agreement.

Policy and Implementation Coherence

On paper, existing Nigerian policies are somewhat coherent with its international commitments and national objectives for methane mitigation and reduction. The strategic effort of NOSDRA in developing a nationally acceptable transformational data tool (i.e., the Satellite-based Methane Emission Tracker-SMET) is aimed at detecting, measuring, and quantifying methane emissions for regulatory action26. The NUPRC Guidelines for Management of Fugitive Methane and Greenhouse Gases Emissions in the Upstream Oil and Gas Operations in Nigeria (NUPRC Guide 0024 - 2022) are aligned with the Global Methane Pledge27. The 2050 Long-Term Vision for Nigeria (LTV-2050) and the Energy Transition Plan (ETP)28 also emphasize the importance of reducing methane emissions and achieving net-zero emissions. The National Action Plan, aimed at achieving a 61% reduction in SCLP and methane emissions by 2030, laid the foundation for Nigeria NDC goals, targets, and strategies to address climate change. The NDC update sets a goal of reducing emissions by 60% from 2010 levels by 2030. Notably, both initiatives are consistent with the commitment made to the Global Methane Alliance, which targets a reduction of 60-70% in methane emissions by the year 2030.

ES2: Assessment of National Policies with International Commitments and Pledges

| National Policies/Action Plans | Alignment with International Commitments and Pledge | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UNFCCC | OGMP | CCAC | GMI | GMA | GGFR | |

| Nationally Determined Contributions | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Nigeria's 2050 Long-Term Vision (LTV-2050) | ✔ | ✔ | ||||

| Nigeria’s Climate Change Policy (NCCP) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Nigeria's National Action Plan for Short-Lived Climate Pollutants (SLCPs) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Nigeria’s Energy Transition Plan | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| National Oil Spill Contingency Plan (NOSCP) | ✔ | ✔ | ||||

| Guidelines for Management of Fugitive Methane and Greenhouse Gases Emissions in the Upstream Oil and Gas Operations in Nigeria (NUPRC Guide 0024 - 2022) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

Source: Author’s construct (2024)

Note: Alignment of policies was derived from national policy documents with specific sections and content that emphasized the need and target to address methane emissions generally or from specific sectors. The SLCP is an important document for this analysis viz-a-viz UNFCCC’s mission and other global initiatives.

However, while certain initiatives align with national global climate objectives for methane mitigation and reduction there are inconsistencies and gaps that hinder a seamless and comprehensive policy and implementation approach. These are outlined below:

Key Stakeholders in the Governance and Implementation of Methane Mitigation and Reduction Policy in Nigeria

The Nigeria Upstream Regulatory Petroleum Commission (NURPC) have made efforts to develop methane mitigation guidelines and monitor their implementation. However, other stakeholders play crucial roles in the planning, development, operations, and implementation of policies and projects. These stakeholders include government agencies, oil and gas companies, local communities, environmental and non-governmental organizations, academic and research institutions, regulatory bodies, financial institutions, labor unions, and technology and service providers. They can be grouped together as follows:

ES3: Landscape of broad Methane Mitigation and Reduction multi-stakeholders in the Oil and Gas sector. (Source: Table developed by author for contextual analysis)

| Policy Stakeholders, Technical, Commercial, and Environmental Regulators | Oil and Gas Operators, Production, Processing, Transmission/Storage, and Distribution | Science & Technology Innovation (Research and Development) | Civil Society Organizations, Host Communities, and the International Community |

Understanding and involving these stakeholders in a collaborative approach is essential for the design and sustainable implementation of policies that are aligned with the needs, priorities, and contextual realities of Nigeria.

Challenges Hindering Methane Mitigation Efforts

Despite international commitments and growing recognition of methane's harmful impact on the climate and healthand wellbeing, there are several obstacles that hinder effective mitigation and reduction efforts. For example, technical limitations, such as inadequate data on emission sources and volumes, limit the ability to prioritize and measure progress. Additionally, the lack of infrastructure for leak detection and repair, coupled with technological limitations in capturing and utilizing methane, further hinder progress.

Economic and financial challenges also play a significant role. The high costs of mitigation technologies and the absence of financial incentives discourage investments, especially when competing with other operational priorities. Additionally, weak regulatory frameworks and limited enforcement capacity create loopholes that hinder compliance and effective control of emissions.

Addressing these challenges requires a comprehensive approach. Improving data collection, investing in technology and infrastructure, as well as reviewing, amending, harmonizing, and strengthening the regulatory framework are crucial first steps. Building capacity through training programs and fostering collaboration among stakeholders are equally important. Finally, raising public awareness and engaging local communities will garner support and overcome potential resistance, ultimately leading to a cleaner future for Nigeria. Achieving a harmonized strategy necessitates bridging these gaps and ensuring that policies and actions collectively contribute to a robust and unified effort in mitigating methane emissions in the Oil and Gas sector.

Navigating the Way Forward

Nigeria has made a significant effort in reducing methane emissions from its Oil and Gas sector. However, to further accelerate progress to achieve its ambitious targets, the country needs to navigate a path forward that addresses current challenges and leverages promising opportunities. It can achieve this by enhancing collaboration between government agencies, industry stakeholders, and civil society organizations to develop and implement comprehensive methane reduction strategies. Moreover, effective methane emissions mitigation and reduction efforts within Nigeria's Oil and Gas sector necessitates a robust foundation built on meticulous research and active stakeholder engagement. Research is especially important for dissecting the intricacies of existing laws, regulations, guidelines, and legislation, ensuring a coherent and effective framework for methane mitigation. Stakeholder engagement, on the other hand, plays a pivotal role in extracting valuable insights from both state and non-state actors, providing a realistic portrayal of the sector's current status through constructive inputs and interactions. This dual approach not only enhances the understanding of the complexities involved but also sets the stage for the seamless integration of methane reduction strategies into Nigeria's energy transition plan and broader climate and development goals.

Endnotes

1U.S. Department of State. (2023). Highlights from 2023 global methane pledge ministerial. Fact Sheet-Office of the Spokesperson-Press Releases. Retrieved from https://www.state.gov/highlights-from-2023-global-methane-pledge-ministerial/#:~:text=This%20year%2C%20Global%20Methane%20Pledge,in%20investment%20to%20reduce%20methane.

2African Development Bank Group. (2022). Methane in Africa - A high-level assessment of anthropogenic methane emissions in Africa with case studies on potential evolution and abatement. Retrieved from Norway: https://www.afdb.org/sites/default/files/documents/publications/afdb_-_methane_in_africa.pdf

3United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). (2023). Methane Alert and Response System (MARS). Retrieved from https://www.unep.org/explore-topics/energy/what-we-do/methane/imeo-action/methane-alert-and-response-system-mars

4COP28 UAE. (2023). Oil & gas decarbonization charter launched to accelerate climate action. Retrieved from https://www.cop28.com/en/news/2023/12/Oil-Gas-Decarbonization-Charter-launched-to--accelerate-climate-action

5Barnard, P., Moomaw, W. R., Fioramonti, L., Laurance, W. F., Mahmoud, M. I., O’Sullivan, J., . . . Ripple, W. J. (2021). World scientists’ warnings into action, local to global. Science Progress, 104(4), 00368504211056290.

6Cointe, B., & Guillemot, H. (2023). A history of the 1.5° c target. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 14(3), e824.

7Global Methane Pledge (GMP). (2023). Fast action on methane to keep a 1.5°c future within reach. Retrieved from https://www.globalmethanepledge.org/

8United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). (2019). Oil and gas sector can bring quick climate win by tackling methane emissions. Retrieved from https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/oil-and-gas-sector-can-bring-quick-climate-win-tackling-methane-emissions

9United Nations. (2022). Sustainable development goals (SDGs)-transforming our world - the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Retrieved from https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/topics/sustainabledevelopmentgoals

10Federal Ministry of Environment. (2018). Short-Lived Climate Pollutants (SLCPs) national action plan (snap). Retrieved from Abuja: https://www.ccacoalition.org/en/resources/nigeria%E2%80%99s-national-action-plan-reduce-short-lived-climate-pollutants

11Federal Ministry of Environment. (2018). Short-Lived Climate Pollutants (SLCPs) national action plan (snap). Retrieved from Abuja: https://www.ccacoalition.org/en/resources/nigeria%E2%80%99s-national-action-plan-reduce-short-lived-climate-pollutants

12Federal Ministry of Environment. (2018). Short-Lived Climate Pollutants (SLCPs) national action plan (snap). Retrieved from Abuja: https://www.ccacoalition.org/en/resources/nigeria%E2%80%99s-national-action-plan-reduce-short-lived-climate-pollutants

13Federal Ministry of Environment. (2018). Short-Lived Climate Pollutants (SLCPs) national action plan (snap). Retrieved from Abuja: https://www.ccacoalition.org/en/resources/nigeria%E2%80%99s-national-action-plan-reduce-short-lived-climate-pollutants

14Climate Watch. (2022). Nigeria national context: What climate commitments has Nigeria submitted? Retrieved from https://www.climatewatchdata.org/countries/NGA?end_year=2020&start_year=1990

15National Oil Spill Detection and Response Agency (NOSDRA). (2022). Prospects of the Nigerian gas flare tracker in accelerating emission data gathering in Nigeria’s oil and gas sector for improved climate action. Paper presented at the UNFCCC Conference of Parties (COP27) Sharm El-Sheikh, International Conference Center, Egypt.

16International Energy Agency (IEA). (2022). Guidelines for management of fugitive methane and greenhouse gases emissions in the upstream oil and gas operations in Nigeria. Retrieved from https://www.iea.org/policies/16952-guidelines-for-management-of-fugitive-methane-and-greenhouse-gases-emissions-in-the-upstream-oil-and-gas-operations-in-nigeria

17James, O. (2019). Putting out the fire: How Nigeria has quietly cut flaring by 70%. Retrieved from https://www.ccap.org/post/putting-out-the-fire-how-nigeria-has-quietly-cut-flaring-by-70

18World Bank Group. (2023). Global gas flaring tracker report. Retrieved from Washington DC: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/extractiveindustries/publication/2023-global-gas-flaring-tracker-report

19National Oil Spill Detection and Response Agency (NOSDRA). (2018). Explore Nigeria Gas Flare Tracker Data. Retrieved 06 January 2014, from NOSDRA: https://nosdra.gasflaretracker.ng/gasflaretracker.html

20Federal Ministry of Environment. (2018). Short-lived climate pollutants (SLCPs) national action plan (SNAP). Retrieved from Abuja: https://www.ccacoalition.org/en/resources/nigeria%E2%80%99s-national-action-plan-reduce-short-lived-climate-pollutants

21Climate and Clean Air Coalition (CCAC). (2020). Nigeria and Cote d’Ivoire join global methane alliance, a critical move in fighting global warming. Retrieved from https://www.ccacoalition.org/news/nigeria-and-cote-divoire-join-global-methane-alliance-critical-move-fighting-global-warming

22Clean Air Task Force (CATF). (2022). Nigeria announces rules to reduce methane emissions from the oil and gas sector. Retrieved from https://www.catf.us/2022/11/nigeria-announces-rules-reduce-methane-emissions-oil-gas-sector/

23Federal Government of Nigeria (FGN). (2021). Nigeria's Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC). Retrieved from Abuja: https://climatechange.gov.ng/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/NDC_File-Amended-_11222.pdf

24Federal Ministry of Environment. (2018). Short-lived climate pollutants (SLCPs) national action plan (SNAP). Retrieved from Abuja: https://www.ccacoalition.org/en/resources/nigeria%E2%80%99s-national-action-plan-reduce-short-lived-climate-pollutants

25Clean Air Task Force (CATF). (2022). Nigeria announces rules to reduce methane emissions from the oil and gas sector. Retrieved from https://www.catf.us/2022/11/nigeria-announces-rules-reduce-methane-emissions-oil-gas-sector/

26NOSDRA: Director General (DG) (Producer). (2022). NOSDRA to develop satellite tracking tools for methane emission [Video]. Retrieved from YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3wq3WmxMJ1I

27Federal Government of Nigeria (FGN). (2018). Gas Flare (Prevention of Waste and Pollution) Regulations 2018. Lagos: Nigerian Upstream Petroleum Regulatory Commission (NUPRC). Retrieved from https://www.nuprc.gov.ng/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/GAS-FLARING-REGULATIONS.pdf.

28Federal Government of Nigeria (FGN). (2021a). 2050 long-term vision for Nigeria (ltv-2050). Retrieved from https://unfccc.int/documents/386681

29The Energy Transition Office (ETO). (2023). Nigeria's pathway to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060. Retrieved from https://energytransition.gov.ng/

30Department of Climate Change (DCC)- Federal Ministry of Environment (FMEnv) (2021). 2050 long-term vision for Nigeria (ltv-2050). Retrieved from Abuja: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/Nigeria_LTS1.pdf

About the Author

Dr. Mahmoud Ibrahim Mahmoud

Dr. Mahmoud Ibrahim Mahmoud is an accomplished Geospatial Information and Environmental Scientist specializing in satellite remote sensing and Geographic Information System (GIS) applications. He is currently a Senior Climate Change Fellow working on Methane Mitigation and Reduction in Nigeria with the Africa Policy Research Institute (APRI). His research interests include emission detection, gas flare, spatial land-use planning, urban ecology, methane emission reduction for climate change mitigation, and environmental sustainability.