Summary

- The health and well-being of humans and our planet risk further deterioration if drastic measures are not implemented to address climate change impacts and the societal and systemic gender inequalities associated with it.

- While gender has been integrated into national and global climate and sustainable development policies, a lack of comprehensive intentional and concrete gender action, especially at the local level, risks exacerbating past and current gender and climate injustices.

- Given the intersection of climate change and gender, coherent policies across the economic, environmental, social and cultural spheres are needed to provide an enabling environment for sustained progress.

- The lack of intersectional and gender-disaggregated data and research undermines efforts to design gender-responsive actions that enable women to cope with and adapt to climate change impacts.

- The dominant discourse that still represents women as victims of climate change is a missed opportunity for climate and sustainable development action, particularly in Africa where adaptation actions are urgently needed and where positive sustainable solutions are increasingly led by women.

Introduction and background

The intersection between gender inequalities and climate change risks and vulnerabilities is increasingly recognised as a critical issue by researchers and policymakers alike. Climate change does not affect everyone equally; the impacts are influenced by factors such as gender, age and socioeconomic status. According to the IPCC, marginalised populations, particularly the poor—of whom 54-63% are women—are the most likely to be adversely impacted by climate change, especially in developing countries.1 To put this disparity into perspective, the United Nations estimates that 80% of people displaced by climate-related impacts are women and girls.2 These statistics illustrate how climate change can exacerbate existing gender inequalities, intensifying the vulnerabilities of those who are already disadvantaged.

It is crucial to understand that while gender inequalities exist independently of climate change, climate change often serves to magnify these inequities. Cascading events such as the COVID-19 pandemic, ongoing geopolitical conflicts and increasing climate disasters have not only impacted socioeconomic conditions but also deepened gender inequalities, significantly affecting women’s progress toward equality.3 These gender-based barriers and socioeconomic burdens have been known to limit women's abilities to live the lives they desire, to participate in climate action, and to cope, adapt and build resilience to the growing impacts of climate change. Recent estimates suggest it could take up to 134 years to close the global gender gap, highlighting how urgent the situation is.4 To address these intersecting issues, stronger commitments and gender-responsive strategies are needed at both national and global levels, including at international climate forums like the COPs.

Gender inequalities and climate change

Gender inequalities do not occur in isolation, they are deeply embedded in the broader societal structures that shape our lives. But what exactly does this mean, and how do these inequalities manifest in the day-to-day lives of women? How do these disparities make women more vulnerable to the impacts of climate change? This section will explore these questions by providing an overview of how gender inequalities manifest across various social and economic contexts. It will examine how climate change exacerbates these existing disparities, acting as a multiplying factor that increases women's vulnerability. Additionally, this section will highlight how these compounded inequalities limit women's ability to cope, adapt and thrive in an increasingly volatile climate, ultimately underscoring the need for gender-responsive climate action.

Economic inequalities

Economic arrangements, opportunities and outcomes have both positive and negative influences on gender equality. Economic growth has created some value for gender equality. For instance, from 2000 to 2022, women's labour force participation rose by 11 percentage points in OECD countries, contributing 0.37 percentage points to average annual economic growth.5 These numbers were much higher in sub-Saharan Africa, where female labour participation rates ranged between 60-65% in 1991 to 2022.6 However, structural barriers such as unequal and limited opportunities for women, wage gaps (the global gender pay gap, which has remained stagnant at 16%, with women in some countries earning up to 35% less than men for the same work7), and limited access to capital and leadership roles have continued to have negative impacts on the outcomes and enjoyment of economic benefits for women, especially in the Global South.8 When women participate in the formal labour force, they are often in lower-paying and less secure jobs, which limits their full potential and enjoyment of economic benefits.

Where and how women participate in the workforce also matters. An estimated 740 million women work in the informal economy globally9 and in developing economies, 70% of women’s employment comes from informal work. Evidence also suggests that entry into paid work does not reduce their unpaid work responsibilities so that paid work is often on top of the work that they do at home, which goes largely unrecognised and undervalued. This also results in longer working hours for women than men and greater time poverty.

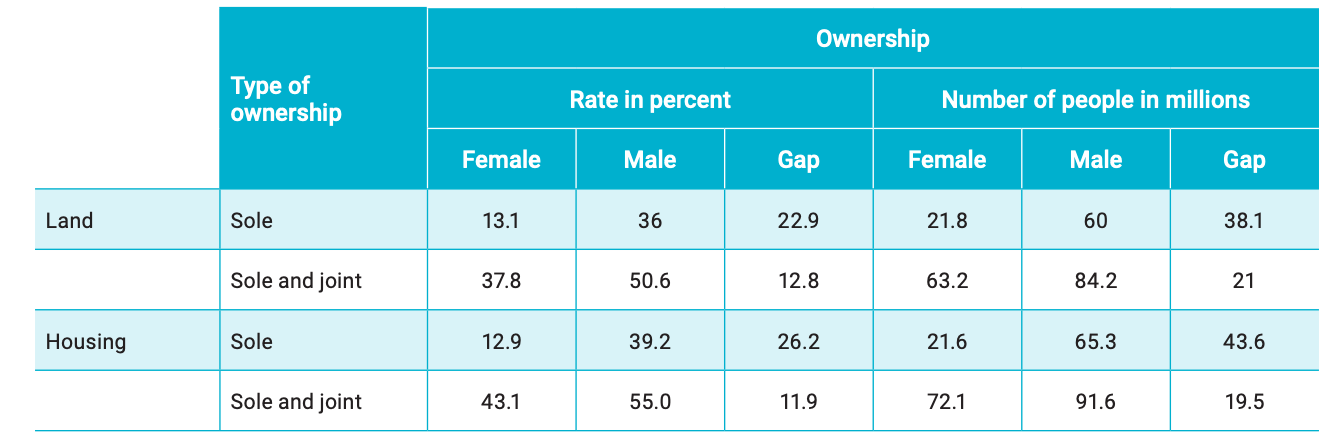

Lastly, women lack the same economic rights as men, with women less likely than men to own property, and to have access to resources, credit, agricultural inputs, technology, decision-making structures, training and extension services.10

Source: Global Center on Adaptation (GCA). (2021). State and Trends in Adaptation Report 2021. Global Center on Adaptation. https://gca.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/GCA_STA_2021_Complete_website.pdf

These inequalities leave women highly vulnerable to exploitation, insecure and in low-paying jobs that limit their economic empowerment to fully participate in climate change action or protect themselves and their loved ones from harm when climate disasters occur.

Overrepresentation in paid and unpaid care work

The care sector, which includes health, education and household services, employs around 381 million workers worldwide, making up 11.5% of global employment. Of these workers, two-thirds are women.11 Women’s overrepresentation in the care workforce highlights systemic gender inequalities, including wage disparities and undervaluation of care work. Climate change impacts worsen the periods and intensity of care work, particularly in families affected by environmental disasters. Moreover, women are responsible for 76.2% of unpaid care work globally.12 This includes household chores, caregiving for children, the elderly and other family members, with women from vulnerable social, economic and environmental backgrounds bearing the greatest burden of unpaid care work. These inequalities limit women’s access to quality employment, financial independence and the opportunity to participate in social and economic activities and climate action.13 Climate change also exacerbates the burdens of paid and unpaid care work. For example, it is estimated that by 2050, climate change could increase the time women spend collecting water in households by up to 30% globally,14 leading to significant losses of time otherwise used for education, work or leisure.15 These inequalities not only negatively impact women´s economic and societal progress,16 they also influence women's participation in climate action and their ability to adapt and build resilience to climate change.

Dependence on climate-sensitive sectors and resources

The areas experiencing the greatest impacts of climate change are also those that women depend on the most for their lives and livelihood opportunities. In sub-Saharan Africa for example, over 60% of employed women work in the agriculture sector17 and contribute 60-80% of food production. While women in the agriculture sector are just as efficient as men, they have less output because they control less land, use fewer inputs and have less access to labour and services like agricultural extension.18

Table 2. Gender disparities in agricultural labor and land ownership by region

| Region | % of Agricultural Labour Performed by Women | % of Agricultural Land Owned by Women |

|---|---|---|

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 48.7% | 15% |

| Asia (excluding Japan) | 42% | 11% |

| Latin America | 20% | 18% |

| Middle East and North Africa | 40% | 5% |

Source: Land Links, USAID. (2016). Fact Sheet: Land Tenure and Women’s Empowerment. USAID https://www.land-links.org/issue-brief/fact-sheet-land-tenure-womens-empowerment/

These inequalities have an unprecedented impact on food insecurity which disproportionately affects women. Current estimates show that 240 million more women and girls will experience food insecurity caused by climate change, compared to 131 million more men and boys.19 This disparity is especially pronounced in regions like Central Africa and Yemen, where women and children face severe food insecurity.20 Rural women are especially vulnerable because of the shrinking resources as a result of climate change, which means that they need to work harder and longer, often in dangerous conditions,21 to access basic needs and services, resulting in unprecedented impacts on their capabilities, health and wellbeing.

Poverty

The majority of the world's poor are women and according to UN Women, the added burdens of climate change could push nearly 160 million women and girls into poverty by 2050.22 The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated these inequalities, with 388 million women and girls living in extreme poverty in 2022, with projections indicating that this number could rise to 446 million.23 Poverty diminishes adaptive capacityand limits the freedom, ability andcapacity to make desired and sustainable consumption and lifestyle choices. These groups also lack the resources needed to limit andadapt to harsh climatic impacts (e.g. weather information,stable housing, insurance, access to safe drinking water and sanitation, and transportation). Moreover, the limiting factors of poverty play a role in women's inability to anticipate and respond to climate change impacts, as well as to contribute to adaptive capacity, resilience building and broader climate actions.

Energy inequalities

Energy poverty, defined as a household’s lack of access to essential energy services needed for a decent standard of living,24 disproportionately affects women and girls. It is projected that by 2030, around 660 million people will still lack electricity access, with sub-Saharan Africa accounting for 83% of this deficit.2 Moreover, globally, 2.3 billion people still use highly polluting cooking methods due to the lack of access to clean cooking facilities.26 As with the lack of electricity, the lack of clean cooking services is more pronounced in African countries, where the International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that four out of five Africans cook over open fires or traditional stoves, contributing to severe health risks.27 Women are especially vulnerable. Traditional gender norms often place the responsibility of cooking and other household energy-dependent duties on women and girls. Their lack of access to modern energy sources exposes them to extreme danger and limits their social and economic development. For example, women accounted for over 60% of the 3.7 million deaths attributable to household air pollution in 2022.28 Without electricity or modern energy sources, household tasks become more physically and mentally demanding, and women often prioritise these duties over their educational and economic opportunities. As a result, energy poverty perpetuates gender inequalities, further entrenching traditional gender roles29 and limiting women's ability to cope with the growing impacts of climate change.

Exclusion and underrepresentation

Women are also often excluded from political, community and household decision-making processes that affect their lives. It was found that in 2020, only 25% of parliamentarians globally were women.30 Representation in sub-Saharan Africa increased slightly from 9.8% in 1995 to 24.7% in 2020. However, since then, women’s representation in half of the African countries was still below 20%.31 Women are also underrepresented in political decision-making processes and the education sector, specifically in STEM-related fields (science, technology, engineering and mathematics); areas that can boost women's capabilities and skills to secure and well-paid jobs. Women's perspectives are also less likely to be taken into consideration in decision-making processes, which leads to a lack of female perspectives in addressing societal issues, including climate change action. This exclusion increases the disconnection between policy prescriptions and the realities of women resulting in failure, rejection or unsustainable actions.

An overview of gender-responsive climate action

The burdens of these inequalities are not lost to national governments and the global community. Several attempts have been made to address them. The first widely recognised attempt to incorporate and address the nexus between gender and climate change came in 1991, at the WEDO - World Women's Congress for a Healthy Planet in Miami. Here, the Women's Action Agenda 21 was adopted, which laid the foundation for women's attempts to significantly impact the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (Earth Summit) in Rio de Janeiro the following year. Recognising women's roles in addressing climate change issues and aiming to ensure gender equality in crucial weather and climate contexts, UNITAR, the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) Secretariat, with support from UN Women, announced the launch of a Womens' Leadership Programme at COP20 in Lima.32 The COP established the first Lima work programme on gender (LWPG) (Decision 18/CP.20) to advance gender balance and integrate gender considerations into the work of Parties and the secretariat in implementing the Convention.33 This marked the first reference to gender equality in a COP decision and the first standalone decision that contributed to the advancement of gender equality across all areas of climate negotiations.34

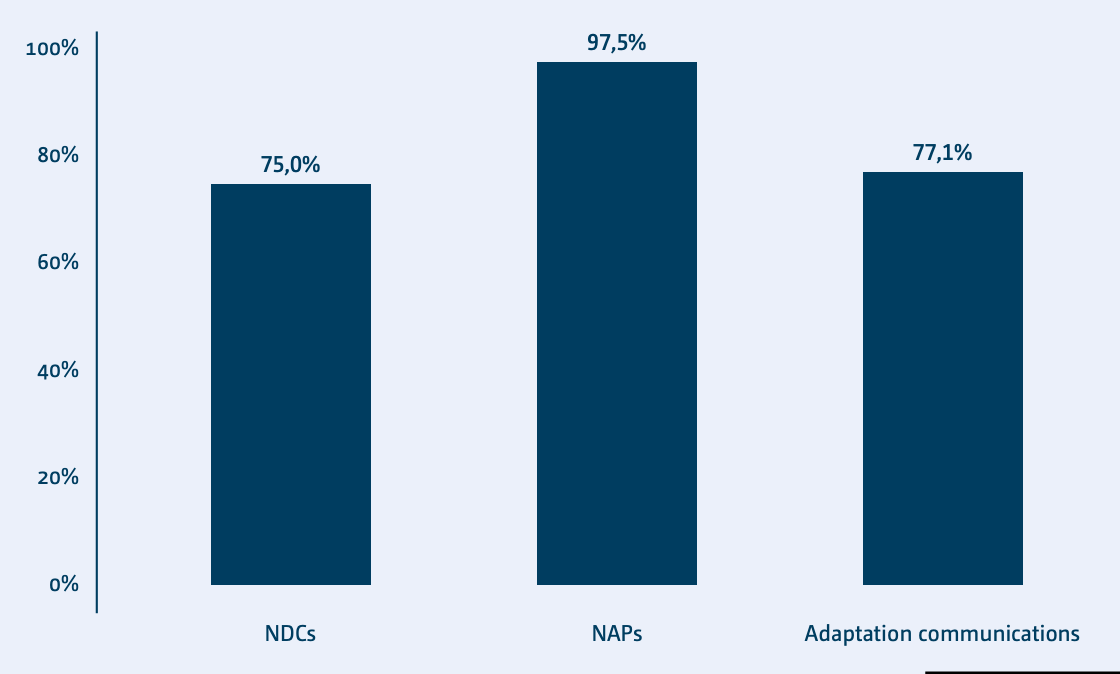

The following year, The Paris Agreement, adopted at COP21 marked another important step in the gender and climate change nexus by establishing a mandate for promoting the inclusion of gender equality into adaptation measures and capacity-building initiatives. Following the adoption of the Paris Agreement, all Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change UNFCCC are required to submit their national climate action pledges, known asNationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), every five years. As reflected in National Adaptation Plans (NAPS) within the NDCs (See Fig.1), parties have increasingly applied a gender-responsive approach to adaptation planning and implementation. The regions that most frequently included gender or considerations of women in their NDCs were Latin America and the Caribbean, sub-Saharan Africa, and Asia and the Pacific.35

Source: United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). (2023). Progress, good practices and lessons learned in prioritizing and incorporating gender-responsive adaptation action. UNFCCC. https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/202310_adaptation_gender.pdf

The same year, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were universally adopted to address, among other issues, poverty, inequality and climate goals.36 The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030 also provides a roadmap for building safer, more resilient communities. To support its implementation, the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR) launched the Gender Action Plan, known as the ‘Sendai GAP’, which aims to address gender discrimination and inequality in disasters. The Action Plan seeks to accelerate the implementation of gender-responsive disaster risk reduction by increasing resources, activities and impacts, with a goal of reducing gender-related disaster risk by 2030.37 On finance, the Green Climate Fund (GCF), the world’s largest climate fund, supports developing countries' Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) with a gender-sensitive approach,38 incorporating a gender policy and action plan into its operation.

Gender and climate justice action at the COPs

COP28 witnessed the first-ever Gender Day, with high-level dialogues that culminated in the announcement of a new Gender-Responsive Just Transitions & Climate Action Partnership from the COP28 Presidency. Endorsed by over 60 parties, the partnership includes a package of commitments, such as actions on data, finance and equal opportunities. In particular, the partnership centres around three core pillars: better quality data to support decision-making in transition planning, more effective finance flows to regions most impacted by climate change, and education, skills and capacity building to support individual engagement in transitions. This year’s COP Gender Day will take place on 21 November 2024. To be effective, negotiations must resist getting hung up on sensitivity to gender differences, and instead seek to build on the momentum created at COP28 with specific action points on:

- Finance

To date, substantial amounts have been pledged. A first step would be to honour these outstanding pledges. In addition to honouring past pledges and increasing financial flow, women's financial inclusion and access must be guaranteed. Budgets must explicitly designate lines for assisting with the implementation of gender-related activities and enlisting the help of technical specialists to build women's capabilities to adapt, mitigate and build climate resilience.39 Moreover, financial inclusion and access should strategically be targeted to sectors and initiatives where women are most involved, and in areas with positive multiplier effects such as education, agriculture, fish processing, energy, and water, and food security. Support for women-owned and led businesses is another area that could benefit from targeted financial action at COP29 to close the gender gap in finance access. According to the SME Finance Forum, women-owned businesses make up 23% of micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) worldwide, but they also bear 32% of the USD 5 trillion financing gap.40 Closing this gap presents an opportunity for both climate and gender justice action.

- Just energy transition

The energy sector is another area where COP gender and climate negotiations can reap enormous benefits for women and broader society. A study in Nature Sustainability found that replacing wood and charcoal-burning stoves with cleaner alternatives could prevent 463,000 deaths annually in sub-Saharan Africa and save USD 66 billion in healthcare costs.41 Access to modern and clean energy services is also known to have positive social, health, wellbeing and climate outcomes. In Mali, electricity access improved girls' school attendance and performance, while in Bangladesh, school attendance rose and literacy rates were 20% higher among women with electricity at home.42 The energy sector also presents an untapped opportunity to improve women’s and broader societal and economic outcomes. Women’s access to quality jobs and financing in the energy sector is vital for empowering them and their families. Recent research from the McKinsey Global Institute (MGI) finds that if women were to participate in the economy ‘identically to men’, they could add as much as USD 28 trillion, or 26%, to annual global GDP (roughly the combined size of the current US and Chinese economies) by 2025.43 However, women hold less than a third of jobs in the renewable energy sector and only 22% of technical roles.44 To tap into these opportunities, gender negotiations should not only be limited only to Gender Day. Instead, negotiators must seek to integrate and underscore the interlinkages between gender, climate and sustainable development actions.

- Research and data

Funding research and data is another area of opportunity for climate and gender justice at COP29. Data and context-specific research is needed to pinpoint gender gaps and create policies and implementation processes that help close them. In the context of the growing climate crisis, data is crucial for understanding the dimensions and intersectionality of gender and climate inequalities. There should also be investment into gender-sensitive needs assessment strategies and costing. Moreover, spotlighting existing local and women-led initiatives that achieve desired outcomes can help draw lessons from community-based or locally-led actions to inform broader climate policy and implementation actions. This kind of evidence is also crucial for increasing attention and demanding increased political responsibility and actions on gender and climate change injustices at the local, national and global levels.

Conclusion

Climate change impacts on the health and well-being of communities, especially of women and girls, are complex and diverse, defying simple, one-size-fits-all frames, narratives and actions. As this analysis has shown, gender inequalities involve more than the lack of equal access to resources and opportunities to maintain or improve livelihoods and well-being outcomes. For these reasons, providing equal resources and opportunities, or just climate solutions for all, is not sufficient. Whether it is with climate action or sustainable development goals, true gender equality can only be achieved through the process of equity, which involves accounting for systemic and historical forms of injustices and inequalities that are known to influence how women experience and deal with climate change. In other words, creating environments where they build capabilities and freedoms to realise their full potential when they choose to.

Importantly, women are not a homogenous category. Hence, the intersectional approach should be applied when assessing gender-based needs, planning and costing. This requires the inclusion of diverse stakeholders to draw rich, varied visions and knowledge to support the development of fit-for-purpose policies and implementation strategies, so that no one is left behind. As progress is sought at COP29 and beyond, it is critical that policies and strategies for climate and sustainable development don’t continue to amplify existing inequalities by looking at gender and climate justice through narrow frames. Beyond the COPs, coordination across sectors is key for maximising synergies and creating enabling environments to amplify and sustain progress toward equality and resilience.

Endnotes

[1] Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). (2007). Climate Change 2007: Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the IPCC. Cambridge University Press. https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/03/ar4_wg2_full_report.pdf

[2] United Nations. (2021). Women bear the brunt of the climate crisis, COP26 highlights. UN News. https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/11/1105322

[3] Alon, T., Doepke, M., Olmstead-Rumsey, J., & Tertilt, M. (2020). The Impact of COVID-19 on Gender Equality (w26947; p. w26947). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w26947

[4] World Economic Forum. (2024). Global Gender Gap 2024: Insight Report. World Economic Forum. https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2024.pdf

[5] Fluchtmann, J., Adema, W., & Keese, M. (Eds.). (2024). Gender equality and economic growth: Past progress and future potential. OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 304, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/fb0a0a93-en

[6] Ortiz-Ospina, E., Tzvetkova, S., & Roser, M. (2018, March). Women’s Employment. Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/female-labor-supply

[7] United Nations. (2019). Policy Brief: The Impact of COVID-19 on Women. United Nations. https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/policy_brief_on_covid_impact_on_women_9_apr_2020_updated.pdf

[8] Fluchtmann, J., Adema, W., & Keese, M. (Eds.). (2024). Gender equality and economic growth: Past progress and future potential. OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 304, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/fb0a0a93-en

[9] Bonnet, F., Vanek, J., & Chen, M. (2019). Women and Men in the Informal Economy – A Statistical Brief. WIEGO. https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ed_protect/@protrav/@travail/documents/publication/wcms_711798.pdf

[10] Osman-Elasha, B. (2008, August 1). Women...In the shadow of climate change. UN Chronicle. United Nations. https://www.un.org/en/chronicle/article/womenin-shadow-climate-change

[11] International Labour Organization. (2023). Green Jobs, an Opportunity for Women in Latin America. Climate Change, Gender and Just Transition. ILO. https://www.ilo.org/publications/mainstreaming-care-work-combat-effects-climate-change

[12] International Labour Organization. (2018). Care work and care jobs for the future of decent work. International Labour Organization. https://www.ilo.org/publications/major-publications/care-work-and-care-jobs-future-decent-work

[13] Ibid.

[14] Carr, R., Kotz, M., Pichler, P.-P., Weisz, H., Belmin, C., & Wenz, L. (2024). Climate change exacerbates the burden of water collection on women’s welfare globally. Nature Climate Change, 14(7), 700–706. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-024-02037-8

[15] Ibid.

[16] Bertay, A. C., Dordevic, L., & Sever, C. (2020). Gender Inequality and Economic Growth: Evidence from Industry-Level Data. IMF Working Papers, 20(119). https://doi.org/10.5089/9781513546278.001

[17] Njobe, D. B. (n.d.). Women and Agriculture: The Untapped Opportunity in the Wave of Transformation. https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Events/DakAgri2015/Women_and_Agriculture_The_Untapped_Opportunity_in_the_Wave_of_Transformation.pdf

[18] Food and Agriculture Organization. (n.d.). The gender gap in agriculture and its implications on the context of climate change. https://www.fao.org/climate-smart-agriculture-sourcebook/enabling-frameworks/module-c6-gender/chapter-c7-2/en/

[19] UN Women. (n.d.). Data Driven Insights: The effects of Climate Change on Gender and Development. UN Women. https://www.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/2023-11/data-driven_insight_the_effects_of_climate_change_on_gender_development.pdf

[20] Marsh, J. (2023). Gender Equality in Agriculture Essential for Food Security. https://agrilinks.org/post/gender-equality-agriculture-essential-food-security#:~:text=The%20Food%20and%20Agricultural%20Organization,women%20and%20children%20is%20rampant.

[21] Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). (2024). FAO report: Heatwaves and floods affect rural women and men differently, widen income gap. FAO. https://www.fao.org/newsroom/detail/fao-report--heatwaves-and-floods-affect-rural-women-and-men-differently--widen-income-gap/en

[22] UN Women. (n.d.). Data Driven Insights: The effects of Climate Change on Gender and Development. UN Women. https://www.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/2023-11/data-driven_insight_the_effects_of_climate_change_on_gender_development.pdf

[23] UN Women. (2022). Poverty deepens for women and girls, according to latest projections. UN Women Data Hub. https://data.unwomen.org/features/poverty-deepens-women-and-girls-according-latest-projections

[24] Law Insider. (n.d.). Energy poverty Definition. Law Insider. https://www.lawinsider.com/dictionary/energy-poverty

[25] United Nations General Assembly & Economic and Social Council. (2024). Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goal. United Nations. https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/files/report/2024/SG-SDG-Progress-Report-2024-advanced-unedited-version.pdf

[26] International Energy Agency. (2023). A Vision for Clean Cooking Access for All. IEA. https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/f63eebbc-a3df-4542-b2fb-364dd66a2199/AVisionforCleanCookingAccessforAll.pdf

[27] Ibid.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Acheampong, A. O., Opoku, E. E. O., Amankwaa, A., & Dzator, J. (2024). Energy poverty and gender equality in education: Unpacking the transmission channels. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 202, 123274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2024.123274

[30] Global proportion of women in parliament hits record high. (2021). UN News. https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/in-focus/women-and-the-sdgs/sdg-5-gender-equality

[31] GCA. (2021). State and Trends in Adaptation Report. Accessed at https://gca.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/GCA_STA21_Sect3_GENDER.pdf

[32] United Nations Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR). (2014). Gender Day at COP 20/CMP 10: Announcing Women's Leadership Programme for 2015. UNITAR. https://unitar.org/about/news-stories/news/gender-day-cop-20cmp-10-announcing-womens-leadership-programme-2015

[33] United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). (2024). The enhanced Lima work programme on gender. UNFCCC. https://unfccc.int/topics/gender/workstreams/the-enhanced-lima-work-programme-on-gender

[34] Gama, S., Teeluck, P., & Tenzing, J. (2016). Strengthening the Lima Work Programme on Gender: Perspectives from Malawi and the CBD. International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED). https://www.iied.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/migrate/10165IIED.pdf

[35] United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). (2023). Progress, good practices and lessons learned in prioritizing and incorporating gender-responsive adaptation action. UNFCCC. https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/202310_adaptation_gender.pdf

[36] United Nations Development Program. (2016). Overview of linkages between gender and climate change. United Nations Development Program. https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/publications/UNDP%20Linkages%20Gender%20and%20CC%20Policy%20Brief%201-WEB.pdf

[37] United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. (2024). What is the Sendai Gender Action Plan? https://www.undrr.org/news/what-sendai-gender-action-plan

[38] Ibid.

[39] NDC Partnership. (n.d). Developing gender-responsive NDC action plans: A practical guide. NDC Partnership. https://ndcpartnership.org/sites/default/files/2023-09/gender-responsive-ndc-action-plans-practical-guide-march-2021_0.pdf

[40] PwC. (2021). State of climate tech 2021: Scaling breakthroughs for net zero. PwC. https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/services/sustainability/publications/state-of-climate-tech.html

[41] Ibid.

[42] Acheampong, A. O., Opoku, E. E. O., Amankwaa, A., & Dzator, J. (2024). Energy poverty and gender equality in education: Unpacking the transmission channels. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 202, 123274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2024.123274

[43] Woetzel, L., Madgavkar, A., Ellingrud, K., Labaye, E., Devillard, S., Kutcher, E., Manyika, J., Dobbs, R., & Krishnan, M. (2015, September 1). The power of parity: How advancing women’s equality can add $12 trillion to global growth. McKinsey & Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/employment-and-growth/how-advancing-womens-equality-can-add-12-trillion-to-global-growth

[44] International Renewable Energy Agency. (2024). Decentralised solar PV: A gender perspective. IRENA. https://www.irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Publication/2024/Oct/IRENA_Decentralised_solar_PV_Gender_perspective_2024.pdf

About the author

Dr. Grace Mbungu

Dr. Grace Mbungu is a Senior Fellow and the Head of the Climate Change Program at APRI, supporting policymakers with timely and evidence-based policy options to enable the creation of long-term, sustainable and inclusive wellbeing and livelihood opportunities. Before joining APRI, Dr. Mbungu was a fellow and research associate at the Institute for Advanced Sustainability Studies (IASS), now RIFs, in Potsdam, Germany. From Bowling Green State University (Ohio, USA), she holds a Bachelor’s degree in Political Science and Gender Studies as well as a Master’s degree in Public Administration, with a focus on human rights and international development. She holds a Doctorate from the University of Stuttgart, Germany.

Acknowledgement

I would like to extend my heartfelt thanks to Prof. Naila Kabeer, Professor of Gender and Development in the Department of International Development at the London School of Economics (LSE), where she is also on the Faculty of LSE’s International Inequalities Institute, for her review and invaluable feedback on the draft of this publication.