This article is part of a series of special thought pieces that APRI is publishing in partnership with the African Climate Foundation in the run up to COP26 in Glasgow. The series is titled From Rio 1992 to COP26: Africa’s Climate Journey and the Road Ahead.

Highlights

- In the Sub-Saharan Africa context, the energy transition cannot simply be about decarbonization. Importantly, it must be linked to the need to bridge the energy access gap and encourage productive uses of energy to create new competitive industrial clusters.

- The clear opportunities for green industrialization can co-exist with traditional resource-based industrialization to drive structural transformation.

- Linkages and value chain development are critical for avoiding the paradox of plenty syndrome as exporting raw minerals is no longer justifiable.

Introduction

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is clear about the human causes of climate change in its latest Sixth Assessment Report. The IPCC states that “it is unequivocal that the increase of CO2, methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O) in the atmosphere over the industrial era is the result of human activities and that human influence is the principal driver of many changes observed across the atmosphere, ocean, cryosphere and biosphere” (IPCC, 2021; p.17). The global energy sector is the biggest contributor to Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions and, thus, transforming it will be critical for mitigating emissions, realizing 2050 net zero-carbon targets and minimizing the impacts of climate change on humanity. Currently, around 73% of global GHG emissions come from energy use, with most emissions generated from fossil fuels.

To maintain global temperature below 1.5°C, the world must therefore drastically limit its fossil fuel use. Indeed, a recent analysis suggests that “60% of oil and fossil methane gas, and 90% of coal must remain unextracted to keep within a 1.5°C carbon budget” (Welsby et al., 2021: p.1). This suggestion is corroborated by the International Energy Agency (IEA) in its recent Net Zero by 2050 report, which determines that achieving the 1.5°C target necessitates “beyond projects already committed as of 2021, [that] there are no new oil and gas fields approved for development … and no new coal mines or mine extensions are required” (IEA, 2021; p.21)4.

While the desire and determination to switch global energy are not conjectural, the challenge is how to transition, and indeed at what rate, to avoid disrupting global economies and, in particular, to mitigate transition risks for developing economies. This challenge raises two important questions: (1) what will be the longer-term implications of the energy transition for Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA)?; and (2) can the region leverage clean industrialization to mitigate some of these transition risks?

Energy transitions and industrialization: can the transition to clean energy create new opportunities for industrialization on the continent?

Industrialization is not new to SSA. In the early post-independence days of the 1960s, countries such as Tanzania, Zambia, Ghana and Nigeria sought to industrialize their economies with varied success. The early policies sought to move these new nation states away from exploitative colonial enterprises by adding value to primary commodities before export and import substitution. Many of these initiatives, however, failed. Political instability and conflict — including successive military coups in some countries — and exogenous factors such as terms of trade shocks, like the 1970s oil crisis and commodity price decreases, all undermined long-term economic policymaking. Moreover, the Bretton Woods institutions further inhibited industrialization objectives, with the structural adjustment programs (SAPs) of the mid-1980s imposing restrictive economic reforms, including limiting the ability of countries to deploy import substitution. As a result, SSA remains the least diversified region in the world today, which, coupled with its integration into the global economy, has made it particularly vulnerable to external shocks.

In more recent times, the commodities price boom of the past 10-15 years created an important opportunity for SSA countries to use their resource revenues to diversify their economies. Unfortunately, this diversification did not materialise. The susceptibility of SSA economies has further been evidenced by the 2014-16 global commodities crash, and most recently, the COVID-19 pandemic, the impact of which is likely to linger in SSA for much longer than in other parts of the world.

African countries now have another, albeit small, window of opportunity to leverage the COVID-19 recovery and associated ‘green recovery’ programs to develop their need-specific green industrial strategies. For example, the IEA estimates that, to meet 2050 net zero targets, annual energy investment will need to increase to between US$4 and US$5 trillion by 2030 from the current US$2 trillion. Simply directing 10% of the US$50 trillion investment to SSA would bring significant benefits to the region. To put this into perspective, this potential US$5 trillion sum would amount to almost three times (2.96X) of the combined US$1.69 trillion GDP of SSA as of end-2020. Investments on this scale could spur a major economic boom and, if utilized wisely and as part of a broader industrial strategy, can deliver sustainable long-term development opportunities.

This paper suggests three strategies that African governments can practically promote to leverage the shift to clean energy and promote industrialization at the forthcoming 26th UN Climate Change Conference (COP26) in Glasgow from October 31 to November 12, 2021.

Policy Action 1: An explicit and well-defined commitment to industrial policy with long-term planning horizons and all stakeholders working towards the same goals

While labor, capital and entrepreneurship are critical inputs for any industry, for industrial policy to work on the continent, the necessary condition is an explicit commitment to industrial policy with long-term planning horizons and all stakeholders working towards the same end. African governments need a clearly defined and costed green industrial policy strategy with an action plan or roadmap and well-defined metrics for benchmarking progress. These industrial strategies will need to be reinforced by complementary policies — governance (institutions), education, infrastructure and trade policy openness — to support export diversification and competitiveness.

Drawing on lessons from the industrial success of the East Asia tigers, successful industrial policy also requires deliberate policies targeted at developing the capacity and capabilities of domestic firms, including fostering industrial clusters (agglomeration) via special economic zones such as industrial parks, high tech zones and export-processing zones. To attract both domestic and foreign capital, African countries can offer targeted tax incentives for companies to establish plants for the manufacturing and assembling of green energy technologies. So that the countries can benefit from the effects of learning by doing, innovation and agglomeration (which are important factors for increasing firm-level productivity), these incentives can be ring fenced for plants established in special industrial zones.

However, to unlock the broader catalytic impacts of non-enclave (locally owned and based) activities in manufacturing green technologies, industrial policies also need to prioritize research, innovation and development (RID) and technology and skills transfer. Currently, many SSA countries spend less than 1% of their GDP on research and development. Therefore, industrial policies should encourage entrepreneurs, governments and donor partners to fund targeted research and development (R&D) in universities and higher learning institutions. China took this approach with solar PVs and has positioned itself as a leading producer in just a decade. To enable technology transfer, China enticed foreign companies to set up solar PV manufacturing plants in-country, taking advantage of market access (large consumer base) and low production costs. However, they also ensured that Chinese staff were employed in manufacturing plants and learning about the technology. Some of these staff then set up local manufacturing plants using the skills and knowledge acquired, and with state support and access to the Chinese market were able to outcompete foreign companies in just ten years. Having strong elements of technology and skills transfer must therefore be built in conjunction with policies to support R&D capabilities. African countries can take advantage of their relatively low production-cost base and their access to a large untapped market to insist on tech and skills transfer as a reciprocal control measure for accessing tax incentives.

African countries will also need to prioritize regional collaboration and create linkages with other sectors as part of their industrial policies.

These processes will enable them to connect RID centers of excellence throughout the continent to identify context-specific but scalable engineering and technical solutions to meet Africa’s needs. These centers could, for example, lead to the scaling and mass manufacture of renewable energy (RE)-powered agri-equipment from locally designed and assembled solar-powered irrigation systems to combine harvesters, tills, shredders, dryers and warehouses. This development would drastically improve agricultural yields and reduce post-harvest losses.

Policy Action 2: Meeting the continent’s energy needs using all available energy resources

Reliable and affordable energy — and in particular electricity — is an essential precondition for economic growth. In SSA, access to reliable power is currently one of the biggest constraints to the continent’s development. About 46% or 600 million people in Africa currently lack access to electricity, while around 730 million lack clean fuels and cooking facilities. Further, for those with access to electricity, supply is often irregular, unreliable and unaffordable.

Within the energy trilemma of energy security, environmental sustainability and energy equity, achieving access to (including the affordability of) energy to address the current access deficit and support accelerated industrialization must be the priority for Africa. As the lowest contributor to GHG emissions, Africa should be entitled to its conventional and non-conventional energy resources to address its energy needs. In other regions, such as Europe, energy security is being prioritized through discussions about conventional coal and nuclear power plants being brought back online to address intermittency of supply from wind and high gas prices. Should SSA not be allowed to do the same?

Natural gas as a bridging fuel

Natural gas is an integral part of Africa’s energy future as a cost-effective fuel for delivering baseload power. It is also considered to be more environmentally friendly than other fossil fuels. Natural gas is already the primary fuel of choice for power generation in several countries. With an estimated reserve of 558 trillion cubic feet on the continent (the fourth-largest gas reserve holder after North America), this trend is likely to continue into the foreseeable future.

However, to realize the full benefits of the fuller gas value chain for power generation and other industrial uses, infrastructure financing is needed to evacuate gas from fields to the relevant domestic markets. Unlocking SSA’s gas value chain requires significant investment in trans-regional pipelines to evacuate gas to domestic markets and, to some extent, for liquefied natural gas exports too. With an expanded pipeline network in west, east and southern Africa, regional gas movements could double by 2030, further displacing coal in countries such as South Africa. Other constraints, including regulatory bottlenecks (ineffective gas pricing and non-payment risks), will also need to be addressed.

Deploying renewable energy technologies

RE-technologies, especially wind and solar, are also important in helping to bridge the continent’s electricity access deficit. Renewable costs have declined substantially over the past ten years and are now out-competing some conventional fuels as the least-cost alternative for new generation capacity.

This decline in costs has been complemented by a significant drop in the cost of utility-scale battery storage, thereby addressing the intermittency challenge and enabling the provision of dispatchable power. To leverage these benefits, both policy and market-based interventions (renewable obligations standards (RPS), feed-in-tariffs (FiTs), auctions, wind investment and tax credit and net metering ) will be needed to attract RE investors.

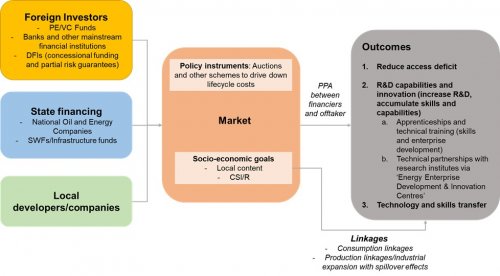

Fig 1: Renewable Energy Linkages Ecosystem. Source: Author's Construct

Policy Action 3: Deepening linkages in a new resource-based industrialization paradigm

Africa has an abundance of minerals needed to unlock the energy transition. Metals such as copper, lithium, nickel, cobalt, manganese and graphite are vital to the transition to more sustainable battery longevity and performance and to the energy density of all-electric vehicles (EV) motors, solar panels and wind turbines. The demand for these minerals and other rare earth elements is forecast to increase exponentially in the coming years. This rise in demand creates an opportunity for SSA, which holds an abundance of these mineral resources, to play a significant role in global supply to leverage its resource base to move up the value chain and position itself as a manufacturer of final clean products. Chile’s attempt at developing and capturing a larger share of the EV value chain can serve as a guide for SSA. In March 2018, the Chilean government signed a deal with South Korea’s POSCO and electronics giant Samsung SDI to build EV battery-manufacturing plants in the country. In return, Chile will provide a guaranteed lithium supply at an agreed fixed price for 30 years. While it appears that Chile has not yet been able to deliver on the promised volumes, the policy intent is laudable.

Conclusion

In the SSA context, the energy transition should not just be about decarbonization for its own sake. Instead, it must be linked to addressing the energy access gap and encouraging productive uses of energy to create new competitive industrial clusters. If SSA’s economies are to develop, energy access and intensity need to improve drastically, and Africa should be allowed to use all its energy sources to achieve this. As Nigeria’s Vice President argued in a recent article, “a global transition away from carbon-based fuels must account for the economic differences between countries and allow for multiple pathways to net-zero emissions”.

About the Author

Dr Theophilus Acheampong is an economist and political risk analyst with over ten years’ experience working with governments, private investors and international organizations on natural resource governance and public financial management issues. He has worked as an independent consultant on various projects in the global energy industry, particularly in upstream oil and gas, and in providing economic analysis and market research focused on frontier emerging markets. He is currently co-editing a Palgrave MacMillan book titled “Petroleum Resource Management in Africa: Lessons from Ghana”, which examines the challenges and opportunities from ten years of oil and gas production in Ghana.