Summary

- Since 2006, Eurobonds have grown to become an important source of financing for development in various countries across the African continent.

- Policymakers have argued that the growing activity in issuing Eurobonds is a result of more easily available credit information.

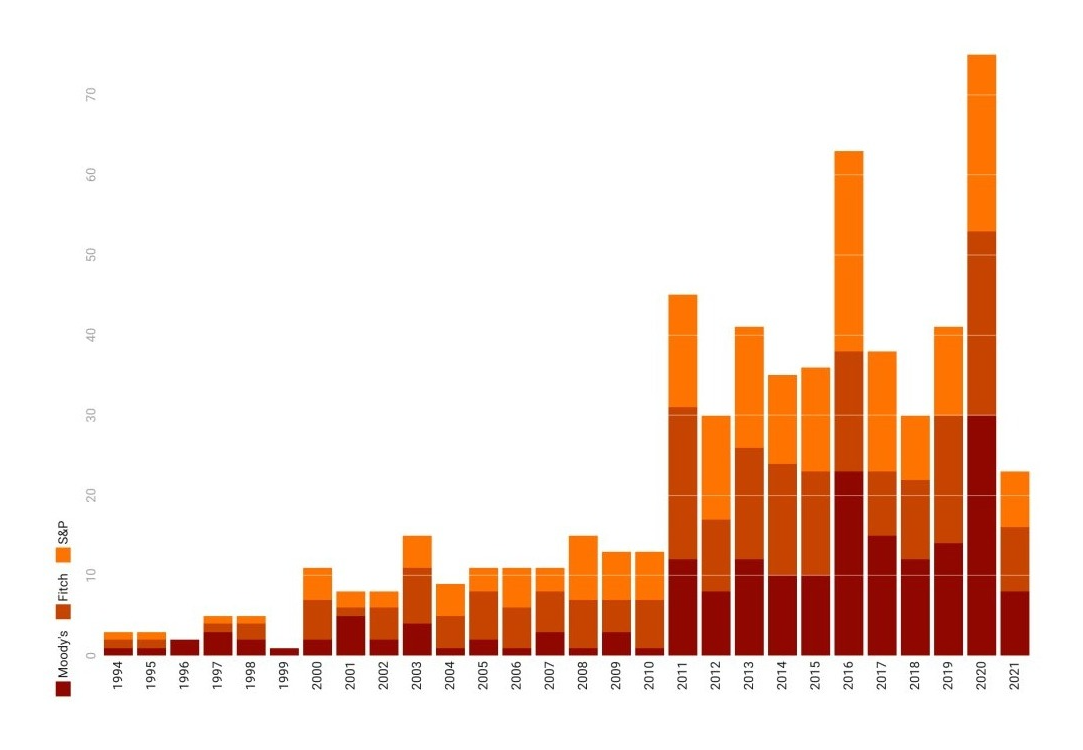

- In response to the increased activity in the Eurobond market, the frequency of assigning sovereign credit ratings in Africa has risen dramatically since the 2008 financial crisis.

- Compared to their first sovereign credit ratings, most African countries’ credit ratings have deteriorated, which has had serious implications on the cost of servicing debt.

Introduction

Over the past two decades, the number of African governments issuing Eurobonds for debt restructuring and infrastructure financing has increased. Drivers of this shift towards Eurobonds include the desire of African governments to rely less on aid resources to support development financing needs and the increased inclusion of African countries in global capital markets. Eurobonds are debt instruments denominated in a currency different from the home currency. Over the past 10 years, the tenures of the Eurobonds issued by African countries have ranged from 5 to 40 years. Since Eurobonds are issued on international financial markets, global investors require credit assessments of the issuer country. Therefore, sovereign credit ratings are a core requirement for issuing a Eurobond.

Sovereign credit ratings aim to assess a sovereign’s willingness to meet its financial obligations fully and on time. Thus, credit ratings have an impact on issuers as they determine the conditions under which governments can access debt markets. The growing activity in Eurobond issuance is said to be a result of more readily available credit information. The number of African countries rated by the three major rating agencies, Moody’s, Fitch, and Standard & Poor (S&P), increased to 31 in 2021 from only 10 in 2003. Meanwhile, the average number of annual credit ratings issued for countries across Africa rose from 7 between 1994 and 2007 to 37 between 2008 and 2020.

When it comes to credit ratings in the African context, common concerns include potential conflicts of interest, unreliable methodologies, and a lack of understanding of African economies. Furthermore, there are concerns surrounding the oligopolistic nature of the ‘big three’ rating agencies.

Various calls have emerged for a reform of the credit rating system. The UN Human Rights Office, for example, has criticized the “big three” rating agencies for their lack of accountability when issuing credit ratings, which in times of crisis can leave economies worse off. This issue became salient at the onset of COVID-19, when some countries were reluctant to sign up to debt restructuring initiatives for fear that they might be downgraded by credit ratings agencies.

The focus of this paper is to shed light on the drivers and outcomes of the growing activities in issuing Eurobond and sovereign credit ratings in Africa over the last decade. Our findings show that, compared to their first sovereign credit ratings, most African countries’ credit ratings have deteriorated, with serious implications for the cost of servicing debt. Based on these findings, we give recommendations on how the work of credit rating agencies within African countries can be improved.

The appeal of Eurobonds to finance development

African governments have used Eurobonds for deficit financing (including for increasing public infrastructure spending, mainly in energy and transport), benchmarking (including for expanding international market access for firms), and public debt management (including debt restructuring). The benefits of Eurobonds as a means to meet national financial demands has been promoted, among others, by credit rating agencies. For example, in an interview in 2013, S&P’s former senior director and author of ´The Growing Allure of Eurobonds for African Sovereigns’, Christian Esters, highlighted how African countries would benefit from issuing Eurobonds as they would be a reliable funding source away from donor support. African governments themselves have also looked towards relying less on aid resources to support development financing needs. Moreover, with the participation of African countries in debt relief initiatives such as the Heavily Indebted Poor Country (HIPC) debt relief program, general national debt outlooks have improved across the continent, facilitating access to international capital markets.

Furthermore, following the 2008 financial crisis which led to record-low interest rates in developed markets and meager returns in more established emerging markets, Eurobonds from African countries started to attract foreign investors. Eurobonds issued by countries formerly considered too risky to invest in became interesting for international investors. Investors’ appetites for yield thus allowed several African countries to issue US-Dollar denominated sovereign debt on a large scale. In addition, African Eurobonds were attractive to international investors as they were perceived as stable due to the positive growth trends of African economies. The positive macroeconomic outlook in particular was built on the high commodity prices in that period. The continued growth in African exports was expected to contribute towards increased foreign currency reserves, which would enable African governments to pay back their debt.

Although South Africa issued its first Eurobond as far back as 1995, the new Seychelles’ sovereign Eurobond issued in 2006 marked the entry point for many African countries into the international capital markets. Following a big increase in issuance since 2017, led by Egypt, Nigeria, and South Africa, the asset class has grown to 21 African countries with outstanding sovereign Eurobonds worth €123 billion. Eurobonds have thus grown to become a significant part of the debt burden of African countries. Even during the COVID-19 pandemic, $11.8 billion worth of Eurobonds was issued by African sovereigns in the first half of 2021.

Why do sovereign credit ratings matter?

Sovereign credit ratings aim to gauge the ability and willingness of any given sovereign to meet its financial obligations fully and on time. These ratings are a core requirement for issuing a Eurobond as they determine the conditions and the costs under which governments access capital markets. The government aiming to raise funds (issuer) through the Eurobond chooses underwriting syndicates to manage the bond issue. The underwriting syndicates usually consist of investment and merchant banks. Underwriting syndicates agree to pay their own money for the Eurobond, and then sell the bond to other merchant banks. Thus, when a country has a favorable sovereign credit rating and positive outlook, investment banks are more likely to issue Eurobonds on their behalf as the countries are more likely to attract investment.

Sovereign credit ratings are based on various economic, social, and political factors. Eight variables are relatively significant in determining sovereign ratings because they are repeatedly cited in the three international credit rating agencies’ reports: per capita income, gross domestic product growth, inflation, fiscal balance, external balance, external debt, economic development, and default history. An unfavorable change in these factors can lead to credit downgrading, which affects the price at which countries can borrow from international capital markets. As such, countries across the world prioritize maintaining and/or improving their sovereign credit ratings. Rating agencies’ environmental, social, and governance (ESG) scores are also becoming increasingly popular.

Credit ratings across African countries - more frequent, unsolicited and deteriorating

Collectively the three major rating agencies hold more than 95% of the global credit rating business, and their reach continues to grow; on the 2nd Feb. 2022, Moody’s announced it would acquire a majority shareholding in Global Credit Rating (GCR), a leading credit rating agency in Africa.

In the late 1990s, a handful of African countries acquired their first ratings. Most governments signed fee-paying and information-sharing agreements with the rating agencies, with annual fees levied either as a proportion of debt issuance volumes, or, in the case of large issuers, as mutually agreed lump sums. Through its credit rating initiative, the United Nations Development Programme played an important role in funding African countries credit rating processes in the early 2000s. Although many countries had received at least one sovereign credit rating by one of the “big three” rating agencies by 2007, the rating frequency did not rise significantly until after 2010 - i.e., shortly after the financial crisis (see graph below).

Figure 1: Increased frequency of sovereign credit ratings assignments - Total number of sovereign credit ratings assigned by Moody’s, S&P and Fitch.

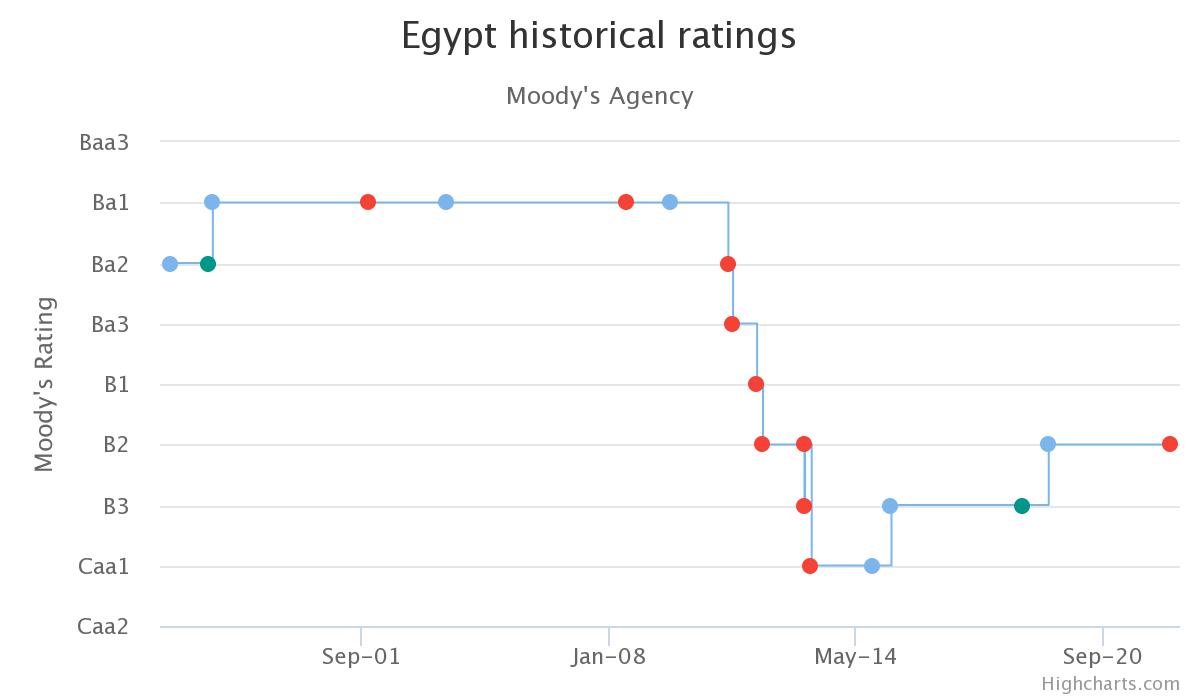

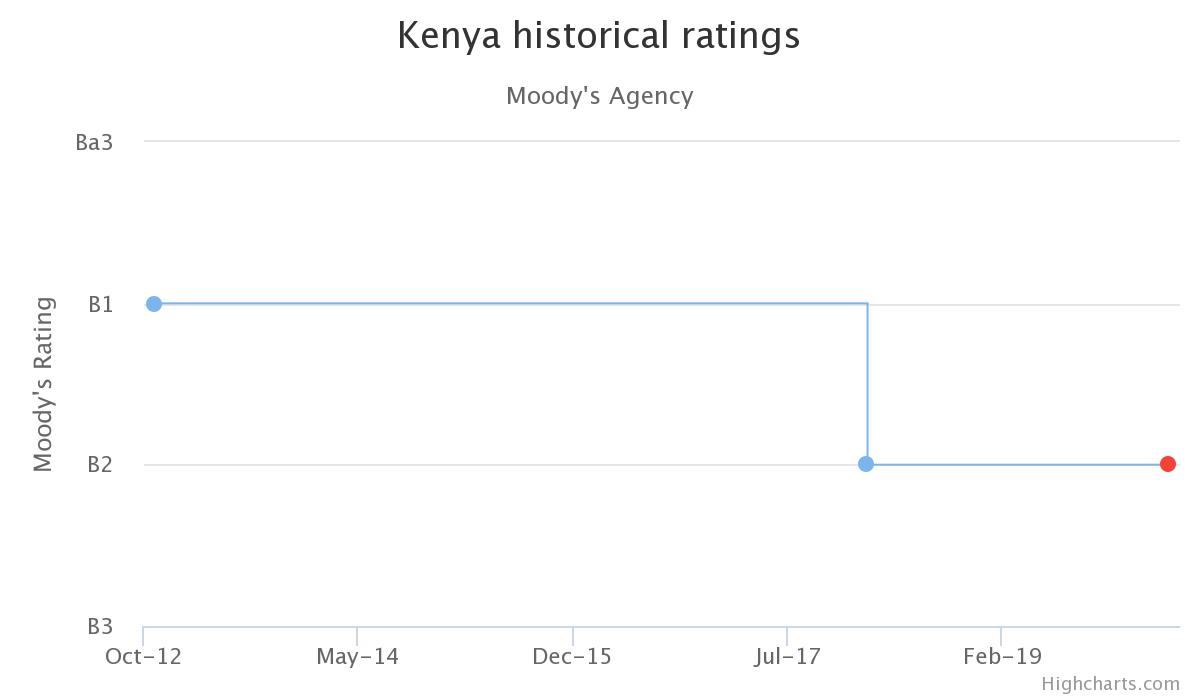

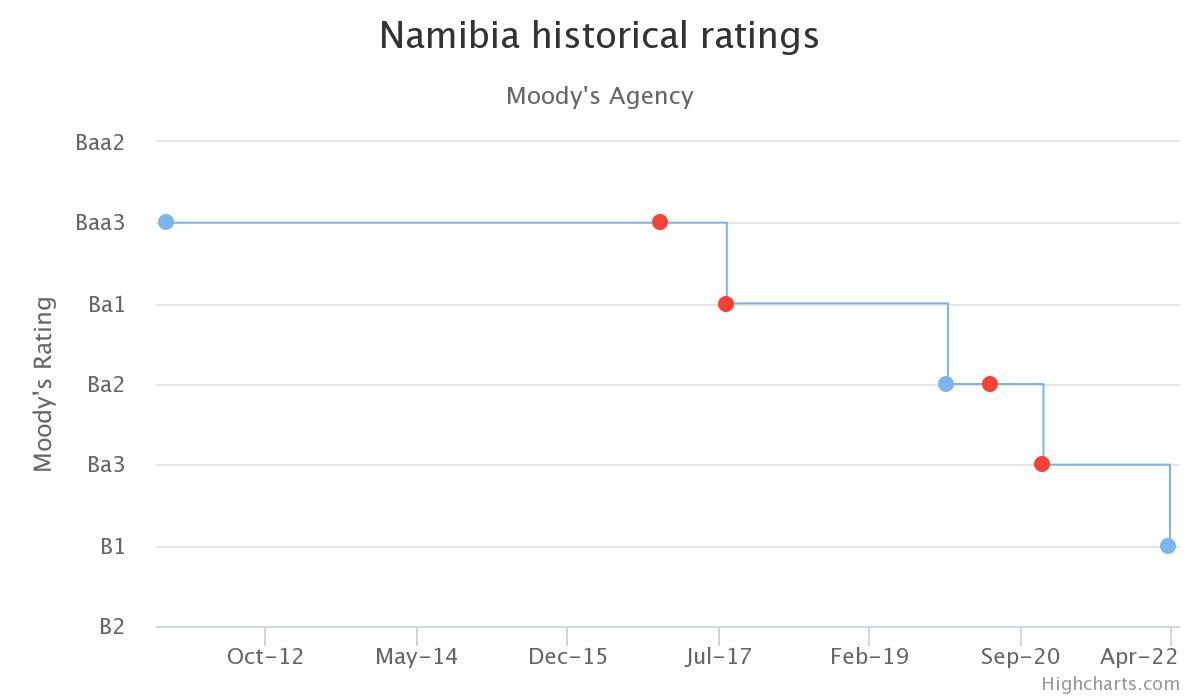

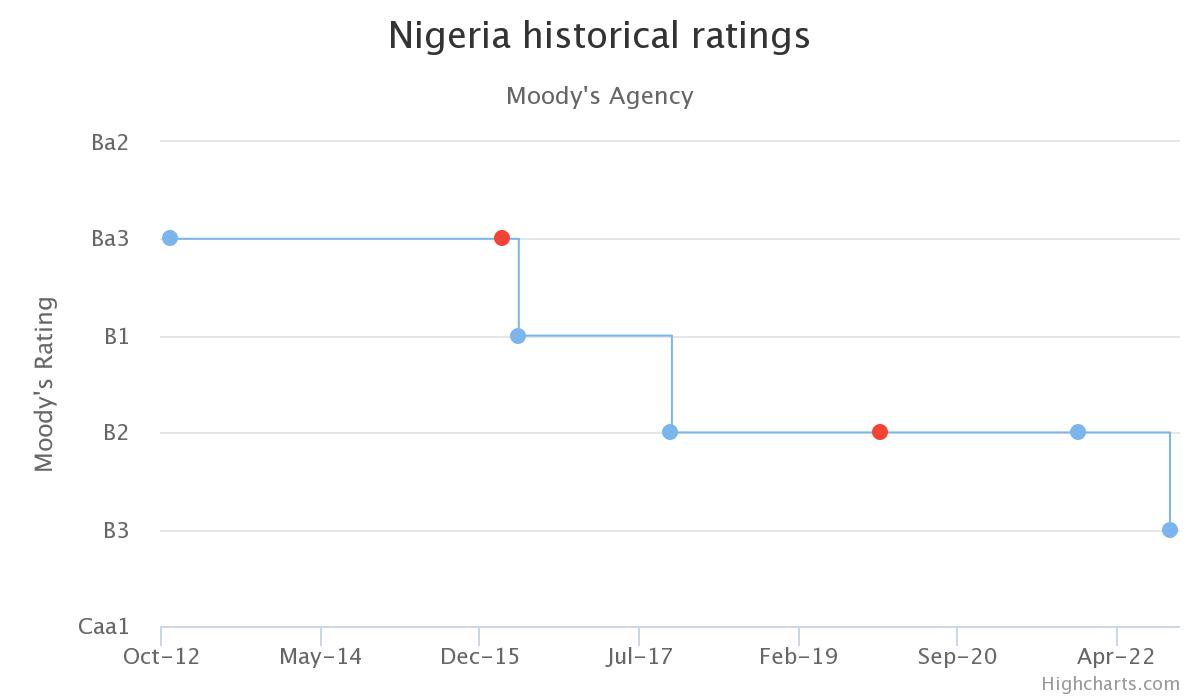

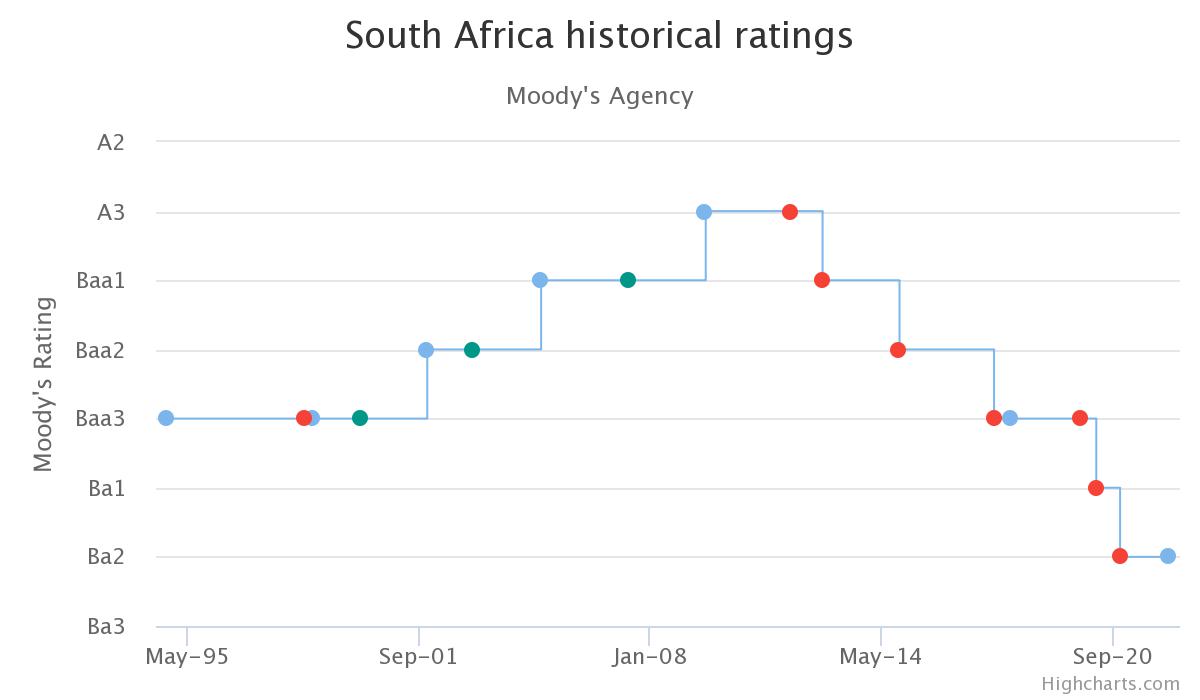

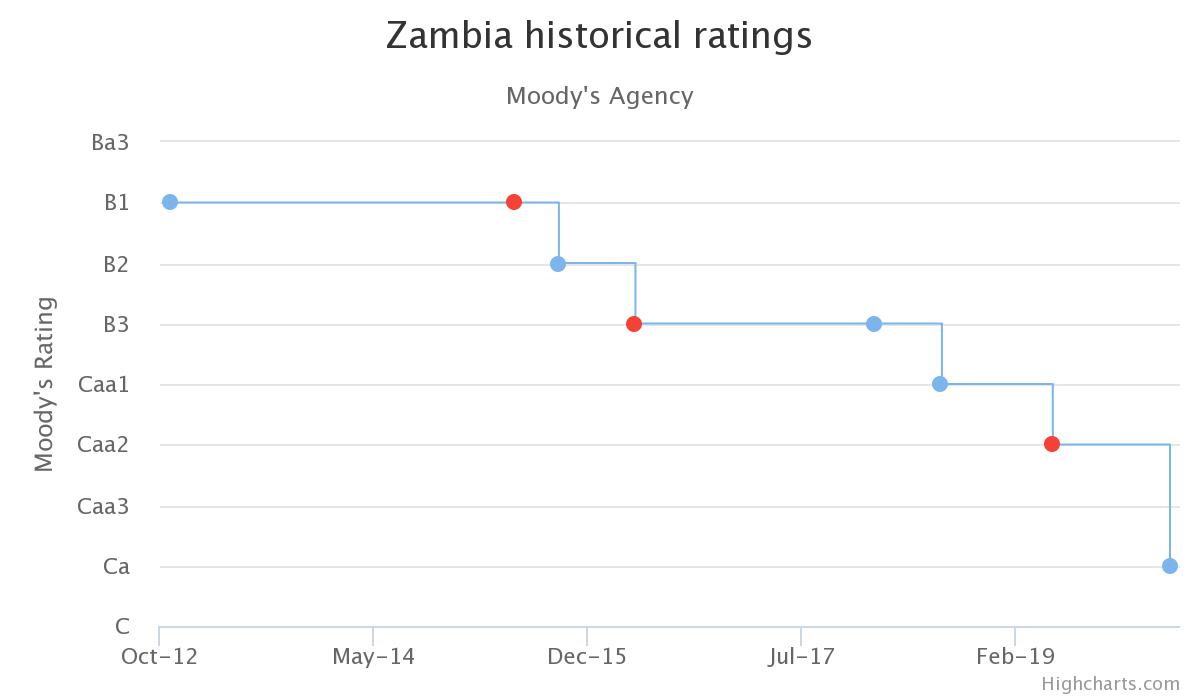

By September 2021, 32 African countries had received sovereign credit ratings from the ‘big three’, with countries such as Tanzania and Togo having only received a total of two ratings. Meanwhile Eurobond heavyweights, South Africa and Egypt, had received 57 and 64 credit ratings, respectively. Twenty African countries have received credit ratings from all ‘big three’ credit rating agencies, while 6 have received at least one credit rating from two of the ‘big three’ credit rating agencies. A trend visible from the sovereign credit ratings of most African countries, particularly those who have issued Eurobonds (as can be seen below), is that those countries’ current sovereign credit ratings are worse than their first credit ratings.

Figure 2 : Deteriorating sovereign credit ratings for Eurobond issuers - Egypt, Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa, Zambia, and Namibia

In the last decade, the ‘big three’ rating agencies were accused of assigning unsolicited credit ratings for various African governments including Ghana, Zambia, Namibia, Nigeria, and Tanzania. Unsolicited sovereign credit ratings are assigned without the issuer requesting the ratings. Thus, there is no formal contractual relationship between the rating country and rating agencies. In addition, these ratings also tend to not be paid for and are based on publicly available information. Of the three agencies, Moody’s has assigned the highest number of unsolicited ratings. Over the years, several African countries have contested these unsolicited ratings. At the beginning of this year, the Ghanaian government issued statements against its downgrade by Moody’s and Fitch.

Implications of downgrades - high interest rates and debt accumulation

Although rating agencies insist that their ratings are opinions and not recommendations to buy, sell, or hold a security, ratings have an impact on the conditions under which borrowers access debt markets. Poor credit ratings signal higher risk and tend to result in higher costs of borrowing from international capital markets. To date, the interest rates for borrowing from international financial markets are much higher for African countries than for economies in other regions of the world. Thus, for many African economies, interest repayments constitute the highest and fastest growing portion of expenditure with interest rates between 5% and 16% on 10-year government bonds, compared to near-zero to negative rates in Europe and USA. The high interest rates that African countries pay to borrow from international financial markets can be attributed partly to poor credit ratings but also to a mismatch between the instrument’s duration and what it is being used to fund, which may be long-term infrastructure projects. Overall, African countries have little control over their market borrowing costs.

Over the last decade, several African countries have witnessed credit rating downgrades. Even as they responded to COVID-19 challenges, countries such as Botswana, Mauritius, Nigeria, and South Africa were downgraded, causing a rise in bond interest. This rise meant that governments were required to pay more on the same amount of debt they owed. In addition, participation in relief programs, such as the Debt Service Suspension Initiative initiated at the onset of the pandemic, led to fears of credit ratings downgrades. Instead of doing what may have been best for the health of their populations or economic recovery from COVID-19, some governments prioritized debt repayments out of fear of being downgraded. This priority was achieved through tight macroeconomic policies, which tend to be counterproductive for long-term investment and growth and have a negative effect on debt crisis prevention and resolution. When governments are downgraded or fear being downgraded, their capacity to respect, protect, and fulfill human rights obligations can be enormously impacted.

What can be done?

Common concerns when it comes to credit ratings in the African context include potential conflicts of interest, unreliable methodologies, and a lack of understanding of African economies. Furthermore, there are concerns surrounding the oligopolistic nature of the ‘big three’ rating agencies. Below we discuss some ways in which the work of credit rating agencies within African countries could be improved.

Adopt appropriate methodology and prioritize local knowledge

Credit ratings tend to rely on past behavior, which means that some African countries are at a disadvantage if they have not been receiving credit from international capital markets for a long time. Another consideration taken for sovereign credit ratings is an assessment of the future. However, a lack of understanding of the environment coupled with differences in culture or language between the country where the ratings agency is based or where the analysts are from and the African countries also creates room for error. A key question of whether credit ratings are representative of associated political and country-specific risks has arisen in the past due to the immense influence of credit rating agencies coupled with their limited presence on the African continent. S&P, for instance, only has one office on the African continent, in Johannesburg. Moody’s also only has one office in Johannesburg, which covers all the 28 countries to which it assigns ratings. Fitch has no offices in Africa. For credit ratings to appropriately bridge the information gap, the agencies must invest more in understanding the specific present contexts of the countries they are rating.

Limit unsolicited credit ratings

In addition to having analysts present in countries and familiar with the domestic context, rating agencies must also adequately consult with government representatives during the review process. The potential conflict of interest arises when there is a difference of treatment depending on whether issuers pay the credit rating agencies for the ratings or the ratings are unsolicited. When ratings are unsolicited, missing information impedes objective ratings regarding a country’s economic situation and outlook. Thus, rating agencies should be cautious when issuing such ratings. If the rating agencies are unable to get the necessary information from governments, an alternative option would be to employ the African Peer Review Mechanism, an African Union initiative enabling countries to monitor governance performance, before changing a sovereign credit rating.

Independent collection of financial data and stricter regulation of credit rating agencies

Rating agencies have been criticized by the UN Human Rights Office for their lack of accountability when issuing credit ratings, alongside leaving economies worse off. Therefore, it is imperative that the work of rating agencies be regulated through holding them accountable (for example, through issuing fines) if they do not exercise due diligence when assigning credit ratings.

For many African economies, interest repayments constitute the highest and fastest growing portion of expenditure. Thus, to ensure that interest rates reflect the risks of lending to a country, it is also important to have insights into how well public funds in a country are spent. This insight can be gained through ensuring that borrowing of Eurobonds is attached to specific projects so that it is transparent what the funds will be used for. The African Union, for example, could make this a recommendation for all African countries intending to issue Eurobonds. States could submit data to the African Union, which would then track the progress of projects and repayments of debt. Such a collection of data would make restructuring agreements between creditors and lenders possible. If credit ratings do not reflect the work on the ground, the rating agencies could be held to account.

And finally, understanding what countries are borrowing for is vital. If countries continue to issue Eurobonds so that they can repay past debt, rather than for development projects, debt restructuring should take place rather than increased borrowing.

About the Authors

Nora Chirikure is a research assistant at Africa Policy Research Institute (APRI). Nora holds a B.Sc. in Politics, Philosophy and Economics from the Erasmus University in Rotterdam. She is currently pursuing a M.Sc. in Economics and Management Science at the Humboldt University in Berlin.

Dr. Olumide Abimbola is Executive Director of APRI - Africa Policy Research Institute, a Berlin-based think tank. He previously worked on trade and regional integration at the African Development Bank, and on natural resources governance at the GIZ.

Dr. Grieve Chelwa

Dr. Grieve Chelwa is the director of research at the Institute on Race, Power and Political Economy at The New School. Prior to joining the Institute, Dr. Chelwa was a Senior Lecturer at the Graduate School of Business at the University of Cape Town. He has previously held postdoctoral fellowships at Harvard University and the University of the Witwatersrand. Dr. Chelwa is a frequent commentator on current events and his opinions have appeared in the New York Times, Washington Post, BBC, NPR and Bloomberg among others. He tweets at @gchelwa.