Summary

- On December 7, 2024, voters in Ghana will head to the polls to elect a new president and 276 legislators, the ninth such election since the West African nation transitioned to democratic rule in January 1993.

- While the Electoral Commission has qualified 12 candidates to be on the presidential ballot, in reality the election is a race between the candidates of the country’s two rival parties, the National Democratic Congress (NDC) and the New Patriotic Party (NPP).

- The December elections are being held against a backdrop of deepening polarisation and a harsh economic environment triggered by the country’s first-ever sovereign debt default. Responsibility for the state of the economy, unemployment and ecocide are among the key issues dominating the campaigns.

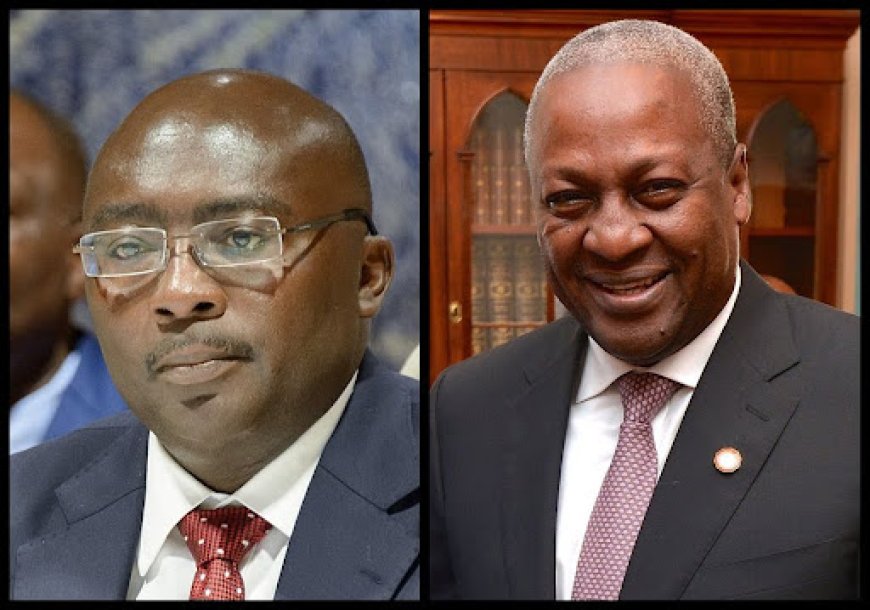

- Incumbent President Nana Akufo-Addo of the NPP is term-limited. His party, now led by Vice President Bawumia, is campaigning to win an unprecedented third term in government, while the NDC, led by former president Mahama, is determined to return to power and avoid becoming the first party to stay in opposition three elections in a row—an outcome that could have existential consequences for the NDC in Ghana’s winner-takes-all political system.

- Judging from the tone of the campaigns and the divergence between the two parties’ trust in the electoral commission, the judiciary and other state institutions involved in assuring election integrity, there is widespread apprehension that this year’s elections could turn disorderly.

- Given Ghana’s increasingly chilly relations with the military junta in Burkina Faso and the existence of multiple, politically exploitable internal conflicts, an election gone bad could destabilise the country and worsen the regional security situation.

The electoral system and election management

On December 7, 2024, voters in Ghana will head to the polls to elect a new president and 276 members of parliament. The December general elections will be the ninth such election since the West African nation transitioned to democratic rule in January 1993. Occurring against the backdrop of deepening partisan polarisation, an unprecedented sovereign debt default and an accompanying economic crisis, these elections will test the resilience of Ghana’s democratic project and the country’s reputation as an oasis of stability and peace in a politically turbulent neighbourhood.

Ghanaian elections have always been a fraught affair, a reflection of the intensity of the rivalry between the country’s two main political parties. In the elections held in late 1992 to usher in Ghana’s current Fourth Republic, the NPP boycotted the December parliamentary elections en masse after rejecting the results of the preceding November presidential elections, won by the NDC’s Jerry John Rawlings, as a ‘stolen verdict’. Of the last eight general elections, three (2000, 2008, 2016) produced a party turnover in government and two (2012, 2020) gave rise to a presidential election petition before the Supreme Court, which was settled, in each case, in favour of the originally declared winner. In all instances, transfer of power has been peaceful and orderly. Coupled with the fact that the constitution’s two-term limit on presidential tenure enjoys both popular and cross-party support and has been honoured routinely without controversy, this tradition of peaceful transfer of power underscores the country’s reputation as a democracy exemplar in the region and across Africa.

Ghana holds its presidential and parliamentary elections once every four years, following a timetable specified in the country’s 1992 Constitution. While not constitutionally mandatory, both presidential and parliamentary elections have been held on the same day since the December 1996 elections. All citizens aged 18 and above are eligible to register to vote. Out of a population of roughly 35 million (2024 est.), 18,774,159 are registered to vote in the upcoming December 7 elections. Historically, voter turnout in Ghana’s elections has been high, with a turnout of 79% recorded in the December 2020 general elections. For the 2024 elections, the country has been divided into 276 single-member constituencies, each of which is further divided into several polling stations where voting takes place in-person on election day. Voting in the December 7 elections will take place at 40,975 polling stations across the country, including 328 special voting centres.

Members of parliament are elected on a first-past-the-post basis. Thus, the candidate who obtains the most votes among the contestants on a constituency’s parliamentary ballot wins the seat. However, to win the presidential election, a candidate must obtain at least a simple majority of the valid votes cast. Where no candidate on the presidential ballot is able to obtain a majority of the votes in the initial round of voting, a run-off election between the two candidates with the highest number of votes must be held within twenty-one days of the first election to decide the winner.

The contest and contestants

The organisation, conduct and management of all aspects of the elections, including registration of voters, qualification of parties and candidates, printing of ballot papers, counting of votes, and declaration of results, are entrusted to the Electoral Commission (EC), a body established under the constitution and ‘not subject to the control or direction of any person or authority’ in the performance of its functions. The chairperson of the commission and her two deputies, who, together, comprise the executive body of the commission, are each appointed by the President of the Republic upon the occurrence of a vacancy on the commission. They hold office until they reach a mandatory retiring age that is the same as that of the country’s senior judges. The chair and deputy commissioners of the EC may be removed by the President only for stated reasons and in accordance with a quasi-judicial ‘impeachment’ process that is triggered by a petition to the President and overseen by the chief justice. The current chairperson of the EC and her two deputies were appointed by President Akufo-Addo in 2018, following the impeachment and removal of the previous commissioners on charges of violating procurement laws.

The EC has qualified 12 candidates to be on the presidential ballot for the December 7 elections. This number comprises eight political party candidates and four independents. However, as in previous elections, the presidential election is expected to be a two-horse race between the candidates of the NPP and NDC. Far fewer candidates are competing for parliament in each of the 276 constituencies, with the NPP and NDC being the only parties fielding candidates on the parliamentary ballot in all 276 constituencies.

The NPP candidate for the 2024 presidential elections is Dr. Mahamudu Bawumia, 61, the current two-term vice president to President Akufo-Addo. A former deputy governor of the central bank, Bawumia was considered a political outsider when he was first picked by Akufo-Addo as his running mate on the NPP ticket for the 2008 presidential elections. After losing both the 2008 and 2012 presidential elections to the NDC, the pair eventually won the 2016 elections and was re-elected in 2020. An economist by training, Bawumia has played the role of head of the Akufo-Addo administration’s economic management team since 2017—a role conventionally reserved for Ghana’s vice presidents. He emerged as the party’s 2024 presidential candidate after a divisive internal primaries campaign, which ended with one of the main contestants, former trade minister Alan Kyerematen, resigning from the party and launching an independent bid for the presidency.

Bawumia is the first Muslim to be selected as the presidential candidate of a major political party in Ghana. He is also the first NPP presidential candidate to come from outside the party’s Twi-Akan ethno-linguistic base. Bawumia has chosen Dr. Matthew Opoku Prempeh, 56, as his running mate. Prior to his selection as vice presidential candidate, Prempeh was minister of energy in the Akufo-Addo administration (and formerly minister of education) and a member of parliament for one of the NPP's strongholds in Kumasi, the party's traditional home. A Christian and an Asante (Akan) from an influential NPP political family, Prempeh's choice gives the NPP ticket the ethno-regional and religious balance considered politically obligatory in a country that is predominantly Christian (71%) and Akan (46%).

The NPP’s election strategy hinges on holding and deepening its electoral dominance in the vote-rich Ashanti and Eastern regions and using Bawumia’s candidacy to halt, and possibly reverse, the NDC’s traditional dominance in the North as well as the Muslim-populated ‘zongo’ communities in the rest of the country. Besides aiming for a higher-than-usual turnout in the NPP’s strongholds, the Bawumia campaign is also counting on the popularity of its ‘Free SHS’ (Senor High School) policy to give it an electoral advantage among young, first-time voters and non-middle-class parents with high-school-age children.

For the fourth time in a row, the NDC's presidential candidate is John Dramani Mahama, 65. A former vice president (2009-2012), Mahama served the remainder of the uncompleted term of the late President John Atta Mills, following Mills’ death in office in July 2012. He was subsequently elected to his own four-year term as president in 2013 after defeating Akufo-Addo (NPP) in their first direct face-off. Mahama lost his bid for re-election to Akufo-Addo in 2016, becoming the only Ghanaian president thus far to suffer defeat after one term in office. He contested and lost again to Akufo-Addo in 2020. His retention by the NDC as its presidential candidate for the December 2024 elections sets up the first presidential contest in which both candidates of the two major parties are from the historically marginalised North. For the second time, Mahama has chosen as his running mate the retired academic and his former minister for education, Professor Jane Naana Opoku-Agyemang, 72. As in the 2020 elections, the pairing of Mahama with Opoku-Agyemang, who is from the coastal Akan Fante region, gives the all-Christian NDC ticket both gender and ethno-regional balance.

The NDC campaign seeks to maximise the party’s vote harvest in its traditional non-Akan strongholds while outperforming the NPP in the North and the coastal Akan communities of the Central and Western Regions. Winning the coastal (non-Twi) Akan vote has been indispensable to NDC’s electoral victory in past general elections. In addition, the party is counting on dissatisfaction with the state of the economy to give it an electoral advantage among urban voters, particularly the youth.

Although the 2024 race is essentially between Mahama and Bawumia, at least two other candidates on the 12-person presidential ballot may be considered politically significant in this year's elections. Notably, NPP defector Alan Kyerematen's independent candidacy could frustrate the NPP's plans to outperform its historically strong showing in its electorally indispensable Kumasi stronghold, which is also Kyerematen’s home-base and where he has a loyal following, most of whom are also NPP defectors. Another independent candidate of note is Nana Kwame Bediako, 44. A real estate entrepreneur, Bediako projects himself as the candidate for a new generation and has targeted the disenchanted urban youth vote with an eclectic message of hope and prosperity and a pan-African renaissance. While neither Kyerematen nor Bediako poses a threat to the NPP-NDC duopoly, the combined effect of their candidacies, particularly in the face of youth disillusionment with the two establishment parties, could push the two-horse race into a second round of voting. To tap into the growing disenchantment with the two main parties, both Kyeremanten and Bediako are playing up their no-party, independent candidacies. As both are also Twi-Akan, it is expected that their individual and aggregate vote tallies in the presidential elections would come largely at the expense of the NPP’s candidate.

The acerbic tone of the campaigning by the NPP and NDC, coupled with a sharply partisan divide on the trustworthiness and impartiality of the key state election integrity institutions, notably the EC and the judiciary, is fuelling apprehensions that the December elections could turn exceptionally disorderly. While similar anxieties and episodes of violence have blighted recent Ghanaian elections, the NDC’s announced intention to boycott the courts should the presidential elections go against it, citing suspected partisan bias on the part of the Supreme Court and the EC, as well as hawkish statements by NPP leaders that the party has no plans to hand over power to its arch-rivals, have heightened tensions.

The issues

The economy dominates this year’s Ghanaian elections. The country is in arguably its worst economic crisis since the return to democratic rule. For the first time in its history, Ghana defaulted on its USD 30 billion sovereign debt in 2022, throwing the economy into a tailspin, as inflation shot past 50% and the cedi depreciated dramatically against the dollar. The government, which had earlier sworn not to return to the IMF, was forced to make an about-face and turned to the IMF for a USD 3 billion bailout. As part of the bailout conditions, the government implemented a debt restructuring that imposed an unprecedented ‘hair cut’ on local bondholders, triggering protests from pensioners. While inflation has since slowed to a little above 20%, the cost of living continues to bite.

In the latest Afrobarometer survey, 4 out of 10 Ghanaians identified unemployment as the ‘most important problem facing the country that the government should address’, with 1 out of 4 and 1 out of 5, respectively, identifying management of the economy and increasing cost of living among their topmost concerns. Overall, 8 out of 10 Ghanaians believe the country is ‘going in the wrong direction’, with only 15% feeling positive in this regard. At the height of the economic crisis in 2022, nearly 9 out of 10 Ghanaians felt the country’s economic situation was either fairly or very bad. While that number has dipped somewhat, roughly 8 out of 10 Ghanaians still feel the economic situation is fairly or very bad, with roughly 7 out of 10 Ghanaians feeling the country’s economic condition has worsened in the last 12 months. The percentage of Ghanaians who say they are ‘fairly or very satisfied’ with the way democracy is working in the country has declined by 29 points since 2017.

Seizing on the harsh economic conditions and NPP’s self-branding as the party of business and competent economic management, Mahama and the NDC have made the December 7 elections a referendum on the eight years of the Akufo-Addo-Bawumia administration. Mahama’s campaign has blamed the sharp economic downturn on incompetent management of the economy and reckless borrowing by the Akufo-Addo administration, singling out Bawumia for blame on account of his background as an economist and his role in the Akufo-Addo government as head of the economic management team. With virtually all key economic indicators far worse now than they were at the time of the 2016 campaign, when Mahama was president, utterances about the economy and economic management made by Bawumia and Akufo-Addo during the 2016 and 2020 campaigns have been resurrected and turned against the NPP by their rivals.

On their part, Bawumia and the NPP have blamed the current economic crisis, including the sharp depreciation of the cedi, on a combination of the COVID-19 pandemic, the knock-on effects of the Russian invasion of Ukraine and a rise in global interest rates. The Bawumia campaign has also tried to distance their candidate from the economic record of the Akufo-Addo administration, arguing that as vice president he was not necessarily in the driver's seat and that, notwithstanding his designation as head of the government’s economic management team, as vice president he was not even as powerful in matters of economic policy as the finance minister. If elected, Bawumia has promised a new economic direction, including the cancellation of certain unpopular taxes introduced by the Akufo-Addo government. He has also positioned himself as the candidate for the future by promoting digitalisation initiatives and policies as a way to jump-start the economy.

The NPP has also sought to deflect attention from the economy by touting fulfillment of the party’s signature 2016 campaign promise of universal ‘Free Senior High School’ (FSHS) education as a game-changer and proof of the party’s credibility. In the latest Afrobarometer survey, roughly 9 out of 10 Ghanaians expressed support for the FSHS policy to be continued by the next government. To minimise electoral disadvantage from the FSHS programme, the NDC has promised to continue and ‘improve’—abandoning its earlier promise to ‘review’—the FSHS programme and make it more fiscally sustainable, a pledge the NPP has dismissed as insincere, reminding voters of the NDC’s 2016 stance in support of ‘progressively free’ SHS and corresponding rejection of universal and instant ‘free SHS’ as infeasible. The NPP has also pointed to the number of ongoing and completed infrastructure projects, notably in the road sector and the construction of new health care facilities under its ‘Agenda 111’ programme.

Other issues that have received significant airtime during the campaign season are corruption and illegal artisanal gold mining, known as ‘galamsey’. Mahama, who was unable to shake off accusations of personal corruption during the 2016 campaign, has turned the tables on the NPP, citing the many high-profile corruption scandals and widespread accusations of ‘state capture’ and nepotism to paint Akufo-Addo as presiding over a corrupt government. On galamsey, while the problem is a perennial one, the menace appears to have grown in scale under the NPP’s watch, with devastating impacts on the environment and ecology, including critical water bodies that serve communities across the country. This has put the NPP on the defensive. Government inertia in dealing with the crisis has led to public outcry and protests and fuelled allegations of party complicity in the activity.

In the face of the government’s current debt sustainability and fiscal crisis, both the NPP and NDC have been noticeably silent on how each proposes to fund their growing list of new campaign and manifesto promises, including promises to cut unpopular taxes, or what measures they would take to address the drivers of the country’s recurring economic difficulties. There is widespread scepticism about the parties' ability to make good on their promises and growing concern that the country’s debt and fiscal crises will persist.

Concerns about election integrity and peace

Ghana’s quadrennial general elections have always been a hotly contested and tense affair between the NPP and NDC, going back to the 1992 elections, the parliamentary half of which the NPP boycotted following allegations that the NDC had stolen the preceding presidential elections. The winner-takes-all character of Ghanaian politics, in which the party that wins control of government gets to monopolise all power and associated opportunities, including public jobs and contracts, has helped to sustain this intense partisan rivalry. This has sometimes led to election violence, such as during the 2020 elections when eight fatalities were recorded. In 2019, a new law outlawing party-associated ‘vigilantes’ notorious for fomenting violence and imposing enhanced criminal penalties on violators was passed with bipartisan support. Despite this, there are widespread fears and indications that the December 7 elections pose an exceptional risk of violence and disorder. A number of factors account for this dismal assessment.

Both parties have approached the upcoming elections as a ‘do-or-die’ affair. The NPP, signalling its determination to break the eight-year jinx and hold on to power for an unprecedented third term, has campaigned vigorously, exuding a degree of confidence about its electoral prospects that appear to unnerve its rivals and confound sections of the public. Hawkish utterances on the campaign trail by influential NPP leaders, including President Akufo-Addo himself, have suggested that it would be irresponsible on the NPP’s part to allow the NDC back into power. These claims have been interpreted by the NDC as a warning that the NPP is planning to rig the elections. On its part, the NDC, similarly determined to avoid remaining in opposition for three consecutive terms, is convinced that the objective conditions, in particular the dismal state of the economy and widespread despondency over the direction of the country, point to certain NPP defeat in the December 7 elections.

Reports by the Economic Intelligence Unit (EIU) and Fitch predicting victory for the NDC in the 2024 elections are consistent with similar survey findings by Global InfoAnalytics, a local pollster widely perceived as NDC-friendly. This has bolstered the NDC’s belief that it is on course to win the elections. The NPP has recently countered with a survey by a party-aligned pollster showing the ruling party ahead in both the parliamentary and presidential elections, with the possibility of a presidential run-off. The NDC appears unwilling to countenance the possibility of an NPP victory, believing that such an outcome is possible only through electoral malpractice. The belief by each of the two parties that they must win the December 2024 elections or else has heightened mutual antagonism and tensions going into the elections. Mahama’s open pledge to pursue and prosecute unnamed NPP officeholders and partisans for unspecified corruption has further sharpened the bitter rivalry between the two.

Compounding anxieties about the upcoming elections is the fact that, according to the latest Afrobarometer survey data, the key state institutions responsible for ensuring or safeguarding the integrity of Ghana’s elections and its outcomes suffer from exceptionally low public trust. Only about 3 in 10 Ghanaians say they trust the EC or the police, while roughly 35% say they trust the courts. The armed forces, which are usually on standby during elections and may be deployed should the security situation overwhelm the police, are alone among state institutions in enjoying the trust of roughly 7 out of 10 Ghanaians. Survey data aside, the actions, reactions and utterances of the NDC and NPP leaders and partisans point to sharp division between the parties in their trust for the EC, the Supreme Court and the security agencies.

The NDC’s relations with the current EC have been chilly since the last Mahama-appointed chair and members of the Commission were removed and replaced by appointees of Akufo-Addo in 2018. While the leadership changes at the EC followed due constitutional process, the NDC has maintained that the changes were politically motivated and done in bad faith to enable the NPP to appoint a party-friendly or pliable commission. Since then, the NDC and the EC have clashed over a number of election-related issues, a situation that is not helped by the fact that the NPP almost habitually and openly sides with the EC in these disputes. In the lead up to the December 7 elections, the NDC has raised questions about the integrity of the electoral register, calling for an independent audit of the register, a demand both the EC and NPP have dismissed as a red herring.

Mahama and the NDC have also accused the Akufo-Addo administration of packing the Supreme Court in anticipation of a disputed election. Currently, only two judges on the 15-judge court were appointed by a president other than Akufo-Addo. This, together with the fact that the outcomes of a number of high-profile, politically charged cases handled by the Supreme Court have been unfavourable to the NDC and its interests, has fuelled NDC accusations of anti-NDC hostility on the part of the court and, in particular, the chief justice, who selects which panel of judges gets to hear which cases.

Similar accusations of partisan bias have been made against the security agencies, particularly following the leak of an audio tape on which certain blatantly partisan senior police officers are heard raising doubts about the reliability of the country’s inspector general of police (IGP) and urging his removal in advance of the elections. The subsequent designation by the President of a deputy police chief with specific command of ‘operations’ was interpreted by some as a pre-emptive sidelining of the IGP in election security operations.

Mahama and the NDC have stated publicly that, if the results of the December 7 presidential elections were to be declared in favour of Bawumia, they would not turn to the courts to register their rejection of the results. The NDC had also indicated that it would sign a “peace pact” brokered by the National Peace Council, pointing out that, notwithstanding a similar peace pact in 2020, no arrest was ever made in connection with the killings of eight persons in a single constituency during the 2020 elections. However, on November 28, Mahama joined the NPP’s Bawumia and other presidential candidates to sign the “presidential elections peace pact.” Signatories to past pre-election peace pacts have committed to use established constitutional and other legal processes to resolve any disputes arising out of the election. It is not clear whether the NDC’s signing of the 2024 peace pact reverses the party’s preemptive boycott of the Supreme Court in the event of a disputed election.

Disinformation and misinformation by partisans of the NPP and NDC, both on the campaign trail and in the traditional and social media, have grown exponentially in the lead up to the December elections. This has been aided by Ghana’s generally unregulated landscape for the media and election campaigns. In one egregious case, a presenter on a radio station owned by a leading executive of the ruling party deliberately misinformed his local language audience that voters intending to vote for the main opposition candidate and others placed lower on the ballot would cast their vote on a day after December 7, stating that the official December 7 election date was reserved for voters intending to vote for the candidate of the NPP and others placed on the first half of the ballot paper. The offensive broadcast was subsequently removed from the station’s social media channel following the arrest of the offender for ‘publication of false news’.

A surprise book launch of a Russian language edition of Mahama’s 2012 memoir, held in July 2024 at the Institute of Social Sciences in Moscow, where Mahama had been a graduate student in the 1980s, and with Mahama and some NDC figures in attendance, sparked rumours, amplified by NPP-affiliated media, that the NDC candidate was flirting with the Russians, a claim the NDC angrily dismissed. Mahama’s lawyers have recently threatened an NPP-friendly newspaper with a defamation lawsuit if the publishers of the newspaper failed to retract a story alleging a deal between Mahama and certain Russian oligarchs for assistance in connection with the upcoming elections. Mahama has demanded that the newspaper publish the retraction, along with an “unqualified apology”, within a specified number of days before the December 7 elections.

Other wild cards associated with Ghana’s election this year add to the anxieties and uncertainties surrounding its outcome or immediate aftermath. Notably, this is the first election in which both presidential candidates of the two main rival parties hail from Ghana’s North, roughly comprising the five northernmost regions of the country. Historically and spatially the poorest region of the country, the North is also the site of intractable and volatile communal conflicts that tend to be exploited politically and thus assume a binary partisan character, particularly during elections. The Mahama-Bawumia contest could further polarise communities in the North, reigniting local conflicts and raising the prospect of election-day and post-election violence. Already, the township of Bawku and its immediate environs, near the border with Burkina Faso and home to a longstanding communal conflict, is experiencing a flare-up of violence that appears to have assumed a partisan character. It is also unclear what impact, if any, the independent candidacy of NPP defector Kyerematen might have on the security situation in his home base and the NPP’s stronghold of Kumasi on election day and in its aftermath.

Underscoring widespread concern about likely election-related disorder or conflict, the US State Department recently announced a ‘visa restriction policy’ to take effect ‘in advance of’ the December 7 elections, targeting ‘individuals believed to be responsible for, or complicit in, undermining democracy in Ghana’, including through manipulation or rigging of the electoral process and the use of violence to intimidate, coerce or prevent people from exercising their rights. Interest in the upcoming elections has been generally high among Ghana’s international partners, including the EU, which, in the past, has joined other regional and international actors like ECOWAS and the Commonwealth, and has sent election observation missions to observe Ghana’s elections. The Coalition of Domestic Election Observers (CODEO), a broad-based network comprising 42 Ghanaian civil society groups, including faith-based groups, trade unions and business and professional associations, has trained and deployed EC-accredited citizen observers in every election since 2000. Since 2008, the CODEO has also used parallel vote tabulation (PVT) to monitor election-day returns. It is expected to deploy some 4000 observers across the country on election day.

Regional and international implications

A peaceful outcome in Ghana’s December 7 elections is not expected to change the nature or direction of the country’s foreign policy or international relations in any significant way. Although the two parties describe themselves as ideological opposites, the NPP being the conservative, centre-right party and the NDC the social democratic, centre-left party, in substance there is little policy distance between them. Notably, electoral turnover from one party to the other has not produced a discernible shift in the government’s relations with international or relation actors. However, should the December 7 elections go badly, there is a risk that the parties would regionalise or internationalise any ensuing conflict, as each party tries to draw different regional or international interests and actors to its side.

Ghana sits in a troubled and volatile neighbourhood, where military juntas that have recently overthrown democratic governments in Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger over security-related concerns continue to face extremist and jihadist threats to both their regime security and their national territorial integrity. The fragile security situation in the region has recently assumed international, geopolitical dimensions, as the three beleaguered Sahelian regimes have broken ties with both ECOWAS and their countries’ longstanding UN and European partners, turning instead to Russia for military assistance. Given this complicated security situation, coupled with the country’s frosty relations with the military junta in Burkina Faso over the presence of Russian military resources in the region, a disorderly election outcome in Ghana could have wider regional security ramifications, particularly if it was protracted, led to a breakdown of civilian control or spread to the country’s border communities. Beyond that, such a crisis would represent a severe reversal not only for Ghana and its stable democratic project but for the fortunes of democracy in West Africa as a whole.

Given the relatively high stakes, Ghana’s regional and international partners must make their best effort to work with the country’s political leaders, state institutions and civil society to assure the integrity of the December 7 elections and their outcome. Beyond the 2024 elections, Ghana must examine the constitutional, legislative and institutional frameworks that govern the country’s politics, elections and electioneering and make appropriate reforms to fix structural gaps and weaknesses. Included in these reforms must be the president’s overweening appointment powers and the unregulated length and conduct of election campaigns, both of which fuel polarisation and keep the country on edge during its quadrennial elections.

About the author

H. Kwasi Prempeh

H. Kwasi Prempeh is the Executive Director of Ghana Center for Democratic Development (CDD-Ghana) and Project Director for the West Africa Democracy Solidarity Network (WADEMOS). He is currently a Richard von Weizsacker Fellow at the Robert Bosch Academy in Berlin.