Foreword

The 16th BRICS Summit took place on 22-24 October in Kazan, Russia, with new members Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, and the United Arab Emirates participating for the first time. As BRICS expands its influence and membership, particularly with the inclusion of more African countries, these summits provide a valuable platform for cooperation on critical issues such as trade, investment, and sustainable development. The summit underscored the importance of a multipolar world where the perspectives and priorities of the Global South are recognised. For African nations, this was a vital opportunity to amplify their role in global economic governance. Meanwhile, Western partners of the continent, including the EU and Germany, monitored developments closely, reflecting the broader implications of BRICS’ growing influence.

To explore the key themes of the summit that unfolded amid significant global geopolitical shifts, APRI — the Africa Policy Research Institute and the University of Johannesburg are launching a thought leadership series on key themes surrounding BRICS. This series will delve into critical issues surrounding BRICS, such as energy transition, military coups, and human rights, and will aim to inform decision-making and strategic discussions.

To kick the series off, Ndzalama Mathebula writes about the paradigm shift presented by the new world order, and examines how the expansion of the BRICS bloc influences actors on the global stage to strategically place themselves as moral and responsible actors. Specifically, the piece explores the proponents of international law and the members of BRICS through the South Africa-Israel case at the International Court of Justice.

The second essay, by Adeelah Kodabux, explores BRICS Summit declarations, and how their implementation tends to lack follow-through. She argues that despite diverging societal dynamics, the BRICS configuration communicates a unified vision for the world order among its member nations through their annual intergovernmental declaration.

Finally, in the third piece, Makgamatha Mpho Gift weighs the pros and cons of establishing a unified monetary system for BRICS. The idea has generated mixed reactions among policymakers and economists, and the potential economic, political, and social implications should be analysed carefully.

1.

International law in the new world order: A BRICS paradigm shift towards post internationalism and heterarchy?

By Ndzalama Mathebula, University of Johannesburg

Introduction

This study explores the paradigm shift presented by the new world order and how the facets of the changing dynamics of world politics continue to influence international law, and examines how the expansion of the BRICS bloc influences actors in the international space to strategically place themselves as moral and responsible actors. The argument concurs with the theories of post international theory in international relations and the rise of heterarchy and deepens our understanding of the current shifts in international law.

This piece explores the proponents of international law and the BRICS bloc through the South Africa-Israel case at the International Court of Justice (ICJ). It specifically aims to review the influence of BRICS from an international law perspective. The significance of framing the piece from this angle stems from gauging the influence and reforms set to be ushered in by the growing influence of the intergovernmental group. The assessments further illuminate international relations, the changing global order and geopolitics. Proponents of heterarchy assume that there is a growing number of influential players in the international arena, such as the BRICS bloc. Examining these different spheres of influence can aid in forecasting shifts resulting from the group’s impact on the international, geopolitical paradigm. The bloc's expansion connotes the combined demographics and GDP of the BRICS countries. It further alludes to an ideological shift influencing how the BRICS states conduct their international relations.

Background: BRICS is an ideology that seeks to create a multilateral global system

The growth and expansion of the Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa (BRICS) intergovernmental organisation has presented an alternative form of world cooperation. This new ideological paradigm seeks to challenge the global, unipolar system by accentuating, recognising and leveraging the role of Global South countries and emerging economies in economic corporation, trade, infrastructural development and peace and security. The bloc is led by principles of sovereign equality, strategic cooperation, inclusiveness and, most importantly, multilateralism. One common factor amongst the BRICS nations is how all these states are hegemony in their respective continents and regions. As such, they have become a proportional representation of states from these regions. With such collective power, the states have become a much less coercive alternative that seeks to grow the influence of emerging economies and the Global South community. Much of the bloc’s foundation is grounded in the criticism they have echoed towards the Bretton Wood institutions and the unipolar dominance system of the Western states. However, the dominant actors have pushed back against the challenge of this unipolar system. Hence, world politics has been volatile in recent years. This volatility can be attributed to the clash of state interests, non-state actors and international norms. This is further understood within the facets of postinternationalism and heterarchy.

In challenging the unipolar system, BRICS has distinguished itself as a key player. This is evident in its approach, which can be characterised as soft power. As stipulated in their guiding principles, these countries have chosen to counter the dominant states by using less coercion toward fulfilling their national interests. Through these approaches, BRICS seeks to leverage and grow their countries in the context of the international community. Therefore, through its growth strategy and evolution, the bloc is emerging as an ideological paradigm which appeals most to emerging economies, the Global South and developing nations.

The dominance of BRICS countries is anchored in the perceived shortcomings and shortfalls of the global unipolar system, which the USA and European nations mostly dominate. The inauguration of new members at the 2024 summit alludes to several factors that influence the bloc and global politics. Firstly, the summit and its expansion mark the growing influence of the group among a number of states that share ambitions towards a multipolar system. This may trigger a new wave of Cold War ideological contestations or a Thucydides Trap. Secondly, the fact that Russia was the host country of the 2024 BRICS summit indicates a degree of hypocrisy within the bloc, bearing in mind the almost three-year Russia-Ukraine war. The silence from the bloc amid the atrocities in Ukraine demonstrates its inconsistent, separationist approach towards global challenges. As much as the intergovernmental organisation claims to comply with the principles of international law, especially in international peace and security, the group's actions indicate how their interests determine their responses to global challenges. This is further exacerbated by the non-alignment of South Africa with the UN’s Russia-Ukraine war resolution. At a larger scale, these aspects pertain to the discourse of power politics as a challenging factor in realising international law and ensuring consistency amongst states.

Postinternationalism and heterarchy

Postinternational theory and heterarchy approaches aid our understanding of world politics and play a critical role in gauging the changing dynamics of world politics and international law. Postinternationalism is defined as a pattern of world politics and trends sustained by non-state actors, international normative systems and the processes of globalisation. James N. Rosenau is recognised as the father of the post international theory (also referred to as the ‘turbulence paradigm’). He argues that world politics unfolds without the direct involvement of states, moving away from the classic international relations theories (realism, liberalism and constructivism) in elucidating world politics. Postinternational theory argues that the changing precepts of global politics have become too complex and intersectional to be solely defined within a single IR theory or paradigm. Instead, postinternationalism emphasises the role of non-state actors in configuring contemporary global politics as we know it.

Heterarchy is the ‘co-existence and conflict between differently structured micro- and meso- quasi-hierarchies. These compete with one another and overlap not only across borders but also across economic-financial sectors and social groupings’. A governing global system with multiple governing principles characterises a multi-nodal world in which heterarchy is inevitable. The theory is hailed for its ability to cut across the complex and intertwined web of global institutions, guiding ideologies, state actors driven by realism, global conflicts and the roles of non-state actors. The co-existence of these stakeholders and their contrasting views in the international community has given rise to a volatile world. On the other hand, heterarchy is harnessed to empower strategically situated players, especially those with substantial economic resources in a multi-nodal system who seek to leverage their momentum and influence in the global system.

International law and the BRICS effect

Since its establishment, BRICS has sought to alter the global system. The realm of international norms and laws has not been exempted from these reconfigurations. BRICS has significantly influenced international law and its normative systems and emphasises the importance of a multilateral approach towards solving global challenges through international law and its institutions. The BRICS effect in international law is nuanced, manifesting in economic trade, human rights, peace and security, and world development.

International law and its institutions have been criticised for serving the interests of Western states. Therefore, international law helps to reinforce the status quo of a unipolar world system. However, the robustness of this unipolar system has given rise to new prominent actors (i.e. BRICS) who continue to exemplify how a less coercive multilateral global system can represent all different states and actors. Amid the Israel-Palestine war, the South African case against Israel at the ICJ exemplifies the BRICS effect on international law and its institutions. In this instance, a global law court was used by a BRICS country to test the unipolar system of the UN by opening a case against an ally of the USA.

Here, the overlap between realism, postinternationalism and heterarchy is at play. This demonstrates that classic international relations theories cannot fathom the intricate web of international law and power politics from which the conflict of international norms and different hierarchies has emerged. Interestingly, BRICS opted for more key players and responsible actor positions, strategically positioning themselves as moral actors. The bloc’s soft power and multilateral approach toward altering the world system continues to legitimise their cause and agenda.

South Africa as a diplomatic actor and norm entrepreneur

Through the ICJ case, South Africa has leveraged and drawn strict inferences on its soft power and diplomacy. The case has provoked numerous reactions: South Africa has been labelled antisemitic; at the same time it has received massive support from multiple emerging economies, including Bangladesh and Namibia, who regard the country as a moral and responsible emerging actor. Through this case, South Africa could shed its perceived identity as a passive bystander or an instigator of war. The ICJ case has altered the foreign policy landscape of South Africa and has further tested the unipolar system of the UN. Through these points of analysis, it can be deduced that South Africa once again seeks to be labelled as a critical player in the new world order and to enhance its legitimacy and its heroic, hegemonic title beyond the African continent.

Herein, we are exposed to the synchronised interplay of postinternationalism and the rise of heterarchy and witness the co-existence of, and conflict between, multiple hierarchies in the globalised, interconnected world. Firstly, by challenging the unipolar system, the UN court, as a supposedly unbiased entity that sees through the interests of every country without the influence of power politics, is being tested. Secondly, we are exposed to a series of international norms and regional ideologies shaping global politics: As BRICS has illuminated an alternative structure towards world cooperation and politics, several countries are being enticed to adopt and harness multilateralism as the most appealing paradigm of world politics. Third, heterarchy is demonstrated through South Africa's position as a moral actor through the ICJ case. Diplomatically, the case has shown how global conflict resolution should and can be addressed in a multilateral world, meanwhile earning South Africa recognition as a responsible and moral actor. South Africa has again used this case to enhance its legitimacy beyond the African continent. This concurs with the ideals of heterarchy, where strategically positioned actors are empowered to extend their influence and power in the global arena.

It is no secret that countries constantly seek to enhance and maximise their power and sovereignty. However, an interesting point that has emerged with the evolution of international relations is the methods countries have adopted to enhance their power and influence on the global stage. The analysis asserted here aims to demonstrate how countries will always respond to transnational or global conflicts in a manner that suits their national interest. However, this perspective does not dismiss the fact that countries respond through hard or soft power for peace and security matters. Instead, the argument is that action taken by states to respond and assist in conflicts abroad can be regarded as a diplomatic strategy to both achieve peace and security and enhance the legitimacy of their country.

The BRICS summit and the surmised heterarchy exhibited by BRICS member states indicate how the intergovernmental organisation will adopt international law to further its ambitions for multipolarity and influence on global politics. The latter also speaks to BRICS-Africa relations, where many African states perceive the group as a more suitable exemplar on the global stage, boosting the footprint of the bloc and the new world order. The summit provided an opportunity for emerging states to strengthen relations and realign their ambitions for multipolarity. At the same time, it delineated how the bloc can remain a strategic player in the changing international arena and avoid inheriting a system never designed for their development.

2.

BRICS configuration's representation of the majority world

By Dr. Adeelah Kodabux, Director of LEDA

Background

Since 2009, Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa (BRICS) have issued an intergovernmental declaration every year. The Head of State reads each annual declaration from the hosting country, which alternates among the five countries. Although the host country’s Head of State delivers the declaration verbally on the last day of the BRICS leaders’ gathering, it remains an intergovernmental statement expressing the shared position of the five BRICS countries. It is a documented statement based on the previous ministerial and other government-approved exchanges among the five countries.

Under Russian chairmanship, the theme for this year’s BRICS summit was entitled ‘Strengthening Multilateralism for Equitable Global Development and Security’. The first intergovernmental summit in 2009 was primarily concerned with the emerging countries’ resilience to the global financial crisis, which led to them being regarded as challengers of the status quo in the world economic order. Fifteen years later, the group’s focus has transformed from the five countries’ concerns about advanced economies’ vulnerability to financial crises to becoming collectively involved in finding solutions for global development problems and creating new areas for cooperation among themselves and countries from the majority world. Meanwhile, global geopolitical events, including Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and escalating tensions in the Southwest Asian and North African (SWANA) region, have spiralled into crises.

Given the evolution of BRICS from a financial buzzword in 2001 to an intergovernmental configuration in 2009, this article aims to explore the essence of the first ten annual declarations. It argues that, due to their response to the global financial crisis, there were noticeable successes in transforming the members’ declared statements into implemented actions during their initial years. Based on content analysis, three questions are asked. First, whose interests does the BRICS configuration represent? Second, what are the common themes in their declarations? Third, is there a gap between their declared statements and practical outcomes?

The insights gained from this study contribute to ongoing conversations about the purpose and global impact of BRICS. The study concludes that despite differences in their respective country dynamics and governmental responses to global crises, the five countries manage to collectively construct the idea that their extended alliance is intended to enhance world order. However, beyond their declarative statements, there is an ongoing lack of clarity about BRICS policy coordination and implementation, which suggests that consistent annual gatherings alone are insufficient measures of their success. Implementing declared statements matters to substantiate the BRICS notion of acting in the majority world’s interests.

Background on the intergovernmental declarations

The annual BRICS leaders’ declaration contains a set of documented commitments proclaiming the intentions and shared vision of the five countries’ governments for the world order and their potential for collective coordination to address matters related to global development, economic growth and international affairs. Although the declarations are non-binding documents, they are noteworthy because they communicate shared perceptions from the five different governments on various topics. They receive considerable media attention and coverage in foreign policy analyses when issued. The documents are not meant to impose legal obligations on any of the governments. Instead, the declarations echo their harmonised vision, their perceptions of matters of mutual concern in the world order, their planned course of action to address global challenges and their commitments towards one another.

Over time, the BRICS configuration has transformed into an unlikely intergovernmental convergence. Even though they share few economic and political commonalities – since they follow diverging domestic governance models and operate their respective economies according to contrasting ideologies – since 2009 the five countries have managed to sustain their grouping as an intergovernmental politico-economic arrangement. This setup has been artificially established since it did not materialise intrinsically as a result of traditional intergovernmental initiatives. Instead, Jim O’Neill coined the acronym ‘BRIC’ in 2001 in a Goldman Sachs’s report comparing the real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth of the initial four countries with the advanced G7 economies. He predicted that the emerging BRIC markets would outperform some of the G7 in the long run. Building on this report’s narrative, especially in the aftermath of the 2007-8 financial crisis, which affected developed economies more than emerging countries, the four BRIC countries started to reflect on the prospect of their collective coordination to address world problems.

While the millennium’s first two decades have seen a surge in the number of country acronyms of a semi-peripheral character, none has matched the degree of intergovernmental formalisation achieved by BRICS. For example, VISTA, E7, N11, CIVETS, MINT, BRIICS and TIMBI are other abbreviated country groupings from the non-core sphere of the international system. The BRICS configuration is the most remarkable regarding real-world output among these groupings. Over the years, the once neutrally coined acronym in a Western investment bank’s report transformed into an intergovernmental organisation capable of articulating coordination over important areas in global politics. The five states have not surrendered any power through their interactions. Instead, there is an attempt at harmonisation regarding what they consider to be pressing global development issues.

BRICS declarations’ overall essence: Whose interests do they represent?

Based on a systematic content analysis of the first ten declarations, Table 1 describes how BRICS intergovernmental declarations fluctuate in length. The content analysis indicates that the range of items they cover is broad. Nevertheless, there is one common pattern. Although the annual statements may be structured differently, every declaration emphasises the idea that the BRICS configuration speaks on behalf of low-income, emerging and developing countries.

Table 1: Overview of BRICS’ first ten declarations

| Year | Host Country | Declaration Statement | Number of Statement Points | Extract from Declaration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | Russia | Joint Statement of the BRIC Countries' Leaders | 16 | ‘We are committed to advance the reform of international financial institutions, so as to reflect changes in the global economy. The emerging and developing economies must have greater voice and representation in international financial institutions’ (note 3). |

| 2010 | Brazil | Second BRIC Summit of Heads of State and Government: Joint Statement | 31 | ‘We stress the central role played by the G-20 in combating the crisis through unprecedented levels of coordinated action…’ (note 3). |

| 2011 | China | Third BRICS Summit: Sanya Declaration Broad Vision, Shared Prosperity |

32 | ‘We affirm that the BRICS and other emerging countries have played an important role in contributing to world peace, security and stability…’ (note 5). |

| 2012 | India | Fourth BRICS Summit: Delhi Declaration BRICS Partnership for Global Stability, Security and Prosperity |

50 | ‘We stand ready to work with others, developed and developing countries together, on the basis of universally recognized norms of international law and multilateral decision making, to deal with the challenges and the opportunities before the world today. Strengthened representation of emerging and developing countries in the institutions of global governance will enhance their effectiveness in achieving this objective’ (note 4). |

| 2013 | South Africa | Fifth BRICS Summit BRICS and Africa: Partnership for Development, Integration and Industrialisation |

47 | ‘We are open to increasing our engagement and cooperation with non-BRICS countries, in particular Emerging Market and Developing Countries (EMDCs), and relevant international and regional organisations’ (note 3). |

| 2014 | Brazil | 6th BRICS Summit: Fortaleza Declaration Inclusive Growth: Sustainable Solutions |

72 | ‘We renew our openness to increasing engagement with other countries, particularly developing countries and emerging market economies, as well as with international and regional organisations, with a view to fostering cooperation and solidarity in our relations with all nations and peoples’ (note 3). |

| 2015 | Russia | VII BRICS Summit: Ufa Declaration BRICS Partnership – a Powerful Factor of Global Development |

77 | ‘The global recovery continues, although growth remains fragile, with considerable divergences across countries and regions. In this context, emerging markets and developing countries (EMDCs) continue to be major drivers of global growth’ (note 11). |

| 2016 | India | 8th BRICS Summit Building Responsive, Inclusive and Collective Solutions |

110 | ‘We agree that BRICS countries represent an influential voice on the global stage through our tangible cooperation, which delivers direct benefits to our people. [We will work] to ensure that the increased voice of the dynamic emerging and developing economies reflects their relative contributions to the world economy, while protecting the voices of least developed countries, poor countries and regions’ (note 3). |

| 2017 | China | 9th BRICS Summit: BRICS Leaders Declaration BRICS: Stronger Partnership for a Brighter Future |

71 | ‘Our cooperation since 2006 has fostered the BRICS spirit featuring mutual respect and understanding, equality, solidarity, openness, inclusiveness and mutually beneficial cooperation, which is our valuable asset and an inexhaustible source of strength for BRICS cooperation… We have furthered our cooperation with emerging markets and developing countries (EMDCs). We have worked together for mutually beneficial outcomes and common development, constantly deepening BRICS practical cooperation which benefits the world at large’ (note 3). |

| 2018 | South Africa | 10th BRICS Summit: Johannesburg Declaration BRICS in Africa: Collaboration for Inclusive Growth and Shared Prosperity in the 4th Industrial Revolution |

102 | ‘We reaffirm our commitment to the principles of mutual respect, sovereign equality, democracy, inclusiveness and strengthened collaboration’ (note 5). |

On account of the content analysis and trends observed in the declarations, it is observed that the BRICS leaders and their government-sanctioned platforms are actively involved in discursive practices which confirm that the BRICS configuration shares a common vision in the interests of the majority world: they intend to redress the inequalities caused by the ways of functioning of developed economies. The BRICS initial intergovernmental declarations present their own agenda from a positive angle and as a better model for the majority world (Kodabux, 2023). They are deploying strategies to appeal to stakeholders from BRICS and convince developing countries that the five governments are working collectively in their interests on the global stage.

BRICS common themes

Common themes observable in BRICS’ statements can be grouped under five categories: ‘practical cooperation’, ‘global economic governance’, ‘international security’, ‘cultural diversity’ and ‘principles’. These capture the configuration’s ideas: ‘[First,] [p]ractical cooperation among BRICS countries and partnership with other countries in diverse sectors has the potential to reach concrete outcomes in international society’s interests. [Second,] [t]he existing global financial architecture lacks transparency and is discriminatory for emerging and developing countries. The global economic governance structures need to be reformed to reflect inclusiveness and representativeness in the world order. [Third,] [g]lobal threats and challenges exist in different forms and jeopardise international security. Poor and developing communities are particularly susceptible. Existing institutions should be reformed to address conflicts and threats and reach consensus-based decisions multilaterally. [Fourth,] cultural diversity is the foundation of BRICS cooperation. Sustainability of common vision and intra-BRICS projects [are] achieved through exchanges and cooperation in various civil society areas (media, think tanks, youth, parliament forums, local governments, trade union forums, etc.). [Fifth,] [a]ll of the previous themes are based on shared “principles of openness, solidarity and mutual assistance” amongst other ideals and values cherished by the BRICS countries’ (Kodabux, 2023).

A preliminary conclusion derived from the intergovernmental declarations is that although the five states operate differently, they can articulate their vision for global economic governance, multilateralism in international affairs, or fairer trade practices using principles that appeal to developing countries. Based on an analysis of BRICS documents, these principles include: ‘greater voice’, ‘fair burden-sharing’, ‘shared perception’, ‘coherence’, ‘pragmatism’, ‘legitimacy’, ‘resistance to unilateralism’, ‘common but differentiated responsibility’, ‘openness’ and ‘rules-based order’. Expressed in relation to redressing North-South development imbalances, the principles are not rhetorical statements: They suggest the BRICS countries operate differently from developed economies. Indeed, they have, in their early years, demonstrated that they act in the interests of the majority world, as evidenced in the next section.

Declarations vs implementation: What do we know about it?

The content analysis of the declarations indicates that the cooperation areas among BRICS countries were created first on a discursive level. Some of their declarations about working for the majority of the world’s interests have manifested in practical responses to the 2007-8 global financial crisis. For example, the BRICS governments used the argument about how their economies fared better than the G7 economies during the crisis to set the agenda for the G20 summit in 2009 (The Economist, 2009). The G20 has served as the BRICS’ ‘premier forum for [their] international economic cooperation’ (G20 Information Centre, 2009). BRICS also directed discussions of the 2010 G20 summit according to their agenda.

Between 2008 and 2010, the intergovernmental group of emerging economies was successful in convening discussions about the topics of openness, meritocracy, rules-based order and fairness. Although the G20 is an informal bloc whose summit declarations are non-binding, akin to the other blocs such as the G7 or G8, it is an important space for major industrialised and developing economies to discuss matters pertaining to international financial stability. The G20 summit is an expansion of ‘the centre of global governance to include ascending powers alongside advanced ones, and to give each equal, institutionalised involvement and influence in the central club’ (Kirton, 2010 p. 2). Due to this summit’s representation as the centre for global economic governance and the space it offers to discuss matters about the health of the world economy, the BRICS leaders have stressed the central role played by the G20,as opposed to the G7 or G8, in dealing with financial issues (BRICS Information Centre, 2009 notes 1–2; 2010 note 3; 2011 notes 14–15; 2012 note 7). In their initial BRICS declarations (2009 note 3; 2010 notes 10–11; 2011 notes 15–16; 2012 9–10), the leaders recommended actions which have been addressed and implemented at the G20 summit, namely in the International Monetary Fund (IMF) quota reforms, whereby the members committed to transfer a share of the quotas to underrepresented countries.

Additionally, the four initial BRIC leaders also requested urgent reforms in the World Bank. They demanded ‘a substantial shift in voting power in favour of emerging market economies and developing countries’ (BRICS Information Centre, 2009). Faced with this pressure, the World Bank initiated its ‘first general capital increase’ in over twenty years, which resulted in a ‘shift in voting power to developing countries’ (World Bank, 2010). Requesting stronger and more flexible aid from multilateral development banks has been another area where the political class of the configuration advocated for support of developing economies. In their 2010 intergovernmental declaration, they stated: ‘We support the increase of capital, under the principle of fair burden-sharing, of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development and of the International Finance Corporation, in addition to more robust, flexible and agile client-driven support for developing economies from multilateral development banks’ (BRICS Information Centre, 2010). The outcome was that during the 2010 G20 summit, the members, along with a significant contribution from BRIC countries, committed to increase the resources available to the IMF ‘by USD 6 billion through the proceeds from the agreed sale of IMF gold … [which expanded] the IMF’s concessional financing for the poorest countries’ (International Monetary Fund, 2010). BRICS governments also promoted the implementation of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and ensured that the poorest countries’ efforts are not hindered due to the aftereffects of the financial crisis. As a result, they called for policy recommendations, ‘technical cooperation, and financial support to poor countries in implementation of development policies and social protection for their populations’ (BRICS Information Centre, 2010 note 15). The G20 members responded to this call by committing ‘to put jobs at the heart of the recovery, to provide social protection, decent work and also to ensure accelerated growth in low income countries’ (G20 Seoul Summit Declaration, 2010 p. 1).

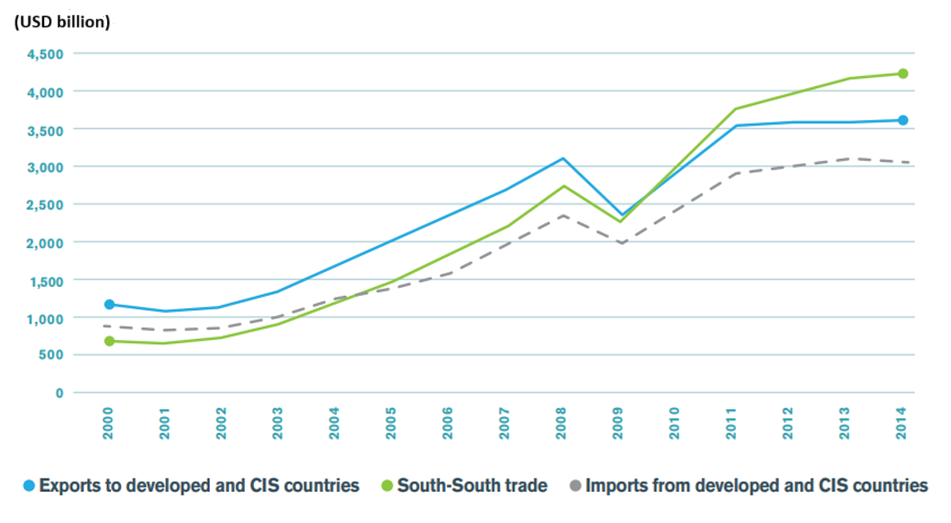

More recently, the BRICS countries have succeeded in demonstrating their intent to expand their cooperation beyond their five members. Since 2023, Iran, the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Egypt and Ethiopia have also become members of the BRICS alliance. The idea for a ‘BRICS Plus cooperation’ was formulated in their 2017 intergovernmental statement. While there are concerns about this expansion on account of its implications for Western hegemony, it is also relevant to underline that the BRICS Plus alliance is to date an informal arrangement. Non-BRICS countries and other regional organisations interact with BRICS countries according to individual interstate arrangements rather than through a formalised channel ‘with the group as a whole’ (European Parliament 2024). In fact, a related gap is observed when exploring the connection between the declared statements and the implemented actions. According to Pioch (2016), little is known about ‘BRICS [collective] policy coordination and cooperation’. For example, even if south-south trade intensified among developing countries in the first fifteen years of the millennium, as shown in Figure 1, it is inconclusive whether this was the result of BRICS initiatives or pre-existing agreements. When researching BRICS Trade Ministers’ documents, there is no revelation of common strategies which they might have developed as a result of their meetings (BRICS Trade Ministers, 2011–17). Instead, these documents expound on a conception of practical economic cooperation for open, fairer international trade in the interests of emerging and developing economies.

Figure 1: Developing economies’ merchandise trade with developing, developed and commonwealth independent states

Note. The data show how South-South trade plummeted between 2008 and 2009 but escalated after 2009.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the BRICS intergovernmental declarations contain multiple messages and ideas about the purpose and vision of the configuration for the majority world. There is an observable pattern in their discussion of issues that they frame as matters of mutual concern for present and future world politics. Despite the stark differences in their individual domestic settings, the five countries continue to be able to convene during their yearly summit and to issue their annual intergovernmental declaration. They have added new items to consider and have, over the years, welcomed the idea of adding new members to the configuration. In addition, contemporary geopolitical events continue to test their alliance. However, our findings show that declared statements do not match the practical outcomes of the BRICS countries’ collective initiatives. In other words, there is a need to address the gap between declaration and implementation to substantiate the claim that the BRICS countries act in the interests of the majority world.

The BRICS annual intergovernmental declarations merit further analysis beyond the first ten years of this article's scope. Annual gatherings at interstate or ministerial levels are insufficient measures of the configuration’s successes. Beyond their declarative statements, additional in-depth studies are required to explore the extent of BRICS collective policy coordination.

3.

The BRICS currency conundrum: Weighing the pros and cons of a unified monetary system

By Makgamatha Mpho Gift, South African BRICS Youth Association (SABYA)

Introduction

The BRICS countries – Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa – represent more than 40% of the global population and nearly 24% of the global GDP (Zharikov, 2023). In the last twenty years, they have undergone substantial economic expansion and acquired growing political clout, prompting talks about greater economic integration (Irwin, 2024). As part of the implementation of a unified currency among these countries, their national currencies would be replaced with a single monetary unit (Bharat, Gautam & Rastogi, 2024), with the aim of bolstering the overall economic stability of these nations, streamlining trade and investment, and mitigating fluctuations in exchange rates. Although the concept has potential benefits, it faces challenges, such as the need to create a new financial system during a time of political and economic conflicts. The implementation of the currency would therefore be ambitious and intricate compared to other suggestions aimed at promoting integration among the BRICS countries.

Establishing a unified currency among the BRICS nations is not just an economic issue. It also has significant geopolitical implications (Bharat et al., 2024). Implementing such a currency could change the allocation of worldwide financial power, challenging the current dominance of traditional economic centres like the US and the EU (Ioannou et al., 2023). This proposed adjustment adds another layer of strategic importance to the discussion, making it a topic of significant interest for politicians, economists and foreign relations experts. This assessment therefore comes at a crucial juncture, examining the potential economic, political and geopolitical implications of a unified BRICS currency which could significantly alter global trade dynamics, financial stability and the balance of power in international monetary systems. This paper discusses the benefits and drawbacks of adopting a common currency among the BRICS states.

A key research gap in the BRICS currency conundrum lies in the lack of comprehensive analysis of the potential economic, geopolitical and financial implications of a unified monetary system within a bloc of countries with varying economic structures, political agendas and degrees of financial integration. Therefore, the paper examines the historical context of the BRICS economies, explores the theoretical foundations of monetary unions and assesses case studies from other regions that have pursued similar integration initiatives. Thus the paper presents an unbiased perspective on the viability of adopting a single currency as a means to enhance economic integration among the BRICS countries.

Theoretical framework

The analysis of the feasibility and consequences of a unified currency among the BRICS countries is based on the theoretical framework of Optimal Currency Areas (OCA) introduced by economist Robert Mundell (Singh, 2023). This theory delineates the requirements for multiple nations to derive advantages from a common currency, encompassing the ability for labour and capital to move freely, the capacity for prices and wages to adjust easily and the presence of comparable business cycles among the participating countries.

The ability of labour and capital to move freely within the BRICS countries is constrained by significant geographical distances, distinct regulatory frameworks and varying degrees of infrastructure development (Zharikov, 2023). Furthermore, the economic cycles of these countries do not exhibit strong synchronicity, as each nation undergoes distinct growth rates, inflation levels and economic shocks (Irwin, 2024). The OCA theory highlights the significance of fiscal integration and political coherence, both of which are currently absent among BRICS countries due to their unique political systems and governance structures (Singh, 2023). By utilising this theoretical framework, we may enhance our comprehension of the economic and institutional modifications necessary for a smooth transition to a unified currency among the BRICS nations.

Review and analysis of literature

Countries such as Brazil and South Africa, characterised by varied but relatively small economies, may gain from reduced exchange rate volatility and enhanced trade stability (Bharat et al., 2024). Nonetheless, they may encounter inflationary risks if economic circumstances among member states diverge. Amidst stringent Western sanctions, Russia perceives a unified BRICS currency as a possible means to circumvent the dollar-centric financial system. Yet, this may exacerbate its isolation from wider global markets (Zharikov, 2023). India exercises caution, as its expanding economy is interconnected with both Western and BRICS countries, and it may opt to preserve monetary flexibility (Harriss, 2020). China, due to its substantial economic stature, stands to gain the most from such a system, but it risks estranging other members if it asserts excessive influence over the currency's administration (Roberts, 2022). Although a unified BRICS currency could provide benefits such as increased global influence and monetary autonomy, varying economic circumstances and geopolitical tensions among member states hinder the practicality of this initiative. Each nation must evaluate these advantages and disadvantages prior to committing to a collective monetary future.

The concept of a unified currency

This concept seeks to improve economic integration, simplify financial operations and strengthen the overall economic stability of the BRICS bloc. To comprehend this notion, one must analyse the operational mechanisms, necessary institutional frameworks and probable ramifications for the global financial system (Pierret and Howarth, 2023). The implementation of a unified currency would entail crucial components. First and foremost, it would be necessary to establish a synchronisation of monetary policies among BRICS nations, encompassing the establishment of uniform interest rates, inflation objectives and exchange rate strategies (Bharat et al., 2024). A governing body, similar to the European Central Bank in the Eurozone, would supervise and execute these policies (Irwin, 2024). Moreover, the integration of fiscal policy would be imperative, encompassing the implementation of uniform budgetary regulations and the establishment of procedures for fiscal transfers among member states to tackle economic inequalities. Furthermore, the centralised management of the unified currency issue would be overseen by a central agency, which would regulate its supply in order to ensure price stability (Cheng, 2023). Ultimately, a key objective would be to eradicate variations in exchange rates across BRICS nations, so promoting seamless trade and investment activities while diminishing the risks and expenses involved with currency conversion.

The impact of a unified BRICS currency on the worldwide financial system will likely be substantial. By eliminating the risk of fluctuating exchange rates and reducing the costs associated with transactions, the implementation of a common currency inside the bloc might facilitate commerce and investment (Lukonga, 2023). This would result in the creation of a more integrated and competitive economic area, which would in turn attract higher levels of foreign direct investment. Furthermore, the creation of such a currency has the potential to alter the balance of global financial power by undermining the supremacy of the US dollar and the euro (Lukonga, 2023). This would result in an enhanced influence of BRICS states in global financial markets and international economic policy deliberations. Moreover, the adoption of a single currency would probably result in increased consolidation of financial markets within the BRICS alliance, facilitating the movement of capital, strengthening the availability of funding and promoting stronger economic expansion among member nations.

The historical context of BRICS economies

The BRICS nations have unique historical and economic paths that have influenced their current economic situations. Brazil, the most prominent economy in South America, has a historical narrative characterised by colonisation, a shift towards a republic and episodes of economic instability (Cardoso and Faletto, 2024). The region’s economy depends on agricultural, mining and energy resources. Brazil's ascent to the status of a significant global economy can be attributed to the identification of extensive oil reserves and agribusiness growth. Nevertheless, the country has encountered political instability, corruption and income disparity, which have hindered its progress (Cardoso and Faletto, 2024).

Russia's economic history is defined by its transition from the Tsarist Empire to the Soviet Union and, ultimately, to the Russian Federation (Zhuravskaya, Guriev & Markevich, 2024). The Soviet era was characterised by a system of centralised economic planning and the process of industrialisation, which was later followed by the implementation of economic liberalisation and privatisation in the 1990s (Zhuravskaya et al., 2024). Russia's economy relies primarily on its abundant natural resources, namely oil and gas, which have positioned it as a dominant player in worldwide energy markets (Bricout, Slade, Staffell & Halttunen, 2022).

India's economic trajectory is shaped by its history of colonisation, the economic policies implemented following independence in 1947 and its recent period of fast growth (Harriss, 2020). After gaining independence, India implemented a mixed economy that involved substantial government intervention (Harriss et al., 2020). The main objectives were to promote self-sufficiency and foster industrial growth. The economic liberalisation that occurred in the early 1990s allowed for the full realisation of the country’s potential, resulting in significant growth mostly fueled by the services industry, specifically information technology (Castells, 2020). However, the country still faces problems such as poverty, inadequate infrastructure and a complicated legal framework that can hinder entrepreneurial activities.

The economic ascent of China is one of the most noteworthy global advancements in recent decades. Following a prolonged period of seclusion and economic stagnation as a result of Maoist policies, the nation initiated a sequence of economic reforms in 1978 under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping (Roberts, 2022). The implementation of these changes facilitated China's shift from a centrally planned economy to a market-oriented one, resulting in swift industrialisation, urbanisation and unparalleled economic expansion (Roberts, 2022). China's strong industrial capabilities and reliance on exports have propelled it to become the second-largest economy globally. However, China is confronted with obstacles such as decelerating economic expansion and deterioration of the environment (Lu, Zhang, Xing, Wang, Chen, Ding, Wu, Wang, Duan & Hao, 2020).

The economy of South Africa is influenced by its abundant natural resources, as well as its history of apartheid. The fall of apartheid in 1994 presented fresh economic prospects and difficulties as the nation endeavoured to assimilate into the worldwide economy (Sindane, 2020). The economy of South Africa is characterised by diversification, with prominent industries such as mining, manufacturing and services (Bhorat, Lilenstein, Oosthuizen & Thornton, 2020). Nevertheless, it grapples with elevated levels of unemployment and social inequality. The enduring impact of apartheid is seen in the economic and social policies of the country as it seeks comprehensive growth and development.

Comprehending the historical circumstances of these economies is crucial for assessing the practicality and consequences of a unified BRICS currency. Any endeavour to integrate the monetary systems of different countries must consider the distinctive economic history and current obstacles each country faces. The variation in their economic bases, levels of advancement and policy preferences underscores the intricacy of establishing a cohesive monetary framework that would benefit all participating countries.

Pros (potential benefits of a BRICS unified currency)

-

Economic stability

Using a unified currency among the BRICS nations might significantly improve economic stability by mitigating fluctuations in exchange rates and promoting a more predictable business climate (Singh, 2023). Volatility in exchange rates can significantly disrupt trade and investment, resulting in uncertainty and higher expenses for enterprises operating across the borders of BRICS countries (Lukonga, 2023). Implementing a unified currency would eradicate this volatility, enabling seamless and more effective cross-border transactions. The ensuing stability of the BRICS bloc might attract additional foreign investment as investors are more assured of the economic predictability of the region (Singh, 2023). Moreover, implementing a single currency could assist in reducing the effects of external economic disturbances by facilitating a more synchronised and coherent monetary policy reaction. Adopting this collaborative strategy could strengthen the ability of BRICS economies to withstand global financial disruptions, thereby promoting long-term economic growth and stability (Larionova and Shelepov, 2022). Through the synchronisation of monetary policies and the establishment of a more expansive and unified economic region, the BRICS nations have the potential to accomplish a higher degree of economic stability, which would be more difficult to achieve individually. -

Reduced transaction costs

The enactment of a unified currency across the BRICS nations would substantially decrease transaction expenses for trade and investment within the member countries (Kumar, Ghai, Tyagi & Gupta, 2020). At present, businesses and investors are required to deal with the intricacies and costs related to currency conversion, which include charges and unfavourable exchange rates (Bharat et al., 2024). A unified currency would enhance the efficiency of financial transactions by eliminating the currency conversion requirement, resulting in faster, more cost-effective processes. The decrease in transaction costs would specifically advantage small and medium-sized firms (SMEs), which frequently encounter greater expenses for currency conversion compared to larger corporations (Angelovska & Valentinčič, 2020). Reducing transaction costs could also improve price transparency and competition, facilitating easier price comparisons for consumers and businesses across different countries (Kumar et al., 2020). The resultant trade efficiency enhancement and cost reduction could stimulate increased economic activity and integration among BRICS nations, promoting a more vibrant and integrated economic zone. This would create a more favourable atmosphere for growth, innovation and investment, thereby strengthening the BRICS bloc's position in the global economy (Angelovska & Valentinčič, 2020). -

Enhanced political cooperation

An integrated BRICS currency has the potential to facilitate political collaboration among the bloc by promoting stronger economic connections and establishing a common objective (Kondratov, 2021). Establishing and managing a single currency necessitates considerable collaboration and coordination on monetary and fiscal policies, requiring constant communication and decision-making among the member nations. Enhanced engagement of individuals can foster confidence and promote shared comprehension, thus mitigating political tensions and bolstering diplomatic ties (Kondratov, 2021).

Increased political collaboration will also enable BRICS nations to portray a more cohesive stance in global economic forums, augmenting their combined sway over international economic policies and institutions. Moreover, a common currency might represent unity and dedication to sustained collaboration, fostering increased integration in several domains such as commerce, infrastructure advancement and safeguarding (Larionova & Shelepov, 2022). By enhancing the alignment of their economic interests, the BRICS nations have the potential to attain higher levels of stability and prosperity, both on an individual basis and as a collective entity. If fulfilled, this would also enable them to establish a more influential and powerful presence on the global scene.

Cons and risks of a unified BRICS currency

-

Economic divergence

Economic divergence refers to the process by which the economies of different regions or countries move apart from each other, resulting in increased disparities in terms of economic growth, development and prosperity (Frankema, 2024). An important risk in creating a single BRICS currency is the economic disparity among the BRICS nations’ economic structures, growth rates and degrees of development: China's economy is characterised by a strong emphasis on industrialisation and exports, whereas India's economy is reliant on services and domestic consumption (Lu et al., 2020). Russia and Brazil are significant exporters of commodities, and have economies that are highly responsive to global price swings in oil and agricultural products, respectively (Cardoso & Faletto, 2024). South Africa, with its distinctive socio-economic difficulties, introduces an additional level of complexity. The divergences in economic cycles among BRICS countries result in a lack of synchronisation, posing challenges in implementing a uniform monetary policy that caters to all members (Kondratov, 2021). The issues are intensified by diverse inflation rates, varying degrees of budgetary discipline and differing economic policy agendas. Without a mechanism to rectify these differences, implementing a single currency could result in economic imbalances, with certain countries reaping benefits while others suffer. The economic difference may put pressure on the political unity crucial for the effective functioning of the currency union, ultimately jeopardising its stability and long-term viability (Kumar et al., 2020). -

Political and transition

The establishment of a unified currency for the BRICS nations faces disadvantages and hazards, mostly centred on political and governance concerns. First, it necessitates substantial political convergence and confidence among the member nations, which might be difficult due to the varied political landscapes and economic interests within the bloc (Liu & Papa, 2022). Tensions regarding currency exchange rates, monetary policies and economic plans have the potential to strain ties and impede the implementation process. Furthermore, there are worries surrounding governance, namely addressing the nation that would have the most influence in decision-making processes and how conflicts would be resolved (Petrone, 2022). These concerns could result in power struggles and unfair outcomes. In addition, the independence of each member country could be undermined, as a united currency requires a certain level of coordination and centralisation of fiscal policies, which may restrict individual economic independence (Liu et al., 2022). Furthermore, external geopolitical factors and global economic forces may have an impact on the stability and long-term success of a unified BRICS currency system, making the stability and value of a united BRICS currency more complex in the international market (Zharikov, 2023). Therefore, although the idea promises much economically, it is essential to evaluate the drawbacks and risks before undertaking such a substantial monetary integration project. -

Implementation and transition cost

The introduction of a consolidated currency for the BRICS nations would encounter significant difficulties and expenses (Kondratov, 2021). The logistical intricacies alone, such as the synchronisation of financial systems, the establishment of a central bank and the harmonisation of monetary policies, would necessitate substantial coordination and resources. The economic discrepancies among the BRICS countries have the potential to exacerbate these issues, resulting in disparities in inflation rates, levels of unemployment and economic resilience (Zharikov, 2023). This, in turn, might destabilise the united currency. Furthermore, the expenses associated with implementing a new currency system, such as issuing new money, modernising financial infrastructure and providing public education, could be excessive, particularly for economically disadvantaged populations (Batista, 2021). Meanwhile, the act of negotiating the political terrain and achieving consensus on important issues, such as exchange rate systems and governance structures, has the potential to impede or even disrupt the implementation process (Zharikov, 2023). Therefore, although the idea of a consolidated currency for the BRICS nations has advantages, the actual challenges and expenses involved emphasise the importance of preparation, collaboration and economic readiness.

Policy recommendations

A variety of policy recommendations address this complex issue:

Phased approach: Adopt a gradual method for integration, first with more collaboration in areas such as monetary policy, procedures for maintaining exchange rate stability and financial regulation. An incremental approach can establish trust, detect issues at an early stage and reduce dangers associated with a quick shift to a unified currency.

Flexibility and adaptability: Create a versatile structure that enables modifications in response to the economic and political circumstances of member nations. Acknowledge and adapt to the varied economic frameworks, stages of advancement and policy preferences inside BRICS in order to guarantee fair and inclusive involvement and advantages.

Institutional strengthening: Prioritise the strengthening of institutional frameworks, including central banking capabilities, financial oversight mechanisms and dispute resolution mechanisms. Robust institutions are essential for effective governance and management of a unified currency system.

Public engagement and education: Conduct thorough public outreach and educational initiatives to enlighten and equip individuals, businesses and stakeholders with knowledge about the advantages, dangers and procedures associated with implementing a standardised currency. For any monetary integration endeavour to be successful, it is essential to have transparency and gain public support.

Risk mitigation strategies: Develop detailed risk mitigation methods that specifically target potential economic shocks, uneven effects on member states and external geopolitical pressures. It is imperative to have contingency measures in place to effectively handle crises and guarantee the stability of the unified currency.

International cooperation: Interact with international financial institutions, such as the IMF and World Bank, as well as significant economies outside BRICS, to obtain support, exchange best practices and utilise knowledge in the integration of currencies and stabilisation of monetary systems.

Conclusion

The prospect for a unified BRICS currency offers opportunities and challenges. A unified currency might improve trade efficiency among member nations, diminish reliance on the US dollar and promote more economic stability inside the bloc. This transition may enable BRICS nations to exert greater influence on the global economic stage, potentially equalising competition against prevailing currencies. However, the adoption of a unified monetary system involves significant dangers, such as the necessity for strong budgetary coordination, possible economic differences among member nations and difficulties in establishing a central authority to oversee the currency. The success of this programme will ultimately hinge on the BRICS nations' willingness to collectively negotiate these challenges, balancing their varied economic interests while pursuing greater unity in a swiftly evolving global context.

References

BRICS configuration's representation of the majority world

BRICS Information Centre. (2009). Joint statement of the BRIC countries’ leaders. http://www.brics.utoronto.ca/docs/090616-leaders.html

BRICS Information Centre. (2010). 2nd BRIC summit of heads of state and government: Joint statement. http://www.brics.utoronto.ca/docs/100415-leaders.html

BRICS Information Centre. (2011). Sanya declaration. http://www.brics.utoronto.ca/docs/110414-leaders.html

BRICS Information Centre. (2012). Fourth BRICS summit: Delhi declaration. http://www.brics.utoronto.ca/docs/120329-delhi-declaration.html

BRICS Information Centre. (2013). BRICS and Africa: partnership for development, integration and industrialisation: eThekwini declaration. http://www.brics.utoronto.ca/docs/130327-statement.html

BRICS Information Centre. (2014). The 6th BRICS summit: Fortaleza declaration. http://www.brics.utoronto.ca/docs/140715-leaders.html

BRICS Information Centre. (2015). VII BRICS summit: 2015 Ufa declaration. http://www.brics.utoronto.ca/docs/150709-ufa-declaration_en.html

BRICS Information Centre. (2016). 8th BRICS summit: Goa declaration. http://www.brics.utoronto.ca/docs/161016-goa.html

BRICS Information Centre. (2017). BRICS leaders Xiamen declaration. http://www.brics.utoronto.ca/docs/170904-xiamen.html

BRICS Information Centre. (2018). 10th BRICS summit Johannesburg declaration. http://www.brics.utoronto.ca/docs/180726-johannesburg.html

G20 Information Centre. (2009). The G20 Pittsburgh summit commitments. https://g20.utoronto.ca/analysis/commitments-09-pittsburgh.html

G20 Seoul Summit. (2010). The G20 Seoul summit leaders’ declaration November 11-12, 2010. https://g20.utoronto.ca/2010/g20seoul.pdf

International Monetary Fund. (2010). IMF resources and the G-20 summit. https://www.imf.org/external/np/exr/faq/sdrfaqs.htm

Kirton, J. (December 2010). The G20, the G8, the G5 and the role of ascending powers. https://g20.utoronto.ca/biblio/kirton-g20-g8-g5.pdf

Kodabux, A. (2023). BRICS countries’ annual intergovernmental declaration: why does it matter for world politics? Contemporary Politics, 29(4), 403-423.

The Economist. (2009). Not just straw men. https://www.economist.com/international/2009/06/18/not-just-straw-men

World Bank. (2010). World bank reforms voting power, gets $86 billion boost. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2010/04/25/world-bank-reforms-voting-power-gets-86-billion-boost

The BRICS currency conundrum: Weighing the pros and cons of a unified monetary system

Angelovska, M. & Valentinčič, A. (2020). Determinants of cash holdings in private firms: the case of the Slovenian SMEs. Economic and Business Review, 22(1)1-16.

Bharat, A., Gautam, R. S. & Rastogi, S. (March 2024). Trends of currencies in forex reserves: whither de-dollarization? In 2024 International Conference on Automation and Computation (AUTOCOM) (563-568).

Bricout, A., Slade, R., Staffell, I. & Halttunen, K. (2022). From the geopolitics of oil and gas to the geopolitics of the energy transition: Is there a role for European supermajors? Energy Research & Social Science, 88, 102634.

Bhorat, H., Lilenstein, K., Oosthuizen, M. & Thornton, A. (2020). Structural transformation, inequality, and inclusive growth in South Africa (No. 2020/50). WIDER working paper.

Batista Jr, P.N. (2021). The BRICS and the financing mechanisms they created. Anthem Press.

Cheng, P. (2023). Decoding the rise of Central Bank Digital Currency in China: designs, problems, and prospects. Journal of Banking Regulation, 24(2), 156-170.

Cardoso, F.H. & Faletto, E. (2024). Dependency and development in Latin America. University of California Press.

Castells, M. (2020). The information city, the new economy, and the network society. The information society reader (150-164).

Frankema, E. (2024). From the Great Divergence to South–South Divergence: New comparative horizons in global economic history. Journal of Economic Surveys. 2-29

Harriss, J., Jeffrey, C. & Brown, T. (2020). India: continuity and change in the twenty-first century. London. John Wiley & Sons.

Irwin, D. A. (2024). Does trade reform promote economic growth? A review of recent evidence. The World Bank Research Observer, p.lkae003.

Kondratov, D. I. (2021). Internationalization of the currencies of BRICS countries. Herald of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 91, 37-50.

Kumar, B., Ghai, R., Tyagi, M. & Gupta, R. (January 2020). Leveraging technology for robust financial facilities: A comparative assessment of BRICS nations. In 2020 International Conference on Computation, Automation and Knowledge Management (ICCAKM) (pp. 481-486). IEEE.

Kondratov, D. I. (2021). Internationalization of the currencies of BRICS countries. Herald of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 91, 37-50.

Liu, Z. Z. & Papa, M. (2022). Can BRICS de-dollarize the global financial system? Cambridge University Press.

Lukonga, I. (2023). Monetary policy implications of central bank digital currencies. International Monetary Fund. Working paper, (2023/060).

Larionova, M. & Shelepov, A. (2022). BRICS, G20 and global economic governance reform. International Political Science Review, 43(4) 512-530.

Lu, X., Zhang, S., Xing, J., Wang, Y., Chen, W., Ding, D., Wu, Y., Wang, et al. (2020). Progress of air pollution control in China and its challenges and opportunities in the ecological civilization era. Engineering, 6(12) 1423-1431.

Petrone, F. (2022). The future of global governance after the pandemic crisis: what challenges will the BRICS face? International Politics, 59(2) 244-259.

Pierret, L. & Howarth, D. (2023). Moral hazard, central bankers and banking union: professional dissensus and the politics of European financial system stability. Journal of European Integration, 45(1) 15-41.

Roberts, P. (2022). Introduction: Chinese Economic Statecraft from 1978 to 1989: The First Decade of Deng Xiaoping’s Reforms. In Chinese Economic Statecraft from 1978 to 1989: The First Decade of Deng Xiaoping’s Reforms (1-32). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore.

Sindane, J. A. (2020). Has democracy helped or harmed South Africa’s fight against poverty and inequality? University of Johannesburg (South Africa).

Singh, R. (2023). Russia, India, and China Alliance – Towards balancing the World Order. Indo-Asian Geopolitics: Contemporary Perspectives by DRaS, p.111.

Singh, T. (2023). The sustainability of current account in the BRICS countries depends on economic policies’ support to structural adaptation. Journal of Policy Modeling, 45(3) 570-591

Zhuravskaya, E., Guriev, S. & Markevich, A. (2024). New Russian economic history. Journal of Economic Literature, 62(1) 47-114.

Zharikov, M. V. (2023). The international investment position of the BRICS. Humanities and Social Sciences, 16(3)354-365

About the authors

Ndzalama Mathebula

Ndzalama Mathebula is an Assistant Lecturer at the Department of Politics and International Relations, University of Johannesburg. She’s also a PhD candidate at the Wits School of Governance. Her key research niches are international law, political risk, energy, political economy and IR. She writes in her capacity.

Adeelah Kodabux

Dr. Adeelah Kodabux is Director of LEDA, a research and advocacy organisation based in Mauritius, which focuses on enhancing data analyses related to African governance. She co-founded the Centre for African Smart Public Value Governance (C4SP). She graduated from Middlesex University London in 2020 with a PhD in International Relations. Her doctoral thesis is entitled ‘BRICS conversion of common sense into good sense: the relevance of a neo-Gramscian study for inclusive International Relations’.

Makgamatha Mpho Gift

Mr. Makgamatha Mpho Gift is a Senior Researcher for Research and Policy Development at the South African BRICS Youth Association (SABYA) and a lecturer in the Department of Development Planning at the University of Limpopo (South Africa). He is currently finalising his PhD in Development Planning and holds a Master's degree in Development Planning and Management from the University of Limpopo.