Summary

- After the cancellation of debts of developing countries in the early 2000s, a proliferation of new creditors emerged as African countries began entering capital markets.

- The share of traditional and relatively new creditors in African external debt varies a lot across African countries. In 2019, 8 African countries accounted for over 80% of private creditors debt whereas 3 countries accounted for 50% of China’s debt.

- Majority of infrastructure investments are delivered through the use of Public-Private-Partnerships (PPPs) that have been shown to pose serious economic and social risks.

- The absence of a successful sovereign debt resolution system involving all creditors means that the resolutions fall short of supporting recovery for African countries, particularly in light of the evolution of debt profiles.

Introduction

Concerns around the rising debt accumulation patterns of African countries were growing even before the COVID-19 pandemic. Since 2010, public debts have been rising alongside a dramatic shift in the composition of debt stock itself, where shares are increasingly owed to emerging economies, particularly China, and to private creditors through the use of Eurobonds. As of April 2020, the IMF categorized seven African countries as being in debt distress, whilst identifying twelve more that were at high risk of becoming so.

This policy brief focuses on the nature of debt sustainability in Africa and seeks to identify the drivers of financialization in development finance. In addition, we investigate how the slow reform of global finance architecture after the 2008 crash contributed to these debt vulnerabilities, as well as how effective the efforts of current debt relief initiatives are in addressing them.

It is not all about COVID-19

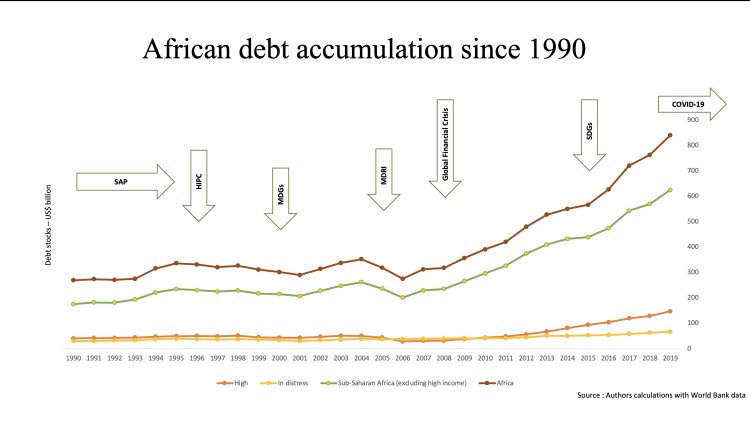

After the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries Initiative (HIPC) and Multilateral Debt Relief Initiatives (MDRI) cancelled most of the debts owed to traditional creditors in 2006, African countries began issuing bonds in international credit markets and procuring new debts. As illustrated in figure 1, African debt levels increased by nearly 140% to USD 841 billion over a 10-year period (2009 – 2019).

Figure 1: Debt accumulation trends since 1990

Since 2011, 75% of Sub-Saharan African countries’ debt servicing has been disbursed to bondholders and commercial lenders, with disbursed amounts corresponding to significant portions of their national revenues. Currently, external debts amount to up to 80% of the Gross National Income for a number of African countries. According to data from 2019, even countries currently considered as being at low risk of debt unsustainability have external debts as high as 41% of their national income and spend significant amounts of their budgets on servicing this. According to data compiled by Jubilee in 2019, Angola spent around 43% of its total revenue servicing its debt, while Ghana spent 39%. Fears around debt unsustainability are increasingly palpable considering the weak domestic resource mobilization and small tax base across African countries.

African countries entered the COVID-19 pandemic period with significant debts owed to both traditional creditors like the IMF and relatively new creditors like China, the Arab Gulf States, and private creditors. The pandemic produced exogenously detrimental effects on the economy which in turn complicated their ability to repay debts. In 2020, the Sub-Saharan Africa region experienced its first recession in half a century with a GDP decline of up to 2.1%. Furthermore, financial flows such as foreign direct investment (FDI), portfolio investments, remittances, and official development assistance (ODA) plummeted. According to the African Development Bank, FDI flows declined by 18% from about USD 45 billion in 2019 to USD 37 billion in 2020. According to the AfDB, the average debt-to-GDP ratio is already expected to increase to over 70% in 2021, up from 60% in 2019. With fiscal deficits doubling to reach a historical high of 8.4% of GDP in 2020, COVID-19’s consequences for Africa’s debts may be dire. Defaulting on loans can have serious consequences for African economies.

The multiplication of creditors in the African debt landscape

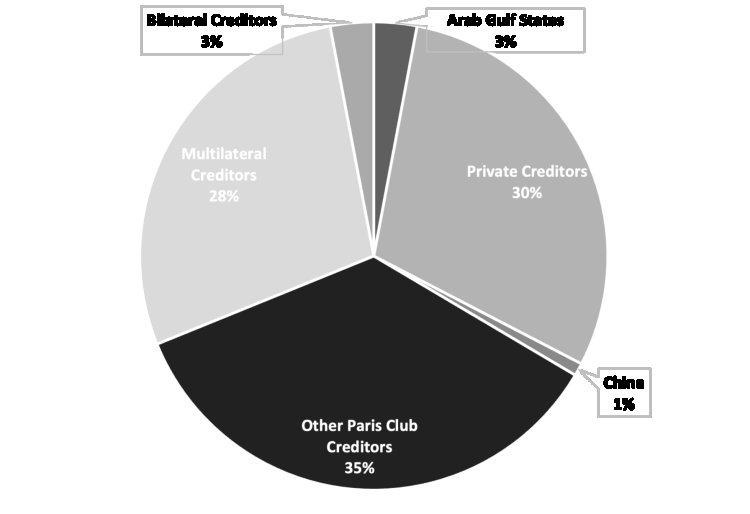

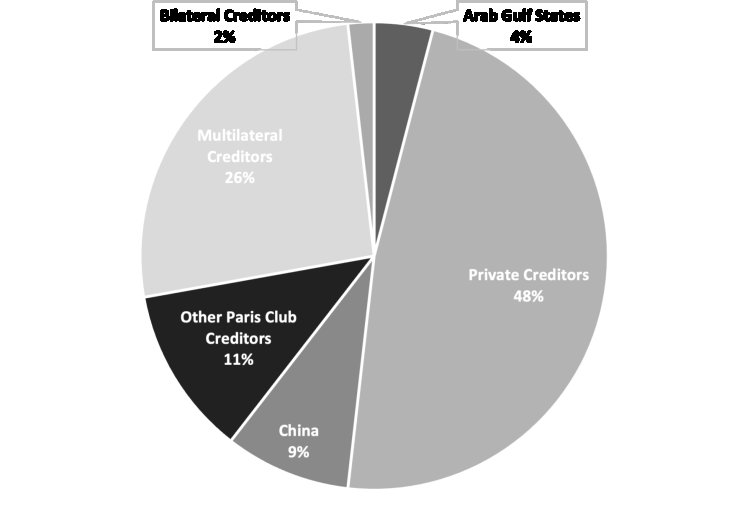

After the cancellation of debts of developing countries in the early 2000s, a proliferation of new creditors emerged as African countries began entering capital markets. Sovereign bondholders accounted for 20% of the continent’s external debt at the end of 2019, with 9% belonging to China and 4% to the Arab Gulf States. Traditional agents saw their spaces shrink, such as the Paris Club (by 11% excluding China), the World Bank (IDA and IBRD) (by 11%), the African Development Bank (by 5%), and the IMF (by 5%).

Figure 2: Breakdown of African Debt by Creditors

While figures clearly demonstrate the growth of creditors’ shares in African external debt, they vary between countries. According to the World Bank Database, in 2019, 8 African countries accounted for over 80% of private creditors debt - including South Africa, Egypt, Nigeria, Morocco, and Angola – whereas 3 countries accounted for 50% of China’s debt – Angola, Ethiopia, and Kenya.

Emergence of private creditors at the onset of the global financial crisis

When the development community embraced the pursuit of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) in 2000, the liberalization promoted by the Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs), gaps between spending and revenue, and the desire to move away from aid prompted governments to pursue financing on capital markets. This saw the emergence of new financial instruments alongside actors making bold claims about reducing poverty. Since the interest rates were relatively low, issuing Eurobonds became an attractive way to raise finance. Although South Africa issued its first Eurobond as far back as 1995, the new Seychelles’ sovereign Eurobond issued in 2006 marked the entry point for many African countries into the international capital markets. Since then, 21 African countries have sold Eurobonds worth USD 136 billion.

As a result, when the Global Financial Crisis hit western countries in 2008, private creditors found a new haven in developing economies. The knock-on effects of this manifested in three major ways: the reduction of remittances, the contraction of capital flows, and the negative shock on terms-of-trade in a high price volatility environment. This resulted in an increase of the risk premiums and interest rates paid by African countries on capital markets, and attracted private lenders looking for higher yields.

Quantitative easing in advanced economies

Quantitative easing programs were introduced in the Global North as part of efforts to mitigate the impact of the 2008 financial crisis. These included direct lending from the European Central Banks and the purchase of bonds by the Federal Reserve. They provided liquidity in developed markets and limited the rise of interest rates. Global liquidity translated into increased foreign currency capital flows for African economies and stimulated the bond issuances of African countries on international capital markets.

Quantitative easing policies have again been intensively implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic by both Western countries and emerging economies like South Africa, Brazil, and India. In 2020, the AFDB also recommended that African countries consider quantitative easing in order to dampen the detrimental economic effects of the pandemic.

Leveraging on private finance for the global infrastructure agenda

The financialization agenda - understood as the global expansion of financial practices across the continent - has seen the emergence of new actors and practices – although unevenly spread out across the continent. This facilitates the intrusion of financial mechanisms and speculative activities into social provision policies, such as the delivery of public goods. The discourse of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) rapidly circumscribed a financialization agenda for infrastructure development. Bridging vast infrastructural deficits has been the core motivation behind African governments’ procurement of debts from international financial institutions (IFIs).

Identified as preconditions for restoring economic growth and achieving SDG’s, the priorities of most governments revolve around investing in and developing transport, energy, health, education and infrastructure. This infrastructure agenda has resonated to such an extent that various international private investors have aimed at providing credit for the various projects brought forward by African governments. A majority of these are delivered through the use of Public-Private-Partnerships (PPPs) that have been shown to pose serious economic and social risks. Although Sub-Saharan Africa’s volume of PPP projects is limited compared to other regions, investments between 1990 and 2018 rose to USD 73 billion. While PPPs provide alternative and mixed funding for huge and costly infrastructure projects, they are still an expensive method of financing that largely forces citizens to carry the cost burden through the payment of service fees. PPPs are also very risky, as the inadequacy of domestic regulatory frameworks elicit poor management and planning, unfavorable terms of contract, and generate a lack of transparency or accountability. This frequently leads to the creation of White Elephants and threatens future debt sustainability, as seen in the recent default case generated by aggressive construction policies in Zambia.

African relationships with emerging economies

Compelled by strong competition coming from emerging economies in the search for new resources and markets in Africa, the infrastructure agenda particularly resonated with the multilateral development banks (MDBs) of G20 countries.

China has been the principal bilateral actor in supporting infrastructure projects. Its relationship to the continent is essentially driven by the Belt and Road Initiative, which seeks to “promote the connectivity of Asian, European and African continents” through massive infrastructural development. According to Johns Hopkins University, China’s government, banks, and companies lent some USD 143 billion to African countries between 2000 and 2017. This constitutes 15% of their infrastructure financing over the same period, a figure substantially more than the 3% of multilateral development banks.

Another set of influential players in African infrastructural development through debts include the Gulf Arab states, particularly Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). They have engaged in growth investment and development models as much as they have expanded their political influence in the continent, principally in the Horn of Africa.

A key issue with loans emerging from these new actors involves a lack of transparency in terms of agreements, making it difficult to evaluate the effectiveness and affordability of debt or investments for African countries.

Nevertheless, it is important to note that African governments have provided nearly half of their own infrastructural development funds over this period and have made individual efforts to drive their own development, as seen in Agenda 2063. These ambitious infrastructure projects will require significant financing in the context of economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. This will either hamper the achievement of the plan's objectives or spur African countries into procuring more debt.

Are current debt relief initiatives adequate for the new African debt landscape?

African countries need funds to support their shrinking economies, equip neglected and precarious healthcare systems, and to service debts in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. The abiding problem is the limited scope for restructuring debt that resembles the early-to mid-2000s MDRI. The mélange of private and non-traditional creditors of the African debt landscape makes creditor coordination difficult. Furthermore, the countries that might spearhead debt restructuring for African countries are themselves battling with the economic ravages of the pandemic.

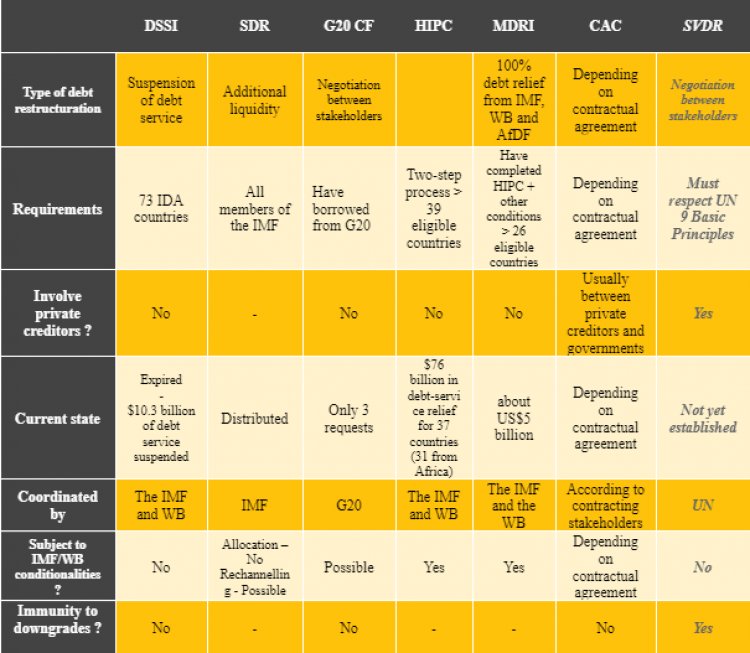

The international community has mustered various measures to support global economic recovery. Although such efforts are noteworthy, the absence of a successful sovereign debt resolution system involving all creditors means that the resolutions fall short of supporting recovery for African countries, particularly in light of the evolution of debt profiles.

Table 1: Comparison of Debt Relief Initiatives

Heavily Indebted Poor Countries Initiative (HIPC) and Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (MDRI)

The Heavily Indebted Poor Countries Initiative (HIPC) was launched in 1996 (and later supplemented by the Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (MDRI) in 2005) to totally relieve the debts of the World Bank and the African Development Fund (AfDF). To date, the HIPC has been approved for 37 countries (of which 32 are African) and provided more than USD 100 billion. Although such initiatives are laudable, their processes do not represent adequate or efficient debt relief measures. To qualify for the HIPC, indebted countries have to meet a variety of strict requirements that prove their eligibility. In addition, they are required to implement structural adjustment conditionalities.

Paris Club

The Paris Club is composed of 22 permanent members including OECD countries, Brazil, Russia, South Africa, official bilateral creditors and observers from international financial institutions. Since its creation in 1956, it has signed 476 agreements with 100 different countries covering over USD 611 billion. Debtor countries only have the opportunity to renegotiate their debts upon reaching an agreement with the IMF. The Paris club only engages in debts issued or guaranteed to a sovereign borrower by a sovereign creditor. Nevertheless, the Club’s treatment of loans procured from China remains unclear., and these form significant portions of African countries' debts.

COVID-19 and Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI)

This initiative was launched by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund in May 2020 to provide fiscal space and financial resources for countries to meet urgent needs emerging from COVID-19. The DSSI only allows a temporary suspension of debt service owed to official bilateral creditors and some non-traditional official creditors, including China. It focuses exclusively on IDA countries. Regrettably, this initiative failed to include private creditors. The payment suspension only covered around 10% of DSSI-eligible countries’ total external debt service for 2020 (although it was extended through December 2021). Furthermore, fears of future credit rating downgrades discouraged many African countries from applying to measures that they would otherwise have benefited from. As we enter 2022, the debt service accumulated throughout the two-year suspensions resume in conjunction with any other supplementary loans that were borrowed during that time.

The G20 Common Framework for Debt Treatments

The Common Framework was initiated by the Paris Club alongside G20 Countries to target debt restructurings on a case-by-case basis should they be requested by any of the 73 countries eligible for DSSI. Unfortunately, this approach excludes many MICs who were severely impacted by the pandemic. Chad was the first country to seek debt restructuring under the Common Framework in April 2021. Ethiopia and Zambia have since followed suit.

The USD 650 Billion allocation of Special Drawing Rights

In August 2021, the International Monetary Fund announced a USD 650 billion Special Drawing Rights (SDR) allocation, the largest in history. The liquidity injected into the global economic system is expected to support countries in their recovery from the COVID-19 crisis. This will generate additional policy and fiscal space, as developing countries in particular will be helped to reduce their reliance on domestic and external debt. However, only approximately USD 34 billion of the USD 650 billion SDR has been allocated to African countries, compared to the USD 434 billion reserved for high income countries that suffered far less economic impact from the COVID-19 pandemic.

The IMF suggests a voluntary channeling of SDRs through its Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust in order to reduce the allocation gap. It provides the Resilience and Sustainability Trust and concessional loans tied to conditionalities . Another possibility could be to channel SDRs to support lending by multilateral development banks. Considering its size and prospective conditionalities, Special Drawing Rights falls short of addressing its objective of providing fiscal space.

Looking toward the future

African countries restructured their external debt 60 times between 1950 and 2017. They reached 149 agreements with the Paris Club and restructured their domestic debt at least 18 times since 1980. Since traditional measures may not effectively address the new African debt landscape, there is a compelling need for new initiatives from the continent that consider the specificities of African economies and allow the equal and transparent participation of developing countries in its processes. There is a need for statutory and human rights based sovereign debt mechanisms to revolutionize international financial architecture. Current contractual methods, generally Collective Clauses Actions (CACs), do not adequately resolve challenges caused by creditor coordination, free-riding, or perverse incentives. Therefore, a statutory Sovereign Debt Restructuring mechanism capable of binding participants to the restructuring process should be put in place.

Incorporating transparency, accountability and governance principles

Any debt mechanism should be guided by the principles of transparency, accountability, and governance, such as those recommended by AFRODAD's African Borrowing Charter which advises that public debt and guarantees be approved by parliament before contracts are signed. Appropriate legal frameworks should be in place and citizens should be well informed so that they can be equipped to monitor the performance of loans.

Including private creditors in traditional debt relief mechanism

The growing concentration of debt owed to private creditors across the financial landscape of developing countries makes the inclusion of private investors in any debt relief measure critical. If not, liberated funds will be diverted to reimburse private creditors instead of being reinjected into the countries’ economy. HIPC and other debt relief initiatives do not prevent private creditors from using legal mechanisms to enforce their credit claims, as demonstrated by the proliferation of litigation with vulture funds. Instead of being invested directly into social safety nets or the health sector, nearly 50% of the IMF’s 2020 COVID-19 loans to the world’s poorest countries (USD 42.9 billion) were used to pay private creditors in the middle of a deadly pandemic.

Furthermore, private creditors that hold commercial debts have not been willing to participate in debt relief. Since they are the continent’s largest lenders, their non-participation implies that governments may have to utilize debt service relief funds to finance private credit. For the DSSI to be more effective in lessening debt burdens and helping countries fight the COVID-19 pandemic, the longitudinal effects of the suspension conditions need to be taken into serious consideration. Private creditors also need to take part in the initiative.

Engaging credit rating agencies

Since the 2008 global financial crisis, credit rating agencies have gained incredible influence in capital markets. Credit rating grades are important for Africa's fledgling capital markets and prospects of cheaper access to finance. However, African countries have increasingly received a number of downgrades to their sovereign credit ratings and outlooks since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. This aggravates the economic situation and results either in investors withdrawing their capital or raising the cost of borrowing.

Ethiopia, Pakistan, Cameroon, Senegal, and Côte d’Ivoire were placed under review for downgrade by the Moody’s credit rating agency in May and June 2020 after requesting bilateral debt service suspension from G20 creditors. Fears around the consequences of further downgrades may even discourage African countries from pushing for the very debt restructuring that would ensure fiscal capabilities against COVID-19. Credit ratings should be frozen in times of crisis to limit further damage to macroeconomic conditions, as supported by the Ghanaian Ministry of Finance protests against Moody’s downgrades.

Updating UNCTAD Sovereign Debt Restructuring Mechanism

In 2015, the UN General Assembly adopted the 9 Basic Principles on Sovereign Debt Restructuring Processes. The resolution states that sovereign debt restructuring processes should be guided by the principles of sovereignty, good faith, transparency, impartiality, equitable treatment, sovereign immunity, legitimacy, sustainability, and majority restructuring. It is commendable that this mechanism was established under the auspices of the UN, since it allows for the equal participation of developing countries in its processes.

However, the legal framework introduced by the initial project was non-binding and received very limited political support from Western governments. A legal framework must be advanced where compliance with those principles by creditors and debtors could be enforceable. This could be achieved under arbitration mechanisms such as a Sovereign Debt Tribunal that would ensure greater attention is paid to fairer clauses in bond agreements. Given that most international bonds are held outside the jurisdictions of sovereign debtors, the governmental apparatus of creditor countries should be responsible for curtailing the litigation activities of vulture funds in their respective jurisdictions. In 2015, Belgium passed Anti-Vulture Laws which prevent creditors from disrupting financial flows to debtor countries. This should be emulated, and particular attention should be paid to debt transparency, responsible lending, and borrowing.

Conclusion

The new African debt landscape’s multiplication of creditors has made the coordination of debt relief during times of crisis more difficult. The high amount of debt accumulated since the mid-2000’s HPIC initiatives has been exacerbated by the disastrous social and financial toll of the COVID-19 pandemic. Measures put in place by the international community were once again “too little, too late”. Although there have been some noteworthy efforts such as the new SDR allocation, the absence of statutory and human rights-based sovereign debt mechanisms that involve all creditors hinders any attempt towards addressing the need for reform in the architecture of the current African debt profile.

About the Authors

Aurore Sokpoh

Aurore SOKPOH is an economist, researching African agency in international public finance architecture as part of her second Master in Africa and International Development at the University of Edinburgh. She holds a Certificate in Data, Economics, and Development Policy from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology; a Master’s Degree in Development Economics and a Double Bachelor in Economics and Law, both from the University of Paris Panthéon-Sorbonne.

Nora Chirikure

Nora Chirikure is a research assistant at Africa Policy Research Institute (APRI). Nora holds a B.Sc. in Politics, Philosophy and Economics from the Erasmus University in Rotterdam. She is currently pursuing a M.Sc. in Economics and Management Science at the Humboldt University in Berlin.

Jason Rosario Braganza

Jason Rosario Braganza is a Kenyan Economist with over ten years’ experience working on international development in Africa. Jason has focused his work over the past decade on trade and regional integration; finance for development and tax; illicit financial flows and domestic resource mobilisation; and poverty and inequality. Jason is the Executive Director at The African Forum and Network on Debt and Development (AFRODAD).