Summary

- The pressure for Nigeria to transition to a new energy future is not likely to be prioritized above resolving Nigeria’s economic crisis.

- The policy choices the new government makes before COP 28 will define and shape Nigeria’s energy system and whether it can meet its commitment to net zero by 2060.

- While the former government constructed an elaborate climate and energy transition architecture, from accession to the Paris Climate Agreement in 2017 to the Energy Transition Plan (ETP) in 2022, this architecture is hamstrung by internal inconsistencies and competition among line agencies for control over different policy aspects.

- The intersection of horizontal and vertical pressures on the new government’s proposed policies on energy transition presents it with three policy and implementation options:

- Option 1: Continue with the architecture of the former government, with minor modification and restructured around the priorities of the new government.

- Option 2: Incorporate energy transition into a larger economic recovery program.

- Option 3: Design a bespoke program for bilateral and multilateral partnership.

- The energy transition presents an opportunity to wean Nigeria from petroleum dependency. For Nigeria, this means diversification. For development partners, it largely involves de-fossilization of energy. Both have the same goal: to diversify from fossil fuels. The challenge is to design support in order to align these apparently conflicting priorities of the international community and Nigeria while advancing both.

The Context

Nigeria is navigating at least five transitions—a global digital transition, a political transition, a demographic transition, an energy transition, and a domestic petroleum transition—while also trying to manage an economic crisis. Its petroleum and energy transitions place it on the horns of a dilemma: to travel the familiar, but so far uncompleted, route of developing and diversifying its economy by leveraging its petroleum resources, or to “take the road less traveled” to a renewable-energy and low-carbon future that could make “all the difference”. Whichever path it takes, Nigeria needs the technical, managerial and financial resources of foreign partners to make either or both a reality. The problem is that the countries with the resources have decided that they are no longer financing new, never-ending fossil-fuel projects. Nigeria nevertheless proposed an ETP, launched in 2022, as its pathway to a carbon-neutral future, with gas featuring prominently as a transition fuel. The pressure to transition to a new energy future is not likely to be prioritized above resolving Nigeria’s economic crisis. This is a crisis driven by debt-fueled policies, such as a petroleum subsidy and fixed exchange rates, and exacerbated by rising interest rates and inflation attributable partly to the war in Ukraine. The war has contributed to the debt distress of over 60 countries. Added to those issues is a security crisis, with five of Nigeria’s six geopolitical zones facing insecurity issues. Nigeria’s fractious elites, unable to sustain stable political settlements where shared developmental and policy priorities would enable deep structural reforms, are constantly managing crises and solving for easy fixes. In terms of energy transition, they find it difficult to muster the discipline required for long-term structural reforms.

The Issue: Aligning the Four Ps for an Energy Transition during an Economic Crisis

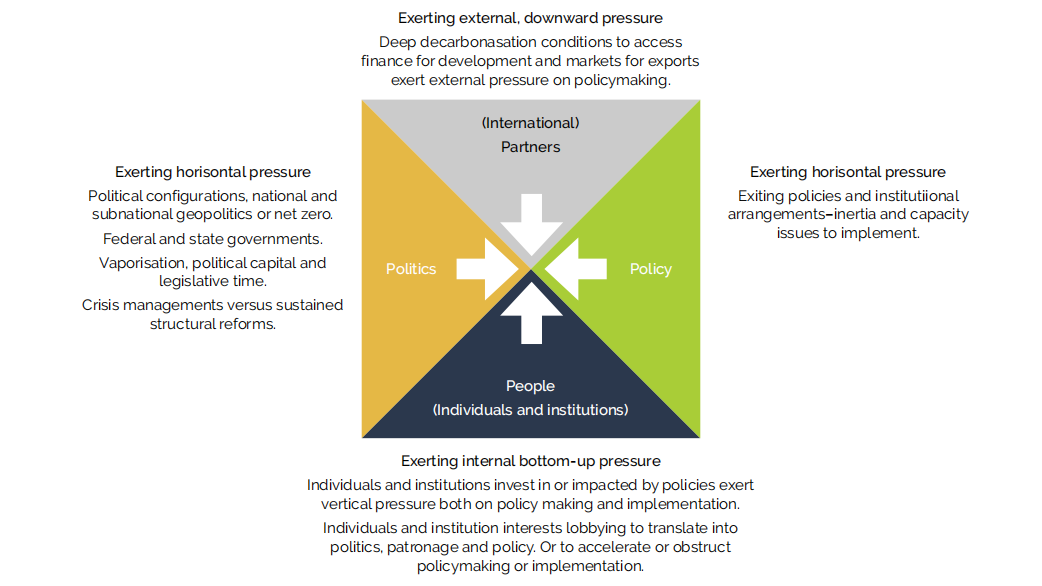

Figure 1 illustrates the intersection of partners, politics, policies and personalities that are the critical components of any energy transition on which Nigeria finally decides. Any policy will be influenced by partners, contested by people, and constrained by politics and policies.

Figure 1: Intersection of vertical and horizontal pressures in energy transition policymaking

Source: Author

The Challenge

Energy as a rigid system involves decades of decision-making for investment decisions—pertaining to infrastructure and regulatory decisions—to come into effect. The prospects of stranded fossil-fuel assets or the obsolescence of certain types of renewable-energy assets are real concerns if long-term investment is to be forthcoming. The 20-year delay between the Nigerian Oil and Gas Policy (2001) and the Petroleum Industry Act (PIA) (2021) produced uncertainty, preventing the long-term investment by petroleum companies that would allow the sector to grow. The current situation of production decline is a consequence of this prolonged uncertainty. Nigeria’s quandary, therefore, is how to come up with a credible and financeable strategy to manage its economic crisis, develop and diversify its economy, and leverage its fossil-fuel resources at a time when partners are relentlessly focused on phasing out or phasing down fossil fuels, and when Nigeria’s own international petroleum partners are divesting and investing in newer, less-challenging petroleum domains.

Put differently, in Nigeria’s peculiar energy and economic circumstances, will the decisions made now, be they fossil fuel-based or renewable, be viable or relevant in 2030? Is the ETP’s USD410 billion cost attached to energy transition economically and technically feasible? Is that cost similar to, or more expensive than, developing the existing fossil-fuel system? Are appropriate policies and regulations in place or in the process of development? Are they consistent across the board and incorporated, or are planned to be incorporated, into all sectors? What are the social costs of transition, and, specifically, how can the petroleum subsidy be removed and the exchange rate be liberalized in a time of a cost-of-living crisis with unsustainable debt? What political and distributional settlements are required to manage disruptions caused by policy changes such as a petroleum removal? The policy choices the Tinubu administration makes before COP28 will define and shape Nigeria’s energy system and whether it can meet its commitment to net zero by 2060. Not all of these questions can be answered in a short policy brief. However, they indicate the potential extent and scope of the issues.

Options and Energy Transition Policy Landscape

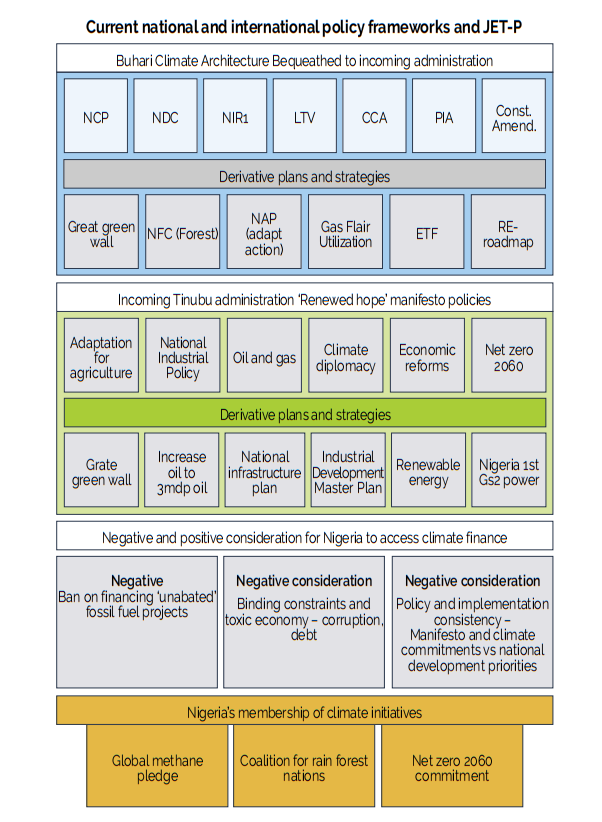

Figure 2 depicts the salient, existing climate-adjacent policy instruments and proposed policies and programs of the new government and includes three of Nigeria’s international commitments.

Figure 2: Current national and international policy framework

Source: Author

The intersection of horizontal and vertical pressures on President Tinubu’s proposed policies with energy transition implications presents the incoming administration with three policy and implementation options:

- Option 1: Continue with the former government’s architecture, with minor modification and restructured around President Tinubu’s priorities; or

- Option 2: Incorporate energy transition into a larger economic recovery program; or

- Option 3: Design a bespoke program for bilateral and multilateral partnerships.

Option 1 presents the allure of continuity. The former president constructed an elaborate climate and energy transition architecture from the time of accession to the Paris Climate Agreement in 2017 up to the ETP in 2022. Though elaborate, this architecture is hamstrung by internal inconsistencies and competition between line agencies for control over different policy aspects. For example, while the ETP relies on gas as a transition or bridging fuel, the Renewable Energy (RE) Roadmap questions the viability of the destination of such a bridge.

Option 2 embeds energy transition into a larger economic recovery plan and presents the most readily implementable alternative—one that integrates energy transition into national development plans. This option would be similar to South Africa’s approach to its Just Energy Transition Partnership (JET-P).

Option 3 has the different allure of designing a new and bespoke set of energy transition interventions that may be more amenable to financing from international partners. The JET-Ps agreed on so far seem to have integrated national development strategies with energy transitions. Nigeria’s ETP is an outlier in terms of bespoke energy transition plans.

Nigeria’s Policy Priorities in respect of Energy

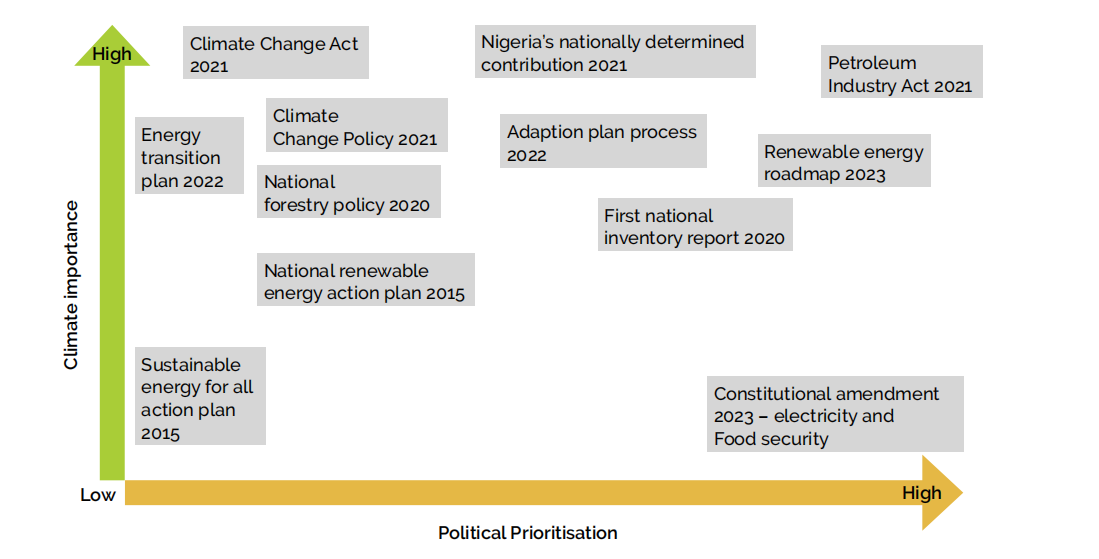

While the former government can be credited with an impressive array of legal and policy tools creating the framework to implement the Paris Agreement, Figure 3 tells a different story of policies that, though constructed within that framework, struggle with internal consistency attributable, at least in part, to narrow institutional or individual interests and agendas. For example, while the PIA of 2021 was a high political priority with great importance for climate change, neither climate change nor the energy transition were incorporated into the law. Yet, for the first time, at COP26, fossil fuels were explicitly blamed for being the main cause of global warming.

Figure 3: Importance and priority of the (climate architecture) signature policy instruments of the former President Buhari administration

Source: Author

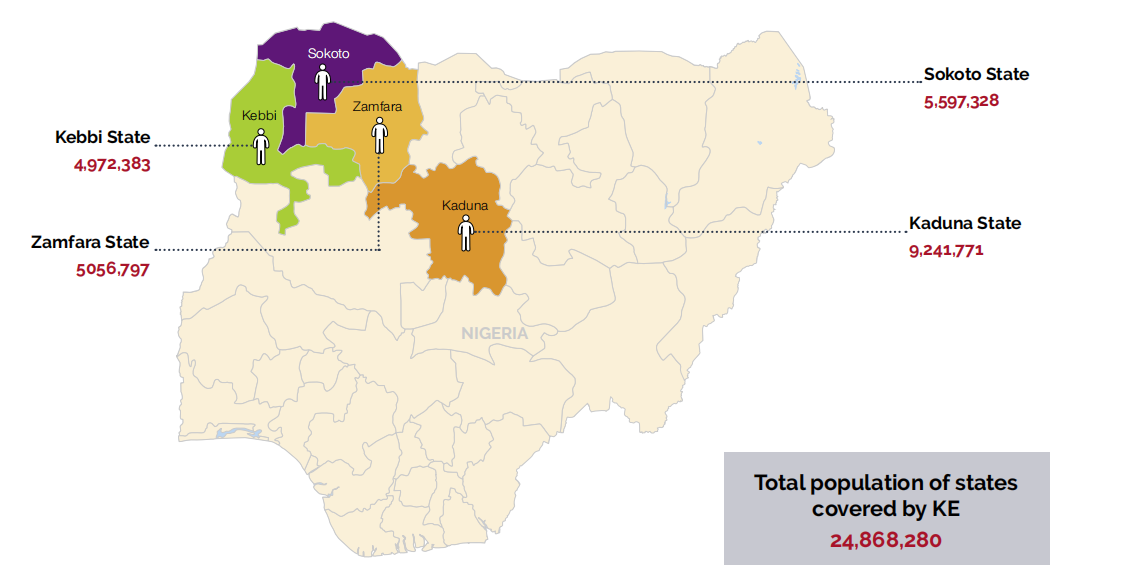

Case Study: The Perils and Pitfalls of Supporting the Devolved Power Sector

The recent devolution of authority over the power sector to state governments provides an illustrative example of a tempting area for development partners to channel resources with the potential for the kind of results experienced under the Power Sector Recovery Programme (PSRP) supported by the World Bank from 2017 to 2020. The performance of the distribution companies and the insights obtained from reviewing headline statistics on the Kaduna Electricity Distribution Company (KE) are sobering reminders of the scale of the problem and the need for methodically tailored interventions that are patiently and diligently pursued in order to achieve desired outcomes. KE serves as an example of the difficulties arising in resolving the complex issues in the power sector and highlights what is needed to fix them. Figure 4 is a map of the states within the KE franchise area, and their respective and aggregate populations.

Figure 4: State populations within the KE franchise area

Source: NBS/EMRC

With nearly 25 million people, the area covered by KE contains over 10% of the country’s population. However, KE has fewer than 900,000 customers, and less than half of its customers are included in the number of total metered customers. Extrapolating from the Baseline Livelihood Surveys conducted by this author for solar projects in the northwestern geopolitical zone, average family sizes vary between 5.8 (in typically monogamous families) and 12 people (in typically polygamous families). An assumed mean household of nine people generates 2.76 million potential metered connections.

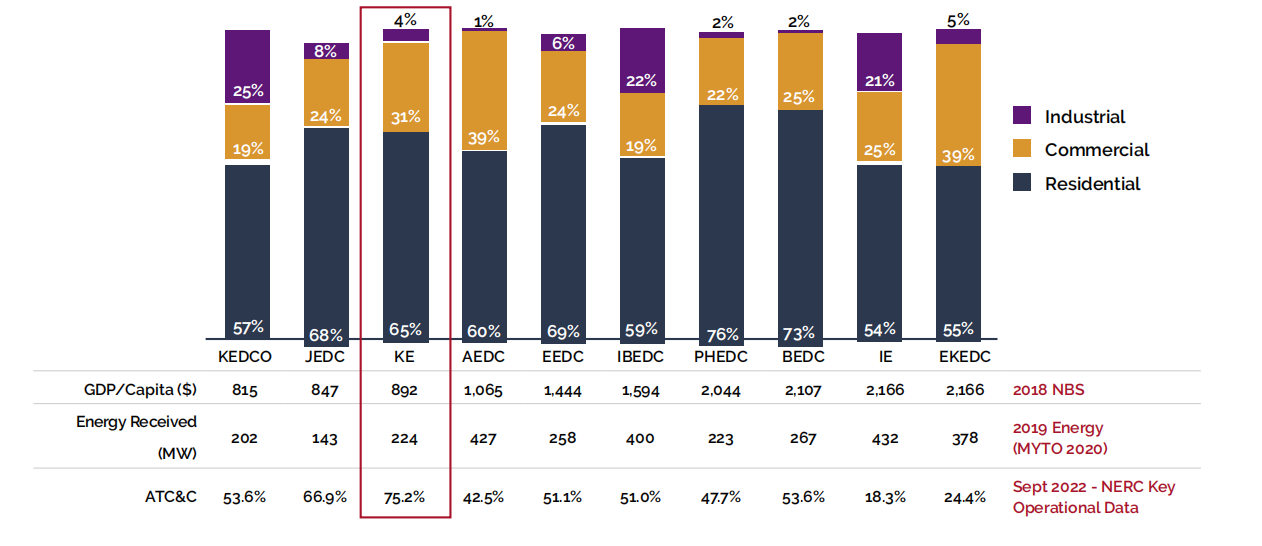

Figure 5 reviews energy consumption by customer group across 10 of the 11 distribution companies in Nigeria. The KE distribution company, with the second-lowest gross domestic product (GDP)/ capita, has the highest losses. Without Kaduna state’s higher per capita GDP, GDP/capita falls below the USD2/day poverty threshold for Zamfara, Sokoto and Kebbi states.

Of the 224 MW received, KE recorded revenues for less than 56 MW due to 75.2% losses. Of that revenue, 65% comes from residential customers, who tend to cost KE the most in terms of supply and who receive subsidized rates. By contrast, the Eko Electricity Distribution Company (EKEDC) managed to reduce its losses to 24.4%. It spent an average of USD 5.2 million in infrastructure upgrades and loss prevention per 1% improvement so as to achieve this level of efficiency.

Figure 5: Electricity Consumption across distribution companies

Source: Author

For the state governments within the franchise area of the KE distribution company, this sum would translate into over USD 250 million just to match the loss reduction the EKEDC has achieved. With some of the highest poverty levels in the country, with two-thirds of KE’s customer base being residential, and with a franchise area that is 200 times larger than that of EKEDC, the task for each state to act, or for the states to act in concert, is herculean. These figures also generate insights into the extent of the task of electrifying Nigeria’s transportation system (electric vehicles), with only Lagos possibly being ready. Finally, they illustrate that loss reduction is the critical precondition to any intervention aiming to improve sector viability. It requires long-term structural reform at commercial and policy levels.

As a result, with the new constitutional amendments, development partners need to truly understand the problem before allocating resources to support interventions. In the devolved power sector, this comprehension means truly understanding the energy gap and distinguishing between the underserved and unserved. It means determining the economic viability of interventions such as metering, and, finally, it means knowing how to prioritize and sequence interventions in a way that the World Bank-funded PSRP and its two main interventions, the Payment Assurance Facility (PAF) with the Central Bank and the Nigeria Electrification Project (NEP) implemented through Rural Electrification Agency (REA), overlooked. The devolved power sector is a largely uncontested policy space that requires a deeper dive into the drivers sustaining the crisis in the power sector. KE presents a window into possible interventions that can be replicated in many other sectors.

Deepening Structural Reforms in “Uncontested” and Less-Contested Policy Spaces

The intersection of politics and policy in the telecommunications, financial, media and tech sectors imperious in the early 2000s allowed a bargain between the commercial, political and bureaucratic elites to be struck to liberalize those sectors. The impulse to channel support to energy transition interventions in the petroleum and power sectors and to federal government agencies, state governments and the more prominent civil society organizations is understandable. That impulse does, however, overlook progress that can be made by casting a wider net of support to incorporate traditional rulers—typically institutions underserved in the federal government—into energy transition-adjacent responsibilities such as those of the National Assembly. Innovative support for subnational entities beyond state governments so as to include traditional rulers, particularly in areas of adaptation and communications, can embed the behavioral change essential to energy transitions at the center of the custodians of culture in Nigeria’s over 300 ethnic and linguistic groups.

Potential Areas of “Uncontested” and Less-Contested Policy Spaces for Exploring Interventions in Nigeria

- Strengthen climate diplomacy: Support Nigeria’s climate and energy diplomacy by developing policy and communications packages to carve out niches related to international advocacy for COP28 consistent with the new government’s approach.

- Provide technical advisory support to the presidency: Support a delivery unit in the Office ofthe President that can include something as basic as organizational design and staffing of the Office; and support the Office of the Secretary to the Government of the Federation regarding the implementation of public-service reform affecting climate action and commitments.

- Place stronger emphasis on backing “investment-grade” energy transition interventions, or at least ones where there is a plausible pathway to financially viable scaling. This emphasis will provide a useful break from the problems of interventions in respect of renewables that have been skewed in favor of vested interests such as some NEP activities. This entails providing support in uncontested policy areas and ministries with high carbon intensity and energy consumption, such as trade and industry, commerce and tourism, and works and housing, while avoiding the politics in petroleum and power.

- Support states: In a handful of states where there may be stronger levels of motivation, integrity of engagement and localized capacity support pilots that may be more effective at scaling than many federal alternatives. This support also implies the necessity of assessing states capable of providing leadership nationally, both in creating a locally conducive environment for energy transition and climate investments and in their ability to provide a beachhead for scaling Nationally.

- Complement interventions by development finance institutions (DFIs): Be ready to work with the DFIs to maximize leverage in critical areas—for example by establishing a strong, common understanding of what is needed to build presidential and subnational commitment to greening the national grid that overcomes existing massive bottlenecks. There should also be shared contingency planning for scenarios where the national grid is clearly not going to advance effectively, together with short- and medium-term responses that might be driven locally.

- Encourage private sector-led interventions that can improve the quality of renewable-energy investment/support by government. Encourage (with technical support) revisiting existing interventions that have stalled at very late stages—notably the public–private partnership on grid renewable energy projects and initial gas flare commercialization projects.

- Promote federal-level interventions conditioned on political will on the part of the president through providing technical leads who can guide a “cross government” approach to energy transition investments and can create the conditions that foster more private interventions. This support might include:

- Technical leads on energy transition evolution across government, with an emphasis on aligning greener energy inputs with economic recovery.

- Technical support for markedly improving the quality and ready access to data required for more effective rural electrification.

- Transaction advisory support with an emphasis on support for initiatives that show clear evidence of economic viability.

- Support consolidating existing progress on a JET-P, with a focus on striking a balance between new renewable investments, gas infrastructure and base-load capacity, and the grid infrastructure that would be needed for this transformation, with the aim to catalyze further investment commitments at COP29 (with introductory work at COP28).

- Plan for contingencies relating to the scenario where government is heavily distracted by economic and political turmoil and there is more productive use of resources reinforcing the private sector, and moving with government when it is more amenable.

Other areas that could also be considered include the following:

- National Assembly: A 70% turnover and new members means that an understanding of climate and energy transition issues is often limited.

- Carbon advice: Increase support for nascent carbon advisory facilities for the private sector wishing to invest in Nigeria (or with environmental, social and governance (ESG) and carbon obligations in the country).

- Data: Increase support for both private and public sector data gathering—with an emphasis on its practical use by energy transition and climate practitioners. Consider warehousing data in easy-to-access portals or links to data sources through a single portal.

- An increased emphasis on viable pilot initiatives that have a pathway to growth in RE-based transport and off-grid generation for productive use. KE case studies demonstrate the scale and scope of the challenge.

- The convening power of elder statespeople and traditional rulers: Directly support elder statespeople and traditional rulers to wield their convening powers to localize energy transition—enhance, amplify and influence behavioral changes required for energy transition to take root in both mitigation and adaptation—and help raise finance to support transition.

Support the Federal Government of Nigeria in Building a Coalition of Support for Financing and Implementing Energy Transition

To build a coalition of support to finance and implement energy transitions, Nigeria will need to marry the opportunities presented in its energy transition plans with the priorities of development partners. Fortunately for Nigeria, global geopolitics of net zero between the Global North, led by America, and the Global East, primarily the Chinese, and now joined by philanthropies, have expanded sources for funding and support.

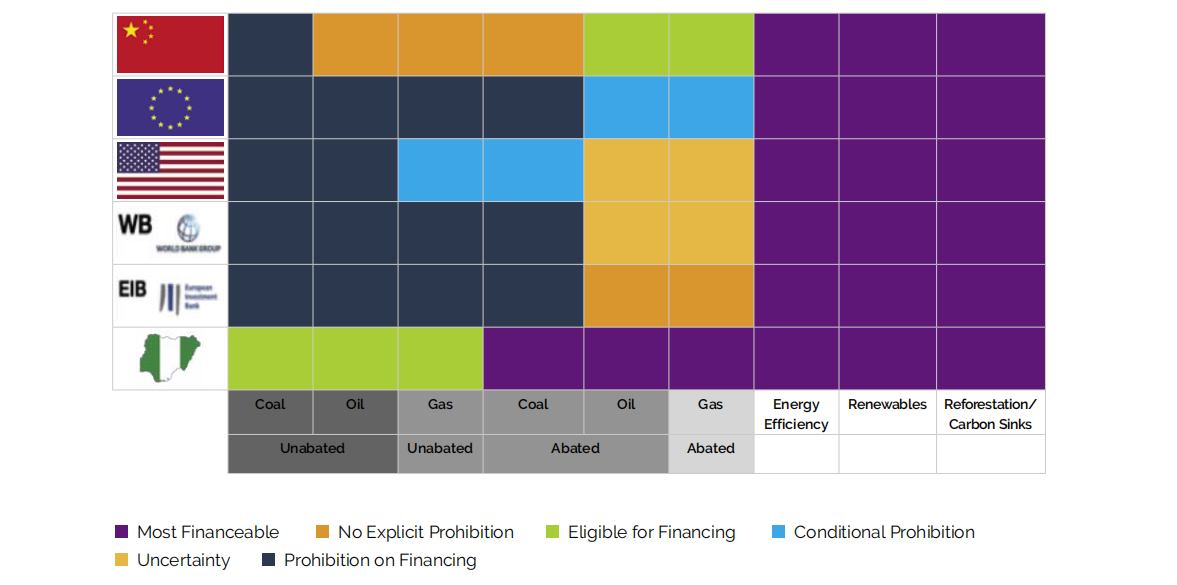

Figure 6 presents a crude traffic-light system of dark or light red, amber and green to illustrate the current financing policy postures of leading potential sources of support and finance for different energy sources. It will be difficult for Nigeria to raise the financing or support to develop its coal resource and to secure financing for new unabated oil or, most importantly, even gas. While China has not formally closed the door on unabated oil and gas, Nigeria faces stiff competition from both new oil-producing countries closer to China and from OPEC (Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries) members such as Saudi Arabia. Though competition is stiff, Nigeria has benefitted from rail, port and information technology infrastructure under China’s Belt & Road Initiative (BRI). Debts incurred under the BRI present obvious opportunities for “climate debt swaps”, as China appears to be softening its position on debt forgiveness. The American-led USD600 billion Global Partnership for Infrastructure and Investment (GPII), though perceived as an attempt to catch up with China’s BRI, presents alternative, non-debt-based funding.

Figure 6: Fueling Nigeria’s energy transition: International partners’ policy postures on financing energy transitions

Source: Author

However, Nigeria’s main export markets for its gas are in Europe. Not only is the European Union (EU) one of Nigeria’s largest development partners, but it is also a member of the GPII. The EU and the European Investment Bank have the strictest policies, placing a moratorium on fossil-fuel investments, threatening to undermine a key plank of Nigeria’s development strategy. Engagement with the EU as part of early climate diplomacy may create the space to both change the tone and reimagine the issue of gas development and limits to, or opportunities for, EU financial investment. Coordinating this diplomacy with domestic policy and following through by delivering on the gas flare commercialization program, and, as a consequence, fulfilling Nigeria’s methane pledge obligations and emissions reductions under its (NDC), may go some way to unlocking “access to capital”. Inevitably, this process entails the new administration coordinating its priorities around access to capital and finance.

Conclusion

Nigeria has been home to policy innovation over the last 20 years. Telecommunications and financial sector liberalization has propelled innovation-enthused sectors, as reflected in their growing contributions to the nation’s GDP. In the petroleum and power sectors, liberalization has proved difficult, as has removing state involvement, including subsidization. The energy transition presents an opportunity to wean Nigeria from petroleum dependency. For Nigeria, this weaning means diversification. For the development partners, it largely involves de-fossilization of energy. Both have the same goal: to diversify from fossil fuels. The challenge is to design support in order to align these apparent conflicting priorities of the international community and Nigeria while advancing both. For Nigeria, expanding the horizon of the future beyond the immediate crisis that consumes its governments, into subtle but substantive areas of uncontested or less-contested policies would present readily moldable hosts for impactful and replicable interventions.

In an environment where policies, personalities and politics intersect, and where policymaking can be fluid, development partners’ prior experiences in Nigeria in designing and implementing projects to support interventions is an advantage. Several projects funded by the United Kingdom Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (UK FCDO), the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and EU/GIZ demonstrate that, where flexibility is built into the intervention, impact and outcomes can be more effective. As the case study of the KE distribution company demonstrates, what may be alluring and compelling may require substantial pre-development support to create the conditions for commercial viability and sustainability. An area that could be of immediate benefit and present a holistic picture of what is pragmatic and possible would be to help the government scope the landscape of support and funding available and the conditions for accessing this funding. A study determining the areas of alignment between Nigeria’s current legal and policy stance with conditionalities would be a useful starting point. This mapping and scoping have yet to be done in Nigeria as part of an energy transition.

About the Author

Najim Animashaun has over 20 years experience in energy sector policy and project management in the public and private sectors, with a focus on governance, institutional reform and the political economy of Nigeria's energy sector. He develops renewable energy projects and is involved in various energy, biotech and fintech start-ups as a sponsor, developer and adviser in Nigeria, Ivory Coast, and Morocco. He has hands-on experience in infrastructure project life-cycle management.