Summary

-

Africa has developed enormously in the last 25 years, but it is facing problems triggered by the COVID-19 crisis and supply-chain interruptions caused by the Russian aggression in Ukraine.

-

The perspective on Africa in Germany is generally skewed: The potential is underrated, and the risks are overrated.

-

When dealing with Africa, the German government should focus more on business opportunities and less on the charity element of development cooperation.

-

The German business community still lacks an entrepreneurial attitude. It is waiting for more government support to engage in Africa. Greater self-assurance would be appropriate and necessary.

-

African governments should minimise or at least increase transparency regarding risks for Western companies and invest in infrastructure on the continent.

Introduction

Despite the enormous progress achieved by many African countries in the last 25 years, the German government does not seem to view the continent and its actors as peers in industrial relations. While several ministries have developed so-called Africa strategies, these mostly focus on classical development policies and only rarely emphasise the economic opportunities offered in many African countries. It is true that German investors have shown great interest in opportunities on the continent, but this has been predominantly in Northern Africa and the relatively more developed South African economy. In addition, the media often fails to present a fair and balanced image of the continent to the German public, reinforcing instead the three Cs: crisis, conflict and corruption.1

This is problematic for three reasons. First, it makes no sense to speak of Africa and not of individual African countries, as the continent is highly diverse. Second, these distorted and undifferentiated perspectives are not in line with the facts. Third, Africa is consequently neglected by the German business community. This negative bias poses problems for both African countries and Germany itself, whose business actors are deterred from engaging in Africa. It is also an obstacle to tackling the challenges imposed by climate change and the latest geopolitical developments.

In this essay, we begin with a brief overview of economic activities and achievements in Africa. We then shed light on German-African industrial relations against the background of the latest developments on the continent. Finally, we briefly describe policy options for governments in Germany and African partner countries, as well as strategies for businesses.

An overview of Africa's industrial performance since the early 2000s

By the first decade of the 2000s, Africa had been the fastest growing continent for almost 20 years. This had to do with both productivity and population growth; the median age in Africa was, and still is, below 20 years. These trends were accompanied by an improvement of governance: Most institutional indicators, including the Human Development Indicator (HDI), Corruption Perception Index (CPI) and the Fraser Institute's Economic Freedom Index (EF) show an improvement during this period.2 In addition, the middle class had grown, and urbanisation was taking place at high speed.3

The diverse experience of African economies since the turn of the century is easily demonstrated by selecting four countries with very different characteristics: Algeria (a large Northern African country), Ethiopia (a large Eastern African country), Rwanda (a small landlocked central Africa country) and South Africa (the largest and most developed economy on the continent). The table below shows the GDP per capita (in inflation adjusted US dollar terms, anchored in 2010) for 2010 and 2022.

| Country | 2010 GDP per capita in USD | 2022 GDP per capita in USD, adjusted for inflation since 2010 |

|---|---|---|

| Algeria | 3291 | 3999 |

| Ethiopia | 445 | 657 |

| Rwanda | 583 | 940 |

| South Africa | 6130 | 6022 |

Data from the World Bank's Open Database available at: https://data.worldbank.org

When adjusted for inflation, the GDPs of South Africa and Algeria did not advance significantly during this period. Meanwhile Ethiopia grew by an average of 8.8% and Rwanda by 6.7% in real per capita terms. The composition of these economies is very different from a sectoral composition. For the purposes of this essay, it is also important to note the variance in the share of manufacturing in exports as well as the manufacturing trade balance. Almost all African economies have annual trade deficits in manufacturing, which reflects the current comparative advantage of these economies. The table below summarises key information about the role of industrial production in these economies.

| Country | Industry value added as a share of total output in 2022 | Industrial output as a share of total exports in 2022 | Ranking on UNIDO's Competitiveness index in 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Algeria | 22.9% | 23.1% | 99th |

| Ethiopia | 6.9% | 16.6% | 143rd |

| Rwanda | 10% | 41.2% | 136th |

| South Africa | 18.5% | 55.1% | 49th |

Data from the United Nations Industrial Development Organisation's (UNIDO) International Yearbook of Industrial Statistics 2023.

Amongst the four countries compared here, Algeria has the largest share of industrial production, at 22.9%. However, industrial production is significantly more important for the export markets in Rwanda and South Africa. Finally, none of these economies are highly competitive measured with the UNIDO's Competitiveness index.

If we take a regional perspective, the 2022 shares of manufacturing in exports are as follows: Europe 78.1% (with Germany at 88.8%), East Asia 94.3%, South-East Asia 82.1% and South Asia 83%. Meanwhile the share for Northern Africa is 45.4%, and for Sub-Saharan Africa 33%. Tunisia, Botswana and Mauritius are African economies with much larger shares of manufacturing in their exports, with 89.6%, 93.3% and 88.4% respectively.

We can see from these data that the ability of the various African economies to export manufactured goods is highly differentiated. This indicates the extent to which engagement with the continent needs to be granular, at least at the country level. It also indicates that countries such as Rwanda and Ethiopia are transforming themselves into vibrant developing nations that offer significant opportunities for trade and business.

International business leaders have noticed the differentiated opportunities on the African continent and expressed their interest in the form of foreign direct investment (FDI). Rwanda, for example, has attracted an average of 2.8% of GDP in net FDI per year since 2010, and Ethiopia even more at an average of 3.1%. Meanwhile South Africa has only attracted 1.8% net FDI per year on average, and Alegria even less at an average of 0.7%.

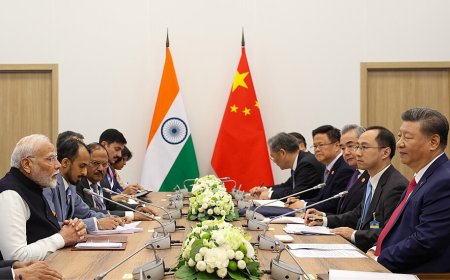

Stakeholders in Africa see Europe as one of a number of potential partners. The latest advances by other players such as China, Russia, the Arab world or India have shown African governments that they have a wide range of options. That said, conversations with different African stakeholders as well as media reports4 give the impression that German companies still have a good reputation as business partners and investors. To harness this potential, German attitudes and behaviour towards African partners should be guided by the new realities.

The share of manufacturing of GDP in Africa has not grown in the last two decades. However, inner-African trade is dominated by manufacturers and is likely to grow once the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) unfolds its full potential. We can also observe an increasing emergence of start-ups, the application of new technologies – often labelled as leap frogging – and a fast-growing service sector. The thriving start-up activity is as impressive as the existence of first-tier firms in growing numbers. African companies are increasingly integrating themselves into global value chains (GVCs).4

On the downside, economic growth in many countries still depends on the export of a limited number of high- and middle-tech goods and services, which makes these countries vulnerable to price shocks. Trade with partners outside of Africa is characterised by the export and import of these commodities. Moreover, after the Covid-19 crisis, prospects in many African countries were poor. Recently, however, most countries seem to be economically back on track. Despite their higher overall economic growth, however, the African Development Bank expressed concern in their 2024 Economic Outlook that sustainable development and social transformation remain elusive on much of the continent, partly due to the slow pace of structural transformation.5 Traditional, low-productivity agriculture and low-skilled labour dominate the structure of these economies. Sustained development will require a transition to higher productivity sectors as well as higher productivity output within traditional sectors.

German-African industrial relations

Several German ministries have formulated Africa strategies which are uncoordinated, if not contradictory. To give an example: Though the Finance Ministry (BMF) and the Ministry of Economic Affairs (BMWK) focus on economic development, they do not discuss the relationship on an equal footing, only as a means to finance German investments in Africa. This paternalistic perspective overlooks the fact that African countries could be important partners in climate policies and, in particular, German hydrogen demand. Even worse, the Ministry of Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) neglects economic relations, focuses on aid and defines its relations with African partners in a very top-down manner. This latter perspective very likely contributes to the biased image and misperception of Africa in Germany.

The foundation of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) has led to the world's largest free trade agreement (FTA), at least with respect to the number of members. Although the AfCFTA has not yet fully utilised its potential, it provides a great opportunity for Africans as well as for workers and businesses elsewhere. This opportunity has not been well understood by Germany's politicians or business community. The Federation of German Industries (the Bundesverband der Deutschen Industrie [BDI]) has recently published a short position paper in which the paternalistic attitude of German officials is rightly lamented.6 However, the industry seems to assign the responsibility for its own entrepreneurial activities in Africa to the government.

Not surprisingly, German companies have been reluctant to operate in Africa, with only about 1,000 out of more than 3 million enterprises pursuing African interests. Nevertheless, German exports to Africa increased between 2000 and 2023 from around USD 10 billion to USD 28.7 billion (around 1.5% of German exports), whereas imports from Africa increased from some USD 12 billion to USD 32.5 billion (2.2% of German imports) in the same period. German exports to Africa comprise machinery (a fifth of German exports), chemistry or other investment goods, and cars (roughly a fourth).7

Between 2010 and 2022, global net FDI to sub-Saharan Africa8 declined from about 2.5% of regional GDP to between 1.5% and 2% of regional GDP. The regional variance is, however, large, with economies such as Nigeria experiencing a net outflow while others such as Mozambique had considerable net positive FDI. In line with this development, German companies do not place much emphasis on the African continent. In 2021, USD 80 billion was invested in Africa, of which half was invested in South Africa, despite the stagnant South African economy. In 2022, this flow fell to USD 45 billion (ignoring the extraordinarily high investment in the Cape). Germany's share of the 2021 surge was USD 15 billion, more than the previous years. German companies traditionally invest close to their customers and do not focus so much on factor prices, at least they do so less in Africa than in, for example, Asia. Since the manufacturing sector in Africa is relatively small, German businesses do not invest a high share of their FDI. What they do invest is focused on North Africa and Southern Africa. Currently, however, several green hydrogen projects on the West African coast are planned by German investors, which would increase the German stock of FDI in Africa substantially.

German business activities are supported by the government through export credit guarantees and investment protection tools. However, export finance for business in Africa is relatively expensive for German companies. At the same time, German banks are highly risk-averse and avoid financing engagements of German firms in Africa. The same holds for investment finance – currently, it seems as if investments are put on hold because interest rates for investment in Africa are too high. To ease the situation, the German government has signed almost 150 bilateral investment protection agreements (IPAs), of which more than 40 have been signed by African countries. The German government makes an IPA conditional for an investment guarantee. As with investments, these guarantees focus on North and Southern Africa. Different programmes, such as Compact with Africa and the Marshall Plan with Africa, are also used to support the activities of German businesses in Africa. The volume of these programmes, however, is relatively small.

In sum, Africa is still not on the radar of German businesses and the German government. This neglect is surprising considering the new geo-economic constellation, demanding a consideration of all potential partners for future economic relations. This is in line with a final observation: German official development aid (ODA) for Africa is not aligned with investment or export promotion and is focused on countries avoided by German businesses. The latter prefer countries with low political risk, whereas ODA is concentrated on those countries with high political risk.9 This mismatch displays a lack of an overall German-Africa strategy.

Policy tools to enhance industrial relations between Germany and the African continent

Principal Considerations

In order to improve the industrial relations between Germany and its African partners, both sides have an array of potential policy instruments at their disposal. These range from general policies to streamlined industrial policy measures.

German policymakers should cover some fundamental geo-economic and geo-political aspects. This implies the acceptance of new realities. Africa no longer waits for proper attention from European partners, who often act as if they want to impose preferences and values on African partners. The Africans also perceive many European countries as dominant and top-down in Africa. While this is not true of the view they have of the Germans, there should still be significant changes in the German attitude towards Africa. First, Africa is very diverse and should be judged country-wise. Second, African partners should be treated as peers when discussing business. Third, the situation demands a renewed development cooperation approach: Aid should be at least partly replaced by trade and investment flows.

African policymakers follow a strategy based on historical ties and economic rationale. For historical reasons, Russia is viewed favourably in some important African countries. In South Africa, for example, the African National Congress government still remembers that Russia — more accurately, the Soviet Union — supported them during apartheid. However, African governments should not judge Russian engagement on the continent as fair treatment on a level-playing field. Russia, like China, follows its own clearly defined geostrategic interests. Solely focussing on relations with these two superpowers will do African countries no good.

That said, the autocracies' engagement in Africa can give African governments some leverage. For example, the Chinese Belt-and-Road Initiative (BRI) should be used as an argument to demand more from Germany, with the focus not lying on ODA, but on business relations. After all, African interests centre on the influx of investment funds and technological know-how. African leaders have been seeking this kind of support for decades. Unlike Russia, Europe or the United States, China answered their call. This is another chance for deeper German-African industrial relations.

In sum, Germany and African countries must face reality and abandon the priors and distorted views they hold of one another. Given the enormous potential, a change in perceptions is vital, even inevitable. It will allow political actors to see clearly the benefits of closer industrial and economic relations.

German economic policy instruments

These general considerations about attitudes and overarching strategies can be complemented with rather mundane industrial policy measures. Economic policy measures can attract domestic and foreign investment and make businesses fit for competition. The ongoing debate about transformation towards a climate-friendly economy in Germany has revealed that African partners and locations have great potential to contribute to this transformation. On the same token, the transition itself calls for more trade and investment between Germany and its African partners.

Africa, in particular the West Coast and the Sahel, can be highly effective in producing green hydrogen not only for Africa itself, but also as an export good to Germany, where it will be needed in great quantities. A few projects have already been planned, and more are needed. However, whether these projects materialise remains to be seen. This potential can be unlocked with the support of the German government. Here, we suggest a few policy measures that are easily implemented and cost effective.

However, whether these projects materialise remains to be seen. This potential can be unlocked with the support of the German government. Here, we suggest a few policy measures that are easily implemented and cost effective.

- Financing projects in Africa is a problem for German companies because many banks perceive country risks in Africa to be high. Finance costs are sometimes prohibitive. This holds for both export financing and investment guarantees. Therefore, we suggest that the German banking sector – including the public banks – develops new business models, allowing for better access to finance for German companies interested in an African engagement.

- We also suggest extending government guarantees for investments in Africa. This can be achieved, for example, by redirecting official development aid funds to such guarantees. There is ample evidence that aid effectiveness is very low across the board.10 This redirection would, therefore, hurt German development actors more than the Africans. Not by chance, African decision-makers call for more business activities on the continent; many even demand to give up or at least significantly reduce ODA.

- The German government should resist making investment in the African continent bureaucratically onerous. The German Supply Chain Act and, more so, the new EU legislation – meant to protect the environment and defend human rights – actually hamper German activities on the African continent. Companies face high costs of reporting and the risk of being taken to court if they are not able to control their full supply chain. Therefore, they hesitate and postpone investment projects in developing countries.11 This is problematic as they already adhere to high standards in Africa, especially when compared to Chinese or Russian firms. As a consequence, there is a danger that companies from autocratic countries with little interest in human rights will fill this gap. European due diligence legislation thereby rather worsens than improves human rights adherence in Africa, not to mention the fact that it seems quite arrogant to assume that African governments do not care about human rights and need lecturing by the Europeans.

- The German government should not try to impose narrow technical standards, e.g. for climate protection, on industry. Instead, it should allow for green technology to be used to produce energy or offer mobility in Germany. The current German government heavily relies on new literature12 suggesting a more focused industrial policy. A closer look reveals that this literature neglects the political economy problems of targeted interventions: Rent-seeking activities distort the effects, which are anyway negligible as governments neither have the information nor the incentives to predict future demand. That said, the German government should allow for more competition and openness, and should less strictly control the domestic economy. Technological neutrality will be more attractive to African regions or countries seeking to collaborate with German companies on climate protection projects.

- Europe should rethink its trade policies towards Africa. Like other industrialised countries, the European Union enforces a number of hidden barriers to African exports such as rules of origin or other behind-the-borders measures, including the notorious Common Agricultural Policy. To enhance relations with Africa, these barriers should be at least partly dismantled.

Foremost, however, it is the business community that is responsible for its relation to other continents. German companies and business associations should develop more entrepreneurial attitudes and a greater appetite for risk. The opportunities in Africa are significant, as entrepreneurs from other countries regularly show. The business community must not fall into the trap of overstating risks and squandering their chances. An emerging African middle class will contribute to the demand for African industrial products, which in turn demands domestic and foreign investment. This requires the export of machinery and other investment goods as well as German FDI. In addition, the envisaged economic transformation requires the stable German import of commodities and a steady supply of green hydrogen. Since German industries compete internationally for these inputs, neglect of their African partners is even more puzzling.

African industrial policy options

Some African governments have learnt the lessons of industrial policy that have emerged over the last two decades. Productive industrial policy is no longer just about inward-looking, protectionist policies, such as the import substitution approaches of the last century. Instead, where industrial policy has been successful, it has been associated with export promotion and an outward-looking perspective.13

In the post-war era, some Asian countries industrialised by developing full domestic supply chains in particular industries, such as shipping, automobiles and electronics. Since then, however, global value chains have also evolved significantly. African countries now have to compete in this context. Industrial policy must help local firms join global, continental and regional value chains by lowering the cost of doing business imposed by bureaucracy, lowering the cost of transport through an efficient logistics system and so on.14 Further examples of useful industrial policy options in the African context include appropriate infrastructure, labour force education and greater access to credit and financial markets.15

One reason for the reluctance of German businesses to invest in Africa is a high perceived risk, which is partly based on misconception, but partly also on real political and economic concerns.16 To attract more investment from Germany, African governments can do much to increase transparency with respect to domestic institutions and governance structures and thereby mitigate the perceived risks.

The lack of infrastructure in Africa is another obstacle to German engagement on the continent. There is a shortage of harbours, airports, railway connections and intra-continental highways. This increases the transaction costs for any business. Investment in this infrastructure will be an excellent use of ODA. At present, foreign companies compare the situation in Africa with other continents, such as Asia, and understandably often make their investments elsewhere.

The concept of infrastructure can be widened and extended to a number of basic business services, such as accounting, tax advice, human relations departments and the like. These are prerequisites for foreign firms either investing in African companies or integrating these companies into GVCs.17 The latter implies that African governments should heavily invest in education. An educated workforce makes FDI in the respective location highly attractive.

Conclusions

Despite some problems occurring after the COVID-19 crisis, the African continent still has enormous potential for the German business community. Whereas some African countries present high political risks, others offer a variety of opportunities. This potential is hidden behind a somewhat undifferentiated German view of Africa as a crisis-ridden continent. Unfortunately, the government is not doing enough to shift these perspectives.

As has become clear, German-African industrial relations suffer from communication problems. German policy actors maintain a paternalistic attitude, and there is low engagement from the business community. Meanwhile, African policymakers lean towards autocratic countries, in particular Russia and China. Both trends are unhelpful for a sober analysis and judgement of the mutual benefits of deeper German-African relations.

In our essay, we have first shed light on the differentiated economic circumstances in Africa and second briefly described German-African industrial relations and the obstacles to a deeper interaction. In the final section, we have derived policy conclusions on a general level and regarding the economic sphere. It turns out that the policies in question require relatively low investment. However, they do require a significant acceptance of these new realities. We strongly recommend that German policymakers and businesspeople adjust their perspectives on Africa.

Endnotes

-

See Freytag, A., and St. Liebing (2020). Mit Afrika auf Augenhöhe zusammenarbeiten. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, October 30, 2020, p. 20 (Die Ordnung der Wirtschaft).

-

See the respective indicators from the UN, Transparency International and Fraser Institute.

-

See e.g. The Economist (2022). China in Africa. Special Report. The Economist, May 28, 2022.

-

See McKinsey Global Institute (2023). Reimagining Economic Growth in Africa. Lagos et al.

-

Available at: https://www.afdb.org/en/knowledge/publications/african-economic-outlook

-

See Statista, www.statista.de

-

The data in this section is from the World Bank's data base: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BX.KLT.DINV.WD.GD.ZS?end=2022&locations=ZG&skipRedirection=true&start=2000&view=chart.

-

See Felbermayr, G., Freytag, A., Tran, L. T. & Yalcin, E. (2019). Instrumente und Wirkung der Außenwirtschaftsförderung in Afrika. Unpublished Report, Jena.

-

See the extensive analyses by Hristos Doucouliagos and Martin Paldam (http://www.martin.paldam.dk/Meta-AEL.php).

-

See Kolev, G. V., & Neligan, A. (2022). Effects of a supply chain regulation: Survey-based results on the expected effects of the German Supply Chains Act (No. 8/2022). IW-Report, as well as Draper, P., Freytag, A., Menter, M. & McDonagh, N. (2023). The Political Economy of Due Diligence Legislation. Adelaide: Institute for International Trade, IIT Policy Brief 21.

-

See for instance Juhász, R., Lane, N. & Rodrik, D. (2024). The new economics of industrial policy, Annual Review of Economics, (forthcoming).

-

This is an important lesson derived from the modern literature on industrial policy by Johász et al (2024), op. cit., footnote 4.

-

See for example: Shepherd, B., and Twum, A. (2018). Review of industrial policy in Rwanda. International Growth Centre. F-38426-RWA-1

-

See for example: Whitfield, L. (2019). Industrial Policy and Development in Africa. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. Retrieved 5 Jun. 2024, from https://oxfordre.com/politics/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228637-e-734.

-

See Felbermayr, G., A. Freytag, Tran, L. T. & Yalcin, E. (2019). Instrumente und Wirkung der Außenwirtschaftsförderung in Afrika. Unpublished Report, Jena.

-

See Draper, P., Freytag, A. & Fricke, S. (2015). The Potential of ACP Countries to Participate in Global and Regional Value Chains: A Mapping of Issues and Challenges. SAIIA Research Report 19, Johannesburg: South African Institute of International Affairs, September 2015.

About the Authors

Andreas Freytag

Dr. Andreas Freytag is Professor of Economics at the Friedrich Schiller University Jena and Honorary Professor at the University of Stellenbosch and a Visiting Professor at the Institute of International Trade in Adelaide.

Stan du Plessis

Prof. Stan du Plessis is a macroeconomist at Stellenbosch University where he is Chief Operating Officer and formerly Dean of the Faculty of Economic and Management Sciences. He is also a Professor in the Department of Economics where he is a specialist in Macroeconomics and Monetary Policy.