Executive Summary

This policy brief is based on the results from Climate Change Adaptation in Nigeria: Strategies, Initiatives and Practices Project, whose aim was to assess existing policies and implementation processes from the perspective of local communities and individuals at the lowest level of decision-making. This policy brief thus presents a summary of Nigeria’s adaptation policy landscape and the stakeholders in the space with key alignments with the adaptation policy frameworks and other economic policy documents. It also presents the gaps, barriers, opportunities and entry points for effective adaptation actions and recommends policy actions that could help to minimise the gaps observed and improve adaptation actions.

Nigeria is witnessing rising cases of climate-related hazards and disasters due to its diverse agro-ecological zones, rapidly growing urban and rural populations, extensive coastline that is vulnerable to sea level rise and storm surges, as well as underlying economic challenges and poor governance. The systemic risks posed by the climate crisis in Nigeria have triggered rising cases of infectious disease outbreaks, frequent communal conflicts, farmer-herder crises, loss of livelihoods, loss of aquatic and terrestrial biota, decreasing food security and rising economic crises. These issues have been exacerbated by a lack of climate finance, especially for sustainable adaptation initiatives, coupled with lack of basic amenities, inadequate infrastructure and inequality.

To mitigate these challenges, the Nigerian government has developed several climate change adaptation and mitigation plans and frameworks, such as the Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC), the National Adaptation Plan Framework (NAPF), the National Strategy and Plan of Action on Climate Change in Nigeria (NASPA-CCN), the Climate Change Act (CCA) and the Medium-Term National Development Plan, to name a few. However, despite having established several adaptation priority sectors in its NDC, NAPF and NASPA-CCN, Nigeria does not have a clear idea of the status of adaptation activities at the local level. There is therefore no clear evaluation of implementation gaps and locally-led processes.

This policy brief, which is based on the results of the ‘Climate Change Adaptation: Strategies, Initiatives and Practices Project in Nigeria’, explores the challenges and opportunities in Nigeria’s climate adaptation space as well as policy implementation gaps, especially as they relate to locally-led adaptation (LLA). It provides extensive insight into the LLA strategies adopted by different communities to address the impacts of climate change on their livelihoods. By taking a deep dive into the adaptation practices of local communities, the paper analyses the status of climate change adaptation policies, strategies, initiatives and practices and highlights opportunities and challenges for deepening locally led adaptation in Nigeria.

The results indicate that LLA strategies are led by local stakeholders who adopt bottom-up, community-driven initiatives which are tailored to their needs, resources and capacities. They build the capacity of local actors to plan and implement adaptation activities and link local and global resources to support adaptation initiatives. This bottom-up approach could unlock the potential and benefits of climate action in Nigeria, especially at the local level, where such actions are urgently needed. Furthermore, the results show that the impacts climate change is having on the Nigerian economy, and the projected increase in the intensity of negative impacts on lives and livelihoods, mean that LLA holds the most promise for far-reaching and sustained solutions. However, public and private sector funding for adaptation falls short of the total amounts needed to tackle the ever-increasing risk of an unfolding climate emergency.

Based on the findings of this paper, the following recommendations are offered on how national, regional and local policymakers and the international community can integrate their resources to develop innovative approaches and solutions to scale up adaptation efforts at local, subnational and national levels:

For local policymakers and stakeholders:

- Raise awareness about climate change impacts and adaptation measures, including co-benefits beyond climate action benefits: Local policymakers and stakeholders need to raise awareness about climate change, its impacts and adaptation measures so that frontline communities in all agro-ecological zones of Nigeria can reduce vulnerability and build resilience against the impacts of climate change.

- Build partnership with local research institutions, private organisations and tertiary institutions for effective climate change adaptation actions: Local research and technical institutions need to partner with local stakeholders, policymakers and frontline communities to build their capacity against climate change impacts. There is also the need to improve the synergy between local policymakers and national and sub-national government research institutions to give frontline communities more agency over adaptation actions.

- Promote ecosystem-based adaptation (EbA) as a sustainable way of reducing vulnerability and building resilience against the impacts of climate change: There is an urgent need for local policymakers and stakeholders to integrate EbA strategies in their climate change adaptation actions by making use of NbSs and ecosystem services. EbA is unique because it is a cost-effective solution that helps communities to conserve and sustainably manage their environments and restore the ecosystem.

- Encourage and support the adoption of climate-smart agricultural practices, such as crop diversification, fish hybridisation and use of drought-resistant and heat-tolerant crop varieties: Local actors should adopt climate-smart agricultural practices to reduce vulnerability and build resilience against the impacts of climate change. These practices improve ecosystems, promote soil health and water conservation, and increase crop and aquaculture productivity.

For the international community:

- Allocate financial resources to support comprehensive climate research and data collection, especially with reference to local and indigenous knowledge, practices and strategies. The international community should seek partnerships with the Nigerian government and local institutions to allocate resources needed to support comprehensive climate research and data collection, which can be used for evidence-based decision-making, risk assessments and adaptation planning.

- Provide concrete and sustained finance in the form of grants to close technology gaps: International actors should assist Nigeria to close its technology gaps in the areas of renewable energy development, fisheries and aquaculture production, forest conservation and environmental protection, by investing in capacity building and making funds available for research in these areas.

- Provide and facilitate the availability and affordability of climate insurance to help vulnerable communities recover from climate-related disasters: The international community should work closely with local, state and federal government agencies and relevant funding agencies to facilitate the availability and affordability of climate insurance which will help vulnerable communities recover from climate-related disasters.

1. Background and Context

1.1 Introduction

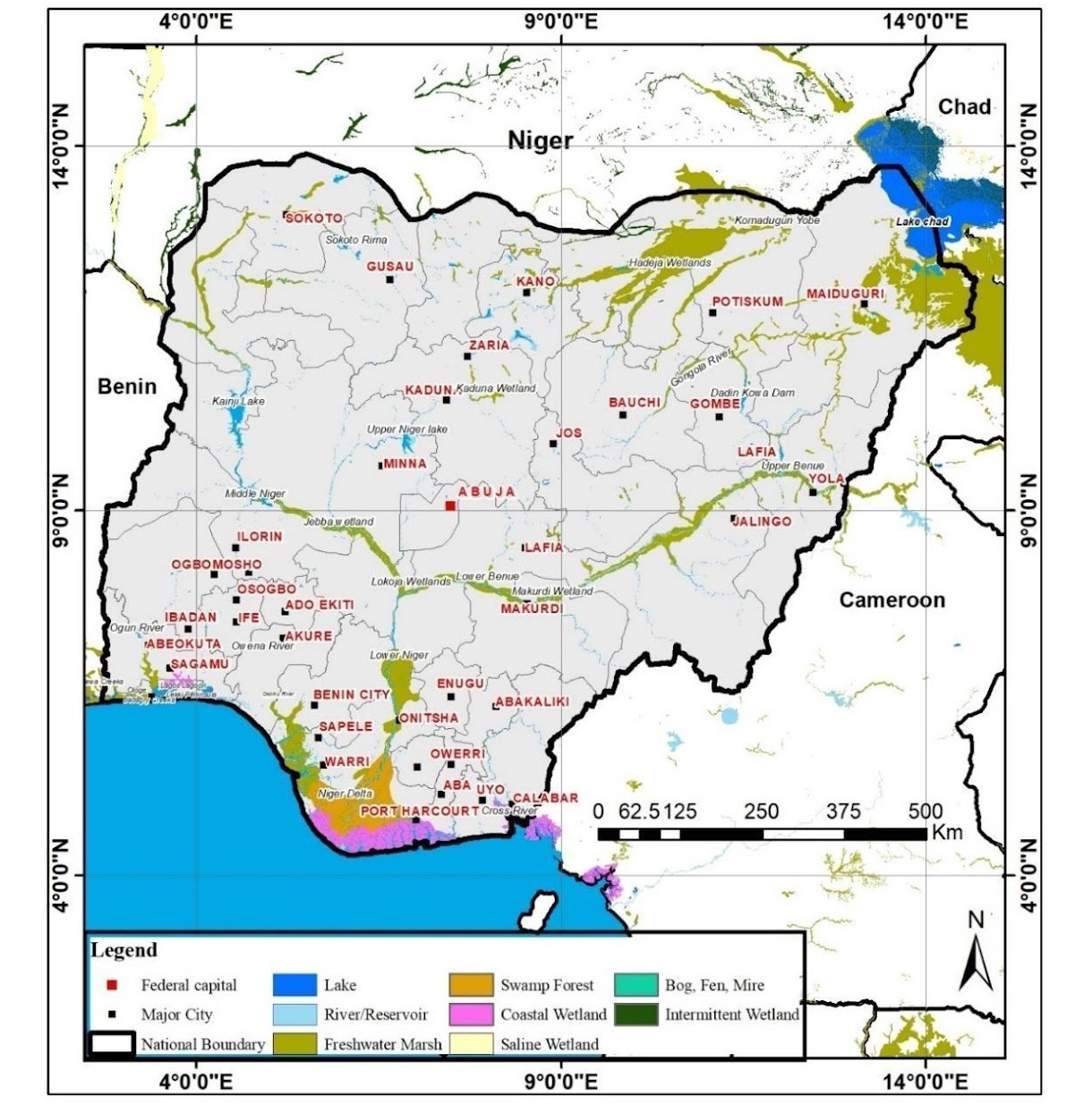

Nigeria is the most populous country in Africa with a total land area of 923,768 sq. km and an extensive coastline of about 853 km.1 This west African country is bordered by Benin, Cameroon, Chad and Niger, and shares maritime borders with Ghana, Equatorial Guinea and Sao Tome and Principe (Fig. 1). The country is made up of 36 autonomous states and the Federal Capital Territory with about 250 different ethnolinguistic groups.As Africa’s largest economy, Nigeria can be classified as a lower-middle-income country with a GDP of US$441.54 billion as of 2021.2

In recent years, Nigeria has witnessed severe macroeconomic instability which has increased the rate of unemployment to about 33.3% with an estimated four in ten Nigerians living below the national poverty line and another 25% vulnerable to poverty.3 Nigeria is also facing several development challenges, including dwindling oil revenues, scarce foreign exchange, ineffective government policies, massive infrastructure gaps and high rates of inequality.

Compounding these effects, climate-related hazards and disasters in the country have doubled in the past two decades, exacerbating inequalities in rural and urban communities, undermining the country’s drive to achieve the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and affecting the federal government’s drive to implement its development policies in line with the Sendai Framework on Disaster Risk Reduction (SFDRR) 2015 – 2030. These effects are intensified by the rising cases of extreme weather events in all agro-ecological zones of the country. The risks posed by these natural events have led to massive food shortages, high infant mortality rates, farmer-herder crises and increasing cases of socio-political unrest.

Figure 1: Physical map of Nigeria (Source: Author)

1.2 Current status of Nigeria: climate change impacts, gaps and opportunities

The African continent has been profoundly affected by climate change with the rate of increase in temperature and its attendant impacts such as loss of biodiversity, coastal erosion, desertification and saltwater intrusion increasing at a faster rate than the global average.4 Accordingly, Nigeria has been ranked by different organisations as highly vulnerable to climate change impacts. For example, Verisk Maplecroft ranked Nigeria as the 7th most vulnerable country in the world.5 Similarly, the Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative (ND-GAIN) in 2021 ranked Nigeria 161st out of 182 countries which were assessed on the basis of vulnerability to climate disasters and adaptive capacities.6 Nigeria has taken some climate actions, including being a signatory to the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015 – 2030 (SFDRR), with a view to strengthening their resilience and adaptation capacity.7 Other actions include Nigeria’s revised NDC, which reveals its recommitment to its unconditional contribution of 20% below business as usual by 2030 and an increase of its conditional contribution from 45% to 47% below business as usual by 2030, provided that sufficient international support is assured.8

Certain factors such as burgeoning urban/rural populations, extensive coastline, limited resources to adequately finance climate actions from public and private-sector entities, and an adaptation knowledge gap have left Nigeria vulnerable to climate impacts. Secondary externalities such as food insecurity, forced migration, conflict and negative health outcomes have increasingly constituted extreme complex barriers to climate action and economic growth.9 Southern Nigeria has experienced erratic weather patterns and high intensity rainfall events leading to recurrent flood disasters, while Northern Nigeria faces droughts and desertification in its arid and semi-arid regions. These two weather extremes have excessively affected the rain-fed agricultural practices of local communities. Disease incidence has been on the rise; vector-borne diseases such as malaria caused about 200,000 deaths in 2021 and amounted to 32% of total global malaria deaths, affecting a total of 60 million Nigerians.10

In a bid to increase its climate change adaptation and mitigation strategies, the Nigerian government has over the years developed several adaptation policy frameworks such as the updated Nationally Determined Contribution 2021 (NDC), the 2021 Climate Change Act, National Climate Change Policy, the National Adaptation Plan (NAP), thee Long-Term Vision (LTV), the Medium-Term National Development Plan (MTNDP), the Biennial Update Report (BUR) and other national and sub-national plans. The National Adaptation Plan Framework (NAPF), which heralded Nigeria’s principal adaptation policy document, is characterised by policies, implementation strategies and practices. The framework also provides a guide for building adaptation practice that is consistent with Nigeria’s economic goals and context. The framework specifically considered community-based adaptation, ecosystem-based adaptation, gender-responsive NAP processes as well as the recognition of climate change as a cross-cutting issue with likely trade-offs and multiple ensuing co-benefits. Furthermore, Nigeria’s current climate adaptation plan utilises a ‘top-down’ approach without including frontline communities and stakeholders in the decision-making process, coupled with their traditional knowledge, cultures, norms and values. Therefore, subnational (state and local) governments need to mainstream locally-led adaptation in their climate adaptation plans and strategies, with the support and collaboration of local and international financial organisations and CSOs, to ensure effective, efficient and equitable delivery of adaptation actions. This will give local communities agency over the design, monitoring and evaluating phases of the adaptation actions.

Locally-led adaptation is a rather new concept advocated for as a valuable ‘bottom-up’ approach to adaptation.11 It is defined as an adaptation approach led by local communities to achieve an equitable, efficient and transparent adaptation. The basic idea behind LLA is that local people are best placed to identify their own needs and vulnerabilities, as well as to make decisions about how to address them. Thus, relying on the knowledge and expertise of local people will help to create solutions that are tailored to the specific needs and challenges of the community.

1.3 Approach and methodology

Against this background, this research project aimed to assess and preview the stories, drivers and barriers of climate change adaptation actions within selected communities in Nigeria and understand how the country’s NDCs and other key policy documents could be effectively implemented through local stakeholders for improved livelihoods and environmental sustainability.

The project adopted a qualitative approach and employed multiple research methods including:

- a comprehensive review of key policy frameworks in a bid to identify gaps, challenges and opportunities of LLA actions;

- an evaluation of the effectiveness of LLA practices in Nigeria and how they can be improved;

- mapping of the NDC as well as other national policy strategies and initiatives, including: adaptation coverage and the consistency or inconsistency of local adaptation policies with the country’s needs, priorities and international development goals and commitments; the state of financing; and the stakeholders involved in the adaptation action space;

- the consultation and engagement of stakeholders at different scales and categories of actors, including: the Federal Ministry of Environment (Department of Climate Change); Climate Change Desk Officers at various Ministries, Departments and Agencies (MDAs); CSOs; NGOs; and international funding agencies, non-governmental agencies, civil society and community representatives, the private sector, etc;

- deep dives of three case studies on local adaptation actions according to key adaptation priority sectors, including energy, fisheries and aquaculture, and land degradation. The deep dives led to the collection of primary data from field observations, focus groups, key informants and relevant stakeholders using several data-collecting tools specifically developed for each case study. The primary data were analysed using the conventional qualitative content analysis method.

2. Mapping Locally-led Adaptation in Nigeria

2.1 Adaptation policy landscape in Nigeria

Nigeria’s Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) was established by ratifying Article 4.2 of the Paris Agreement under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Nigeria submitted its first NDC in 2015 and an updated version in 2021. The updated NDC lacks a well-articulated plan for adaptation; it does, however, contain an adaptation component which focuses on the need to reduce risks that could emanate from the country’s energy and agricultural sectors in the absence of planned adaptation (NAP, 2020). The updated NDC aims to enhance the availability of clean energy for all Nigerians, create green jobs, institute sustainable waste management, provide clean cooking solutions and incorporate gender in all sectors of Nigerian economic development.

While the Nigerian adaptation landscape has several instruments for administering adaptation, the NDC is lacking the desired focus in regard to adaptation. It proposes the following actions to cover its five priority sectors (agriculture, forestry and land use; food security and health; energy and transportation; waste management; and water and sanitation):

- Prioritise capacity development training for federal and state MDAs on gender mainstreaming in policies and programs

- Provide agro-processing and storage facilities to smallholder farmer groups, especially women

- Train women community nurses to address climate change related diseases

- Develop affordable clean cooking options for rural communities and schools

- Mobilise women groups to establish nurseries and plant trees upstream to minimise soil erosion and improve water quality

- Train women in community-based quality monitoring systems and service provisions at the state and rural level, based on valid scientific data

Following the listed actions, the NDC’s proposed adaptation strategies offer insightful domain-specific adaptation plans, broad paths to take and guiding policies and activities. The NDC’s proposed adaptation strategies also offer/identify the responsible entity.

Moreover, in recognition of the burgeoning impacts of climate change in Nigeria, the Federal Government has over the past decade developed several adaptation policy frameworks (APFs), with short- and long-term strategies for the effective management of the climate crisis and the reduction of its impacts on the environment. The majority of these APFs highlight Nigeria’s bold and ambitious plans, actions, goals and strategies for mainstreaming adaptation across all spheres of governance. Some of these policy documents include the updated NAP framework, the National Adaptation Strategy and Plan of Action on Climate Change for Nigeria (NASPA-CCN), the Nigeria Climate Change Policy Response and Strategy (NCCPRS), the Nigeria Climate Change Act (CCA) 2021, the National Climate Change Policy for Nigeria 2021 – 2030 (NCCP), the National Action Plan on Gender and Climate Change for Nigeria (NAPGCC) and other national policy frameworks which have components of adaptation and economic development plans.

An analysis of these policy frameworks shows that the Nigerian government has made concerted efforts to increase adaptation actions in thirteen priority sectors such as agriculture; freshwater resources, coastal water resources and fisheries; forests; biodiversity; health and sanitation; human settlement and housing; energy; transportation and communication; industry and commerce; disaster, migration and security; livelihoods; vulnerable groups; and education. Nigeria’s Adaptation Communication to the UNFCCC (ADCOM), the NASPA-CCN, the NAP framework and the NCCPRS have well-structured adaptation strategies, policies and action plans that cover these thirteen priority areas. Furthermore, a review of the APFs shows that relevant stakeholders were integrated into the adaptation planning process. Some of these stakeholders include the federal, state and local governments; the private sector; civil society organisations (CSOs); households and individuals; and international organisations and donor agencies.

Additionally, Nigeria has numerous stakeholders that play diverse roles in its climate adaptation policy space. The majority of these stakeholders carry out diverse climate change adaptation and mitigation actions at the local level, while a good number of them play crucial roles in climate change policy advocacy at the national and subnational levels. The table below shows a non-exhaustive list of stakeholders working within the adaptation space. It also shows their scale of operation and type (Table 1).

| Name of Organisation | Type | Scale of Operation |

|---|---|---|

| Abuja Environment Protection Board | Government | Sub-National |

| ACI E and Resources Limited | Private | National |

| Africa Finance Corporation | MFI | International |

| African Climate Reporters | Private | International |

| Afrihealth | NGO | International |

| AOA Foundation | NGO | National |

| Banner Centre for Community Transformation | NGO | National |

| Bridge That Gap Initiative | NGO | National |

| Canadian International Development Agency | IDO | International |

| Carbon Limits Limited | Private | National |

| Central Bank of Nigeria | Government | National |

| Centre for Climate Change and Development, AEFUNAI | Academia | International |

| Centre for Climate Renaissance | Government | National |

| Centre for Promotion of Private Sector | Private | National |

| Centre for the Study of the Economies of Africa | Think tank | International |

| Clean Energy | NGO | National |

| Clean Technology Hub, Abuja | NGO | National |

| Climate and Clean air Coalition | NGO | National |

| Climate Tack Podcast | Private | National |

| Climfinance Consulting | Private | National |

| Creative Youth Community Development Initiative | NGO | |

| Crutech Renewable Energy Centre | Think tank | National |

| Department of Climate Change, Federal Ministry of Environment | Government | National |

| DevTrain Community and Entrepreneurship Development Initiative | NGO | National |

| Economic Community of West African States | IDO | International |

| Energy Transition Office | Government | National |

| Environment and Climate Change Amelioration Initiative | NGO | National |

| Environmental Sustainability Research Group | Government | National |

| European Union | IDO | International |

| Evidence Use in Environmental Policymaking in Nigeria (EUEPiN) Project | NGO | National |

| Federal Institute of Industrial Research | Government | National |

| Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development | Government | National |

| Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development | Government | National |

| Federal Ministry of Agriculture, Abuja | Government | National |

| Federal Ministry of Health | Government | National |

| Federal Ministry of Power | Government | National |

| Federal Ministry of Power, Works and Housing | Government | National |

| Federal Ministry of Science and Technology | Government | National |

| Federal Ministry of Transport | Government | National |

| Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) | MFI | International |

| Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office | IDO | International |

| Forest Citizens | NGO | National |

| German Agency for International Cooperation (GIZ) | IDO | International |

| GIVO Africa | NGO | International |

| Global Environment | IDO | International |

| Global Environmental and Weather Solutions | NGO | International |

| Green matters International Limited | NGO | International |

| Health of Mother Earth Foundation (HOMEF) | NGO | National |

| Heinrich Boll Foundation | NGO | International |

| Institute for Public Policy Analysis and Management (IPPAM) | Government | National |

| Institute of Ecology and Environmental studies | Government | National |

| Institute of Food Security, Environmental Resources | Government | National |

| Integrated Institute of Environment and Development, FUPRE | Academia | National |

| International Climate Change Development Initiative | NGO | National |

| International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) | MFI | International |

| NASENI Solar Energy Ltd | Private | National |

| National Automotive Design and Development Council | Government | National |

| National Centre for Energy Research and Development, University of Nigeria Nsukka | Academia | National |

| National Environmental Regulations Enforcement Agency (NESREA) | Government | National |

| National Space Research and Development Agency | Government | National |

| Natural Eco Capital | NGO | National |

| Nextier SPD | Private | International |

| Nigeria Climate Innovation Centre | Government | National |

| Nigeria Incentive-Based Risk Sharing system for Agricultural Lending (NIRSAL) | Government | National |

| Nigeria Television Authority | Government | National |

| Nigerian Economic Summit Group | Government | National |

| Nigerian Environmental Study Action Team (NEST) | Government | National |

| Policy Alert | NGO | National |

| Red stack advisory | Private | National |

| Rocky Mountain Institute | Think tank | International |

| Rural Electrification Agency | Government | National |

| Rural Electrification Agency | Government | National |

| Society for Planet and Prosperity | NGO | National |

| Sustainable Development Solution Network | Think tank | National |

| Sustainable Energy Practitioners Association of Nigeria | Think tank | National |

| The Centre for Research and Development, Federal University of Technology, Akure | Government | National |

| The Green Institute | NGO | International |

| The West African Science Service Centre on Climate Change and Adapted Land Use (WASCAL) | Academia | International |

| United Nations Development Program | IDO | International |

| United States Agency for International Development | IDO | International |

| Voice of Nigeria | Government | National |

| Women Environment Program | NGO | International |

| World Bank | MFI | International |

| World Food Programme (WFP) | IDO | International |

Table 1: Key stakeholders in Nigeria’s climate adaptation landscape (Source: Author’s construct)

Key:

- Think Tank/Academia – An organisation comprising experts that engage in research or provide advice or ideas to shape policy or the discourse on specific topics.

- Private – A privately run organisation that may or may not be a non-profit.

- NGO – Non-Governmental Organisation, defined as a non-profit organisation operating outside of the confines of government and funded in large part by donations and grants.

- Government – A core government agency, funded strictly by government finance appropriation from the relevant legislative body.

- IDO – International Development Organisation, typically an NGO, with an international reach. These are typically funded by governments of developed countries and offer development finance and financial aid to developing countries.

- MFI – Multilateral Financial Institution, an institution that has the mandate by agreements between several countries to distribute ODA from developed to developing nations.

Overall, the mapping processes showed that the policy framework for adaptation in Nigeria is relatively comprehensive and expanding by the day. There are several exemplary attributes of policies including the stated need for adaptation to be iterative, inclusive, flexible and cross-cutting. These are critical in preventing unintended consequences and promoting the likelihood of acceptance by a wide section of stakeholders. Collaboration between relevant agencies in preparing national documents is commendable and has been observed in the preparation of all national adaptation policy documents. If the same level of collaboration is maintained during implementation, it could very easily close the implementation gap and be a best practice. The alignment of policies shows that stakeholders agree on what to be done. However, this isn’t translating into action on the ground. There is a good reason why implementing adaptation policies is difficult: The cost of implementation is substantial and climate action still has to compete for scarce public funds. Furthermore, skilled manpower is not always readily available to allow for the smooth implementation of plans. Nevertheless, local stakeholders have shown considerable resolve in their continued pursuance and promotion of climate action. Their activities show resilience in the face of prevailing gaps and barriers. For example, in many cases local communities have noticed changes in the climate and have been making do by adopting simple practices to address some negative effects.

2.2 Locally-led adaptation: a fitting approach for climate action and socio-economic development in Nigeria

The climate crisis is disproportionately affecting Nigeria and other sub-Saharan African countries, with a marked increase in the frequency and magnitude of hazards and disasters, forced displacement, conflicts and food insecurity. Due to the contextual and geographical conditions as well as need and available resources, locally-led adaptation (LLA) can be an effective, efficient and equitable model of delivering adaptation actions at this level and beyond. According to Coger et al. (2022)12 LLA involves the equitable distribution of power and resources and elevates local innovation and knowledge for more effective resilience-building. LLA’s approach to adaptation is framed to ensure that frontline communities have individual and collective agency over the design, monitoring and evaluation of adaptation actions. Furthermore, LLA takes a ‘whole-of-society’ approach, recognising the importance of traditional knowledge and expertise in reducing climate risks and ensuring that frontline communities and local actors have equitable agency and resources to build resilience. This is particularly important for the socioeconomic development of Nigeria, where over 70 percent of its population is engaged in subsistence agriculture — in 2021, the sector contributed up to 23% of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP). In addition, LLA has the potential to reduce the vulnerability of frontline communities to climate risks given the diverse agro-ecological zones of Nigeria that make the ‘top-down’ approach currently used by the Federal Government ineffective to improve the lives and livelihoods of rural communities and those living in informal settlements.

LLA also presents other potential benefits. It can be a platform for local communities to define their own path in adapting to climate change and create a plan that works best for them, ensuring that solutions are tailored to the needs and priorities of each community. This can be especially important in remote and rural areas, where local knowledge of the environment and climate patterns can be invaluable. Additionally, locally-led adaptation can also play an important role in strengthening the resilience of communities by enabling them to plan, become more aware of the climate risks they face and develop strategies to reduce their vulnerability. This can help to ensure that communities are better prepared for the future impacts of climate change. This last point is essential, because it enables communities to develop their own locally appropriate mitigation and adaptation strategies based on an understanding of the local context. Moreover, LLA could encourage local ownership and participation, which can help to ensure that solutions are implemented in a timely and effective manner. Finally, by taking the lead in the development of adaptation strategies, local communities can become more self-reliant, enhancing their capacity to manage and respond to the impacts of climate change. Indeed, LLA is critical for effective national and global climate actions as it helps countries and the global community to ensure that adaptation efforts are tailored to the specific needs of local communities, and that they are implemented in ways that are culturally, economically and politically appropriate. Therefore, by increasing the number and effectiveness of LLA efforts, national and global climate action can be better informed, more effective and more resilient.

3. Examples of LLA actions in Nigeria

Frontline communities in Nigeria are building resilience against the impacts of climate change by using numerous LLA strategies. Evidence from this research shows that local communities in Nigeria approach adaptation in an organised manner and use several traditional methods specific to their environment to increase their adaptive capacities and build resilience against climate change. While national adaptation strategies feature a great deal of high-level planning and policymaking, adaptation at the local level is usually fast-paced and iterative. Adaptation practices and initiatives of these communities are primarily controlled by different agro-ecological zones, indigenous/traditional knowledge systems and cultural values. These adaptation practices have been going on for decades, albeit at a small-scale. The section below highlights key findings from the three case studies that were undertaken to explore the motivations, strategies, outcomes, challenges, opportunities and entry points for effective and sustainable local adaptation actions.

3.1 Case 1: Biogas production for forest conservation in Nigeria: narratives and voices from Owode smallholder farming communities

Forests in Nigeria control ecosystem services, protect biodiversity, support livelihoods, play a fundamental role in carbon sequestration and contribute to sustainable growth and development. However, Nigeria lost about 1.14 million hectares of forest cover from 2001 to 2021, which is equivalent to 11% decrease in its forest cover since 2000 and equal to 58.5MtCO2e.13 Therefore, in line with Nigeria’s National REDD+ Strategy, several Nigerian communities are integrating Nature-based Solutions (NbSs) in their adaptation strategies to reduce emissions from deforestation and biomass exploitation. To achieve their aims, these communities convert agricultural biomass waste into a renewable source of energy (biogas) to conserve the rapidly depleting forest biomass. A cassava processing centre and several farm settlements in Owode, Ogun State, which are currently facing massive deforestation and energy poverty, have resorted to a few of these initiatives to improve access to sustainable energy (Fig. 2). These farmers, who are mostly women, resort to burning farm wastes and other forms of wastes (e.g., plastic waste) when they run out of fuelwood. The community is currently in the pilot phase of deploying a biogas production facility. Waste generated from cassava processing and livestock and poultry farming is expected to feed into the facility to produce biogas, while the by-products of biogas production will be used to improve soil health and fertility. This is expected to reduce the farmers’ overdependence on energy from forest biomass and help conserve the forest in line with Nigeria’s REDD+ framework. The results obtained from the research show that despite the relative lack of government support to tackle climate change impacts and implement several adaptation actions, farmers, artisans and members of Owode community and its environs are already taking necessary steps toward addressing issues related to energy poverty and environmental degradation.

Figure 2: A cassava processing centre in Owode, Yewa South LGA, Ogun State, Nigeria (Source: Author’s fieldwork)

Figure 3: Firewood-powered earthen stove used by the local women to process cassava flour. (Source: Author’s fieldwork)

The community is motivated by the need to: sustain their means of livelihoods given the high rate of poverty and unemployment in the country and their desire to have access to affordable, efficient, cleaner and sustainable energy sources in line with sustainable development Goals (SDGs) 1 and 7; avert the increasing incidence of climate impacts, especially flooding, environmental pollution and urban heat islands; and improve their health and wellbeing by reducing the negative health outcomes associated with constant exposure to indoor air pollution and heat from fuelwood use, as advocated in SDGs 3.

The practices and strategies employed by the farmers, labourers and artisans living in the community include the use of agricultural biomass waste and residues. For example, they may use: sun-dried seeds/nut shells, cassava peels, corn stover, leaves, roots, crop stalks and forest litter as substitutes for fuelwood to reduce the cost of firewood used in processing cassava into garri; agricultural waste (cassava peel, livestock and poultry waste) for biogas production; and the residue generated from biogas production as green manure to replenish the soil nutrients and control soil/gully erosion.

Their best practices include active collaboration with agricultural research institutions, private organisations and other tertiary institutions within Ogun state on innovative research into the scale-up of clean cooking stoves that significantly reduce emissions and other health risks by using charcoal briquettes. They have also demonstrated a readiness to abandon the use of fuelwood and switch to a cleaner energy source partly because of the negative health outcomes associated with long periods of exposure to the heat and smoke emanating from constant use of firewood.

The main outcomes of the action taken by the local farmers and labourers, in addition to the beneficial outcomes experienced by using biogas as an alternative source of energy, include the opportunity to reverse the negative trend of deforestation, restore biodiversity and improve ecosystem services, thereby enhancing carbon sequestration and reducing the concentration of GHGs (Box 1).

Box 1: Narratives of key informants on the importance of biogas energy on rural livelihoods in Owode community

Key informant 3: Yes, biogas is very important because it is an alternative source of energy which is clean, renewable and has no effect on the environment. Don't talk about carbon monoxide. Hence biogas is important to the community because of rapid population the community has a lot of demand, which has led to loss of biodiversity people get the firewood to make houses and beds where they live so firewood is in scarce supply. So, biogas helps us as an alternative source of energy.

Key informant 4: Biogas is important to our community because of the rapid increase in the population of our community that has placed a lot of demands on firewood, which has led to deforestation I believe that biogas is an important source of energy, which is renewable and has no effect on the environment.

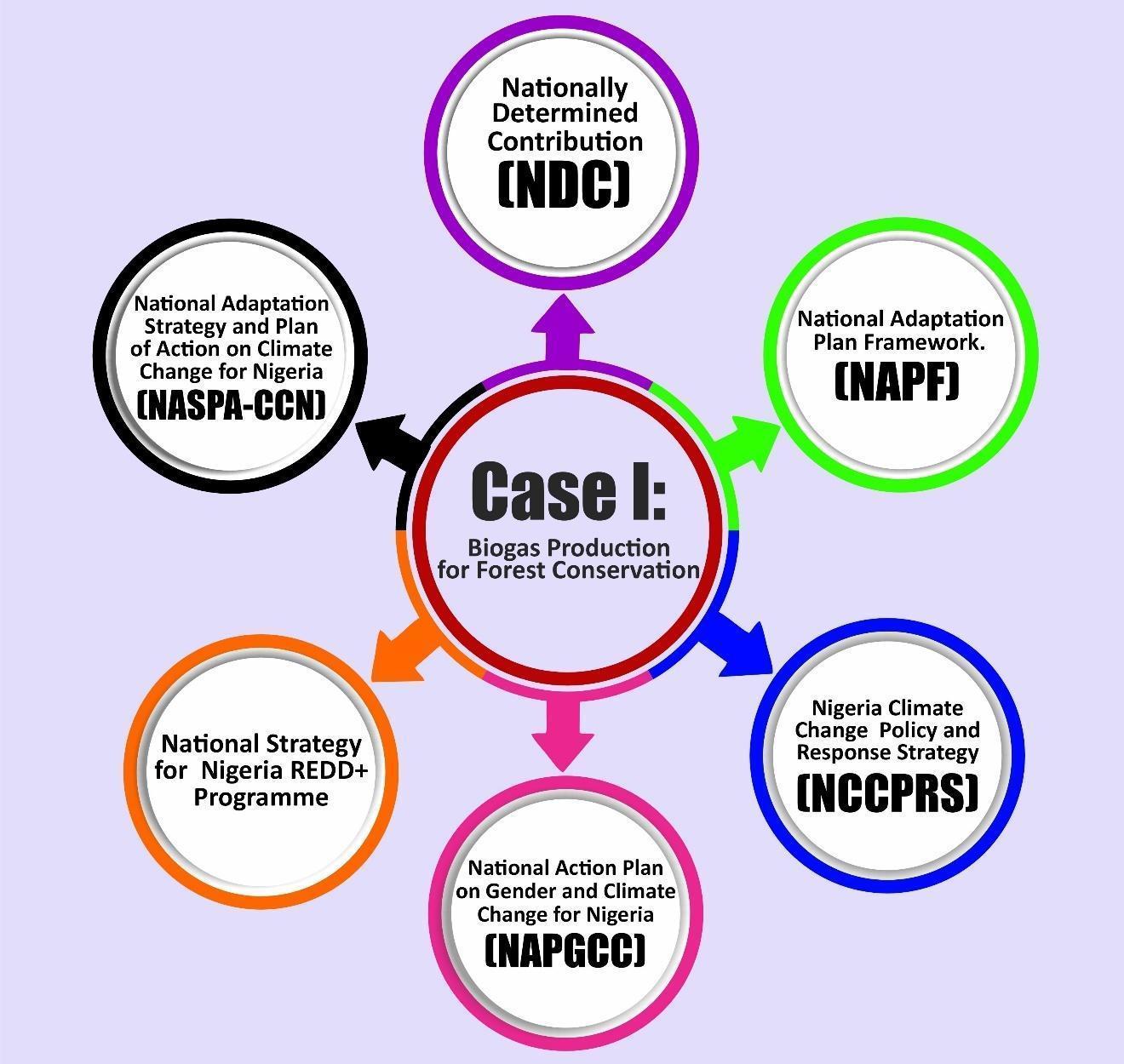

Alignment with NDCs and other national, regional and local policy priorities

The LLA practices and strategies being implemented by the community members are in strong alignment with Nigeria’s NDC and other relevant national policies, strategies and action plans developed to address climate change impacts, natural hazards and disasters, and environmental sustainability (e.g., the Nigeria National Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency Policy (NREEEP), the Nigeria Climate Change Act, and the National Climate Change Policy for 2021 – 2030, to name a few).

Figure 4: Relationship between Case I and national policies and strategies. (Source: Author’s construct)

However, despite the positive outcomes and opportunities associated with the LLA initiatives and practices of farmers and labourers in the community, their actions are limited by a lack of financial support. Indeed, adequate provisions and support have not been made for financial institutions to make credit facilities available to farmers and other members of the community. This is only compounded by the fact that the majority of the farmers live and thrive in rural areas where energy poverty is prevalent and income is very low.

3.2 Case II: Climate change adaptation strategies in the fisheries and aquaculture sector of Nigeria

Fisheries and aquaculture are two important sources of livelihoods in rural and peri-urban areas of Nigeria. However, climate change14 and other socioeconomic factors15 have led to the collapse of over 60% of the sector, leading to rising food insecurity, malnutrition and rates of unemployment.16 Recent studies have shown that Nigeria’s current fish production stands at 1.2 million metric tons per annum, while the demand has risen to 3.6 million metric tons per annum,17 which leaves a deficit of about 2.4 million metric tons per annum.18 The majority of the challenges facing fish farmers today are mostly attributed to the rising cost of feeds, land acquisition, flood inundation on fish farms, inadequate training, insecurity, lack of disease-resistant stocks, shortage of genetically improved seeds (fingerlings and juveniles), lack of adequate technology and insurance, low water quality, and lack of financial support, among others (see Box 2).19 Local fish farmers have devised several ways of overcoming some of these challenges, utilising locally sourced materials and employing traditional methods to improve the quality and quantity of fish produced, thereby contributing to environmental sustainability.

The results show that the farmers are motivated by the need to maintain their means of livelihoods and reduce the rising cost of fish farming. The practices and strategies employed by the fish farmers against climate change impacts include: drilling of deeper water boreholes for easy access to water (Fig. 5); training and apprenticeship programs which ensure that best practices are passed on; introduction of bitter leaf juice (Vernonia amygdalina) into the fish ponds to reduce fish mortality (bitter leaf juice contains antioxidants that helps in removing free radicals from the fish ponds); crossbreeding female Clarias gariepinus and male Heterobanchus longifilis to produce the hybrid Heteroclarias, which is very rugged and disease resistant (Fig. 6).

Despite these efforts, the farmers face major challenges and barriers stemming from lack of access to financial services (credit and insurance facilities and advisory) and technical support. This has made it very difficult for the farmers to acquire the necessary tools, skills, seed and feeds needed to sustain or expand their businesses.

Box 2: Narrative of a fish farmer on the impacts of climate change on the production of hatchlings (juveniles)

Under normal conditions, the eggs will hatch very well, but at the end of the day, because of heat, mortality increases. During the cold weather too, you could hardly have very good hatchlings (low success rate), because majority of the eggs will turn white, and production will be very low. How do you now alter that? You must adapt by increasing the heat in that place. If you don’t have an enclosed environment where you use for hatching, you’d have to do it yourself (improvise). Normally, you are supposed to have where you operate (within a climate-controlled room) to be able to achieve optimum results. We have been taking risks but now the climate change impacts are exacerbating the problem, plus the government that doesn’t give us any assistance because if you see the whole house in this Shagari estate here, everybody has borehole. There’s a problem, so we need an assistance (male participant, focus group discussion, Shagari estate, Lagos, Nigeria).

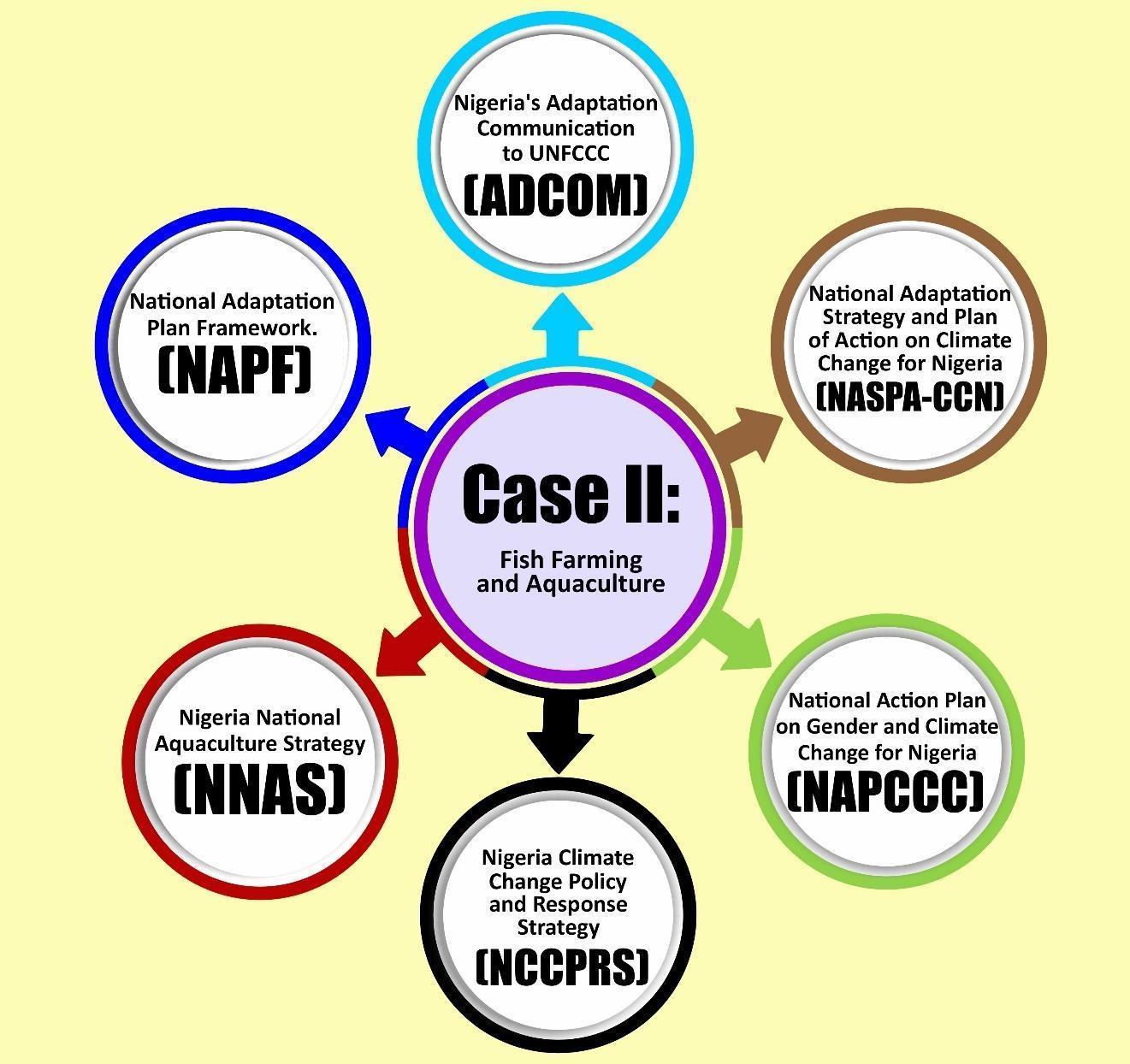

Alignment with NDCs and other national, regional and local policy priorities

The adaptation strategies and actions of the fish farmers are found within the three (3) NDC priority sectors including: agriculture, forestry and other land use (AFOLU); food security and health; and freshwater and coastal wetlands. The adaptation actions of the fish farmers are also fully aligned with several national policy frameworks, actions and strategies (Fig. 7). For example, the initiatives of the fish farmers to boost local production by integrating several nature-based solutions into their adaptation actions are in line with the NDC and the Nigeria National Fisheries Policy20, which aims to ‘achieve increased domestic fish production from all sources on a sustainable and renewable basis to the level of self-sufficiency and export in the medium to long term’. Furthermore, two important policy objectives of the Nigeria National Aquaculture Strategy (NNAS) are to: support accelerated fisheries and aquaculture production through private sector investment, and strengthen the socio-economic life in fishing communities by providing access to credit, inputs, equipment and facilities aligned with the adaptation actions of the fish farmers.

Figure 5: A typical catfish farming centre in Shagari estate, Alimosho LGA, Lagos State, Nigeria integrated with a borehole and water treatment plant. (Source: Author’s fieldwork)

Figure 6: Early stages of fish (fingerlings) development in an enclosed fish farm in Shagari estate. (Source: Author’s fieldwork)

Figure 7: Relationship between Case II and national policies and strategies. (Source: Author’s construct)

3.3 Case III: Adaptation practices of rural communities to land degradation in south-eastern Nigeria: lessons learned and opportunities for scale-up

Gully erosion is one of the most significant processes leading to land degradation in south-eastern Nigeria, oftentimes displacing several communities and resulting in forced migration and loss of livelihoods (Fig. 8). The frequency and magnitude of hazards and disasters caused by landslides and soil/gully erosion have been attributed to the high population density of the south-east region, coupled with erratic weather patterns that exacerbate these catastrophic events. Frontline communities in rural areas, whose sources of livelihoods are mostly subsistence agriculture and petty trading, are usually the hardest hit. However, the majority of these communities have learned to adapt to their changing environment by utilising traditional methods and local knowledge to minimise the risks of soil/gully erosion on their farms and farm roads. A typical example is Abatete town in Anambra State (south-eastern) Nigeria, where women, men and youths use various traditional methods to curb the effects of soil/gully erosion and landslides on market roads, farm roads and the vegetable/crop farms which serve as their major source of livelihood.

Figure 8: One of the gully erosion sites in Abatete, Idemili-North LGA, Anambra State, Nigeria. (Source: Author’s fieldwork)

Figure 9: Making of high ridges around vegetable beds to control flood inundation and sheet/rill erosion that may develop into gullies. (Source: Author’s fieldwork)

Therefore, understanding the adaptive capacities of these local communities against land degradation and the motivation behind their actions is important for improving climate resilience strategies. A series of discussions and interviews with key informants and residents of the community indicates that the major motivating factors behind their adaptation actions are to sustain their means of livelihoods; avert the fear of losing their homes, farms and access roads to soil/gully erosion; and yield associated co-benefits with the women farmers’ cooperative society (see Box 3). The major practices and strategies utilised by the community members to build resilience against the impacts of climate change include tree planting, use of sandbags and contour ploughing among others (Fig. 9).

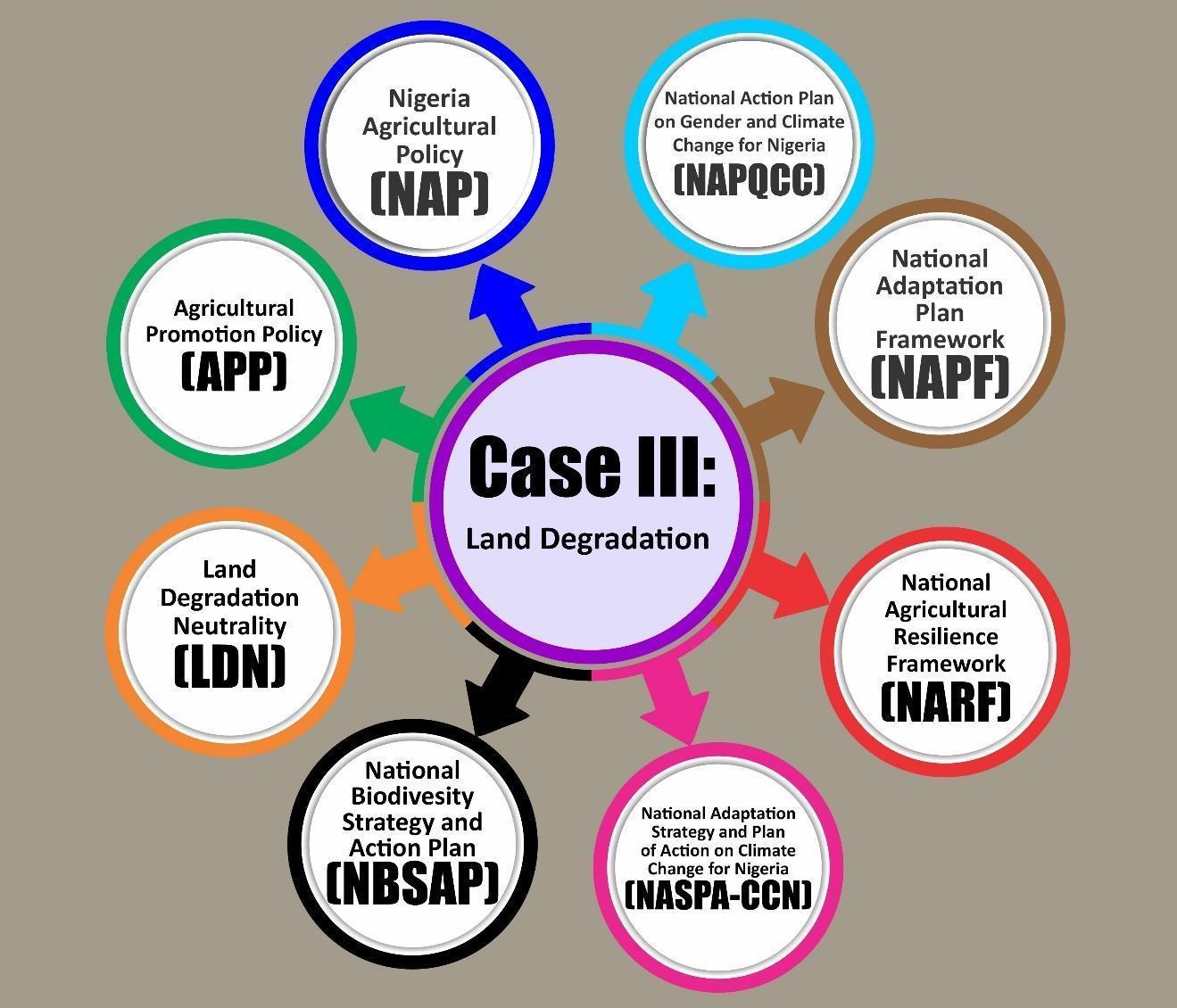

Alignment with NDCs and other national, regional and local policy priorities

The farmers’ actions have a direct connection to three (3) key priority sectors, which include agriculture, forest and biodiversity and are within the strategic plans of some national policies, such as the NASPA-CCN, NAPF, NAPGCC and the Land Degradation Neutrality (LDN) of Nigeria (Fig. 10). Others include the National Agricultural Policy (NAP), the Agricultural Promotion Policy (APP), the National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (NBSAP) and the National Agricultural Resilience Framework (NARF). However, these actions are only partially aligned with Nigeria’s NDC.

Box 3: Motivations behind the adaptation actions

Participant #5: We are taking these actions to help us to survive, because that's our only source of livelihood. We take these actions for economic reasons. The farm is where we get what we use to feed our children and train them in school. We also take these actions for easy access to our roads because people come to buy from us and we take these vegetables to other villages too. And if we don't take these actions, they cannot access our roads.

Figure 10: Relationship between Case III (land degradation) and national policies and strategies. (Source: Author’s construct)

Notwithstanding the lessons that can be learned from the adaptation actions of the local women, their actions are limited by lack of government support, limited access to financial services such as insurance policies and credit facilities, and poor government and policy support.

3.4 Analysis and discussion

As the above examples show, local communities in Nigeria are building resilience against climate change impacts and reducing natural disaster risks by integrating several LLA strategies and practices in their adaptation actions. The examples above reveal several behavioural, cultural and socioeconomic motivations driving LLA in the three case studies, including the need to sustain livelihoods, fight poverty and reduce food insecurity; the fear of losing their homes and businesses; the need for self-reliance; and the desire to ensure the sustainability of the environment. The majority of these adaptation actions are unique to each agro-ecological zone of Nigeria. For example, the integration of aquaculture and vegetable production (aquaponics), which is a sustainable method of water conservation and recycling, has helped local communities in the drought-prone regions of northern Nigeria to reduce food insecurity and sustain their livelihoods. Moreover, smallholder farmers in the southern region of Nigeria utilise a number of adaptation practices to mitigate seasonal flooding, flood inundations and land degradation. The farmers’ adaptation practices include intercropping, crop rotation, mixed farming, early planting and planting date adjustment, tree planting, and the construction of drainages.

However, local communities are experiencing many challenges in their efforts to protect their lives and livelihoods. The results obtained from the documentation of the three case studies on indigenous adaptation strategies and practices show that the major constraints to effective LLA implementation are lack of financial, human and infrastructural resources required to effectively plan and implement the LLA strategies. Other factors include lack of technical expertise and capacity to manage adaptation efforts, inadequate policies and regulations, weak governance and administration, and lack of awareness of the risks and consequences associated with climate change.

The case studies reveal several lessons that can be learned and integrated into Nigeria’s NAP Framework for effective actions against climate change impacts. The most important of these lessons is the need to integrate indigenous knowledge and traditional practices into LLA and climate action more broadly. Indigenous people’s knowledge and traditional practices contribute significantly to LLA and environmental sustainability by helping communities to diversify their livelihood systems as a way of coping with climate and environmental changes. Indigenous knowledge and traditional strategies and practices also help communities to integrate NbSs as an effective and sustainable response strategy against climate change impacts. These nature-based solutions include sustainable harvesting and use of resources, traditional ecological knowledge systems, and the research and monitoring of biodiversity and ecosystems. Another important lesson is the need to invest in stakeholder engagement inclusion in the leadership and management of adaptation actions. Part of the reason all the three LLA initiatives were successful is due to the fact that the projects were community-owned, context-specific and tailored to local needs. Therefore, investing in stakeholders and local actors ensures the inclusion of community members in the decision-making process, thereby ensuring ownership and creating buy-in.

While LLA is emerging as an important frontier for action in Nigeria, with the potential to improve livelihoods and resilience of communities, several gaps, barriers and challenges need to be addressed for it to be effective and sustainable. The four most important gaps the Nigerian government needs to close are capacity building, financial resources, technology development and access, and alignment of policy with regional adaptation needs, practices and strategies. These challenges limit Nigeria’s adaptive capacity and its ability to build resilience. The apparent exclusion of relevant stakeholders, such as youth, women, persons with disabilities, CSOs, indigenous people and local and state governments in the decision-making process is another major barrier to effective implementation of the APFs. Other limitations include the lack of an implementation timeline and target, lack of synergy and collaboration among stakeholders, the existence of numerous overlapping responsibilities, insufficient capacity/technical expertise to implement the NAP framework, and limited capacity to monitor, evaluate and document adaptation planning across the various spheres of governance.

4. Policy Recommendations for Effective LLA

This research has opened new opportunities for local and international stakeholders and policymakers to become active players in climate adaptation actions in all the agro-ecological zones of Nigeria. The results of the three case study analyses show that scaling up LLA initiatives in Nigeria has the potential to reduce climate change impacts in frontline communities and improve the livelihoods of rural communities by providing opportunity for capacity building, technology transfer, equitable funding and alignment of policies with regional adaptation needs. To achieve these much-desired goals and objectives, local policymakers and international actors must work together to develop clear adaptation action plans and implementation strategies that will improve the livelihoods and resilience of vulnerable communities. The specific recommendations for local policymakers and the international actors are as follows:

For local policymakers and other actors:

- Raise awareness about climate change, its impacts, adaptation measures and co-benefits beyond climate action benefits: Local policymakers and stakeholders should raise awareness about both climate change and its impacts, and adaptation measures so that frontline communities in all the agro-ecological zones of Nigeria can reduce vulnerability and build resilience against climate change impacts. The results of this research show that many communities have been engaging in adaptation actions for decades without an in-depth understanding of climate change. Therefore, local actors and policymakers need to mainstream climate change and its potential impacts across all spheres of governance, with a special emphasis on frontline communities who are the hardest hit by climate-related disasters. Furthermore, local policymakers and stakeholders should encourage education and capacity building to enhance adaptation efforts, especially in rural communities.

- Build partnerships with local research institutions, private organisations and tertiary institutions for effective climate change adaptation actions: Local policymakers and stakeholders need to work closely with local research institutions, private organisations and tertiary institutions to develop innovative solutions, ideas and products that will improve the adaptive capacities of frontline communities and reduce vulnerability to the impacts of climate change. For example, access to energy from biomass/biogas systems can be improved by partnering with the Renewable Energy Technology Training Institute (RETTI), the National Centre for Energy Research & Development (NCERD), and the Forestry Research Institute of Nigeria, to scale up the production of energy from biogas and develop cleaner cooking fuels and stoves while conserving scarce forest resources. Similarly, innovative fish feeds and climate-resilient fisheries and other marine resources should be developed by local stakeholders in collaboration with the National Institute for Freshwater Fisheries Research (NIFFR) and the Nigerian Institute for Oceanography and Marine Research (NIOMR). Finally, to curb land degradation, rural farmers need to partner with local, state and national agricultural research institutes to build resilience against climate-induced land degradation by planting erosion-resistant crops, practising crop diversification and investing in other traditional methods that will improve soil health and decrease land degradation.

- Promotion of EbA: Local actors and stakeholders need to understand the significance of protecting and restoring Nigeria’s natural ecosystems including the Freshwater Swamp Forests, Mangrove Swamp and Coastal Vegetation, Lowland Rain Forests, and Derived/Guinea/Sudan/Sahel Savanna, which can provide natural buffers against climate change impacts such as flooding, erosion, land degradation, desertification and bush fires. Nigeria’s agro-ecological zones have different ecosystems that require the utilisation of NbSs and other ecosystem services to improve the environmental sustainability and livelihoods of rural communities as observed in the three case studies presented in this research. For example, the deep dive results showed that the local communities are taking climate adaptation actions by integrating NbSs and local methods to reduce vulnerability and build resilience. In case study I, the community is adapting to the impacts of climate change by converting organic waste generated from crop, livestock and poultry farming into a clean energy source (biogas), thus conserving the nearly depleted forest resources and restoring biodiversity. In case study II, the fish farmers have introduced locally sourced feeds as one of their LLA initiatives. Meanwhile, in case study III, the local farmers plant erosion-resistant trees at gully erosion hotspots to reduce gully erosion disasters and restore the environment. These EbA strategies need to be well documented by state and regional government agencies so that the lessons learned from them can be shared with other communities and regions within Nigeria and beyond.

- Encourage and support the adoption of climate-smart agricultural practices, such as crop diversification, fish hybridisation and the use of drought-resistant and heat-tolerant crop varieties: Local actors should encourage the adoption of climate-smart agricultural practices, such as crop diversification, fish hybridisation and the use of drought-resistant and heat-tolerant crop varieties. This is by far the most important recommendation since about 90% of Nigeria’s food is produced by smallholder farmers who practise subsistence agriculture. The agricultural sector of Nigeria is mostly rainfed and only 1% of the country’s cropland is irrigated despite the fact that the sector accounts for about 23.78% of its GDP. Therefore, local actors should work with relevant organisations and government agencies to invest in climate-smart agricultural practices with a view to promoting livelihood diversification and the socioeconomic wellbeing of rural communities.

For the international community:

- Allocate financial resources to support comprehensive climate research and data collection, especially with reference to local and indigenous knowledge, practices and strategies: The international community should seek partnership with the Nigerian government and local institutions to allocate resources needed to support comprehensive climate research and data collection. This information will provide a solid foundation for evidence-based decision-making, risk assessments and adaptation planning. This kind of data is also important to ensure that climate change adaptation plans are formulated to reflect the local knowledge, traditional values and cultures of various communities and ethnic groups within Nigeria, and will help to give them agency overall adaptation actions.

- Provide concrete and sustained finance in the form of grants to close technology gaps: International actors should assist Nigeria to close technology gaps in the areas of renewable energy development, fisheries and aquaculture production, forest conservation, and environmental protection, by investing in capacity building and making funds available for research in these areas. Also, international financial institutions need to liaise more with local stakeholders to ensure that frontline communities have access to climate adaptation finance. This is urgently needed to develop weather-tolerant seedlings, integrated solar systems for irrigation systems in parched land, early-warning systems to monitor erratic weather patterns, and to improve fisheries and aquaculture productivity.

- Provide and facilitate the availability and affordability of climate insurance to help vulnerable communities recover from climate-related disasters: Nigeria has a significant number of pastoralists, smallholder farmers and small and medium-scale entrepreneurs. To help these vulnerable communities recover from climate-related disasters, the international community should work closely with local, state and federal government agencies and relevant funding agencies to facilitate the availability and affordability of climate insurance. So far, adaptation efforts have often been insufficient, especially in the event of loss and damages.

5. Conclusion

Nigeria is facing a deepening climate crisis which has aggravated its fragility risks. The accelerating frequency of extreme weather events in the country has led to incessant flooding, storm surges, droughts, desertification, sea level rise, soil and gully erosion, and loss of biodiversity. In recent years, the Nigerian government has developed several adaptation policy frameworks (APFs) in their bid to build resilience against these impacts of climate change and improve the lives and livelihoods of frontline communities. However, the majority of these APFs lack proper implementation plans and are only partially aligned with the key economic policies. Furthermore, the roles of local communities in the NAP Framework have not been properly defined.

Despite limited external support or awareness of national and international policies and strategies, preliminary results show that local communities, informed and supported by indigenous and traditional knowledge systems, generally employ innovative and multilayer strategies, practices and tools to support their lives and livelihoods. Moreover, the analysis above shows that these strategies, practices and tools are consistent with national and international climate action policies, strategies and goals.

However, to align local actions with national and international climate actions, policies, strategies, and goals, the Nigerian government needs to close three important gaps: capacity building, financial support and technology development and access. Other barriers include: the apparent exclusion of relevant stakeholders such as women, persons with disabilities, CSOs, indigenous people, local and state governments in the decision-making process; a lack of implementation timelines and targets; a lack of synergy and collaboration among stakeholders; the existence of numerous overlapping responsibilities; insufficient capacity to implement the NAP framework; and a limited capacity to monitor, evaluate and document adaptation planning across the various spheres of governance. These challenges limit Nigeria’s adaptive capacity and its ability to build resilience.

The development and implementation of an integrated policy framework, one that includes local communities’ LLA strategies, will therefore be vital for building resilience and reducing climate-induced hazards and disasters. In particular, the Nigerian government has the opportunity to involve local communities, indigenous people, women, CSOs and youth, ensuring that they lead the way by contributing to every decision-making process that leads to climate adaptation actions. Finally, the FGN has the opportunity to work closely with local communities involved in locally led adaptation to identify viable projects that can be scaled up and integrated into the NAP framework.

Endnotes

1 World Bank. (2021). World Bank Country Data 2021. Retrieved from: Nigeria | Data (worldbank.org).

2 Kamer, L. (2022). African countries with the highest Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2021 (in billion US dollars). Accessed 15th March, 2023; Africa: GDP by country 2021 | Statista

3 Nasir, M. (2022). Deep Structural Reforms Guided by Evidence Are Urgently Needed to Lift Millions of Nigerians Out of Poverty, says New World Bank Report | Press release. Accessed 30th March, 2023; Nigeria Poverty Assessment (worldbank.org).

4 Adelekan, I.O., Simpson, N.P., Totin, E., Trisos, C.H. (2022). IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (AR6): Climate Change 2022 - Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability: Regional Factsheet Africa. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Switzerland. Retrieved fromhttps://policycommons.net/artifacts/2264240/ipcc_ar6_wgii_factsheet_africa/3023294/on 11 Apr 2023. CID: 20.500.12592/7qn5fk.

5 Verisk Maplecroft. (2016). Climate Change Vulnerability Index. Verisk Analytics. https://www.maplecroft.com/risk-indices/climate-change-vulnerability-index/

6 University of Notre Dame (2021). Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative | Rankings. Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative https://gain.nd.edu/our-work/countryindex/rankings/

7 Okunola, O. (2021). What do we know about disaster risk practices in Nigeria? United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Management (originally published by The Daily Sun). Retrieved from https://www.preventionweb.net/news/what-do-we-know-about-disaster-risk-reduction-practices-nigeria on 11 November 2022

8 UNDP. (2021). Nigeria | Climate Promise. United Nations Development Programme. (last updated January 2023). Retrieved from: https://climatepromise.undp.org/what-we-do/where-we-work/nigeria

9World Bank. (2021). Climate Change Could Further Impact Africa’s Recovery, Pushing 86 Million Africans to Migrate Within Their Own Countries by 2050 | Press Release. The World Bank. Retrieved from: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2021/10/27/climate-change-could-further-impact-africa-s-recovery-pushing-86-million-africans-to-migrate-within-their-own-countries

10 WHO. (2021). World Malaria Report 2021. Global report. World Health Organization. Retrieved from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240040496

11 Soanes, M., Bahadur, A., Shakya, C., Smith, B., Patel, S., del Rio, C. R., ... & Mann, T. (2021). Principles for locally led adaptation.International Institute for Environment and Development London, UK.

12 Coger T, Dinshaw A, Tye S, Kratzer B, Aung MT, Cunningham E, Ramkissoon C, Gupta S, Bodrud-Doza M, Karamallis A, Mbewe S. (2022). Locally Led Adaptation: From Principles to Practice. World Resources Institute. www.wri. org/research/locally-led-adaptation-principles-practice.

13 NwaNri N, Owoeye F (2022) In Nigeria’s disappearing forests, loggers outnumber trees – a photo essay.Reuters. Retrieved from: https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/nigeria-environment-trees/

4 Olutumise, A. I. (2023). Impact of relaxing flood policy interventions on fish production: lessons from earthen pond-based farmers in Southwest Nigeria. Aquaculture International, 1-24.

15 Falola, A., Mukaila, R., & Emmanuel, J. O. (2022). Economic analysis of small-scale fish farms and fund security in North-Central Nigeria.Aquaculture International,30(6), 2937-2952.

16 Yakubu, S. O., Falconer, L., & Telfer, T. C. (2022). Scenario analysis and land use change modelling reveal opportunities and challenges for sustainable expansion of aquaculture in Nigeria.Aquaculture Reports,23, 101071.

17 The Nation. (2022). Nigeria needs 3.6 metric tonnes of fish annually. The Nation Newspaper. Retrieved from: 'Nigeria needs 3.6 million metric tonnes of fish annually' | The Nation Newspaper (thenationonlineng.net)

18 Falaju, J. (2022). FG raises concern over 2.4 million tonnes domestic fish deficit. The Guardian Newspaper. Retrieved from: FG raises concern over 2.4 million tonnes domestic fish deficit — Business — The Guardian Nigeria News – Nigeria and World News

19 Onyenekwe, C. S., Sarpong, D. B., Egyir, I. S., Opata, P. I., & Oyinbo, O. (2022). A comparative study of farming and fishing households’ livelihood vulnerability in the Niger Delta, Nigeria.Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 1-25.

20 Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development. (2008). Nigeria - National Aquaculture Strategy.Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved from: https://www.fao.org/faolex/results/details/en/c/LEX-FAOC189027/

About the Author

Dr. Chukwueloka Udechukwu Okeke

Dr. Chukwueloka Udechukwu Okeke, a Senior Lecturer at Anchor University, Lagos State, Nigeria, specializes in climate change adaptation, environmental sustainability, geological hazards, and disaster risk reduction. With a background in Geology and extensive international experience, he contributes to research and is affiliated with professional organizations and currently serves as an editorial board member of Geoenvironmental Disasters – a SpringerOpen journal.