Summary

- The severe health impacts of climate change, such as heat-related illnesses, infectious diseases, and mental health issues are diverse and vary across Senegal’s ecological zones.

- These impacts pose a substantial threat to the attainment of Sustainable Development Goals, particularly SDG 3, which focuses on health and wellbeing.

- Adaptation and mitigation efforts are both vital in protecting health and wellbeing and building long-term resilience in Senegal.

- The scope and diversity of climate change-induced health and wellbeing-related challenges demand nothing less than a coordinated and intersectional response to guarantee effective and sustained results.

Introduction and Background

Climate change in Sahelian countries like Senegal leads to disasters such as droughts, floods, and heatwaves which endanger food security, public health, water resources, the environment, biodiversity, and socioeconomic sectors.3,4,5 The combined effects of these factors pose a substantial threat to the attainment of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs),6,7 particularly SDG 3, which focuses on health and wellbeing. This highlights that climate change is not solely an environmental issue, but also a health crisis that demands immediate and coordinated action at all levels of society. While the government of Senegal and its partners are implementing policies and strategies to address climate-related health challenges, including resilient infrastructure, sustainable agriculture, and community awareness, it is crucial to develop an understanding of the diverse, context-specific climatic phenomena in different regions of Senegal to provide targeted, effective, and sustainable solutions at a local level. This analysis examines the challenges and opportunities to support at-risk populations in Senegal.

Senegal´s Varied Climate Change Impacts

Coastal regions of Senegal, including Dakar, face rising sea levels that produce erosion threats to coastal infrastructure and ecosystems, as well as the increased risk of storms and floods.8 Sahelian regions experience more frequent and severe droughts, impacting agriculture and food security9 because desertification and land degradation adversely affect farming and livestock communities here.10,11 The Sudan-Sahel region also experiences climatic variations that affect agriculture.12 Regions like Casamance face flooding risks due to heavy rainfall.

Northern and northeastern regions are subject to more arid conditions and face increasing desertification which threatens local livelihoods. While a common characteristic of Senegal's climate is related to the variability of temperature and rainfall, the impacts directly influence a diverse range of sectors that support health and wellbeing, such as food and water security, biodiversity, and the economy.

Climate Change and Health Impacts in Senegal

According to recently published studies on the burden of diseases related to climate and environmental changes in Senegal,13,14 the impact of severe heat waves leads to heat-related illnesses and exacerbates chronic conditions.15 Altered precipitation patterns cause prolonged droughts, water scarcity, and waterborne diseases. Flooding damages healthcare infrastructure, contaminates water sources, and promotes diseases like cholera.16 Temperature and precipitation changes impact disease vectors like mosquitoes, facilitating the spread of dengue and malaria.17,18

Climate change also disrupts agriculture and threatens food security,19 which can result in malnutrition and other related health issues.20 Moreover, climate-induced population movements, resource depletion, and environmental degradation worsen health issues and vulnerability to diseases, risking resource-related conflicts.

Due to these growing risks and impacts, comprehensive responses to boost adaptive responses and resilience in healthcare policy, water management, agriculture, and environmental preservation are essential. Such actions are already evident in Senegal, but more needs to be done to protect affected communities and mitigate further damages and risks. The following section discusses a local community´s innovative strategies, supported by the government and other external actors, to adapt and build resilience in the face of climate change´s health impacts.

Local Strategies for Climate-Resilient Health: Widou Thiéngoly Island 21

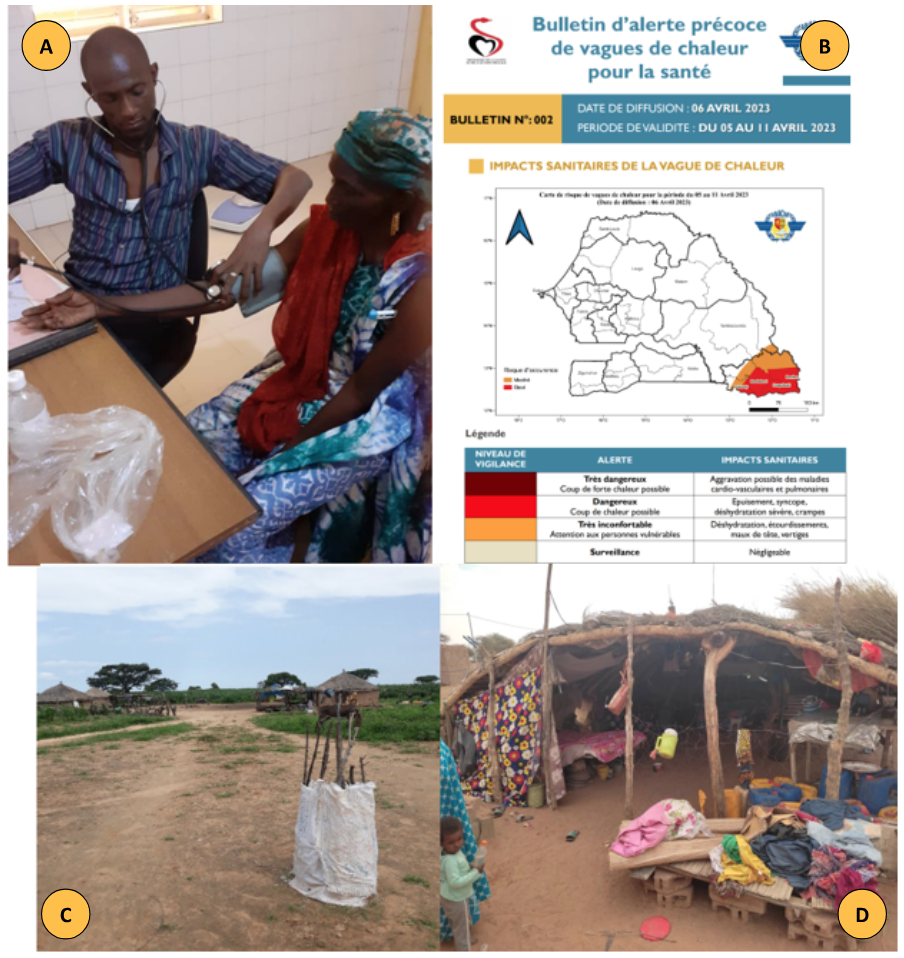

Widou Thiéngoly is in the heart of a semi-arid tropical climate (SATC) with a long dry season from October to June characterized by very high temperatures reaching 46-48°C. The project spotlighted here is designed to address the health impacts of heatwaves. Initiated by local stakeholders, the project is implemented and managed in close collaboration with the Ministry of Health and Social Action (MSAS), the National Agency for Civil Aviation and Meteorology (ANACIM), the Centre for Ecological Monitoring (CSE), the Directorate of Civil Protection (DPC), the Senegalese National Red Cross Society (CRNS), the Great Green Wall Agency (AGMV), the Health Development Committee (CDS), and the Association of Borehole Users (ASUFOR). Key strategies and actions include early warning systems, public reforestation, concessions to counter heat and air pollution, bioclimatic architecture for heat-adapted habitats, and free medical consultations to mitigate heatwave health risks (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Picture board of local community adaptation practices to health risk resilience in Widou Thiéngoly

Climate adaptation and health resilience practices driven by community awareness of heat wave risks reduce health costs and climate-sensitive diseases. Although challenges like limited resources and data gaps exist, these projects can serve as examples for broader actions in Senegal. The example also demonstrates that with more sustained support, access to climate information, capacity-building, and knowledge sharing about climate´s health impacts, progress can be made.

Conclusion and Way Forward to COP28

This analysis has shown that there is an overwhelming experience of climate change-induced impacts on the health and wellbeing amongst Senegalese populations. While efforts to adapt and build resilience are underway, the scope and diversity of climate change-induced health and wellbeing challenges faced by Senegal demand a coordinated and intersectional response. This must integrate health and climate change policies and invest in healthcare infrastructures that guarantee effective and sustained results. Prioritizing at-risk populations is crucial in the context of limited climate finance support and shrinking fiscal space for African governments like Senegal.

COP28 is the first COP to dedicate a day to address the intersection of health and climate change.23 This should address both short and long-term solutions such as: health loss and damages, financial support for climate-resilient infrastructure and early warning systems, transition to clean energy, strengthening healthcare systems for climate-related health emergencies, and the promotion of agriculture and food security. The stakes are high and previous COPs indicate that negotiations could dominate the time available on the day dedicated to health. This would be a mistake. COP28 must yield actionable commitments to protect vulnerable populations in countries like Senegal before it is too late.

Endnotes

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). (2017). Climate change and health. Retrieved from https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/sustainable-development-goals/goal-3-good-health-and-well-being/targets/climate-change-and-health?search=Goal+3.

- Guégan, J. F., Suzán, G., Kati-Coulibaly, S., Bonpamgue, D. N., & Moatti, J. P. (2018). Sustainable Development Goal #3, "health and well-being," and the need for more integrative thinking. Veterinaria México OA, 5(2), 0-

- Haines, A., Kovats, R. S., Campbell-Lendrum, D., & Corvalan, C. (2006). Climate change and human health: Impacts, vulnerability, and mitigation. The Lancet, 367(9528), 2101-2109.

- Coulibaly, N., Coulibaly, T. J. H., Mpakama, Z., & Savané, I. (2018). The impact of climate change on water resource availability in a trans-boundary basin in West Africa: The case of Sassandra. Hydrology, 5(1), 12.

- Diouf I, Adeola AM, Abiodun GJ, Lennard C, Shirinde JM, Yaka P, Ndione JA, Gbobaniyi EO. (2022). Impact of future climate change on malaria in West Africa. Theoretical and Applied Climatology, 1-3.

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). (2017). Climate change and health. Retrieved from https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/sustainable-development-goals/goal-3-good-health-and-well-being/targets/climate-change-and-health?search=Goal+3.

- Guégan, J. F., Suzán, G., Kati-Coulibaly, S., Bonpamgue, D. N., & Moatti, J. P. (2018). Sustainable Development Goal #3, "health and well-being," and the need for more integrative thinking. Veterinaria México OA, 5(2), 0-

- Dennis, K.C., Niang-Diop, I. and Nicholls, R.J. (1995) Sea-level rise and Senegal: Potential impacts and consequences. Journal of Coastal Research, Special Issue. 14: 243-261.

- Nébié, E. K. I., Ba, D., & Giannini, A. (2021). Food security and climate shocks in Senegal: Who and where are the most vulnerable households? Global Food Security, 29, 100513.

- Gonzalez, P., C. J. Tucker and H. Sy, 2012. Tree density and species decline in the African Sahel attributable to climate. J. Arid Env., 78, 55-64.

- Asante Gyamerah, S., & Ikpe, D. (2021). A review of effects of climate change on Agriculture in Africa. arXiv e-prints, arXiv-2108.

- Ahmed, A., Suleiman, M., Abubakar, M. J., & Saleh, A. (2021). Impacts of climate change on agriculture in Senegal: A systematic review. Journal of Sustainability, Environment and Peace, 4(1), 30-38.

- Sy, I., Cisse, B., Ndao, B., Toure, M., Diouf, A. A., Sarr, M. A., … & Ndione, J. A. (2022). Heat waves and health risks in the northern part of Senegal: analyzing the distribution of temperature-related diseases and associated risk factors. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 29(55), 83365-83377.

- Ngom, El H. M., Faye, D. N., Talla, C., Ndiaye, El H., Ndione, J-A., Faye, O., Ba, Y., Diallo, M., & Dia, I. (2014). Anopheles arabiensis seasonal densities and infection rates in relation to landscape classes and climatic parameters in a Sahelian area of Senegal. BMC Infectious Diseases, 14, 711.

- Faye, M., Deme, A., Diongue, A. K., & Diouf, I. (2021). Impact of different heat wave definitions on daily mortality in Bandafassi, Senegal. PLoS ONE, 16(4), e0249199.

- FALL, S. (2020). Assessing the impacts of Climate Change in Senegal: A Case Study of Casamance Region (Master's thesis, PAUWES).

- Diouf I, Ndione JA, Gaye, A. T. (2022). Malaria in Senegal: Recent and Future Changes Based on Bias-Corrected CMIP6 Simulations. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 7(11):345.

- Diouf, I., Sy, I., Diouf, D., Ndione, J.-A., & Gaye, A. T. (2023). An overview of Climate Change Impacts on the Health Sector for the Research Program of the National Adaptation Plan Support Project in Senegal. SOAPHYS (Société Ouest Africaine de Physique), Journal, accepted.

- Paeth, H., Capo-Chichi, A., & Endlicher, W. (2008). Climate change and food security in tropical West Africa—a dynamic-statistical modelling approach. erdkunde, 101-115.

- FAO. (2015). Climate change and food security: risks and responses. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2015.

- This study was produced by APRI - Africa Policy Research Institute, a Berlin-based, independent, non-partisan African think tank researching key policy issues affecting the African continent — in close collaboration with ENDA Energy, an international non-governmental organization with headquarters in Dakar, Senegal. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of APRI or ENDA concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. For more information on the timelines and methodology please see the ….. “report” available here

- Photos taken by APRI researchers. African Policy Research Institute (2023)

- WHO. (2023). Leaders spotlight the critical intersection between and climate ahead of COP-28's first-ever Health Day. World Health Organization. Available at: https://www.who.int/news/item/18-09-2023-leaders-spotlight-the-critical-intersection-between-health-and-climate-ahead-of-cop-s-first-ever-health-day

About the Authors

Dr. Ibrahima Diouf

Dr. Ibrahima Diouf completed his collaborative Ph.D. thesis between the University Cheikh Anta Diop of Dakar (UCAD) in Senegal and the Universidad Complutense of Madrid (UCM) in Spain in 2016, focusing on atmospheric and oceanic physics with applications in climate and health studies. His post-doctoral work centers on climate and health issues, seasonal predictions, climate change impacts on vector-borne diseases, and adaptation strategies in West Africa.

Dr. Ibrahima Sy

Dr. Ibrahima Sy is a Senior Climate Change Fellow at APRI. He is currently a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Geography at the University Cheikh Anta Diop (UCAD), Dakar, Senegal. He is an Associate Researcher with the Centre for Ecological Monitoring (CSE) in Dakar.

Dr. Grace Mbungu

Dr. Grace Mbungu is a Senior Fellow and Head of the Climate Change Program at the Africa Policy Research Institute (APRI), supporting policymakers with timely and evidence-based policy options to enable the creation of long-term, sustainable, and inclusive wellbeing and livelihood opportunities.