Africa’s geostrategic alignments in response to the Ukraine war

This paper sheds light on several options African countries could explore in their attempt to pursue and advance their political, economic and social interests amid an evolving geopolitical landscape.

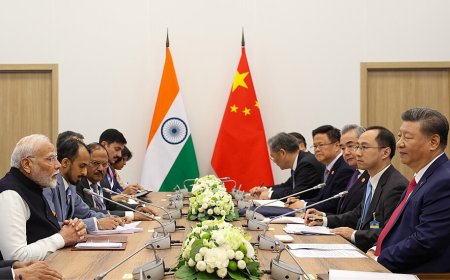

Photo by Basil D Soufi via Wikimedia, CC BY-SA 3.0

This article is part of a series on the effects of the war in Ukraine on African countries. The series is edited by Chris O. Ogunmodede.

Summary

- Broadly speaking, African countries have condemned Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, as individual states as well as collectively through the African Union.

- African countries can and must do more to pursue and advance their political, economic and social interests amid an evolving geopolitical landscape. There are several options African countries could explore in their attempt to secure those interests.

- First, African countries could take a pragmatic leadership role in negotiations for peace between Russia and Ukraine, by publicly offering to facilitate, host or observe negotiations as individual countries or representatives of regional blocs.

- Second, African nations must take advantage of the resource gaps left by Western sanctions against Russia by brokering equitable and sustainable trade agreements with affected countries.

- Thirdly, African countries must diversify their sources of commodities, including oil and wheat, in order to provide much-needed stability against fluctuating commodity prices and industry shocks.

- Finally, while much attention has been paid to the impact of Russia’s actions on trans-Atlantic and regional partnerships, African countries must use this historical happening as an opportunity to introspect about the status of continental unity, pan-African solidarity and regional relations.

- The implementation and success of these proposals relies on the willingness of African leaders to make bold decisions while paying enough attention to domestic as well as international considerations. African countries should not be positioned as passive bystanders to events happening in an increasingly changing world.

Russian President Vladimir Putin authorised a “special military operation” against Ukraine on Feb. 24, after which Russian troops invaded Ukraine. Moscow’s incursion has now come to be regarded as perhaps the most significant challenge to the international rules-based order in the post-Cold War era, with the war in Ukraine raising important questions about the sanctity of territorial integrity and sovereignty, the effectiveness of economic sanctions, security alliances and nuclear disarmament.

Almost immediately after Russian troops invaded Ukraine, Western nations and international organisations moved swiftly to condemn Moscow through diplomatic statements denouncing Russia’s aggression, imposing far-reaching sanctions, and providing large-scale military and humanitarian assistance to Ukraine. Months into the fighting, the broader ramifications of the war in Ukraine are coming into clearer focus. These implications include an increase in fuel and grain prices in many parts of the world, trade disruptions and worsening security relations between global powers, all of which are happening in the foreground of a fragile recovery from the coronavirus. These outcomes have coincided with a deeper clarification of global politics amid the war in Ukraine, with many observers taxonomizing the international response to the conflict into two broad categories: those supporting Western positions against Russia, and others that do not. But for many countries particularly in Africa, the larger question beyond their individual positions on the war is whether they can manage the global ramifications of the evolving geopolitical landscape regardless of what positions they adopt, and how.

A good starting point would examine how different African countries responded to Russia’s invasion, with a view to considering how they could safeguard and pursue their national interests amid the conflict, and beyond. This careful assessment of the distinct positions that African countries have cautiously and deliberately adopted amid fluid developments also allows for the opportunity to assess the long-term risks as well as opportunities that lie ahead for African countries in the geopolitical landscape.

Broadly speaking, African countries have condemned Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, as individual states as well as collectively through the African Union. An entry point for African countries that directly condemned Russia’s actions is a speech by Martin Kimani, Kenya’s ambassador to the United Nations, that drew parallels between Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and Africa’s experience of European colonisation. In drawing that comparison, Kimani expressed African solidarity with Ukraine by articulating African countries’ commitment to national sovereignty, territorial integrity, the rules-based international order and resolving disputes through non-violent means. This norm-based solidarity could be detected among the 28 of the African Union’s 54 member states—including Botswana, Cabo Verde, Ghana, Malawi, Mauritius, Niger, Nigeria, Kenya, Seychelles, Sierra Leone and Zambia—that voted in support of a March U.N. General Assembly resolution condemning Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and demanding a withdrawal of its troops.

But while the position taken by those countries seemingly put them on the same side as the United States and its European allies, many African observers were also quick to point to double standards on the part of Ukraine and Western countries during the ongoing crisis. For instance, Kenya expressed “deep concern” over the discriminatory treatment Africans faced in Ukraine— as well as in neighbouring countries— as they attempted to leave Ukraine amid the fighting. Many others decried double standards seen on display in the disparity in international media coverage of the war in Ukraine as compared with crises in Africa and elsewhere, to say nothing of the outpouring of financial and other forms of assistance Ukraine received, of which emergencies in Africa rarely receive.

The statement released by the AU on the same day Russia launched the invasion of Ukraine echoed sentiments expressed by Kenya and other African countries. In doing so, the AU positioned the continent as willing to support peacemaking efforts within the framework of the existing Western-led international order. Similarly, the Economic Community of West African States, or ECOWAS, adopted a position of non-alignment by referring to Cold War legacies of global political polarisation.

For its part, South Africa attempted to take what President Cyril Ramaphosa described as a “balanced” approach, by refusing to explicitly name Russia or directly condemning its invasion. Pretoria presented a resolution at the U.N. that outlined steps Russia and Ukraine needed to take in order to come to a ceasefire and long-term peaceful settlement through mediation—without acknowledging Russia’s role as an aggressor in the crisis. But while South Africa’s UN proposal did little to assuage Western critics and their concerns, Pretoria’s positioning as a willing mediator helped shore up its credibility as a norm entrepreneur, as well as its relationship with Moscow, which includes bilateral partnerships as well as multilateral relations within BRICS, which both countries are members of.

For the 26 African countries that either voted against the resolution, abstained from voting or did not vote at all, condemnation of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was arguably not an option for several reasons. The most frequently alluded to was their desire to maintain good relations with Moscow due to existing bilateral ties, mutual scepticism of the Western-led order and military cooperation that underscores Russia’s notable soft power influence on the continent.

But while it is true that African countries came under pressure from the U.S. and its European allies to condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine—or at least abstain from overtly siding with Russia—and efforts by African countries to stave off diplomatic and moral campaigns to essentially take sides make sense, African countries can and must do more to be proactive about securing interests amid an evolving geopolitical landscape.

There are several options African countries could explore in their attempt to do so. First, African countries could take a pragmatic leadership role in negotiations for peace between Russia and Ukraine, much like the AU has offered to do. Through this, they could raise their profile on the international stage as capable and trustworthy mediators, while being seen to uphold global peacebuilding and cooperation norms. Their proactive participation in international peace and security initiatives could enhance their existing bilateral as well as multilateral relationships with multiple partners, and present African countries with an opportunity to articulate their own vision of what a truly international rules-based order should look like and how it could be realised.

Second, African nations must take advantage of resource gaps created by Western sanctions against Russia. Brokering new, equitable agreements will be crucial in determining the extent to which African countries are able to leverage the geopolitical landscape in Europe and elsewhere to their advantage. For instance, energy and commodity-rich countries like Angola, Mozambique and Libya should look to fill shortfalls in oil, maize, mineral and gas supplies to Europe as the European Union moves to reduce its dependency on energy imports from Russia. Pursuing these arrangements through sustainable trade relations will go a long way in boosting national and regional economies, create African jobs, enhance socio-political stability and increase investor confidence. By taking an intentional approach to securing their interests amid lots of global uncertainties, African countries can avoid a new ‘scramble for Africa’ where foreign powers seek to exploit African resources through long-term unequal relations as has happened in the past.

Thirdly, African countries must diversify their sources of commodity imports like oil and wheat. Since the launch of Russia’s invasion, African households have been hit hard by rising oil, gas and wheat prices, not least because they import large volumes of these commodities from Russia and Ukraine. The knock-on effects of rising commodity costs on agriculture and transport sectors are considerable, which in turn adversely affects the continent’s economic recovery from the coronavirus pandemic. To cite one example, Zambia agreed to cut national fuel subsidies in order to abide by debt negotiations with the International Monetary Fund. But the rising cost of fuel and other commodities makes such reforms politically unpopular. A diversification of suppliers may provide much-needed stability against fluctuating commodity prices and industry shocks.

Finally, while much attention has been paid to the impact of Russia’s actions on trans-Atlantic and regional partnerships, the invasion of Ukraine presents an opportunity for Africa to do some introspection about the status of continental unity, pan-African solidarity and regional relations. The recent spate of coups in West Africa has exposed the inability of regional and continental organisations to respond coherently to norm violations by their member states. AU, ECOWAS and SADC, positions on unconstitutional changes of government have been regularly undermined by some of their own member states. Disunity within these organisations is hardly new but its root causes should nonetheless be addressed if African countries are to form a consensus and speak with one voice on key international issues. The ability to build a common position on major issues of peace, security and governance also bodes well in the long term for continental cooperation as well as for the credibility of Africa’s regional institutions.

The implementation and success of these proposals undoubtedly relies on the ability of African leaders to make bold decisions while paying enough attention to domestic and international considerations. It is no longer sufficient for African countries to be merely positioned as passive bystanders to events happening in an increasingly changing world. These recommendations articulate a way for African countries to navigate an evolving geopolitical landscape that will have major ramifications for their affairs.

About the Author

Aaliyah Vayez

Aaliyah Vayez is a South African political and security risk analyst. Her main research interests include European politics, African foreign policy and regionalism. She holds a Masters degree in International Relations at the London School of Economics and Political Sciences, a Bachelor's degree of Social Science and an Honours degree in International Relations from the University of Cape Town.