Introduction

The challenge of solving Africa’s infrastructure deficit has been an ever-present fixture in global development discourse. The African Development Bank (AfDB) estimates that the continent requires USD 130 - USD 170 billion per year in infrastructure financing. This translates to an annual deficit of USD 68 - 108 billion (African Development Bank, 2023). The costs of using infrastructure services in Africa are multiple times higher than in other regions. Energy costs for manufacturing enterprises are up to four times higher, road freight tariffs are two times higher than in markets such as the United States and travel times along critical export corridors are up to three times higher than those in Asia. Telecommunications costs are also high, with mobile and internet services costing about four times as much as in South Asia (African Development Bank,2023). Meanwhile, access to electricity, improved sanitation and water in Africa are among the lowest in the world (Afrobarometer, 2024). Beyond challenges relating to the cost of and access to infrastructure services, the quality of these services is also low on average. Together, these have contributed to the estimation that poor infrastructure has resulted in a 40% loss in productivity in African countries and up to a 2-percentage point reduction in annual national economic growth (African Union, 2023).

The high annual infrastructure deficit exists in the context of the poor fiscal situation of many African governments. In 2021, the average tax-to-GDP ratio for 33 African countries stood at 15.6% (Revenue Statistics in Africa, 2023). This is low in comparison to the averages for other developing regions, such as Asia-Pacific (19.8%) and Latin America and the Caribbean (21.7%). According to the World Bank (2023), between 2021 and 2022, the fiscal deficit in the sub-Saharan African region widened from 4.8% of GDP to 5.2% of GDP. Some African countries are also facing debt defaults or distress. The World Bank (2023) again estimates that the median public debt-to-GDP ratio in sub-Saharan Africa grew from 32% in 2010 to 57% in 2022 and that 22 countries in the region are facing or at a high risk of debt distress. Bilateral infrastructure lending from newer partners like China has also declined. It was estimated that in 2022, Chinese loan commitments to African countries fell to their lowest level since 2004 (Moses et al., 2023).

The launch of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) agreement in January 2021 has increased the urgency for infrastructure development on the continent, particularly trade facilitation infrastructure. This includes hard infrastructure such as ports and harbours, road networks, rail networks, airports, border posts and customs facilities, special economic zones and industrial parks, and energy infrastructure. It also includes soft infrastructure such as payment systems, other financial services and information and communication technology. A report by the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA) estimated that the implementation of the AfCFTA would increase the demand for intra-African freight by 28% (UNECA, 2023).

These challenges have amplified the calls for private sector investment in infrastructure development in Africa. This is happening for a few reasons. The private sector is perceived to have better access to private capital when compared with governments: The sector is better able to prepare bankable investment projects, bring on board innovation, efficiency and expertise, and can help reduce the fiscal burden on governments. Models such as public-private partnerships are also regarded as sustainable as they combine the expertise of public and private sector actors. However, several challenges face private sector involvement in infrastructure investment in Africa. One of the major challenges is access to finance due to high costs, risk perception, currency risks, weak financial markets and lack of suitable financing instruments.

However, one source of infrastructure finance remains largely untapped by African private-sector actors. These are what are sometimes referred to as ‘geopolitical funds’. Geopolitical funds are financial resources allocated by a state, group of states, or international institutions, primarily driven by strategic geopolitical objectives. These funds are often used to influence or shape political, economic and social dynamics in specific regions or countries to align with the strategic interests of the funding entity. This category of funds includes China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the European Union’s Global Gateway Initiative (GGI) and the G7’s Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII).

This policy brief explores the opportunities for greater private sector involvement in the financing and development of trade facilitation infrastructure in Africa and the role geopolitical funds can play in this. Although some of these funds have been created precisely to respond to infrastructure needs in the developing world, it has been historically challenging to match African infrastructure projects with finances, with the main reason being cited as the projects’ ‘bankability’ (Pleeck & Gavas, 2023). The exploration conducted by this brief is therefore critical, given that some of these funds have set investment targets that can simply be missed by using the excuse of a lack of sufficient bankable projects. Increased private sector involvement on the African side will be crucial to mobilising the resources promised by these funds to support the development of trade infrastructure in Africa.

Understanding the AfCFTA's infrastructure needs

The AfCFTA seeks to increase the trade of goods and services produced in Africa among African countries. It will do this by gradually eliminating tariffs on up to 97% of goods produced and traded in Africa and by addressing the non-tariff barriers hindering intra-African trade. A number of studies have found that removing non-tariff barriers will have a more significant impact than eliminating tariffs on the growth of intra-African trade. For example, a study by the World Bank found that non-tariff trade costs in Africa are equivalent to 292% tariffs levied on the value of the goods (UNESCAP-World Bank, 2023). Transportation and other infrastructure costs are a core component of these non-tariff trade costs. Table 1 below lists some of the hard and soft infrastructure needs under the AfCFTA.

Table 1: Some infrastructure needs under the AfCFTA

| Type | Category | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Hard Infrastructure | Transportation Infrastructure |

|

| Energy Infrastructure |

|

|

| Telecommunications Infrastructure |

|

|

| Water and Sanitation |

|

|

| Industrial Infrastructure |

|

|

| Soft Infrastructure | Trade Facilitation Mechanisms |

|

| Data and Information Systems |

|

|

| Legal and Regulatory Frameworks |

|

|

| Financial Infrastructure |

|

|

| Human Capital Development |

|

|

| Institutional Capacity Building |

|

Notes: Author’s Construct 2024

In addition to the list in Table 1 above, the global fight against climate change means that the response to the infrastructure needs under the AfCFTA will need to include environmental considerations, including sustainable transport networks, green energy infrastructure, eco-friendly industrial zones, digital infrastructure for trade efficiency, sustainable agriculture infrastructure and climate-resilient urban infrastructure. The need for climate-resilient or mitigating trade infrastructure widens the infrastructure financing gap and reduces the ability of governments to fill it.

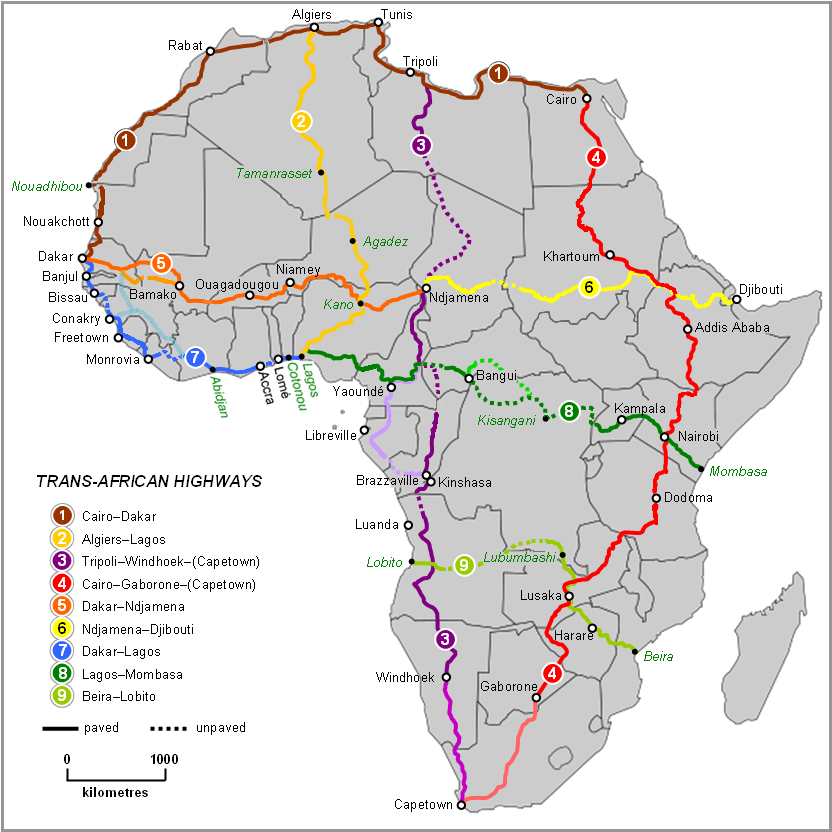

There are ongoing integrated infrastructure interventions in Africa to facilitate cross-border trade. Some critical trade corridors have been identified with efforts to mobilise investment. Table 2 lists some of these corridors and Figure 1 shows the Trans-African Highway Network which includes some of the listed corridors. Although the network was first conceived in 1971, there has been some progress in its execution.

Table 2: Some transport corridors in Africa

| North Africa |

|

|---|---|

| West Africa |

|

| Central Africa |

|

| East Africa |

|

| Southern Africa |

|

Note: Author’s Construct, 2024

Figure 1: Trans-African Highway Network. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Some challenges facing infrastructure development under the AfCFTA

There are a number of challenges facing the development of sustainable critical infrastructure needed for the successful implementation of the AfCFTA. These include:

- High capital requirements: The scale of investment required for comprehensive infrastructure development across Africa is immense. This includes the cost of building new infrastructure and upgrading existing facilities.

- Risk perception: Africa is often perceived as a high-risk investment destination due to factors like political instability, economic volatility and currency fluctuations (Gbohoui et al., 2023). This perception can deter investors and increase the cost of capital (Hassan, 2023).

- Limited domestic funding and high public debt levels: Many African countries have limited domestic financial resources due to smaller economies, lower savings rates and constrained fiscal budgets. High public debt levels also restrict their ability to finance infrastructure projects through public borrowing (David & Eyraud, 2023).

- Lack of bankable projects: There is a reported shortage of well-prepared, bankable infrastructure projects. Many projects do not progress beyond the feasibility stage due to poor project preparation and unclear investment returns (McKinsey, 2020).

- Inadequate Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs): While PPPs are crucial for infrastructure financing, many African countries lack the necessary legal and regulatory frameworks, as well as the institutional capacity to effectively implement and manage them (Kilangi, 2021).

- Foreign exchange risks: Given that much of the funding needs to be sourced internationally, there is a risk associated with foreign exchange fluctuations, especially in countries with volatile currencies (Rogoff & Reinhart, 2003).

- Insufficient integrated regional planning: Effective regional planning is required to ensure that infrastructure projects across different countries are harmonised and mutually beneficial (Hagerman, 2012).

- Inadequate risk mitigation instruments: There are insufficient mechanisms to mitigate risks associated with infrastructure projects, such as political risk insurance and currency risk management tools (McKinsey, 2020).

- Capacity constraints: Many African countries have limited technical and managerial capacity to plan, develop and implement large-scale infrastructure projects (McKinsey, 2020).

- Governance and transparency issues: Issues related to governance and transparency in project tendering and implementation can deter potential investors due to concerns over corruption and mismanagement (McKinsey, 2020).

These challenges, coupled with the challenging fiscal environment facing many African governments, have slowed the process of addressing critical infrastructure needs (McKinsey, 2020). This is despite the fact that regional actors such as the African Union, the African Development Bank and the African Export Import Bank (AfreximBank) are playing a role in the development of this infrastructure. The African Union has launched plans such as the Program Infrastructure Development for Africa (PIDA)1 and is the champion of the Trans-African Highway Network. The AfDB has invested heavily in regional infrastructure development, and AfreximBank is managing a USD 1 billion Adjustment Fund for the AfCFTA that may also invest in infrastructure.

However, the combination of these efforts has been insufficient to reduce the annual infrastructure financing gap of USD 68 - 108 billion. This implies that innovative ways must be found to fund critical infrastructure to facilitate trade under the AfCFTA. One actor that could fill the funding gap is the private sector. Some efforts have already been made to scale up private sector participation in critical infrastructure provision. Table 3 below compiles some funds and initiatives with this goal.

Table 3: Some initiatives targeted at increased private sector participation

| Programmes and Initiatives | Responsible | |

|---|---|---|

| Continental | Programme for Infrastructure Development in Africa (PIDA) | African Union |

| Africa50 Fund | African Development Bank | |

| Infrastructure Project Preparation Facility (IPPF) | New Partnership for Africa's Development (NEPAD) (African Union) |

|

| African Legal Support Facility (ALSF) | African Development Bank | |

| African Infrastructure Investment Managers (AIIM) | Private organisation | |

| Capital Mobilization and Partnerships Department (and other diverse initiatives)2 | African Finance Corporation (AFC) | |

| Africa50 Infrastructure Acceleration Fund | International Finance Corporation | |

| Private Sector Investment Lab | World Bank | |

| Regional | Public-Private Partnership (PPP) Network | Southern African Development Community (SADC) |

| Public-Private Partnership (PPP) Bill | East African Community (EAC) | |

| Public-Private Partnership (PPP) Initiatives | West African Development Bank (BOAD) | |

| Africa Investment Forum | African Union and the African Development Bank | |

| Smart Africa Initiative | ||

| National | At the national level, most economic development plans include provisions for encouraging private sector involvement in the development of critical infrastructure. |

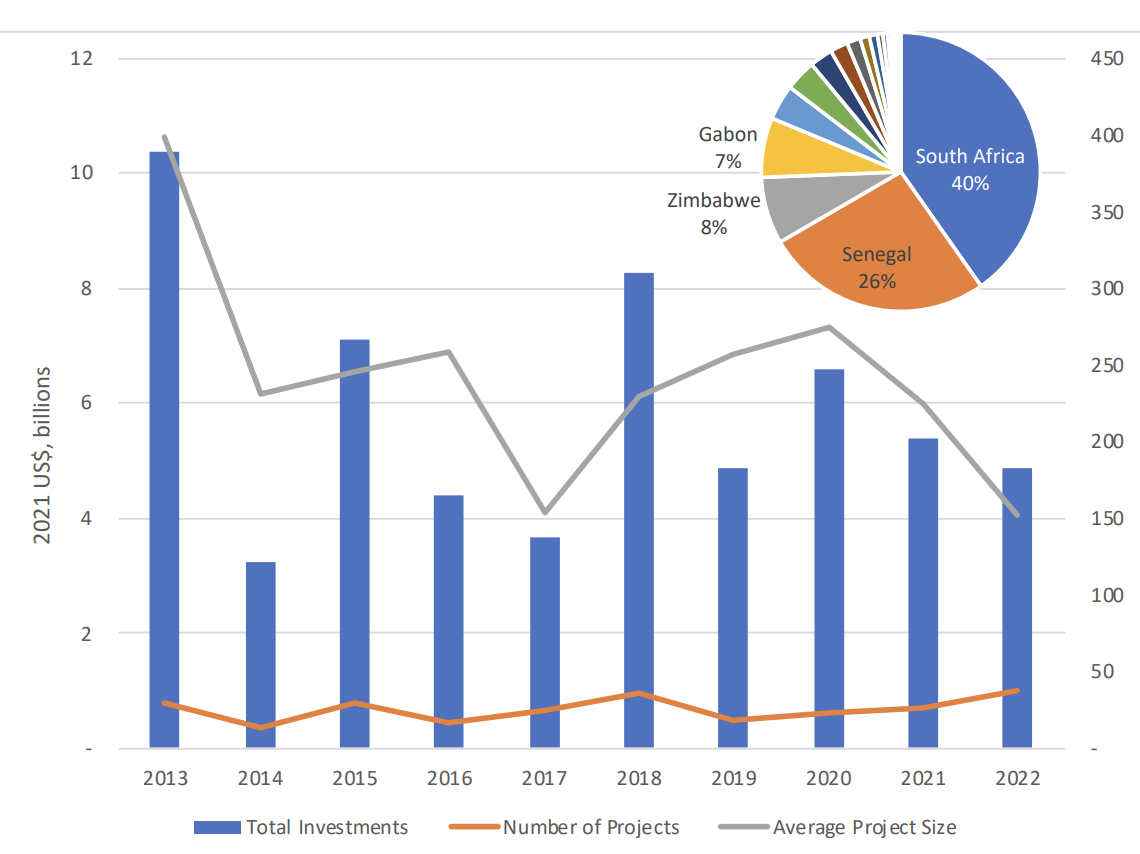

However, according to the World Bank’s (2022) Private Participation in Infrastructure database, the volume of infrastructure investments that include private sector involvement in Africa is still low and has failed to reach the 2013 USD 10 billion high, as shown in Figure 2 below.

The implication of the analysis in this section is that there is a need for more innovative approaches to increasing private sector involvement in trade infrastructure development across the continent. Approaches should also target both the investing organisations and their potential sources of capital. One such source is geopolitical infrastructure funds. The sections below discuss this in detail.

Figure 2:

Investment commitments in infrastructure projects with private participation in low- and middle-income countries in SSA, 2013–2022, and PPI shares by country in 2022.

Critical overview of international funding initiatives

Geopolitical infrastructure funds, typically mobilised by powerful states or coalitions, aim at economic returns and achieving strategic geopolitical outcomes. They serve as tools for fostering diplomatic ties, expanding economic influence and sometimes countering the influence of rival geopolitical powers. In the context of Africa, these funds have increasingly become a cornerstone for financing critical infrastructure in the transport, energy, telecommunications and water sectors. Other initiatives include the British government's African Infrastructure Investment Fund (AIIF3) and the G20’s Global Infrastructure Facility (GIF).

This section explores three main global geopolitical funds, focusing on their implications and potential for Africa's trade infrastructure development. These funds include China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the European Union's Global Gateway Initiative and the G7’s Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGI) plan. These three funds have been selected because they have been designed to further the soft power of their administrators or to counter the growing influence of other countries. Each of these initiatives presents unique opportunities, challenges and strategic considerations for African countries, aligning with the broader objective of enhancing trade infrastructure under frameworks such as the AfCFTA.

The analysis will highlight the opportunities these funds present for Africa, the caveats and strategic considerations African private sector actors must reckon with, and the potential alignment of these funds with Africa’s infrastructure and trade goals. Understanding the dynamics of these geopolitical funds is crucial for African policymakers, investors and private sector entities looking to capitalise on these opportunities while navigating their complexities.

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)

Since its inception in 2013, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has grown into a vast network of infrastructure projects spanning several continents, with a significant focus on Asia, Africa and Europe. As of 2023, the initiative includes over 200 cooperation agreements that have been signed with 150 countries and 30 international organisations, underlining China's global ambitions (The State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, 2023). The BRI encompasses a wide range of infrastructure projects, such as highways, railways, ports and power plants, and has played a crucial role in enhancing connectivity and infrastructure development in participating countries. BRI projects are based on five priorities: policy coordination, facilities connectivity, unimpeded trade, financial integration and people-to-people bond (Feingold, 2023). However, at its core, the BRI is a geopolitical fund meant to further China’s foreign policy and soft power ideals. Beyond increasing global connectivity, its overarching aim is to strengthen and consolidate China’s influence in the world.

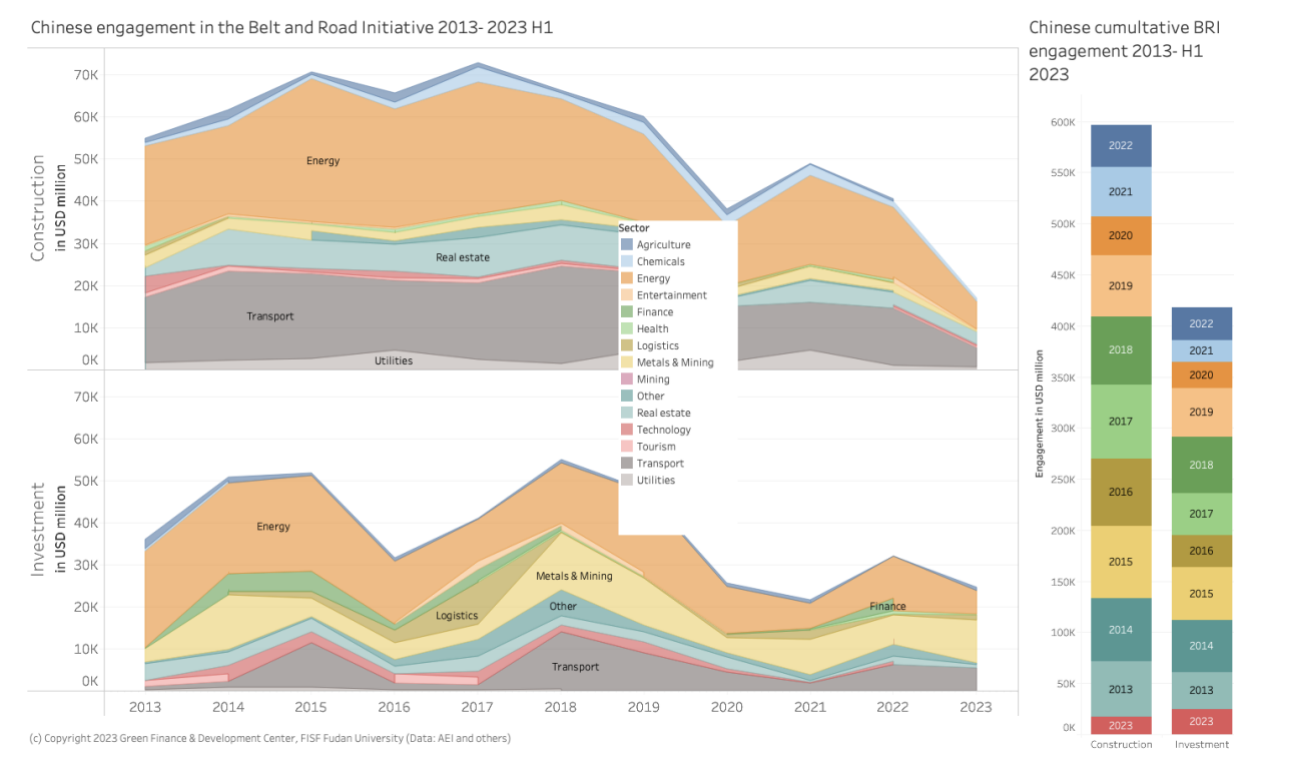

It has been estimated that since its launch, total BRI engagement has exceeded USD 1 trillion, including USD 596 billion in construction contracts and USD 420 billion in non-financial investments (Nedopil, 2023). Figure 3 shows these engagements have been in a wide range of sectors, including transport and logistics. Estimates of total BRI engagements in Africa are difficult to find. However, Chinese companies are reported to have signed USD 700 billion in construction contracts in the last ten years and completed an estimated project turnover of USD 400 billion (CGTN, 2023). According to the Chinese Loans to Africa Database (2023), from 2013 to 2022, China committed around USD 114.4 billion of loans to African countries. Over the past decade, China has assisted in building over 6,000 kilometres of railways and roads, around 20 ports, more than 80 major power facilities and over 130 hospitals and 170 schools in African countries (CGTN, 2023).

Figure 3:

Chinese engagement in the Belt and Road Initiative 2013 - 2023 H1.

Embedded in the provisions of the BRI are measures that encourage private sector involvement in infrastructure development. The Chinese private sector is already heavily involved in the financing and execution of infrastructure projects: As of 2019, it was reported that 274 out of the top 500 firms in China were participating in the BRI (Xinhua, 2019). The initiative has also sought the participation of private sector actors across the world and encourages public-private partnerships for infrastructure development. In addition, it supports the development of special economic zones, which are sometimes private investments. The BRI is, therefore, technically a key source of financing for African private sector actors that are seeking to be involved in the development of trade facilitation infrastructure. This is already the case with a project based in Nigeria, as Figure 4 shows.

Figure 4:

BRI trade facilitation project in Nigeria

|

| The Lekki Deep Sea Port started full commercial operations in Lagos, Nigeria in April 2023. It is one of the major BRI projects in Nigeria and was executed as a collaboration between Tolaram Nigeria in partnership with the China Harbour Engineering Company. These two formed an international consortium led by Lekki Port Investment Holding and were awarded the concession for 45 years by the Nigerian Ports Authority on a Build, Own, Operate and Transfer (BOOT) basis. The shareholding structure for the port includes China Harbour Engineering Company (52.5%), Tolaram (22.5%), the Lagos State Government (20%) and the Nigerian Ports Authority (5%).3 It is expected to have an aggregate impact of USD 361 billion over its 45 years concession period. |

Note: Image source: CNN

The Global Gateway Initiative (GGI)

On different platforms, EU leaders have expressed concerns about China’s growing reach and influence in the developing world through its large infrastructure development deals. The Global Gateway Initiative (GGI) is therefore regarded as the European Union’s (EU) response to China’s BRI (Seibt, 2021). The GGI was launched in December 2021 as a EUR 300 billion fund, with half dedicated to Africa from 2021 - 2027. Its focus is soft and hard infrastructure for improved global connectivity, and it is administered by the European Investment Bank. A significant portion of the fund will be mobilised from EU private sector stakeholders, making the EUR 300 billion more of a fundraising target.

The GGI has faced a lot of criticism including assertions that its size is too small, and observations that it includes ‘old’ repackaged projects that were already planned by EU-member states (Barbero, 2023). The initiative also experienced some implementation delays due to the emergence of the Russia-Ukraine conflict in Europe. However, the GGI has since announced key flagship projects in the developing world, including in Africa.

Also embedded in the structure of the GGI is a prioritisation of private sector involvement. Again, on the European side, there is an intention to mobilise a large portion of GGI funds from the private sector. The fund also allows for the participation of private sector actors on the side of recipient countries in a B2B model for investment. It is unclear to what extent this opportunity has been explored by African private sector actors, but there is immense potential for leveraging the GGI for resource mobilisation around trade infrastructure development. Table 4 below lists some African infrastructure projects related to trade facilitation that have already received GGI commitments.

The Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGI)

The Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGI) was formally launched by the United States President Joe Biden and other G7 leaders in 2022. It aims to mobilise USD 600 billion in investment and provide support in four primary areas: climate and energy security, digital connectivity, health systems and health security, and gender equality and equity. The PGI emphasises a values-driven, high-standard and transparent approach to infrastructure investment, focusing on delivering quality, sustainable projects that can make a meaningful difference in people’s lives globally. It also seeks to strengthen and diversify supply chains, which is expected to positively impact the global economy and resilience to global energy and supply chain challenges.

The PGI is a rebrand and evolution of the Build Back Better World (B3W) initiative launched in 2021 by the United States to focus on infrastructure financing in developing countries. It is also regarded as the US and G7’s response to Chinese-led infrastructure development in the developing world. This aligns the PGI with the GGI; both funds have even collaborated on the Lobito Corridor trade infrastructure investment in Africa. Like the other initiatives discussed, the PGI includes a strong private sector component, targeting these actors as a source of a large percentage of the financing targets. A PGI factsheet on the US White House website overtly states: ‘Through PGI, the United States welcomes public and private sector stakeholders leveraging their expertise and networks to advance complex transactions and strategic joint ventures to drive quality infrastructure investments in low- and middle-income countries’. As shown in Figure 5, there are already ongoing collaborations between African private sector actors and the PGI. There is therefore an opportunity for wider participation by private sector actors, particularly in providing trade infrastructure in Africa.

Figure 5:

PGI investment commitment to Africa Data Centres

|

| Africa Data Centres is a business owned by Cassava Technologies and has built the largest network of interconnected, carrier- and cloud-neutral data centre facilities. It has also built Africa’s largest independent fibre network, stretching more than 73,000km. It was announced in May 2023 that Africa Data Centres will receive a USD 300 million loan under the PGI to construct a world class data centre in Ghana. |

Note: FACT SHEET: Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment at the G7 Summit.

Table 4: Summary of discussed geopolitical funds

| Fund | Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) | Global Gateway Initiative (GGI) | Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Originator | China | European Union | G7 countries (led by the United States) |

| Launch year | 2013 | 2021 | 2022 |

| Scope | Global | Africa, Asia and the Pacific, Latin America and the Caribbean | Low- and middle-income countries |

| Focus areas |

|

|

|

| Global target | Not available | EUR 300 billion (2021 - 2027) | USD 600 billion (USD 200 billion by the United States) (2022 - 2027) |

| Africa target | Not available | EUR 150 billion | |

| Commitments | USD 1 trillion (2013 - 2023) | EUR 66 billion 4 | |

| Principles |

|

|

|

| Sample trade infrastructure projects | Lekki Deep Sea Port |

|

|

Leveraging geopolitical funds for private sector-led trade infrastructure development

The overview of the selected geopolitical funds presented in the previous section repeatedly highlighted their suitability for private-sector involvement. On the side of the fund administrators, investment targets have been set, and plans have been made to mobilise resources from their private sector actors. This is particularly the case for the GGI and the PGI. The BRI contains a larger proportion of state funds but invites the Chinese private sector to participate in the execution of the projects. The emphasis on private-sector cooperation presents an opportunity for African private-sector actors seeking to develop trade infrastructure.

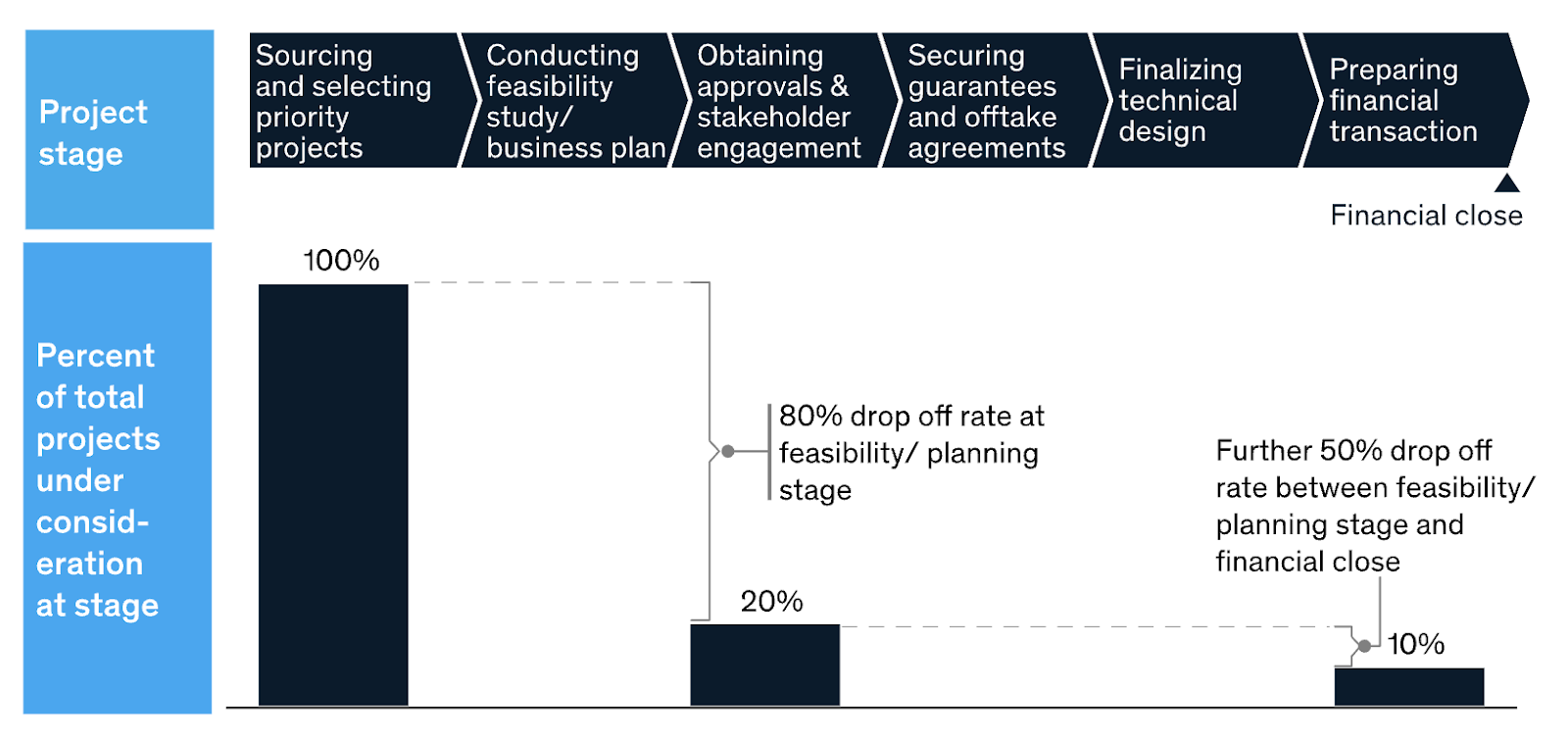

However, the emphasis on private capital is also a challenge for the funds. Mobilising private finance for what will essentially be development projects is a tall task, given the expectations of profit. African trade infrastructure projects can be profitable, but this will often be in the long term. There has also been negligible growth in private finance for development projects (OECD, 2023). Linked to this is the fact that private investors have stricter requirements for the projects they select, and African infrastructure projects are sometimes regarded as not being feasible. From a global perspective, an analysis by the World Bank asserts that although there is technically sufficient capital to address global infrastructure needs, the challenge is the bankability of these projects (Zelikow & Savas, 2022). At an estimated USD 1.2 trillion in 2022, the current pipeline of investable greenfield projects (many of which will not be ready in the short-term) in emerging markets is less than half of the estimated annual need of USD 2.6 trillion (Zelikow & Savas, 2022). A report by McKinsey (2020) showed that less than 10% of African infrastructure projects reach financial close and 80% of projects fail at the feasibility and business plan stage.

Figure 6: Drop off in feasibility of African infrastructure projects

The challenge lies in the preparation of packaging of African infrastructure projects in ways that deem them bankable to private investors. This often demands close coordination with governments, which sometimes presents a hurdle for private sector led projects (Pleeck & Gavas, 2023), since most African governments and investment agencies are not equipped for such action. However, this challenge presents several opportunities for African private sector actors leveraging geopolitical funds and strengthens the case for their increased involvement in infrastructure projects. Some of these opportunities are listed below.

Opportunities

- Access to large-scale financing: Geopolitical funds, including the BRI, GGI and PGI, offer significant financing opportunities. These funds are designed to mobilise vast resources, providing a substantial financial base for private sector-led infrastructure projects.

- Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs): Geopolitical funds' emphasis on PPPs opens avenues for private sector entities to engage in large-scale projects. PPPs can mitigate risk, leverage public sector strengths and benefit from private sector efficiency and innovation.

- arket expansion and diversification: For African private sector actors, participating in BRI, GGI or PGI projects can offer access to new markets and opportunities for diversification. This exposure can be crucial for business growth and resilience.

- Technology and knowledge transfer: Collaborating on international projects under these funds can facilitate technology and knowledge transfer. This aspect is particularly beneficial for the African private sector, which often seeks advanced technological inputs and expertise.

- Enhanced global visibility and credibility: Involvement in high-profile projects funded by major international initiatives can enhance the global visibility and credibility of African private sector companies.

- Capacity building: Geopolitical funds often come with capacity-building components, helping to strengthen the institutional and operational capabilities of private sector entities in Africa.

- Addressing infrastructure gaps: By participating in these initiatives, the African private sector can play a direct role in addressing the continent's critical infrastructure gaps, fostering regional trade and connectivity in the context of the implementation of the AfCFTA.

- Sustainable development: Many of these funds have a focus on sustainable and environmentally friendly projects, aligning with global sustainable development goals and providing opportunities for African businesses to engage in green initiatives.

Despite the opportunities presented by geopolitical funds, there are challenges that will need to be addressed.

Challenges

- Dependency and debt sustainability: Dependency on external funding and the risk of increasing debt burdens for host countries are significant concerns. This can impact the long-term economic sustainability of the African private sector and the host countries. Although geopolitical funds have grant components, they are often provided in the form of loans to governments or private sector actors. Infrastructure development projects that rely on this kind of funding often face a greater risk profile compared to those financed entirely through private means. This heightened risk is due to the complex nature of these projects, which, without government support, might not meet the traditional criteria for investment attractiveness or bankability. As one example, debt sustainability is regarded as one of the reasons why Chinese lending through the BRI has declined (Dezenski & Birenbaum, 2024). Countries like Djibouti and Zambia have accumulated debts to China equivalent to at least 20% of their annual GDP. In Djibouti’s case, Chinese debt is around 45% of its GDP (African Defense Forum, 2023). These debts are often tied to large infrastructure projects, leading to concerns about debt sustainability and the potential for ‘debt traps’.

- Contract terms and conditionalities: Due to restrictive contract terms, Chinese lending practices have drawn criticism. For instance, Chinese state-owned lenders often require borrowers to maintain a minimum cash balance in an offshore account accessible to the lender (Gelpern et al., 2021). This can limit the financial flexibility of private sector entities and expose them to undue leverage by the lender. Some countries receiving Chinese aid have become dependent on China in strategic economic sectors due to Chinese-dominated investments, leading to institutionalised dependency. There is also the challenge of cross-conditionality through Chinese bank funding that often gives China leverage over recipient nations, allowing them to impose additional demands outside aid and loan agreements. This includes cutting off funds if recipients do not meet further conditions. There are also sometimes confidentiality clauses that impact the transparency of the agreements. Another related issue is that some geopolitical loans stipulate the use of machinery and contractors from the lending countries, something referred to as ‘tied-aid’ (Sun, 2014). This requirement can increase project costs and dependency on foreign entities, reducing the potential for local capacity building and technology transfer.

- Awareness and accessibility: A major challenge for African private sector actors is the lack of awareness about geopolitical funds. While these funds are well-known in the international development space, they are not as widely recognised in the African business and private sector circles. This lack of awareness hinders the ability of local businesses to seek and utilise these funding opportunities. Even when aware, accessing these funds can be daunting due to complex application processes, stringent eligibility criteria and a lack of resources or expertise to navigate these processes effectively. For example, internet search results for these funds provide little to no information about the process for accessing them. This is partly because they are often negotiated between governments with limited involvement of the domestic private sector. This difficulty serves as a barrier to private sector involvement in infrastructure financing.

- Red tape and bureaucracy: The bureaucratic challenges associated with international funding - including extensive documentation, strict compliance requirements and long approval processes - can be significant barriers, especially for smaller enterprises. A report by the OECD (2017) highlighted how bureaucratic obstacles and regulatory complexities can impede investment flows into Africa, suggesting that simplification of procedures and enhanced transparency are critical for improving access to funding.

- Sustainability concerns: A significant risk associated with leveraging geopolitical funds like the BRI is sustainability, which encompasses environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues. Notably, the AidData report (2021) found that roughly 35% of BRI projects faced challenges like environmental incidents and labour violations. The BRI has since adopted a ‘green’ agenda, and sustainability was embedded into the design of the GGI and PGI. The focus on sustainability issues underlines the importance of incorporating ESG criteria in project planning and implementation to ensure that development efforts are both impactful and sustainable. However, it also means that private sector actors looking to access these funds will need to be able to demonstrate the sustainability of their projects. Meeting the high international standards required by these funds can be a significant challenge for local firms, particularly those with limited experience in such areas.

- Geopolitical dimensions: The strategic interests of funding countries often influence the allocation of geopolitical funds. The aggression by Russia in Ukraine, for example, has highlighted a change in Western development policy. Now, issues of development are intertwined more than before with geopolitical and geoeconomic concerns, such as the security of energy and raw materials (Klingebiel, 2023). This can create alignment challenges, where projects may be selected based on their geopolitical significance rather than the developmental needs of African countries. The disproportionate focus on strategic minerals is one example of this.

- Unstable macroeconomic environments: Unstable macroeconomic conditions in African countries, such as currency fluctuations, policy changes and economic volatility can adversely impact the viability and returns on investment for infrastructure projects. A study by Chinzara et al. (2023) found a negative impact of macroeconomic instability on PPI. As one example, Julius Berger Nigeria, an infrastructure development firm, has suffered financial losses due to the unstable foreign exchange market in Nigeria (Tokede, 2023). Infrastructure investments are particularly sensitive to macroeconomic fluctuations due to their long-term nature.

- Collaboration challenges with governments: Private sector entities may face challenges in collaborating with governments on infrastructure projects. These can include bureaucratic delays, policy uncertainties and difficulties in aligning project objectives with governmental agendas. There is also the challenge of bounded rationality, especially in the context of public-private partnerships where both actors agree to contractual terms that may not sufficiently take into consideration future risks and threats. These collaboration challenges can contribute to the failure of infrastructure development projects. A report by the United Nations Trade and Development (UNCTAD, 2016), using World Bank data, states that about 60 PPP projects valued at USD 1 billion have been cancelled in Africa.

Promoting African agency in trade infrastructure development - recommendations

As Africa continues to navigate the complexities of global trade and infrastructure development, it is imperative to focus on promoting African agency in these spheres. The dynamic nature of international investments, especially in the context of initiatives like the BRI, GGI and PGI presents both opportunities and challenges for the continent. This section explores strategies and policy recommendations that can empower African entities – governments, private sectors and civil societies – to assert their interests more effectively in project negotiations and engagements. The goal is to move beyond just being recipients of international investments to becoming active, informed participants who can shape the outcomes in ways that align with the continent’s developmental goals and priorities. By bolstering negotiation capacities, refining project selection processes and formulating supportive policies, African stakeholders can ensure that trade infrastructure developments are not only economically beneficial but also socially equitable and sustainable. At the centre of these strategies is elevating the role of the African private sector as a conduit for geopolitical funds for infrastructure development. The private sector has capacities that can improve African agency in the utilisation of these funds, and their involvement should therefore be promoted.

The following recommendations are being put forward to help increase the participation of the private sector in trade infrastructure development under the AfCFTA by facilitating their access to geopolitical funds.

For African governments

- Develop comprehensive infrastructure strategies: Align national infrastructure plans with AfCFTA goals, ensuring projects enhance regional connectivity and trade. This approach should prioritise high-impact projects that offer significant returns in terms of trade facilitation and economic integration.

- Diversification of funding sources: To avoid over-reliance on any single source of funding, African countries should diversify their sources of infrastructure financing. This includes exploring alternative funding mechanisms such as domestic resource mobilisation, public-private partnerships and regional funding initiatives.

- Strategic project selection: Project selection for geopolitical funds should also be done in partnership with private sector actors. There is also a need to allocate resources for developing comprehensive feasibility studies and business plans to increase the bankability of projects and attract more private investment.

- Increased private sector engagement: Existing platforms should be strengthened, and the private sector should be involved at the early stages of multilateral negotiations. Enabling environments for PPPs should be created by offering incentives, streamlining regulatory processes and providing guarantees to mitigate risks for private investors.

- Improve institutional capacity: There is a need to strengthen the capacity of public institutions for project development and management and ensure effective utilisation of geopolitical funds. There is also a need to enhance governance structures and financial transparency to increase investor confidence. Clear legal frameworks for infrastructure investments and dispute resolutions should be established.

For the African private sector

- Invest in geopolitical expertise for resource mobilisation: Understanding the intricacies of global geopolitics is pivotal for African entities looking to engage in trade infrastructure development. This involves developing a nuanced understanding of the geopolitical interests and strategic goals of various international actors and funders, including the motivations behind initiatives like the BRI, the GGI and the PGI. African entities should invest in acquiring expertise on how geopolitical dynamics influence funding decisions and project approvals. They should also clearly understand the conditionalities, risks and trade-offs that come with leveraging these funds. This knowledge can be pivotal in crafting proposals and negotiation strategies that align with the interests of funders while safeguarding Africa's developmental objectives. There is also a need to develop robust negotiation skills to better navigate the terms of geopolitical funds. This includes advocating for more favourable contract terms that minimise undue leverage and promote financial flexibility.

- Invest in comprehensive project preparation: It is essential for African entities to allocate substantial resources to the early stages of project development. This includes conducting thorough feasibility studies, market analyses and environmental impact assessments. Ensuring that projects are technically and financially sound is crucial for attracting investment. Detailed financial modelling, exploring various funding mechanisms, and assessing long-term economic viability should be integral parts of the planning process.

- Form strategic alliances: Consortiums and alliances should be built to enhance capabilities and increase competitiveness in accessing and executing large-scale infrastructure projects. Consortiums should not only include national firms but also regional firms in other African countries. This will be essential for cross-border infrastructure development.

- Strengthen government relations: Although governments can be tricky to navigate, they cannot be taken out of the equation for major infrastructure projects. Geopolitical funds in particular will require governments to be engaged one way or the other. There is a need for private sector actors to build their capacity to collaborate with governments while being pragmatic about the limitations and risks this presents.

- Leverage international partnerships: There is a need to engage with international partners for knowledge transfer, technical assistance and co-financing opportunities. Partnerships with organisations domiciled in the countries that control these funds will be one way to improve the accessibility of the funds.

- Focus on sustainable and inclusive projects: These geopolitical funds are not intended solely for profit-making ventures, they also target sustainable development goals. There is therefore a need to align projects with these goals and ESG standards, ensuring projects are environmentally sound and socially inclusive.

For geopolitical fund owners

- Align investments with local priorities: Despite the geopolitical incentives behind the funds, there is a need to ensure that funded projects align with the priorities and needs of African countries, particularly in supporting the objectives of the AfCFTA.

- Provide targeted technical assistance: Fund owners should offer technical support in project preparation, feasibility studies and capacity building for local entities to enhance the quality and success rate of infrastructure projects.

- Innovative financing models: There is a need to further strengthen financing models that reduce risk and increase attractiveness for private investors, such as blended finance or risk-sharing instruments.

- Increase engagement and presence on the ground: Fund owners should consider strengthening local offices to foster closer collaboration with African governments and private sector entities and to gain a better understanding of local contexts and needs. There is also a need to more transparently share information on the modalities of access to these funds for interested private sector actors.

For intermediary organisations (including development finance institutions such as the World Bank and the AfDB and other multilateral institutions)

- Facilitate access to information and training: Intermediary organisations can provide African entities (both public and private) with information on available funds and training on how to access and manage these funds effectively.

- Broker partnerships between stakeholders: These organisations are well positioned to act as intermediaries to connect African private sector entities with geopolitical fund owners and government projects.

- Support project preparation and development: These organisations can also assist in the preparation and development of infrastructure projects to meet the standards required by international investors and funders. This will also include providing guidance on managing various risks associated with large-scale infrastructure projects.

- Advocate for enabling policies: There is a need to work with governments to advocate for and implement policy reforms that create a conducive environment for private sector investment in infrastructure. This can draw on best practices observed in the global context that are tailored to domestic realities.

Conclusion

This paper has explored the multifaceted landscape of trade infrastructure development in Africa, with a particular focus on the role of private sector involvement and the leveraging of geopolitical funds. The analysis underscores the criticality of infrastructure in bolstering Africa's economic growth and the pivotal role of the AfCFTA in this context. While opportunities abound, particularly through initiatives like the BRI, GGI and PCI, challenges such as lack of bankable projects, bureaucratic hurdles and geopolitical complexities persist.

To navigate these challenges, a collaborative approach involving African governments, private sector entities, geopolitical fund owners and intermediary organisations is imperative. African governments are tasked with creating enabling environments and aligning infrastructure development with continental trade goals. The private sector, on the other hand, must actively engage in early project stages and form strategic alliances to leverage these opportunities effectively. Furthermore, the role of geopolitical fund owners and intermediaries in fostering transparent, accessible and sustainable funding mechanisms cannot be overstated.

The successful implementation of these recommendations hinges on a balanced synergy between global investment strategies and Africa's development aspirations. As such, the continent's journey towards robust and sustainable trade infrastructure development, underpinned by private sector dynamism and supported by strategic international investments, is not only feasible but imperative for its economic transformation.

References

African Defense Forum. (2023). Inflation, Drought Push Djibouti to Suspend Loan Payments to China. ADF Magazine. Retrieved from https://adf-magazine.com/2023/01/inflation-drought-push-djibouti-to-suspend-loan-payments-to-china/

African Development Bank. (2023). Africa’s Infrastructure: Great Potential but Little Impact on Positive Growth. Retrieved from https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Publications/2018AEO/African_Economic_Outlook_2018_-_EN_Chapter3.pdf

African Union. (2023). African ministers commit to accelerate infrastructural development to boost Africa's competitiveness and participation in global market. Retrieved from https://au.int/en/pressreleases/20230921/african-ministers-commit-accelerate-infrastructural-development-boost-africas

Afrobarometer. (2024). Water and sanitation still major challenges in Africa, especially for rural and poor citizens. Retrieved from https://www.afrobarometer.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/AD784-PAP11-Water-and-sanitation-still-major-challenges-across-Africa-Afrobarometer-19march24.pdf

Barbero, M. (2023). Europe Is Trying (and Failing) to Beat China at the Development Game. Foreign Policy. Retrieved from https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/01/10/europe-china-eu-global-gateway-bri-economic-development/

Boston University Global Development Policy Center. (2023). Chinese Loans to Africa Database. Retrieved from http://bu.edu/gdp/chinese-loans-to-africa-database

Chinzara, Z., Dessus, S. & Dreyhaupt, S. (2023). Infrastructure in Africa: How Institutional Reforms Can Attract More Private Investment. International Finance Corporation. Retrieved from https://www.ifc.org/content/dam/ifc/doc/2023/working-paper-infrastructure-in-africa.pdf

CGTN. (2023). Graphics: How Belt and Road has impacted China-Africa cooperation. Retrieved from https://news.cgtn.com/news/2023-06-29/Graphics-How-Belt-and-Road-has-impacted-China-Africa-cooperation-1l1r5Od5wys/index.html

David, A., & Eyraud, L. (2023). Navigating Fiscal Challenges in Sub-Saharan Africa: Resilient Strategies and Credible Anchors in Turbulent Waters. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved from https://www.imf.org/-/media/Files/Publications/DP/2023/English/APCFSFSSACEA.ashx

Dezenski, E. K. & Birenbaum, J. (2024). Tightening the Belt or End of the Road? China’s BRI at 10. Foundation for Defense of Democracies. Retrieved from https://www.fdd.org/analysis/2024/02/27/tightening-the-belt-or-end-of-the-road-chinas-bri-at-10/

FACT SHEET: Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment at the G7 Summit. White House. Retrieved from https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2023/05/20/fact-sheet-partnership-for-global-infrastructure-and-investment-at-the-g7-summit/

Feingold, S. (2023). China’s Belt and Road Initiative turns 10. Here’s what to know. World Economic Forum. Retrieved from https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2023/11/china-belt-road-initiative-trade-bri-silk-road/

Gbohoui, W., Ouedraogo, R., & Some, Y. M. (2023). Sub-Saharan Africa’s Risk Perception Premium: In the Search of Missing Factors. IMF Working Papers. Retrieved from https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2023/06/23/Sub-Saharan-Africas-Risk-Perception-Premium-In-the-Search-of-Missing-Factors-534885

Gelpern, A., Horn, S., Morris, S., Parks, B., & Trebesch, C. (2021). How China Lends: A Rare Look into 100 Debt Contracts with Foreign Governments. Center for Global Development. Retrieved from https://www.cgdev.org/publication/how-china-lends-rare-look-into-100-debt-contracts-foreign-governments

Hagerman, E. (2012). Challenges to regional infrastructure development. Trade and Industrial Policy Strategies. Retrieved from https://www.tips.org.za/files/report_on_regional_infrastructure_development_in_africa_tips_-_ellen_hagerman.pdf

Hassan, A. S. (2023). Does country risk influence foreign direct investment inflows? Evidence from Nigeria and South Africa. Journal of Contemporary Management, 20 (1). Retrieved from https://journals.co.za/doi/pdf/10.35683/jcm22022.212

Kilangi, J. M. (2021). Address today’s challenges to build a sustainable long-term PPP strategy for Africa. World Bank Blogs. Retrieved from https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/ppps/address-todays-challenges-build-sustainable-long-term-ppp-strategy-africa

Klingebiel, S. (2023). Geopolitics, the Global South and Development Policy. German Institute of Development Policy and Sustainability. Retrieved from https://www.idos-research.de/uploads/media/PB_14.2023.pdf

Lakmeeharan, K., Manji, Q., Nyairo, R. & Pöltner, H. (2020). Solving Africa’s infrastructure paradox. McKinsey. Retrieved from https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/operations/our-insights/solving-africas-infrastructure-paradox

Malik, A., Parks, B., Russell, B., Lin, J., Walsh, K., Solomon, K., Zhang, S., Elston, T., & Goodman, S. (2021). Banking on the Belt and Road: Insights from a new global dataset of 13,427 Chinese development projects. Williamsburg, VA: AidData at William & Mary.

Moses, O., Hwang, J., Engel, L., and Bien-Aimé, V. Y. (2023). A New State of Lending: Chinese Loans to Africa. Boston University Global Development Centre. Retrieved from https://www.bu.edu/gdp/2023/09/18/a-new-state-of-lending-chinese-loans-to-africa/

Nedopil, C. (2023). China Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) Investment Report 2023 H1 – the first ten years. Green Finance & Development Center. FISF Fudan University, Shanghai. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/372788122_China_Belt_and_Road_Initiative_BRI_Investment_Report_2023_H1

OECD (2023). Mobilised private finance for sustainable development. Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-standards/mobilisation.htm

Pleeck, S. & Gavas, M. (2023). Bottlenecks in Africa’s Infrastructure Financing and How to Overcome Them. Centre for Global Development. Retrieved from https://www.cgdev.org/blog/bottlenecks-africas-infrastructure-financing-and-how-overcome-them

Revenue Statistics in Africa (2023). Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/tax/tax-policy/brochure-revenue-statistics-africa.pdf

Rogoff, K. & Reinhart, C. (2003). FDI to Africa: The Role of Price Stability and Currency Instability. IMF Working Paper. Retrieved from https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2003/wp0310.pdf

Seibt, S. (2021). With its ‘Global Gateway’, EU tries to compete with China’s Belt and Road Initiative. France24. Retrieved from https://www.france24.com/en/europe/20211203-with-its-global-gateway-eu-tries-to-compete-with-the-china-s-belt-and-road

Sun, Y. (2014). China’s Aid to Africa: Monster or Messiah? Brookings. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/articles/chinas-aid-to-africa-monster-or-messiah/

The State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China. (2023). The Belt and Road Initiative: A Key Pillar of the Global Community of Shared Future. Retrieved from https://english.www.gov.cn/archive/whitepaper/202310/10/content_WS6524b55fc6d0868f4e8e014c.html

Tokede, K. (2023). Cost of Sales, FX Shrinks Julius Berger’s Profit. ThisDay. Retrieved from https://www.thisdaylive.com/index.php/2023/11/20/cost-of-sales-fx-shrinks-julius-bergers-profit

UNESCAP-World Bank. (2023). Trade Cost Database. Retrieved from https://www.unescap.org/resources/escap-world-bank-trade-cost-database

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. (2017). Economic Development in Africa: Debt Dynamics and Development Finance in Africa. Retrieved from https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/aldcafrica2016_en.pdf?__cf_chl_tk=pBjk6Z9U5nq56_ngbqtPZMOMN17m.46MwhqKly.XZ4E-1711786009-0.0.1.1-1599

United Nations Economic Commission for Africa. (2022). Implications of the African Continental Free Trade Area for Demand for Transport Infrastructure and Services: Summary Report. Africa Business Forum 2022. Retrieved from https://archive.uneca.org/sites/default/files/uploaded-documents/abf/abf2022/eng-summary_of_ecas_report_on_implications_of_afcfta_on_transport_services_.pdf

World Bank. (2023). Unlocking the Development Potential of Public Debt in Sub-Saharan Africa. Retrieved from https://www.worldbank.org/en/results/2023/12/15/unlocking-the-development-potential-of-public-debt-in-sub-saharan-africa

World Bank. (2022). Private Participation in Infrastructure (PPI): 2022 Annual Report. Retrieved from: https://ppi.worldbank.org/content/dam/PPI/documents/PPI_2022_Annual_Report.pdf

Xinhua. (2019). Private sector seeks pragmatic cooperation under BRI. Retrieved from http://english.scio.gov.cn/BRF2019/2019-04/26/content_74724875.htm#

Zelikow, D. & Savas, S. (2022). Mind the gap: Time to rethink infrastructure finance. World Bank Blogs. Retrieved from https://blogs.worldbank.org/ppps/mind-gap-time-rethink-infrastructure-finance

About the author

Teniola T. Tayo

Teniola Tayo is a Policy Advisor with a focus on regional integration issues in Africa including the African Continental Free Trade Area and wider trade, security and development policies on the continent.

Appendix 1

Models for public-private partnerships in infrastructure development (will need to be reproduced by designer)

1 Read more: https://au.int/en/ie/pida

2 The AFC has been instrumental in mobilising private capital for infrastructure projects across Africa and this is just one of several ongoing efforts.

3 Read more: https://lekkiport.com/project-overview-structure/

4 This was shared as the volume of commitments by Ursula von der Leyen during the 2023 Global Gateway Forum: https://audiovisual.ec.europa.eu/en/video/I-248442