Summary

- Africa's industrialisation has been lagging for the past four decades. Despite marginal improvements in product export concentration and diversification indices, Africa's performance remains significantly lower than its peers and is largely focused on raw materials exports.

- South Africa is the most industrialised country on the continent, with Morocco, Egypt, Tunisia, Mauritius and Eswatini closely behind.

- The Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), and Southern African Development Community (SADC) regions, with their relatively high industrialisation indicators, stand as beacons of the potential for industrialisation in Africa, demonstrating the power of regional cooperation and the potential for significant growth.

- Drivers for the countries making good progress on industrialisation in Africa include strategic location, resource abundance, infrastructure development, skilled labour force, a strong financial system, political stability, regional leadership and aggressive pursuit of innovation and technology.

- Germany and the European Union (EU) have a crucial role in supporting African industrialisation. This can be achieved through increased funding and technical assistance, particularly in developing complementary technical and vocational skills training (TVET). In addition, inbound foreign direct investment (FDI) by European companies into renewables, component manufacturing and nascent industries such as green hydrogen can significantly boost African industrialisation. Lastly, supporting broader business environment reforms can create a more conducive environment for industrial growth.

Review of industrialisation in Africa

Since the Industrial Revolution, industrialisation has stood for the rapid transformation of the manufacturing sector compared to other economic sectors. It lies at the heart of structural change and the accompanying economic growth and development (World Bank, 2021). The empirical evidence shows that countries whose manufacturing sectors grow the fastest among all sectors can industrialise and boost their incomes (Guy-Diby & Renard, 2015). Several explanations exist for the linkages between industrialisation and economic growth. According to conventional structural change theory, industrialisation is commonly associated with redistributing capital and labour from low to high-productivity sectors, given the right technology (Rodrik, 2013). As labour and other resources shift from agriculture to advanced industries, employment and overall productivity rise. As a result, industrialisation has unparalleled connections to other sectors (Baldwin & Venables, 2015).

Industrialisation has always been an important aspiration for Africa, due in part to the existence of the continent’s young labour force, abundant natural resources and rapidly expanding domestic markets. Africa continues to be touted as the world’s ‘next industrial frontier’ (Mendes, 2022). Continental strategies such as the African Union Agenda 2063, the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the 2011 Action Plan for Accelerated Industrial Development emphasise that Africa’s industrial development will deliver inclusive growth, decent employment creation and numerous other development outcomes. Since 2000, continental Africa, especially sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), has witnessed rapid economic growth and poverty reduction through an ever-deeper integration into the global economy. However, most SSA countries continue to rely on commodity trading as their primary source of foreign exchange, exposing them to adverse international shocks, as evidenced by the global financial crisis (2007), the end of the commodity super cycle (2014/2015), the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russian-Ukraine war. A reliance on primary commodities exports is often a catalyst for corruption and rent-seeking behaviour, exacerbating the ‘paradox of plenty’, also known as the ‘resource curse’. Growth from such exports creates few new jobs in the domestic economy and therefore little improvement in living standards or human wellbeing.

Following independence, there was a brief period of industrial growth in Africa, driven mostly by state investment and promotion of import substitution policies. The early post-independence industrialisation policies aimed to position these new nation-states away from the exploitative colonial enterprise and were predicated on adding value to their primary commodities before exporting them. For example, under Ghana’s President Kwame Nkrumah (1959-1966), the Volta River Project developed the Akosombo dam to provide cheap and reliable electricity for a newly built smelter (Acheampong & Tyce, 2023). However, this initial growth was followed by a 25-year decline in the industrial sector, beginning in the early 1970s. Reasons for the decline include successive military coups, which constrained long-term economic policymaking, external trade shocks like the 1970s oil crises, commodity price decreases, and the IMF World Bank-imposed structural adjustment programmes (SAPs) of the mid-1980s, which largely failed to support import substitution (Acheampong & Menyeh, 2023; Mendes, Bertella & Teixeira, 2014). State-led industrialisation strategies also frequently resulted in instances of corruption and mismanagement (Lopes & te Velde, 2021).

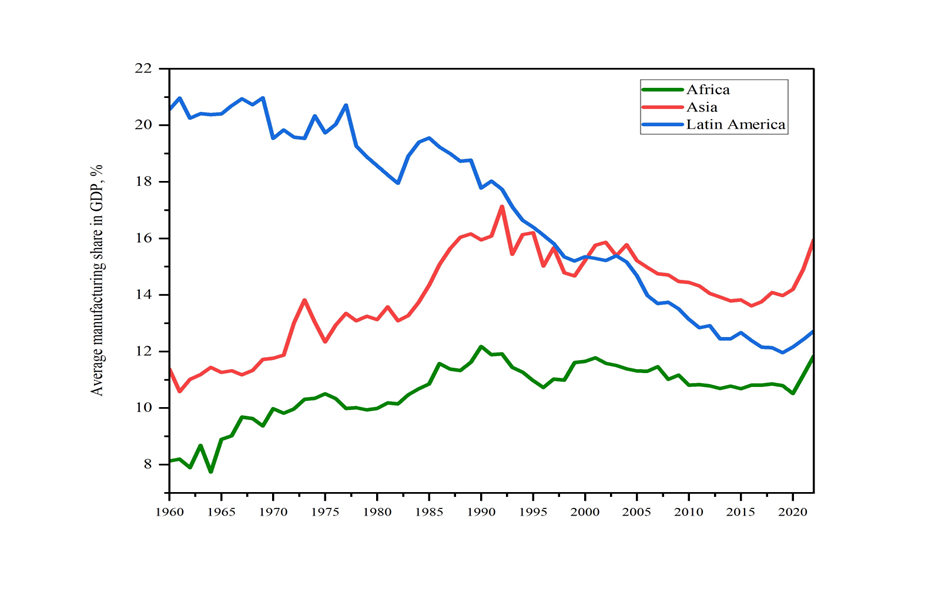

In many African countries, the manufacturing share of GDP – one of the indicators of industrialisation – has fallen since 1985, though it has recently picked up. On average, the continent has underperformed for the past four decades (10.57% manufacturing value added [MVA] as a percentage of GDP), trailing behind Asia (13.95%) and Latin America (16.93%). Evidence presented in Figure 1 suggests that despite an overall downward trend in manufacturing share in GDP for Asian and Latin American countries, Africa has been unable to keep pace with them. While Africa has almost 20% of the global population and land area, its contribution to economic output as measured by GDP is only about 3%; it has an even smaller share (2%) of world-MVA, most of which comes from relatively industrialised Northern Africa (UN, 2023).

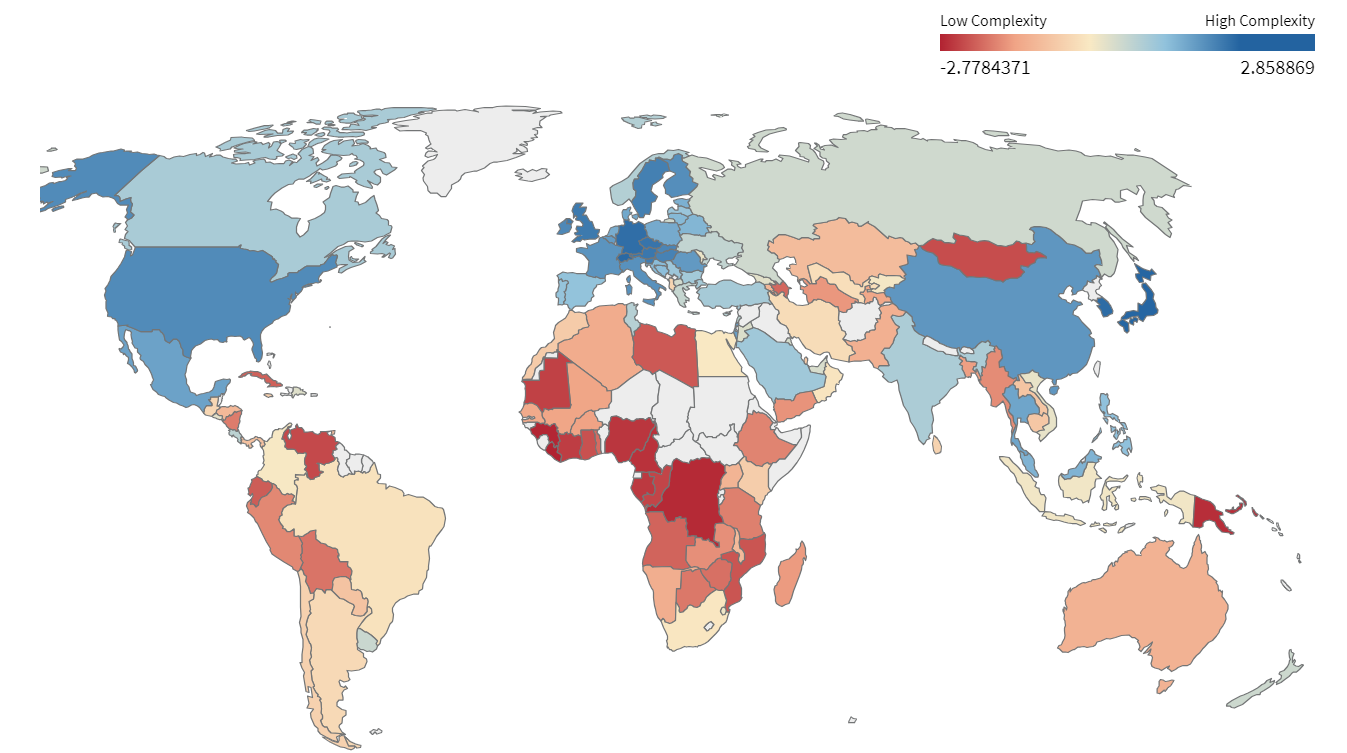

Africa has a less complex and less diversified portfolio of exports relative to other regions (Figure 2). For example, Africa has only marginally improved its product export concentration and diversification indices compared to East Asian or other developing economies. The diversification index, which measures the absolute deviation of the trade structure of a country from the world structure, takes values between 0 and 1, with a value closer to 1 indicating a more significant divergence from the global pattern. The concentration index also takes values between 0 and 1, with values closer to 1 indicating that a country's exports are highly concentrated on a few products (UNCTAD, 2022). In 2022, Africa had product export concentration and diversification indices of 0.593 and 0.240 versus 0.329 and 0.121 in East Asian economies.

Data source: World Development Indicators, The World Bank, 2023.

Source: Harvard Growth Lab, 2023

Moreover, unlike in Chile or India, even the move of labour from the agriculture sector has been towards lower-value service sectors rather than manufacturing (Yeboua, 2024). The evidence supports this, showing that labour in Africa has shifted from higher-productivity to lower-productivity employment since 1990 (Mensah, Owusu, Foster-McGregor & Szirmai (2023). The current pace of growth is unlikely to promote radical or fast structural change. If Africa is to become a player in the global market for manufactured goods and tradable services, it will have to improve industrial agglomeration and firm capabilities, and deploy other clever trade and industrial policies to its advantage.

Following the 2008-09 financial crises, African countries, with support from new trade partners such as China, sought to diversify the economy through the development of manufacturing, technology and services. The focus was on prioritising infrastructure development and fostering entrepreneurship and innovation. Despite obstacles such as inadequate infrastructure, limited financing, political instability and external disruptions like the COVID-19 pandemic, there is an increasing acknowledgement among African governments and development partners of the importance of sustainable and inclusive industrialisation for Africa’s long-term prosperity (Yeboua, 2024).

Who are the leading industrial countries in Africa?

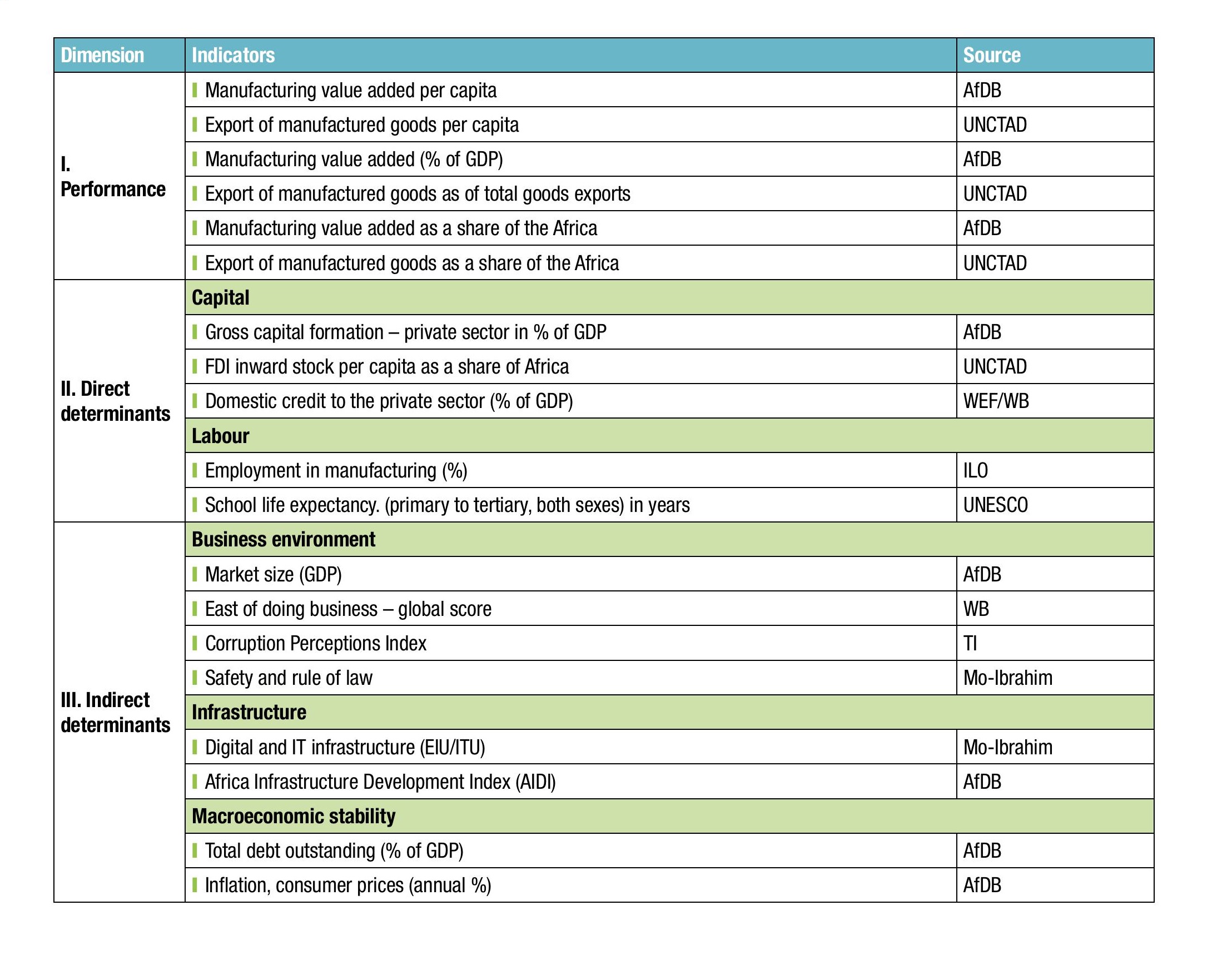

To answer this question, we use the inaugural Africa Industrialisation Index (AII) published by the African Development Bank (AfDB) in 2022. The AII is based on comprehensive, relevant and comparable data from multiple institutional providers. It comprises three sub-indices shown in Table 1. In sum, these are:

- Performance on manufacturing output and exports

- Direct determinants: direction of endowments (capital and labour) towards industrial development

- Indirect determinants: creating an enabling environment for industrialisation, including macroeconomic stability, sound institutions and infrastructure

Other comparative benchmarks or indicators that have been used in the past reports: (1) MVA added as a proportion of GDP and per capita; (2) the Global Competitiveness Index (GCI) by the World Economic Forum (WEF); (3) the World Competitiveness Scoreboard (WCS) by the Institute for Management Development (IMD); (4) the Doing Business Index (DBI) by the World Bank; and (5) the Competitive Industrial Performance index (CIP) by UNIDO. These all report similar outcomes. For example, the CIP index is similar to the AII, although the latter covers all African countries and has 19 indicators (versus CIP’S 8).

Source: AfDB, 2022: p.21

Country trends

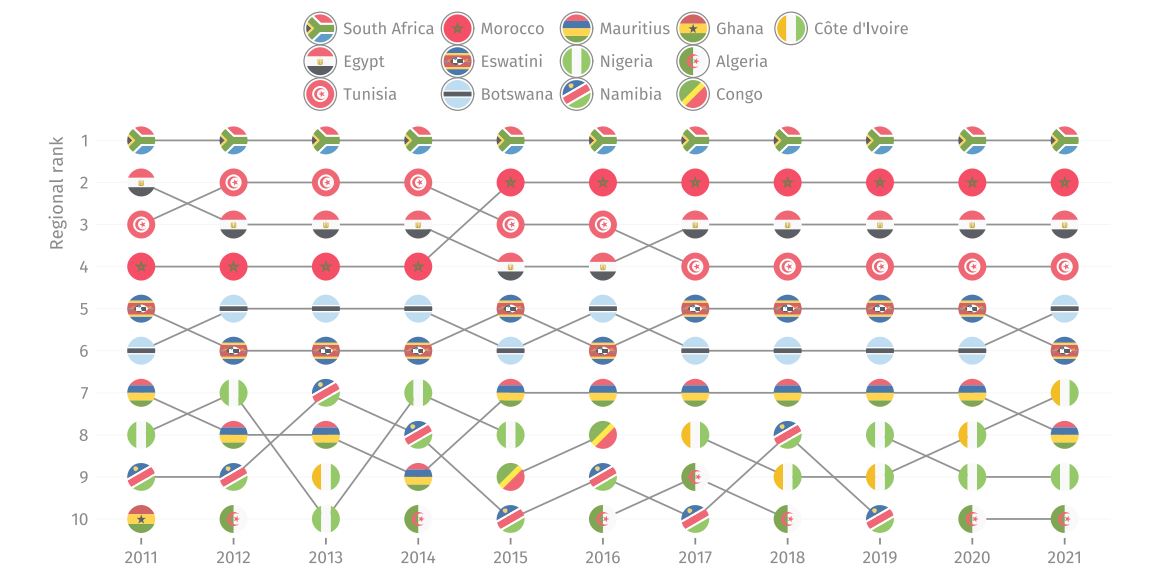

South Africa has maintained the dominant position in the AII and CIP indices for the past ten years, with Morocco, Egypt, Tunisia, Mauritius and Eswatini following closely behind (Table 2 and Figure 3). Northern and Southern African economies continue to focus on developing competitive industrial performance. Egypt, Morocco and Tunisia are among the top-ranked economies in the SDG 9 Industry index.

Nevertheless, there is some notable progress in countries like Côte d’Ivoire and Senegal, which climbed 11 positions between 2015 and 2020. Only eleven (11) African countries have more than 15% share of manufacturing in GDP in 2022, among them Algeria (34%), Eswatini (28%), Gabon (23%) and Zimbabwe (21%). Others include Congo DR (17%), Senegal (15%), Egypt (15%), and Morocco (15%) (World Bank, 2023).

Table 2 Africa’s leading industrialising countries

| Country | Resource Grouping | Income Grouping | 2011 | 2016 | 2021 | Quintile 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| South Africa | Other resource intensive | Middle-income | 0.8937 (1) | 0.8669 (1) | 0.8404 (1) | Top |

| Morocco | Oil exporters | Middle-income | 0.7996 (2) | 0.8201 (2) | 0.8327 (2) | |

| Egypt | Oil exporters | Middle-income | 0.7525 (4) | 0.7813 (4) | 0.7877 (3) | |

| Tunisia | Non-resource intensive | Middle-income | 0.7991 (3) | 0.7914 (3) | 0.7714 (4) | |

| Mauritius | Non-resource intensive | Middle-income | 0.6909 (5) | 0.7061 (5) | 0.6685 (5) | |

| Eswatini | Non-resource intensive | Middle-income | 0.6439 (6) | 0.6247 (7) | 0.6423 (6) | |

| Senegal | Non-resource intensive | Middle-income | 0.5772 (11) | 0.5880 (11) | 0.6147 (7) | |

| Nigeria | Oil exporters | Middle-income | 0.5792 (10) | 0.5635 (17) | 0.6046 (8) | |

| Kenya | Non-resource intensive | Middle-income | 0.5837 (9) | 0.5983 (10) | 0.6029 (9) | |

| Namibia | Other resource intensive | Middle-income | 0.6133 (7) | 0.6009 (8) | 0.6014 (10) | |

| Algeria | Oil exporters | Middle-income | 0.5678 (12) | 0.6001 (9) | 0.5978 (11) | Upper-middle |

| Gabon | Oil exporters | Middle-income | 0.5379 (19) | 0.5822 (13) | 0.5834 (12) | |

| Côte d'Ivoire | Non-resource intensive | Middle-income | 0.5321 (21) | 0.5776 (14) | 0.5830 (13) | |

| Ghana | Other resource intensive | Middle-income | 0.5495 (16) | 0.5850 (12) | 0.5799 (14) | |

| Equatorial Guinea | Oil exporters | Middle-income | 0.6124 (8) | 0.5645 (16) | 0.5666 (15) | |

| Congo DR | Other resource intensive | Low-income | 0.4797 (30) | 0.5387 (23) | 0.5646 (16) | |

| Botswana | Other resource intensive | Middle-income | 0.5524 (14) | 0.5672 (15) | 0.5587 (17) | |

| Benin | Non-resource intensive | Middle-income | 0.4777 (31) | 0.4942 (33) | 0.5497 (18) | |

| Zambia | Other resource intensive | Middle-income | 0.5343 (20) | 0.5527 (18) | 0.5423 (19) | |

| Uganda | Non-resource intensive | Low-income | 0.5293 (22) | 0.5506 (19) | 0.5418 (20) | |

| Tanzania | Other resource intensive | Low-income | 0.5073 (26) | 0.5190 (26) | 0.5389 (21) | |

| Lesotho | Non-resource intensive | Middle-income | 0.5382 (18) | 0.5495 (20) | 0.5372 (22) | Middle |

| Congo | Oil exporters | Middle-income | 0.5645 (13) | 0.6512 (6) | 0.5322 (23) | |

| Cameroon | Oil exporters | Middle-income | 0.5522 (15) | 0.5419 (21) | 0.5300 (24) | |

| Ethiopia | Non-resource intensive | Low-income | 0.4582 (36) | 0.5134 (28) | 0.5242 (25) | |

| Togo | Non-resource intensive | Low-income | 0.4940 (28) | 0.5300 (25) | 0.5191 (26) | |

| Seychelles | Non-resource intensive | Middle-income | 0.5490 (17) | 0.5178 (27) | 0.5097 (27) | |

| Madagascar | Non-resource intensive | Low-income | 0.4887 (29) | 0.5075 (31) | 0.5040 (28) | |

| Libya | Oil exporters | Middle-income | 0.5216 (23) | 0.5021 (32) | 0.5036 (29) | |

| Mozambique | Non-resource intensive | Low-income | 0.4614 (35) | 0.5115 (30) | 0.5027 (30) | |

| Cabo Verde | Non-resource intensive | Middle-income | 0.5176 (24) | 0.5331 (24) | 0.5007 (31) | |

| Zimbabwe | Other resource intensive | Low-income | 0.5044 (27) | 0.5120 (29) | 0.4974 (32) | Lower-middle |

| Djibouti | Non-resource intensive | Middle-income | 0.3869 (48) | 0.4701 (36) | 0.4936 (33) | |

| Angola | Oil exporters | Middle-income | 0.5158 (25) | 0.5391 (22) | 0.4865 (34) | |

| Rwanda | Non-resource intensive | Low-income | 0.4177 (41) | 0.4385 (41) | 0.4754 (35) | |

| Burkina Faso | Other resource intensive | Low-income | 0.4469 (38) | 0.4640 (37) | 0.4699 (36) | |

| Mauritania | Non-resource intensive | Middle-income | 0.4376 (40) | 0.4512 (39) | 0.4632 (37) | |

| Mali | Other resource intensive | Low-income | 0.4696 (32) | 0.4623 (38) | 0.4612 (38) | |

| Niger | Other resource intensive | Low-income | 0.4678 (33) | 0.4747 (35) | 0.4606 (39) | |

| Guinea | Other resource intensive | Middle-income | 0.3941 (47) | 0.4197 (44) | 0.4562 (40) | |

| Sudan | Oil exporters | Low-income | 0.4648 (34) | 0.4853 (34) | 0.4522 (41) | |

| Liberia | Other resource intensive | Low-income | 0.4413 (39) | 0.4448 (40) | 0.4409 (42) | Bottom |

| Malawi | Non-resource intensive | Low-income | 0.4552 (37) | 0.4380 (42) | 0.4229 (43) | |

| São Tomé & Príncipe | Non-resource intensive | Middle-income | 0.4165 (42) | 0.3997 (47) | 0.4198 (44) | |

| Chad | Oil exporters | Low-income | 0.4097 (43) | 0.4275 (43) | 0.4178 (45) | |

| Comoros | Non-resource intensive | Middle-income | 0.3968 (46) | 0.3933 (48) | 0.4078 (46) | |

| Eritrea | Non-resource intensive | Low-income | 0.4083 (44) | 0.4021 (46) | 0.4041 (47) | |

| Central African Republic | Other resource intensive | Low-income | 0.3863 (49) | 0.4071 (45) | 0.4018 (48) | |

| Sierra Leone | Other resource intensive | Low-income | 0.4012 (45) | 0.3771 (49) | 0.3777 (49) | |

| Guinea-Bissau | Non-resource intensive | Low-income | 0.3429 (51) | 0.3524 (51) | 0.3663 (50) | |

| Burundi | Non-resource intensive | Low-income | 0.3281 (52) | 0.3702 (50) | 0.3483 (51) | |

| Gambia | Non-resource intensive | Low-income | 0.3794 (50) | 0.3433 (52) | 0.3455 (52) |

Note: Figures in brackets are the countries’ ranks in the corresponding year.

Source: Adapted from AfDB, 2022

Source: UNIDO, 2023.

An expanding number of African nations have tried to promote industrialisation and diversify their economies in recent years. Ethiopia, renowned for its burgeoning leather industry, and Ghana and Kenya, both situated in the pharmaceutical sector, have promising emerging industries. Several countries are developing networks of special economic zones (SEZs) and industrial parks (MEZs) as part of their efforts to foster the expansion of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). These investments have yielded substantial returns. From 2010 to 2019, MVA in Ethiopia experienced a fourfold growth, reaching just below USD 5 billion (African Development Bank, 2022). Ethiopia’s textile and garment industry is experiencing rapid growth, with domestic and multinational firms producing textiles for domestic and global markets. The government launched Plan 2020 to generate USD 1 billion in export earnings and over 300,000 employment opportunities. Over the past six years, the textile and apparel industry expanded by an average of 51%, and foreign investors were granted licences for over 65 international textile investment projects. The textile industry’s expansion directly results from the government’s industrial development strategy (Alliance Experts, 2024).

In Rwanda, the government has set up technology hubs and incubators as part of a digitalisation strategy to boost economic growth and generate employment opportunities. With a projected GDP contribution of 3% in 2020, the ICT sector has made a substantial contribution to Rwanda’s economy. Thousands of people are employed throughout the supply chain, as well as in additional indirect jobs. Within ten years, the government hopes to triple the sector’s contribution to at least 10%. A thriving startup ecosystem has also been created in Rwanda due to the country’s growing entrepreneurial culture, which has encouraged many young people to launch their own ICT companies. The workforce’s increased skill, especially those with STEM degrees, has also helped transform the economy. In addition to promoting regional integration, Rwanda’s membership in the East African Community (EAC) has opened up new prospects for the ICT industry.

Ghana’s automotive industry is another nascent sector with great transformation and job creation potential. An estimated 100,000 vehicles are imported annually by the country, of which 90% are pre-owned or used (second-hand). To reduce reliance on pre-owned vehicles, in 2019 the government passed the Ghana Automotive Development Policy to attract investments from renowned Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs) to establish a fully integrated and competitive industrial hub for automotive assembly. Since then, over 11 OEMS have set up assembly plants in the country for the local market and sub-regional exports (The Business & Financial Times, 2023). These include Suzuki and Toyota (Toyota Tsusho Corporation), Volkswagen Group, Nissan (Nissan Motors Corporation) and Renault (Stallion Group). The entry of these OEMs bodes well for creating significant positive spillovers into local manufacturing and the metals sector in the medium to long term. However, these must be catalysed by deliberate policies to move from basic semi-knocked-down (SKDs) assembly to fully-built units (FBUs) where vehicles are largely manufactured, assembled and completed at an in-country production facility. The Ghanaian automobile market is anticipated to reach USD 2.07 billion by 2029 from USD 1.93 billion in 2024. Meanwhile, the government has devised a strategy to procure 1,000 electric buses for intercity (60%) and intracity (40%) transportation, in addition to charging and maintenance infrastructure. Ghana aspires to operate 12,027 electric public buses nationwide by 2050, accounting for 32% of the overall fleet.

Regional trends

Table 3 shows how the different economic regions compare on the various benchmarks. Overall, the COMESA, ECOWAS and SADC regions have the highest industrialisation indicators and, by extension, industrialisation potential.

Table 3: Economic regional analysis of the comparative benchmarks

| Region | MVA per capita 2022 (2015 US$) | MVA growth rate 2022 (%) | MVA share in GDP 2022 (%) | MHT share in MVA 2020 (%) | Industry value added share in GDP 2022 (%) | Manufacturing share in exports 2022 (%) | MHT share in manufacturing exports 2022 (%) | Manufacturing share in employment in 2021 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECOWAS | 195 | 2.6 | 10.3 | 28.8 | 15.9 | 16.9 | 20.4 | 8.5 |

| SADC | 197 | 2.9 | 10.4 | 18.1 | 20.8 | 42.0 | 32.2 | 5.3 |

| COMSEA | 182 | 5.3 | 11.0 | 19.4 | 21.8 | 43.6 | 31.1 | 7.0 |

| IGAD | 70 | 5.0 | 6.8 | 14.2 | 10.3 | 44.5 | 25.2 | 5.8 |

| EAC | 101 | 5.6 | 10.8 | 10.3 | 21.1 | 42.0 | 17.9 | 5.2 |

Note: MVA refers to manufacturing value added. MHT refers to the medium-high and high-tech industry. Source: UNIDO

ECOWAS

The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) has revised its Industrial Agenda (WACIP) to focus on four industries: agro-industries, textiles and garments, pharmaceuticals, and automobile and automotive components. The primary focus on these industries stems from their potential to drive sustainable industrialisation, employment generation, economic competitiveness and regional integration. The revised WACIP demonstrates ECOWAS’ willingness to adapt and integrate lessons learned, highlighting the iterative nature of regional industrialisation processes. However, given the large number of unemployed youth, questions have been raised about the appropriateness of regional-level industrial policy (ECDPM, 2016).

SADC/COMESA

Due to the region’s capital and technology-intensive hydrocarbon and mineral production, as well as its lack of forward and backward linkages with the rest of the economy, employment growth has been constrained. Nevertheless, the region is experiencing notable enhancements in its generation capacity due to the anticipated launch of major power generation projects in Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda and Zambia. Establishing the Zambia-Tanzania-Kenya and Ethiopia-Kenya interconnectors will enable the exchange of electricity between the southern and northern power grids. This is a potential enabler of rapid industrialisation. The Lobito Corridor, which connects the southern DRC and north-western Zambia to regional and global trade markets via the port of Lobito in Angola, is another potential industrialisation driver, especially for critical minerals value chains, including battery manufacturing (Acheampong, 2024).

IGAD

While Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) nations have experienced robust economic growth recently, detailed analysis shows that this growth has yet to result in significant structural transformation. Given the region’s 255 million inhabitants, of whom more than half are under 25 years old, unemployment is a significant issue. Primary commodities comprise the majority of IGAD member states’ exports and are susceptible to global price fluctuations. Due to the region’s weak manufacturing sector, it continues to grapple with substantial poverty and unemployment.

EAC

Industrialisation in the East African Community (EAC) is hampered by low electricity penetration, high costs, poor transport infrastructure, low human capital and protectionist policies.

What have been the reasons for African countries’ success in industrialisation?

Africa’s most industrialised nation, South Africa, has a varied economy and highly developed industrial sectors. Its strategic location at the southern tip of Africa, wealth of natural resources, infrastructure development, skilled labour force, strong financial system, political stability, economic diversification, regional leadership, and dedication to innovation and technology are important factors in its success. South Africa also has well-established vocational training programmes and education systems, while the nation's robust financial system encourages entrepreneurship and makes investments in industrial projects easier. Furthermore, due to its advantageous geographical location, South Africa is able to access both domestic and global markets, which attracts foreign direct investment (FDI). Consequently, the nation contributes significantly to regional cooperation and economic integration.

The small Southern African nation of Eswatini has also made strides in certain industrial sectors (e.g. its robust textile and apparel industry), taking advantage of its strategic location, investment incentives, political stability, trade agreements, skills development, infrastructure development and diversification initiatives (World Bank, 2022). The government provides tax incentives, logistical backing and efficient regulatory systems to incentivise foreign direct investment. Political stability reduces the risks associated with conducting business in the nation and inspires investor confidence. Furthermore, Eswatini has undertaken infrastructure initiatives to foster economic diversification beyond conventional sectors such as agriculture. Industrial development policies have been enacted by the government, fostering an environment conducive to the flourishing of businesses and their contribution to the expansion of the economy.

Gabon has also achieved notable progress in industrialisation owing to its vast natural resource reserves, most notably timber, manganese and oil (Arise, n.d.). Foreign investment and employment opportunities are generated by the oil industry, which is a pillar of the Gabonese economy. To support industrial activities, the nation has invested in infrastructure projects encompassing energy infrastructure, transport networks and telecommunications. Additionally, in an effort to develop other sectors, including mining, forestry, agriculture and manufacturing, Gabon is implementing diversification strategies. Political stability has also played a role in the nation’s achievements. The government encourages foreign investment by providing tax breaks and customs exemptions, among other measures (U.S. Department of State, 2023). In addition to investing in education and skill-development initiatives, Gabon has a qualified labour force. The nation has also fostered strategic alliances with foreign governments and international organisations to further industrial development.

Algeria, situated in North Africa, has emerged as a significant participant in industrial development owing to its formidable oil and gas sector, ample natural resources and diversified economic foundation (World Bank, 2024). Investments have been made in infrastructure projects, including water supply systems, transportation, energy and telecommunications, to support industrial activities and economic expansion. A skilled, knowledgeable, educated labour force contributes to the country’s success. To encourage investment, the government provides a range of incentives, such as preferential treatment, tax breaks, subsidies and access to land and infrastructure (BMZ, 2024). Benefitting from political stability, Algeria has established trade relations with regional and international partners and takes advantage of a strategic location in North Africa that grants access to regional and global markets. In an effort to foster industrialisation, bolster domestic industries and increase competitiveness, the Algerian government has enacted industrial policies. Nonetheless, socioeconomic disparities, bureaucratic obstacles, regulatory restrictions and infrastructure deficiencies persist.

Egypt is a leading industrialised nation in Africa, with a robust manufacturing sector and a diverse industrial base (U.S. Department of State, 2023). Due to its advantageous geographical position at the intersection of Africa, the Middle East and Europe, the country attracts foreign investment and trade. Egypt’s expansive domestic market presents industrial producers with prospects to expand their production capacities. Infrastructure investment, encompassing energy and transportation, facilitates industrial operations and encourages investment. Diverse manufacturing substantially contributes to the gross domestic product and employment. Egypt has ratified multiple free trade agreements, which have promoted export-oriented industrialisation and facilitated trade integration. Its proficient labour force, governmental backing, technological advancements and innovation, tourism and services sector, political stability, and reform initiatives contribute to its success. Egypt’s ongoing endeavours to confront obstacles and exploit prospects have the potential to propel industrial expansion and economic progress even further.

What are the learnings for other African countries?

Policymakers should contemplate implementing structuralist industrial policies that prioritise the development of labour-intensive and knowledge-intensive sectors. Such policy directions are outlined below:

- Improved regional infrastructure, particularly transport, energy and communications, would attract increased investment in industry across the continent.

- Special Economic Zones with incentives and reliable energy and ICT infrastructure would also encourage private sector investment. However, public sector investments in infrastructure and human capital development are needed to attract private sector-led industrialisation.

- Despite recent sovereign debt issues in several African countries, there is still a significant demand for infrastructure and human capital development. Concessional financing for infrastructure is needed to reduce economic harm from rising debt burdens. Political coordination and the erosion of protectionist policies could attract more inward financing.

- Processing and beneficiation of mineral resources in-country, especially green minerals like nickel, lithium and cobalt. This will create green industrialisation opportunities for endowed countries, new avenues for green growth and sustainable job creation. Several African countries including Zimbabwe, Uganda, Tanzania, Namibia and Botswana, are considering this option to mitigate the energy deficit through green energy and industrialisation solutions, e.g. solar energy, e-batteries and wind energy turbines. This will further minimise GHG emissions, wean agriculture production from its weather dependency though green energy-powered irrigation innovations, expand the reach of electricity access, which is currently very low in Africa compared to other developing regions, and help to boost manufacturing value added to GDP.

By investing in education and infrastructure development, diversifying their economies, promoting good governance and political stability, encouraging innovation and entrepreneurship, fostering regional integration, and advancing sustainable development, the least industrialised African countries can gain insights from leading industrialised nations. The aforementioned insights may be implemented in African nations with the intention of formulating context-specific strategies that promote sustainable industrialisation and economic well-being. The least industrialised African nations can foster a culture of entrepreneurship, promote good governance, invest in education and infrastructure, diversify their economies and develop strategies that contribute to their economic growth and prosperity.

What role can Germany and the European Union (EU) play in this?

Germany and the EU can support African countries to industrialise faster through deepening the provision of funding and technical assistance. This can be done by helping to develop complementary technical and vocational skills training (TVET), as done so by the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ); encouraging inbound FDI by European companies into renewables, component manufacturing and nascent industries such as green hydrogen; and supporting broader regulatory and business environment reforms. For example, through the GIZ the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) has been supporting the Ghana Skills Development Initiative which seeks to support the Ghanaian Government’s strategy to improve TVET systems to better meet the requirements for sustainable development (GIZ, 2023). One of the major areas of focus has been ensuring the availability of vocational schools offering training courses in the green sector. Such education and capacity building support initiatives can be expanded and rolled out to other countries on the continent to ensure that skilled mid-level manpower is developed with the capacity for industrial management, technology and innovation.

Additionally, the EU should expand its technical assistance provision to cover regional institutions involved in policymaking and regulatory frameworks that support industrial growth. In the context of increasing intra-African trade, such assistance can help African countries implement reforms that create favourable business environments via special economic zones, trade facilitation and proactive industrial policies.

As mentioned above, European companies should invest in African renewable energy and component manufacturing as well as nascent industries such as green hydrogen, as is already happening in Namibia. Meeting the 1.5°C target of the Paris Agreement calls for rapid decarbonisation, which means drastically reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from all sources. The opportunities for cooperation in this context are significant: While EU-Africa relations are steeped in colonial history, relations have evolved in recent years, underpinned by the 2007 Joint Africa-EU Strategy and the Joint Vision 2030. The Global Gateway, which is one of the pillars of the Joint Vision 2023, focuses on sustainable investments in infrastructure – digital, energy and transport, among others (European Commission, 2024). Within the green space, the emphasis is on sustainable energy, biodiversity, agri-food systems, climate resilience and disaster risk reduction. The EU must walk the talk to fulfil its pledge to help mobilise EUR 150 billion in public and private investments by 2027 for Africa (European Commission, 2021).

Lastly, the EU must advocate for rechannelling the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF’s) Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) into financing climate action in Africa. While Africa’s contribution to global GHGs remains under 4%, the continent is among the most vulnerable to the impact of extreme weather events. Compounding this is the fact that many countries in the region face persistent debt-sustainability challenges, limiting their ability to finance the investments needed to address climate change. Under the Paris Agreement, Africa needs USD 2.8 trillion by 2030 (USD 280 billion annually) to implement its nationally determined contributions. This is almost equivalent to the continent’s entire GDP of USD 3 trillion in 2022 (Climate Policy Initiative, 2022; Statista, 2024). Actual climate finance flows to Africa amounted to just USD 30 billion in 2020, a mere 11% of the annual target and 3% of global climate finance (Adesina, 2023). Rechannelling of these new funds through multilateral development banks such as the African Development Bank (AfDB) would finance climate action and new green industries. These funds would catalyse renewable energy and climate-resilient investments across the continent.

References

Acheampong, T., & Menyeh, B. (2023). The energy transition, critical minerals and industrialisation in Sub-Saharan Africa. In Mining law and governance in Africa (1st ed.). http://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9781003284437-3

Acheampong, T., & Tyce, M. (2024). Navigating the energy transition and industrial decarbonisation: Ghana’s latest bid to develop an integrated bauxite-to-aluminium industry. Energy Research & Social Science, 107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2023.103337

Adesina, A. (2023). Mobilising private sector financing for climate and green growth in Africa. https://newafricanmagazine.com/29682/

African Development Bank. (2022). Africa industrialisation index 2022. https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/africa-industrialization-index-2022

Alliance Experts. (2024). The textile industry in Ethiopia and Ethiopian garment production. https://www.allianceexperts.com/trends-in-the-textile-industry-in-ethiopia/

Arise. (n.d.). Major industries in Gabon. https://www.ariseiip.com/major-industries-in-gabon/

Baldwin, R., & Venables, A. (2015). Trade policy and industrialisation when backward and forward linkages matter. Research in Economics, 69(2), 123-131.

BMZ. (2024). Algeria: Cooperation for ‘green’ growth, renewable energy and decent jobs. https://www.bmz.de/en/countries/algeria

Climate Policy Initiative. (2022). Landscape of climate finance in Africa. https://www.climatepolicyinitiative.org/publication/landscape-of-climate-finance-in-africa/

ECDPM. (2016). The political economy of regional organisations in Africa - PEDRO project (2018-2020). https://ecdpm.org/work/political-economy-regional-organisations-africa-pedro-project

European Commission. (2024). Global gateway. https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/stronger-europe-world/global-gateway_en

European Commission. (2021). Global gateway: Up to €300 billion for the European Union’s strategy to boost sustainable links around the world. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_21_6433

GIZ. (2023). Developing Ghana’s TVET system. https://www.giz.de/en/worldwide/121132.html

Guy-Diby, S., & Renard, M. (2015). Foreign direct investment inflows and the industrialization of African countries. World Development, 74, 43-57.

Industrial Analytics Platform. (2021). SDG-9 industry index. https://iap.unido.org/data/sdg-9-industry?p=BDI

International Institute for Management Development. (2024). World competitiveness ranking. https://www.imd.org/centers/wcc/world-competitiveness-center/rankings/world-competitiveness-ranking/

Lopes, C., & te Velde, D. (2021). Structural transformation, economic development, and industrialisation in Africa post-Covid-19. Africa Paper Series 1.

Mendes, A., Bertella, M., & Teixeira, R. (2014). Industrialisation in Sub-Saharan Africa and import substitution policy. Revista Brasileira de Política Internacional, 57(1), 80-104. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0101-31572014000100008

Mendes, L. (2022). ‘Africa is the future’: All eyes turn to the youngest continent as the next frontier for growth. https://www.tradefinanceglobal.com/posts/africa-is-the-future-all-eyes-turn-to-youngest-continent-as-next-frontier-for-growth/

Mensah, E., Owusu, S., Foster-McGregor, N., & Szirmai, A. (2023). Structural change, productivity growth and labour market turbulence in Sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of African Economies, 32(3), 175-208.

Rodrik, D. (2013). Structural change, fundamentals, and growth: An overview. Institute for Advanced Study.

Statista. (2024). Gross domestic product (GDP) in Africa from 2010 to 2027. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1300858/total-gdp-value-in-africa/

The Business & Financial Times. (2023). Auto dev’t policy spurs industry’s growth. https://thebftonline.com/2023/06/30/auto-devt-policy-spurs-industrys-growth/

UNCTAD. (2022). Data center statistical portal. https://unctadstat.unctad.org/datacentre/

UNIDO. (n.d.). Composite measure of industrial performance for cross-country analysis. https://unstats.un.org/unsd/ccsa/isi/2013/Paper-UNIDO.pdf

United Nations. (2023). Factsheet: Africa. https://www.unido.org/sites/default/files/unido-publications/2023-12/documents_Yearbook_2023_UNIDO_IndustrialStatistics_Yearbook_2023_Africa.pdf

U.S. Department of State. (2023). 2023 investment climate statements: Gabon. https://www.state.gov/reports/2023-investment-climate-statements/gabon/

U.S. Department of State. (2023). 2023 investment climate statements: Egypt. https://www.state.gov/reports/2023-investment-climate-statements/egypt/

World Bank. (2021). Industrialization in Sub-Saharan Africa: Seizing opportunities in global value chains. https://www.worldbank.org/en/region/afr/publication/industrialization-in-subsaharan-africa-seizing

World Bank. (2024). Overview: Gabon. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/gabon/overview

World Bank. (2024). Overview: Algeria. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/algeria/overview

World Bank. (2023). Manufacturing, value added (% of GDP) - Sub-Saharan Africa. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NV.IND.MANF.ZS?locations=ZG&most_recent_value_desc=tru&view=map

World Bank. (2022). Country private sector diagnostic: Creating markets in Eswatini. https://www.ifc.org/content/dam/ifc/doc/mgrt/cpsd-eswatini.pdf

World Economic Forum. (2020). Global competitiveness report special edition 2020: How countries are performing on the road to recovery. https://www.weforum.org/publications/the-global-competitiveness-report-2020/

Yeboua, K. (2024). Manufacturing. https://futures.issafrica.org/thematic/07-manufacturing

About the Authors

Theo Acheampong, PhD

Dr Theo Acheampong is an economist and political risk expert with over 15 years of experience in academia, public financial management, the extractives industry, and private sector development in frontier emerging markets.

Prince Asare Vitenu-Sackey

Prince Asare Vitenu-Sackey is a PhD student at the University of Strathclyde with research interests in environmental, monetary, and development economics. With over 20 published articles, his work explores the intricate relationship between the environment and macroeconomic policies.