“Nothing is impossible” is inscribed on a plaque on the large desk in the expansive office. As we approach the desk, Aliko Dangote seated behind it, motions to me to sit. He is on the phone talking numbers and scribbling on a notepad. Another curious item on the desk is an ordinary calculator, the type commonly used by vendors in market stalls. Dangote punches on the calculator buttons, speaks some more, scribbles on his notepad and works the calculator again. Dangote concludes his phone call less than five minutes later. We exchange pleasantries, and thus begins my nearly two-hour long discussion with Africa’s and the world’s richest black man, Aliko Dangote, on his experience of building a Nigerian industrial conglomerate, on government policy and the business environment, and on his vision for the future.

Dangote’s journey to becoming an industrial magnate closely mirrors the transition of Nigeria’s non-oil economy to what it is today and what it could be in the future. It is no secret that Dangote comes from an affluent and aristocratic family in Kano in northern Nigeria. He is the great-grandson of the wealthy commodity trader Alhassan Dantata who, during his time in the early 1900s, was West Africa’s richest man. With a N500,000 loan from an uncle, Dangote set up a bulk commodity trading group in 1978 to take advantage of the liberalization of commodity imports. Through his family wealth, social networks, and government connections, the Dangote Group secured import licenses like several other business-minded Nigerians, to trade and process food including pasta, flour, sugar, and beverages throughout the 1980s up to the mid-1990s.

From the late 1990s, however, Dangote began a decisive paradigm shift, from trading to manufacturing for import substitution and backward integration. On a business trip to Brazil, as he explained to me, he visited a factory which employed about 4,600 people. He was fascinated by “ . . . the number of people walking into the factory to work, and walking out after work, and how all those people depended on the owners of the factory, and their families, and how they organised themselves.”[1] He realized how manufacturing adds value to society in a more holistic manner than trading—various products are made from a raw material, buildings are erected, workers are employed, local demand is met, there is backward integration with the rest of the economy and the whole of society benefits. At the time, he continues, Brazil was experiencing “hyper-inflation . . . the currency was devaluing almost every minute . . . worse issues than us in Nigeria.” So Dangote wondered why Nigeria “ . . . couldn’t progress with industrialization” despite not having Brazil’s severe macroeconomic challenges. It was this epiphany in Brazil that motivated Aliko Dangote to venture into manufacturing the same products he had for decades been importing to sell in Nigeria. Unstated, perhaps, is the realization of the profits to be made from manufacturing consumer goods.

Dangote’s business reorientation also coincided with a stabilizing policy environment that departed from the haphazardness of military rule in the 1980s and 1990s. The Nigerian government under Obasanjo was keen to liberalize the economy, attract private investment, and encourage domestic entrepreneurs. In banking and finance, as well as ICT, as we shall examine, economic reforms attracted domestic investors who acquired licenses to set up telecoms companies, banks, pension administrators, and other financial firms in ways that fundamentally transformed and modernized these industries. In sub-sectors of agriculture and manufacturing, the policy direction was less consistent, taking the form of substituting imports with domestic produce and manufactures to build national self-sufficiency. For instance, in 2002, Obasanjo’s government hiked tariffs and banned imports of African print fabrics, biscuits, fruit juice, pasta, certain pharmaceuticals, sugar, and frozen poultry among others that had domestic substitutes.[2] The objective was clear: to help develop domestic production capacity and protect Nigerians from substandard imports. Yet, the beneficiaries of these import bans also happened to be highly connected business elites, including Obasanjo himself who owned Ota Farms, a livestock farm producing at scale, which benefited directly from a ban on frozen meat imports. Another major beneficiary of this import substitution was the Dangote Group which was already processing flour, pasta, rice, salt, sugar, and other food staples.

Although Aliko Dangote was a household name in Nigeria by the late 1990s, it was really his foray into cement manufacturing that made his empire the transnational colossus it is today. During the privatization program of the early 2000s, he acquired state-owned cement companies, Benue Cement Company in 2000 and Obajana Cement Plc in 2002, as well as other government enterprises such as Savannah Sugar. In the background, the government also had restricted cement imports. In 2007, the Dangote Group commissioned the Obajana Cement plant with two production lines and capacity of 5 million tonnes per annum, making it the largest plant in sub-Saharan Africa. As Dangote explained to me, it cost over $1 billion of which $472 million was borrowed from various lenders including thirteen of Nigeria’s recently recapitalized banks and the International Finance Corporation (IFC). When a list of high-profile debtors was released by the Central Bank of Nigeria in 2009, as part of efforts to clean up nonperforming loans, Dangote’s companies featured as some of Nigeria’s top borrowers.[3]

Obajana began operations in 2006. From then onwards, Dangote’s rise was meteoric. In 2008, he was Nigeria’s richest man according to Forbes magazine. The company also began to expand operations abroad to Ghana, South Africa, and Zambia by 2012. Nigeria is now able to meet its domestic demand for cement due, in large part, to Dangote Cement, which supplies 12Mt of cement, representing a 65% share of the Nigerian market. Other important players in the cement industry include local firm Bua and the French company Lafarge. In June 2020, Dangote began to export bulk cement across West Africa from an export terminal he had built, thereby earning foreign exchange for Nigeria.

Today, the Dangote Group has a presence in seventeen African countries and is a market leader in cement on the continent. The conglomerate is a diversified portfolio of cement manufacturing, sugar milling, sugar refining, port operations, packaging material production, and salt refining, with an annual turnover of $4 billion. The Group is currently constructing Africa’s largest petroleum refinery, petrochemical plant, and fertilizer complex.[4] In September 2021, Aliko Dangote’s net worth was $12.4 billion as estimated by Forbes, crashing from a peak of $25 billion in March 2014 due in part to the collapse of the Nigerian naira.[5] He still retains the title of Africa’s richest man, and the world’s richest black man, which he earned in 2011 when he edged out Ethiopian-Saudi billionaire Mohammed al-Amoudi and America’s Oprah Winfrey.

While Aliko Dangote is largely celebrated in Nigeria and beyond, there are those who see him as representing an economy rigged in favor of the highly connected. Various government policies including tax waivers and import restrictions disproportionately benefit Dangote and other large-scale entrepreneurs to the detriment of foreign competitors and smaller enterprises. His deep social networks allow him extensive influence on policy individually, and as an important member of industry groups such as “Corporate Nigeria” and MAN, that some describe as policy capture. Thus, a combination of favorable policies, political influence, and Aliko Dangote’s own evident business acumen[6] as first mover in some industries has yielded impressive returns for his conglomerate. In some industries, Dangote is seen to have leveraged his scale of operations into monopoly power to choke foreign competitors and smaller-scale domestic entrepreneurs, according to a leaked U.S. government memo.[7]

In response to these criticisms, Dangote implies that as a first mover in the industries he operates within Nigeria’s tough business environment, he personally provides public services which then become public goods. As he explained to me, “in all Dangote factories we generate our own power and we’re not relying on the national grid at all, we’re not even connected to them.” They also build their own road networks and housing estates for workers; more recently building export terminals at Nigeria’s seaports in Lagos and Port Harcourt. In building the Obajana Cement Plant in Kogi in north-central Nigeria, he said:

"we ended up building a gas pipeline – 92km – to supply gas for the generators . . . for electricity. The place was a no man’s land – no housing to rent, the closest place was Lokoja, 38km. So we had to build about 472 houses. The water table was terrible . . . so all the boreholes we built collapsed . . . we had to build a dam; you can see the dam over there [he points to blow up photo on his wall].”

With all these unforeseen expenses, “the Obajana factory cost us about $1 billion, up from the initial $490 million.”

The private provision of these services generates positive externalities becoming public goods used by host communities. As he explained:

". . . wherever we land to do a business, the government will just run away, and they leave us with the community. We are the ones to make sure that they go to school . . . right now we have a place in Ogun state (Igbesu), we have issued road projects worth over N6 billion – we are doing the roads. Even now after doing the roads, the community [we are] repairing their schools, we have given them N250 million to do projects that they badly need.”

Other benefits to society including being the largest employer of labor beside the government, adding value in manufacturing, generating foreign exchange through exports in exchange for the tax waivers and other policies that allow the Dangote Group to break even, turn a profit, and open up that industry to other players. Interestingly, similar arguments are put forward by Nigeria’s international oil companies which provide some public services—including roads, schools, and hospitals in their host communities in the Niger Delta—although their impact on jobs creation and value addition is negligible.

The activities of Dangote and other large-scale entrepreneurs contributed to the growth of non-oil sectors of the Nigerian economy since the turn of the century. The expansion of food and beverage production, cement manufacturing, banking and finance, and ICT resulted from a combination of privileged political access and favorable policies for powerful entrepreneurs with demonstrable business acumen. Indeed, the future transformation of Nigeria’s other non-oil industries especially agriculture, manufacturing, and tech, may very well follow a similar trajectory of cement, telecoms, and finance. Therefore, a good understanding of what it would take to diversify Nigeria’s economy towards a post-oil future in the twenty-first century may lie in taking stock of recent experience. In this stocktaking, we unpack the combination of deliberate government policies, privileged political access, and entrepreneurial acumen.

The following examines how deliberate policy choices were made for crucial sector reforms within Nigeria’s post-military political settlement. We discuss how external constraints of volatile oil prices and the resulting fiscal pressures pushed Nigeria’s policymakers to liberalize the telecoms sector quickly and successfully. Yet, at this critical juncture, efforts to reform the downstream oil sector by boosting domestic fuel refining, removing subsidies, and investing in public services stalled. The fiscal pressures from global oil prices were insufficient to embolden successive governments to deregulate a downstream sector characterized by fuel imports to meet domestic demand and an expensive fossil fuel subsidy regime that consumes more government revenues than social expenditure that is popular among ordinary Nigerians. Instead, wider redistribution concerns for cheap fuel used in private generators due to insufficient grid electricity and in passenger vehicles due to sufficient mass transit disincentivized downstream oil sector reforms.

The Liberalization of the Telecoms Sector is driven by Domestic Capital

One sector where liberalization was successfully pursued is telecommunications, a major growth driver in the first decade of Nigeria’s democratization. The reforms succeeded due to a combination of external fiscal pressures on Nigeria’s ruling elites, the privileged allocation of rents in the form of mobile licenses to connected business elites and their entrepreneurial savvy in the productive use of these mobile licenses to build a telecoms industry that was founded on domestic investments and foreign technology. Let us take a closer look, then, at the sector’s underlying problems, the constraints and catalysts for reform, the actual policies undertaken, the key actors involved, and the outcomes.

By 1999, when Nigeria transitioned to democratic rule, the telecommunications sector was in dire straits. The sector was largely state-run with the public enterprise, the Nigeria Telecommunications Limited (NITEL) at its core. The notorious inefficiency of NITEL prompted the government to pencil the utility alongside 140 other SOEs for privatization during structural adjustment between 1988 and 1993. [8] The Nigerian Communications Commission (NCC) was set up as a regulator in 1992, while General Abdulsalam Abubakar’s military government promulgated the Public Enterprises Act of April 1999. Unlike, say, banking and finance, the government was not able to attract sufficient private investments in telecoms during structural adjustment. By the mid-1990s, any hope of attracting foreign investments vanished as Nigeria became an international pariah during General Abacha’s rule and multinationals outside the oil sector were wary of getting involved with the country. Towards the late 1990s, Nigeria still pressed on with efforts to attract private investments, especially in the new technology around cellular networks, and therefore efforts were made to auction mobile licenses. Overall, the efforts to extend telephone lines across Nigeria failed spectacularly within a broader context of insufficient investments, bureaucratic dysfunction, and the country’s persistent political crisis. Between 1985 and 2000, more than $5 billion was spent on digitalizing the telephone network that ended up with just 400,000 connected users for a population of 122 million people at the time. [9]

So, within this context, what was the catalyst for a change in mindset towards substantive reforms in the telecoms sector? I argue that external constraints on ruling elites enabled a pro-reform mindset to liberalize the sector. The business elites within the ruling coalition that stood to gain from liberalization also made the government more committed to the reforms, with Nigerian rather than international capital as central players. And this is how it all played out.

Despite professing a nominal commitment to liberalizing the telecoms sector, President Obasanjo only became committed upon realizing the potential for generating non-oil resources. His administration initially revoked the twenty-seven mobile operation licenses provided to investors by the previous military regime of General Abacha, which had placed Obasanjo on death row.[10] Therefore, the first attempt at GSM licensing in 2000 failed due to the power tussle among Obasanjo, former military ruler General Ibrahim Babangida, and other military elite. It was only when Obasanjo’s government realized the wealth-generation potential that a second bid round was conducted in the UK in 2001.[11] This is within a context in which Nigeria had limited fiscal resources due to low global oil prices and a heavy external debt burden, the servicing of which consumed nearly half of the annual budget. Specifically, Obasanjo’s government was encouraged by the high bids for the three licenses, each auctioned at $285 million, by Communication Investments, Econet Wireless Nigeria, and MTN. This amount far outstripped the $100m quoted for each license—the most expensive issued in Africa at the time according to the Econet CEO Strive Masiyiwa.[12] Thereafter, the administration became more committed to pursuing liberalization.

These external constraints also came from development partners and regional competition pressured the Obasanjo administration to liberalize the sector. Conditional assistance by the Bretton Woods institutions, OECD countries and the World Trade Organisation (WTO) facilitated liberalization. As a precondition for debt relief during low oil prices, Nigeria had to develop a reform strategy approved by the IMF. Consequently, in July 2000, the government pledged to minimize spending on restructuring NITEL as a precondition for a $1 billion standby agreement.[13] There was also neighborhood rivalry within West Africa. The realization that earlier failures had left Nigeria’s telecoms network several years behind those of Ghana, Ivory Coast, and other regional rivals may have expedited the GSM auctions in 2001.[14]

Given these external pressures, business elites in the ruling coalition shaped the direction of liberalization to be driven largely by domestic rather than international capital. Officials and business partners of previous military regimes owned shares in these first wave telecoms firms. For instance, Colonel Sani Bello (rtd.), a former military governor and ambassador and an oil tycoon, owned a minority stake in MTN Nigeria, one of the three beneficiaries of the 2001 auction.[15] Econet Wireless Nigeria (now Airtel Nigeria), the first telecoms firm to operate in Nigeria, had a consortium of twenty-two all-Nigerian financiers including Diamond Bank, the Lagos and Delta state governments, military generals who were founding members of the PDP, and industrialists such as Oba Otudeko, who had made fortunes during military rule in the 1980s.[16] Many multinational telecoms firms at that time were wary of investing in Nigeria given the widespread perception of fraud about the country. It wasn’t all rosy though, as there was bribery and underhand dealing in the license auctions. For instance, Econet Wireless Nigeria was asked to pay $9 million in bribes to senior politicians who mobilized financial investments for the license. According to the firm’s CEO Strive Masiyiwa, his refusal to authorize the illegal payments led to the cancellation of Econet’s management contract by Nigerian shareholders.[17] Another international operator was invited to replace Masiyiwa’s Econet as technical partner, the name was changed from Econet to V-Mobile, then to Vodacom, Zain, Celtel, and finally to Airtel today.

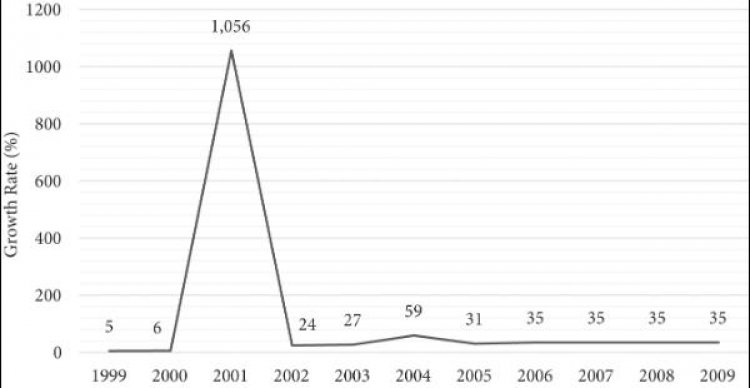

Figure 1. Growth Rate (%) of the Telecommunications Sector, 1999–2009.

The liberalization in August 2001, marked by the introduction of cellular networks, the Global System for Mobile (GSM), engendered the telecoms sector’s expansion. From 400,000 phone lines in 2000, there were 328 million connected mobile and fixed lines and 139 million internet subscriptions by July 2021,[18] the largest mobile market in Africa. The telecommunications sector expanded from just 0.1% of GDP in 2001 to 8.2% in 2019, growing at an average of 122% from 1999 to 2009 (Figure 1). Nigeria is the biggest market for the South African mobile firm Mobile Telecommunications Network (MTN), in terms of subscriber base, constituting about 27% of its 273 million subscribers across twenty-one countries.[19] Nigerian-owned Globacom, is a major player across Africa.

This involvement of domestic private sector was a watershed for market reforms in Nigeria as the business men allied to ruling elites championed the telecoms liberalization. They demonstrated their capacity to generate new resources or economic rents and to ease budgetary restraints, which although one-off, allowed key elites to position themselves in emergent economic sectors and created a model for replication in other sectors. In particular, the Dangote Conglomerate among others, as we discussed at the beginning, benefited from the allocation of monopoly rents in the cement and fruit juice industries through the “Backward Integration Policy” which allowed Nigeria became a net exporter of cement by 2013.[20] The counterfactual is that, even without the involvement of local financiers, GSM would eventually have spread to Nigeria, but would have been wholly led by multinational firms.

Therefore, through the political settlements lens, we identify how external constraints enabled the emergence of a growth coalition in Nigeria’s telecoms sector. At the turn of the century, a ruling coalition was able to drive market reforms in the telecommunications sector, despite oil wealth, ethnic pluralism, or the “neopatrimonial logic” which would otherwise obstruct growth. The story is, however, remarkably different in most parts of the oil and gas sector, particularly the downstream of petroleum refining, transportation, and distribution.

Distributional Pressures Prevent the Deregulation of Petroleum Prices and Effective Subsidy Reform

In Nigeria’s oil industry, reforms have been comparatively less effective. The sector overall has trended towards steady stagnation and decline. For instance, the oil sector grew at an average of 1.3% between 1999 and 2009, and -3% between 2010 and 2019 despite high overall economic growth until 2015. On the one hand, the oil sector’s decline as a share of GDP from a peak of 49% in 2000 to 9% in 2019 indicates diversification of output. However, the sector’s absolute decline points to a deeper malaise. Since 2013, production averaged 1.9 million bbl/d below peak capacity of 2.4 million bbl/d, and the target of 4 million bbl/d.[21] Nigeria’s proven reserves have not grown from 37.2 billion barrels despite targeting 40 billion barrels.[22] Oil earnings routinely disappear through leakages across the industry value chain. Nigeria lost $217.7 billion from 1970 to 2008, and $20 billion between 2010 and 2012.[23] The Petroleum Industry Bill meant to harmonize the disparate legislations governing Nigeria’s oil industry stalled for two decades before its passage in August 2021. A paper by political scientist Alex Gboyega, finds that “every institution along the extractive industries value chain that potentially could prevent fraud is weak. Although these weaknesses allow for manipulation, . . . the necessary underlying conditions for . . . best practice in petroleum governance are not in place. The responsibility is political.”[24]

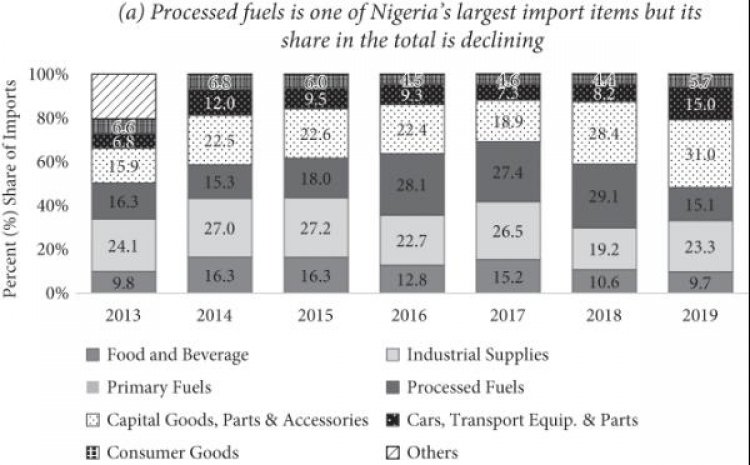

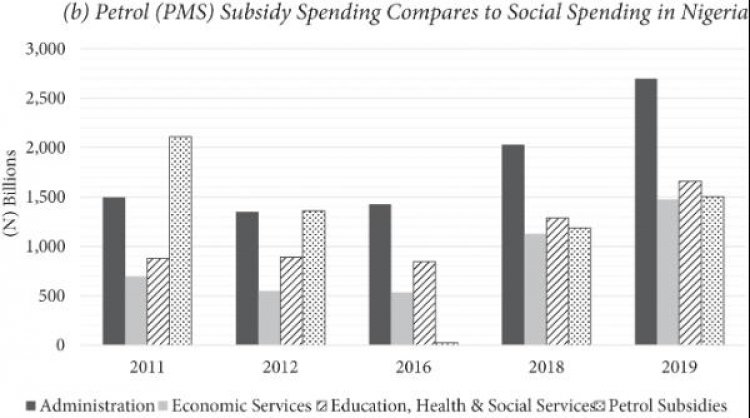

Specifically, the dysfunctions in the downstream sector of petroleum refining, transportation and distribution of Nigeria’s oil industry affect public finances and service delivery. These dysfunctions are at least threefold. First, Nigeria spends billions of dollars annually to secure fuel supplies to power economic activities. These fuels include premium motor spirit (PMS) or gasoline, automated gas oil (AGO) or diesel, household kerosene (HHK), aviation turbine kerosene (ATK) or jet fuel, and low-pour fuel oil (LPFO) among others. Therefore, it spends billions of dollars importing fuel, usually among the top three largest import items including capital goods and industrial supplies (Figure 2a) and also spends heavily on subsidizing the final consumer prices below market rates. In 2019, Nigeria spent N2.5 trillion importing processed fuels equivalent to 15% of total imports (Figure 2a). Although the 2019 figures mark a decline from the nearly 30% (N3.8 trillion) in 2018 and 27% (N2.6 trillion) in 2017, it is still very high. For fuel subsidies’ expenditure, the figures are hard to come by as they frequently spill into extra-budgetary spending. In 2011, for instance, Nigeria spent N2.1 trillion on PMS subsidies although it had budgeted only N245 billion for both PMS and HHK.

Figure 2. Nigeria Spends Billions of Dollars on Importing and Subsidizing Processed Fuels.

A second aspect of this dysfunction is that the billions spent on importing and subsidizing fuel come at the expense of public services, especially electricity and transportation infrastructure and social protection. These subsidies alone in 2011 were more than double the N878 billion spent on education, health and social services combined; and the N697 billion on agriculture, transport and other economic services (Figure 2b). Although the subsidy regime has been significantly cleaned up with a less-rigid pricing regime, closure of extra-budgetary leakages, and lower global oil prices, Nigeria still spent more than N1.5 trillion on this expenditure item in 2019.

Finally, any effort to drastically reduce spending on fuel subsidies is fiercely resisted by many Nigerians. Nigeria’s national trade unions, NLC and TUC, and those in the oil and gas sector PENGASSAN and NUPENG[25] often coordinate mass resistance to the removal of petroleum subsidies. While this advocacy is driven by concerns about rising costs of living associated with fuel price hikes, it often translates into hostility to broader reforms that introduce market forces in the downstream petroleum sector. Major increases in petroleum prices are accompanied by paralyzing strikes. Most notably, the partial removal of fuel subsidies in January 2012 which raised gasoline prices from N65/liter to more than N141/liter, led to unprecedented mass protests. Thousands of people poured out onto the streets in Nigeria’s major cities of Abuja, Benin, Kaduna, Kano, Lagos, Port Harcourt, and at Nigerian embassies abroad in the UK and the USA.[26] The protests tagged “Occupy Nigeria” pressured the government to partially restore the subsidies several days later. In light of this resistance, governments settle for incremental adjustments to the pump price of gasoline when convenient.

These dysfunctions in Nigeria’s downstream oil sector are rooted in certain structural characteristics of the economy which create redistribution pressures on policy makers to continue these suboptimal policies. These structural characteristics include a large demand for fossil fuels as a major energy source in the economy, a supply gap resulting from weak domestic refining capacity, and an unhealthy dependence on fuel imports to balance supply and demand.

Before we examine these structural characteristics, it is important to situate and contrast this discussion within the prevailing global discourse on fossil fuel subsidies. This reality of how fuel subsides are deeply intertwined with the structural characteristics of the Nigerian economy eludes many reform advocates who misdiagnose the reason why these subsidies persist. It is assumed that Nigerian decision-makers are irrationally pursuing a bad policy of maintaining the fuel subsidies that are: economically inefficient because they subsidize consumption, fiscally wasteful because they are prone to corruption, socially regressive because they benefit the urban middle class at the expense of the rural poor, and environmentally harmful because they encourage more consumption and higher emission of greenhouse gases.[27] Since 2010 or so, the policy literature and donor interventions have evolved to incorporate political-economy approaches to better understand how powerful actors can support or obstruct subsidy reforms.[28] I was part of several such initiatives during my time at the World Bank at a global level, and in Morocco, Nigeria, and Zambia.[29] Despite these analytical advances, these political-economy approaches to studying and reforming subsidies remain limited in their focus on the role of powerful stakeholders. These studies are not sufficiently in-depth in understanding how structural factors shape the behavior of these powerful actors.

My position goes thus: it is not just that decision-makers are irrational, ignorant of “good policies,” are bad communicators, susceptible to unethical tendencies or forever beholden to corrupt cronies, although all of these are partially true. The reality is that the mechanics of the way fuel imports and subsidies are intertwined with the quotidian activities in the Nigerian economy compel even the most well-intentioned decision-makers to retain them. Within this economy, policy makers are expected by Nigerians to keep fuel prices artificially low as a form of redistribution to cushion their inflationary impacts on the cost of living.

Let us now examine the structural characteristics of the downstream petroleum sector that compel the retention of fuel subsidies.

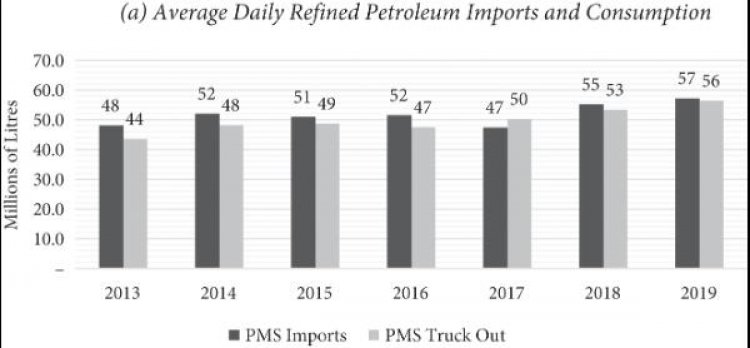

Despite being Africa’s largest oil producer, Nigeria is unable to meet its domestic demand for refined oil products, especially petroleum, diesel, and kerosene. On average, the country consumes 56 million liters of gasoline (PMS) daily for residential, productive, and transport uses (Figure 3a).

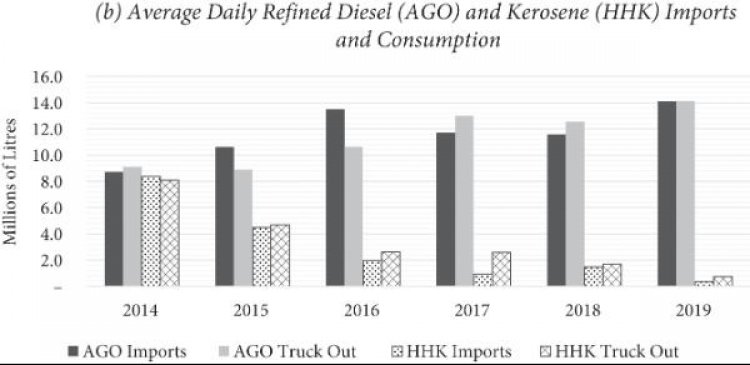

Figure 3. Average Daily Refined Fuel Imports and Consumption in Liters (millions), 2014–2019

Note: Truck Out is a proxy for consumption. It refers to the amount of fuel transported and distributed in trucks.

Nigeria’s 200-million-strong population translates into many fossil fuel consumers. Furthermore, fossil fuels are a main energy source for electricity generation for residential and productive uses, with gas and oil accounting for more than nearly 90%, according to the International Energy Agency.[30] Absent reliable grid power, private electricity generators powered by gasoline (PMS) and diesel (AGO) contribute to 32% of electricity generation in Nigeria. These fuels are also major energy sources for transportation, which itself accounts for 80% (17.8 million tons of oil equivalent Mtoe) of total fossil fuel final energy consumption (22.2 Mtoe).[31] With insufficient mass transit systems, Nigerians rely on their individual solutions to intracity and interstate transportation such as passenger vehicles and light trucks, the second highest in sub-Saharan Africa in 2015.[32] Although there has been a recent push to complete inter-city rail networks, such as the Abuja-Kaduna Rail; the Itakpe–Ajaokuta–Warri Rail, and the Lagos-Ibadan Rail Project, Nigeria lags on effective and reliable mass transit systems, including urban transit, for its size and income. Finally, Nigeria also consumes large volumes of HHK as cooking fuel for lower-income households (Figure 3b). It is used in stoves and complements the coal, firewood, and other biomass that collectively account for more than 73% of cooking fuels, in the absence of cleaner energy options.[33] Therefore, there is a large demand for refined oil products for residential, productive, and transportation uses due to structural attributes of a large population, a deficit of electricity and mass transit systems, and lack of affordable clean cooking fuels.

A second structural attribute of the downstream petroleum sector is that this large demand for fossil fuels in Nigeria is not met by domestic refining capacity. In other words, there is a supply gap for petroleum and kerosene, and until recently, diesel. Taking petroleum in particular, Nigeria consumed an average of 56 million liters daily in 2019, of which it imported 57 million liters (Figure 3a). The discrepancy between the imports and final consumption is not a glitch—Nigeria tends to import more fuels than it consumes due to the byzantine nature of the downstream sector. As several policy makers explained to me, imported and subsidized fuels are illicitly re-exported at higher prices to neighboring West African countries through the Republic of Benin.[34] West Africa consumes 22 billion liters of PMS annually of which imports account for over 90%.[35] In theory, Nigeria should be able to supply its own domestic needs from its refineries. It has five operational refineries of which four are NNPC-state-owned, with a combined installed capacity of 446,000 bpd per day. These are spread across the country’s vast landscape in Kaduna in the north, three in Port Harcourt and Warri in the south, and a fifth, private 1,000 bpd complex (Table 1). At present, Nigeria has Africa’s fifth-largest refining name-plate capacity after Egypt, Algeria, Libya, and South Africa, although actual output is very low.

Table 1. Status of Nigeria’s Public and Private Refineries.

| Refineries | Number | Description | Capacity | Status |

| NNPC Refineries | 4 | Conventional plant capable of producing transportation fuels PMS, HHK, AGO; heating oils’ LPFO, and petrochemicals. | 445,000 | Operational |

| Niger Delta Petroleum Resources | 1 | Modular plant capable of producing naphtha, dual purpose kerosene (DPK), AGO, marine diesel, Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG). | 1000 | Operational |

| Dangote Oil Refinery Company |

1 | Conventional plant capable of producing transportation fuels PMS, HHK, AGO; heating oils’ LPFO, and petrochemicals. | 650,000 | Advanced construction stage, nearing completion |

| Other Conventional Refineries with Active Licenses |

5 | Conventional plant capable of producing transportation fuels PMS, HHK, AGO; heating oils’ LPFO, and petrochemicals. | 700,000 | At various stages of construction |

| Modular Refineries with Active Licenses |

20 | Modular plants capable of producing naptha, PMS, HHK, AGO, LPFO, and LPG | 295,000 | At various stages of construction |

| Refineries with Expired Licenses (All Modular) |

17 | Modular plants capable of producing naptha, PMS, HHK, AGO, LPFO, and LPG. | 655,000 | Mostly sourcing funds with some at early stages of construction |

| Grand Total | 48 | 2,746,000 | ||

| Total excl. NNPC | 44 | 2,301,000 |

||

| Total Modular Refineries | 38 | 951,000 | ||

| Total Conventional Refineries Excl. NNPC | 10 | 1,350,000 |

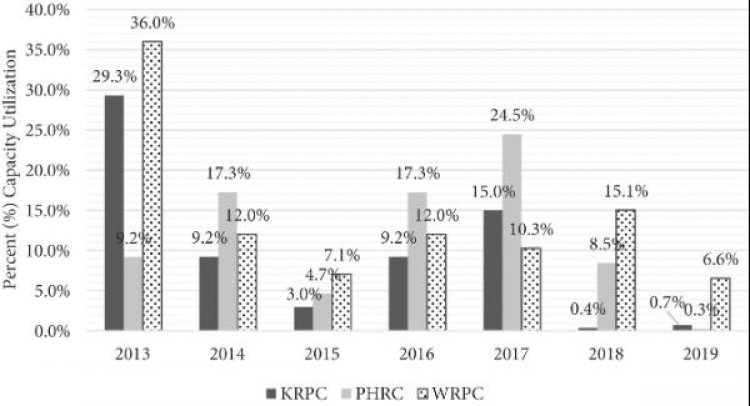

Figure 4. NNPC Refining Capacity Utilization (%), 2013–2019.

Note: KRPC—Kaduna Refinery and Petrochemical Company; PHRC—Port Harcourt Refinery Company; WRPC— Warri Refinery and Petroleum Company.

Since the late 1990s, these NNPC refineries have operated at way below capacity with deteriorating performance although recent private investments could soon ramp up output. In 2019, the combined capacity utilization of the four state-owned refineries was less than 10% (Figure 4). Various efforts at rehabilitating the government refineries, through Turn Around Maintenance (TAM) over the last two decades have been costly and unsuccessful. In 1997, Abacha’s regime awarded a $215 million contract for the Kaduna refinery. In 1998, the Abdulsalam regime awarded a $92 million contract for the four refineries. Under Obasanjo $254 million was spent on them. Nearly 140$ billion in 2011 and $1.6 billion in 2013 were spent under Goodluck Jonathan.[36] An attempt at privatization in the twilight of the Obasanjo administration in May 2007 was immediately reversed by the successor Yar’Adua government for various reasons including an ideological aversion to a full market orientation in commanding heights of the economy and fears that Obasanjo was conducting a fire sale of national assets to cronies.

Since 2004, forty-four (six conventional and thirty-eight modular refinery) licenses with a combined capacity of 2.3 million bpd have been issued to domestic and private investors (Table 1).[37] Of the thirty-eight low-cost modular refinery licenses, only the Ogbele Refinery by the Niger Delta Petroleum Resources with a 1,000-bpd capacity is operational; a few others are nearing completion. Among the six conventional refineries, only the Dangote Petroleum Refinery Company is at an advanced stage of construction (see Box 1). If completed, the Dangote Refinery alone could address Nigeria’s supply gap for refined oil products and help realign incentives around downstream oil sector reforms. The modular refineries, which have smaller capital outlays and are more labor intensive, can help support private-sector development, job creation, and address illegal oil refining and its associated environmental degradation in the Niger Delta. Overall, if these refineries were to be completed and become operational at even 50% combined capacity of 1.35 million bpd, they could address the supply gap for refined fuels in the whole West Africa sub-region.[38] Nigeria could become one of Africa’s top three largest producers and exporters of refined fuels and petrochemicals with spill over effects for jobs and industry. Until then, nearly all of Nigeria’s demand for refined fuels is met by imports rather than local refining.

Box 1: Can the Dangote Petroleum Refinery Help Address the Dysfunctions in the Downstream of Nigeria’s Oil Industry?

The Dangote Oil Refinery could be one of the solutions to addressing the supply gap for refined fuels in Nigeria. It is a 650,000 bbl/day integrated refinery project under construction in the Lekki Free Zone near Lagos in Nigeria. The project is set to be Africa’s largest oil refinery and the world’s biggest single-train facility. A license was approved after an unsuccessful attempt to acquire the Kaduna and Port Harcourt refineries in May 2007 through a consortium, called Bluestar, for $750 million in the twilight of the Obasanjo administration.[39] In 2013, Dangote signed a financing deal with a consortium of local and international banks to begin construction for his new refinery. Total costs are estimated to reach $19 billion. Despite various challenges, including the sharp currency devaluation that accompanied the collapse of global oil prices from 2015 and extended timelines, the complex is scheduled for completion in late 2022. The refinery holds the promise of addressing some of the debilitating dysfunctions in the downstream of Nigeria’s oil industry and of alleviating the burden on government revenues. With a capacity to process 650,000 barrels of oil daily, the refinery can bridge the supply gap for petroleum, kerosene, and other fuels that power quotidian economic activities. It can also export the surplus across the West Africa sub-region, as the cement industry, thereby easing pressures on Nigeria’s foreign reserves. Crucially, boosting domestic refining could eliminate other costs around imports, transportation and distribution that may finally make fuel subsidies redundant. The implication thus is of an impending removal of fuel price controls to allow market forces prevail for the refinery to turn a profit. Finally, the refinery will create jobs in the domestic economy, as Aliko Dangote explained to me. This is estimated at 4,000 direct and 145,000 indirect jobs around production, transportation, and distribution of the fuel products as well as auxiliary services like real estate and hospitality. These benefits notwithstanding, there are risks to the success of the refinery and to Nigeria’s oil industry overall. Nigeria’s challenging business environment could derail the project’s successful completion, take-off, and profitability. For instance, congested ports at Lagos delayed by more than three years the project’s initial completion date and infrastructure constraints resulted in the relocation of the refinery site. Dangote is pulling all the stops to mitigate these challenges. The refinery is funded by a combination of equity ($3 billion), debt financing ($6 billion) from local and international banks and a $2.7 billion equity investment by the NNPC, including a $1 million grant to develop human resources from the United States Trade and Development Agency. It will feature its own infrastructure such as a pipeline system, access roads, tank storage facilities, and crude and product-handling facilities; a marine terminal, and a fertilizer plant.[40] Given Dangote’s antecedents in import substitution in the cement industry, this refinery could transform the regulated downstream oil sector into a monopoly. With its sheer scale, the refinery will easily have the dominant market share for fuels and petrochemicals in most of West Africa potentially restricting competition. If the refinery does succeed as intended in helping eliminate fuel imports and the associated subsidies, new risks could arise from the stakeholders who lose out of this new equation. In other words, powerful actors such as fuel traders who are suddenly cut off from their lucrative enterprise could organize politically to resist this new economy that excludes them. These potential grievances combined with full deregulation that results in higher fuel prices, could be leveraged by politicians to undermine the social legitimacy of the Dangote Refinery, and the conglomerate more broadly. Finally, there are risks to the environment from the refinery’s carbon emissions and industrial waste. The global transition underway towards cleaner energy could render a refinery of this scale redundant and its assets stranded in a future powered by clean energy. Overall, the Nigerian government has an important regulatory role to play in anti-trust initiatives, consumer rights, environmental protection, and public service provision.

A final underlying characteristic of Nigeria’s downstream oil sector is that the large gap in supplies for refined fossil fuels for domestic consumption is bridged through imports. Nigeria imports nearly all the 56 million liters of PMS, 14.1 million liters of AGO and 740,000 liters of HHK it consumes daily (Figure 3a/b). These imports are undertaken in institutionally opaque and fiscally wasteful circumstances. Through the NNPC, the government barters 210,000 barrels of crude oil per day that are neither exported nor provided to domestic refineries, in exchange for refined PMS, HHK, and other derivatives. This barter arrangement became widespread from 2010 when the performance of the four state-owned refineries severely deteriorated. Thus, large volumes of fuel were imported to meet daily demand and prevent a return to the dreaded long queues at petrol stations that were ubiquitous in the 1990s. Initially, this barter took the form of short-term “oil-for-product swap” or “offshore processing agreements” between various arms of the NNPC and commodity traders. These traders include Aiteo Energy Resources, Duke Oil, Nigermed, Sahara Energy, Societe Ivorienne de Raffinage (SIR), and Trafigura.[41]

The terms of some of these secretive crude swap agreements have been very unfavorable to Nigeria. The American NGO, NRGI, estimates losses of up to $381 million in one year (or $16 per barrel of oil) from just three provisions in one of the seven crude swap contracts Nigeria entered into between 2010 and 2015.[42] Some of the contracts also contained troubling clauses, such as those that permit “destruction of documents after one year.”[43] After the scandal around subsidies exploded in 2012, the crude swaps were replaced in 2016 with a more transparent and cost-effective Direct-Sale-Direct-Purchase (DSDP) arrangement in which the NNPC directly sells crude oil to refiners and purchases refined oil products from them.[44] Yet, the DSDP still involves some of the same commodity traders that exploited Nigeria in the past, and will continue until at least 2023 when it is expected that domestic refining capacity would have improved.

Until 2016, private-sector actors were also involved in importing refined fuels. Since at least the 1970s, the government provides import licenses to businessmen to buy refined petroleum from abroad and distribute to the domestic market. For a long time, the import license regime was riddled with cronyism, opacity, inefficiencies, and severe revenue leakages. An investigation by the lower chamber of the federal legislature in 2012 found that the number of private importers of refined fuels increased exponentially from 6 in 2006 to 19 in 2008 and 140 in 2011; and marketers who distribute these fuels increased from 45 in 2009 to 128 in 2011.[45] In one egregious instance, one hundred and twenty-eight payments of equal installments of N999 million each were made within twenty-four hours in January 2009, to unknown beneficiaries involved in the import trade that did not supply a drop of oil.[46] Fuel import and marketing licenses became a way of dispensing patronage during a period of high oil prices from 2010 and a tense political environment after President Yar’Adua’s death and right before the 2011 elections when the PDP’s northern caucus opposed to Jonathan’s presidential bid. Unsurprisingly, the list of twenty-three oil marketers investigated at the time included the sons of two former PDP chairmen, Senator Ahmadu Ali and Bamanga Tukur.[47] Although the regime of private-sector fuel importers has been cleaned up since 2016, the transportation and distribution system to get the product to vendors and the final consumer is still maddeningly inefficient and byzantine.

Let us now tie up this intricate information together. Due to these structural characteristics of Nigeria’s downstream petroleum sector, decision-makers are constrained to continue spending billions of dollars to subsidize fuel imports to meet domestic demand. The exact expenditure on fuel subsidies is unknown because it is a complicated expense item that spills beyond the actual annual budget. For instance, the NNPC documents that N780 billion was spent on subsidizing PMS imports in 2019, but the Senior Special Assistant to the president announced a figure closer to N1.5 trillion.[48] The amount spent on subsidies closely tracks global oil prices, with higher expenditures during high oil prices, such as between 2011 and 2013 when oil was over $100 per barrel and vice versa during low oil prices, bearing in mind the leakages and inefficiencies (Figure 2b). So, it is not that policy makers are unaware of the waste and inefficiencies in the fuel subsidy regime as some economists and donors tend to assume. Without addressing the underlying structural characteristics of the downstream oil sector around the infrastructure deficiencies driving demand, the fuel supply gap resulting from weak domestic refining capacity and thus the reliance on a deeply flawed import regime, it is nearly impossible for any government administration to effectively reform fuel subsidies.

Even severe external fiscal pressures on policymakers from the sudden collapse of oil prices, are insufficient to drive sustained reform of the subsidy regime which is a core element of Nigeria’s social contract. Each government during the last twenty years, regardless of political affiliation or ideological orientation has announced the removal of these subsidies but with little to no actual reforms taking place. The Buhari administration announced in June 2020 that it had effectively ended all fuel subsidies.[49] In principle, subsidy payments decline significantly with low global oil prices. This should be the opportunity to painlessly remove price controls and then allow market forces to prevail with an effective communications campaign to convey to the public, the movement of global prices. Yet, no government can withstand the intense pressures to restore these subsidies from Nigerians experiencing the inflationary impacts of rising electricity and transportation costs from higher fuel prices. As some recent studies have shown, given these severe structural constraints, subsidy removal has inflationary impacts that are detrimental to the poor, to households, and, most importantly, to the productivity of firms.[50] According to a World Bank assessment, successive Nigerian governments have aimed to provide benefits to the population in the form of lower fuel prices, which can directly affect welfare through savings on fuel expenditure, as well as bring indirect benefits through lower costs of transportation.[51] Even well-designed communications campaigns, as are often suggested by donor interventions, are insufficient to compensate for the absence of electricity, transportation, and social protection for the poor.

Overall, the downstream oil sector consumes Nigeria’s fiscal revenues, undermines service delivery, and undercuts the sector’s efficiency. From this discussion, the problem in Nigeria’s downstream sector is not, as is often framed by much academic and policy-oriented scholarship, of an unhealthy dependence on wasteful and inefficient fuel subsidies. It is not the fuel subsidies that cause the dysfunctions around refining, distribution, and large-scale consumption of fossil fuels. It is rather the structural attributes of the Nigerian economy. The dependence on fuel subsidies is not an immutable characteristic of a country afflicted by a “resource curse” since an oil-rich country like Iran was, from 2010, able to establish an effective cash transfer program for poor households to compensate for the removal of petroleum subsidies.[52] The direction of causality is the reverse.

The unhealthy dependence on these inefficient subsidies is caused by a structural dysfunction in the downstream sector resulting from insufficient infrastructure and public services. Nigerian policymakers could have used the billions of dollars wasted in the maintenance of the obsolete refineries. They could have adopted a phased approach to reallocating subsidy expenditure towards policy solutions to address these structural problems. For instance, investing in electricity provision, mass transit, petroleum refining and expanding social protection coverage to renew the social contract with society beyond an unhealthy dependence on wasteful subsidies. Thus, policymakers are frequently in a conundrum, they understand that petroleum subsidies are wasteful expenditures on consumption. When constrained by fiscal pressures, their immediate policy response is to remove subsidies without addressing the structural factors. This knee-jerk reform receives a swift backlash from Nigerians bearing the brunt of inflationary impacts until the subsidies are restored. Hence the vicious cycle and blame-game continues.

Conclusion

To conclude, the diversification of Nigeria’s economy towards a post-oil future lies in its recent successes and failures in reforming specific sectors. The varied experience of successfully liberalizing the telecoms sector while struggling to reposition the oil industry provides insights into the mechanics of economic reforms in Nigeria. Whether certain reforms are successfully implemented owe to the political constraints on policymakers that incentivize them to pursue a specific course of action to empower capable entrepreneurs such as the telecoms investors. External constraints of global oil prices that created a severe revenue crisis motivated the ruling elite to overcome internal squabbles and quickly liberalize the telecoms sector with domestic capital and foreign technology in the front seat. Declining revenues at the critical juncture of democratization in 1999–2000 and also from 2015 have not constituted sufficient pressures for a radical overhaul of the oil industry, especially the downstream sector of petroleum refining, transportation, and distribution. The vertical–societal pressures for cheap fuel to compensate for the absence of electricity access, mass transit systems, and social protection services prevailed in disincentivizing sustained reforms. However incremental policy changes including the provision of refinery licenses and the completion of some refineries in the next few years may gradually allow Nigeria to address its domestic fuel supply gap, and thereby reorient incentives of ruling elites around substantial oil sector reforms.

Note: This is an excerpt from the book “Economic Diversification in Nigeria: The Politics of Building a Post-Oil Economy” by Zainab Usman, published by Bloomsbury Publishing, 2022, with minor edits.

About the Author

Zainab Usman

Zainab Usman is director of the Africa Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Washington, DC.

Notes

[1] Author interview, Lagos, 20 March 2014.

[2] U.S. Embassy Abuja (Nigeria: Tariff and Ban Information, 2003).

[3] Sahara Reporters (CBN’s List of Bank Debtors, 2009).

[4] Dangote Group (About Us, 2020).

[5] Forbes (#191 Aliko Dangote, 2021).

[6] Akinyinka Akinyoade and Chibuike Uche argue that Dangote’s entrepreneurial skills explain his success in cement manufacturing (Dangote Cement: An African Success Story?, 2016).

[7] U.S. Embassy Lagos (Aliko Dangote and Why You Should Know about Him, 2005).

[8] Taiwo A. Gbenga et al. (Privatization and Commercialization of Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation Oil Refineries in Nigeria, 2014).

[9] William Wallis (The Telecoms Numbers that Didn’t Add Up, 2013).

[10] BBC News (Nigeria Awards Telecoms Licenses, 2001).

[11] Interview with an advisor for Obasanjo’s government, Abuja, 13 May 2014.

[12] Strive Masiyiwa (It’s Time to Play by a Different (Ethical) Set of Rules (Part 7) Nigeria I, 2015).

[13] Chukwudiebube Opata (Transplantation and Evolution of Legal Regulation of Interconnection Arrangements in the Nigerian Telecommunications Sector, 2011).

[14] BBC (2001).

[15] On share ownership for the pioneering telecoms firms, see: Masiyiwa (2015) and Fola Akanbi (Forbes: Nigerian New Entrants to Rich List Grew Wealth through Investments in Oil and Gas, 2012).

[16] Ibid.

[17] See: Masiyiwa (2015).

[18] Nigeria Communications Commission NCC (Subscriber Statistics, 2021).

[19] MTN Group Limited (Quarterly Update for the Period Ended 30 September 2020, 2020).

[20] Crusoe Osagie (Nigeria: As Dangote Transforms Nigeria into an Export Nation, 2015).

[21] CBN (Annual Economic Report for 2013, 2013).

[22] U.S. Energy Information Administration—EIA (Nigeria, 2013).

[23] AU and ECA (Report of the High Level Panel on Illicit Financial Flows from Africa, 2014) and Sanusi L. Sanusi (Memorandum Submitted to the Senate Committee on Finance on the Non-Remittance of Oil Revenue to the Federation Account, 2014).

[24] Alex Gboyega et al. (Political Economy of the Petroleum Sector in Nigeria, 2011, p. 15).

[25] The key unions in the sector are the Petroleum and Natural Gas Senior Staff Association (PENGASSAN) and the Nigerian Union of Petroleum and Natural Gas Workers (NUPENG). They represent the white-collar and blue-collar workers respectively.

[26] Busari (What is Behind Nigeria’s Fuel Protests?, 2012).

[27] These are mostly econometric analyses on economic impacts, see: Michael Plante (The Long-Run Macroeconomic Impacts of Fuel Subsidies, 2014); on social and distributional impacts, see: Francisco Javier Arze del Granado, David Coady and Robert Gillingham (The Unequal Benefits of Fuel Subsidies: A Review of Evidence for Developing Countries, 2012) and Ismail Soile and Xiaoyi Mu (Who Benefit Most from Fuel Subsidies? Evidence from Nigeria, 2015); on environmental impact, see: David Coady, Ian Parry, Louis Sears, and Baoping Shang (How Large are Global Energy Subsidies?, 2015).

[28] See for instance: David Victor (The Politics of Fossil-Fuel Subsidies, 2009); Masami Kojima (Fossil Fuel Subsidy and Pricing Policies: Recent Developing Country Experience, 2016), Gabriela Inchauste and David Victor (The Political Economy of Energy Subsidy Reform, 2017) and Harro van Asselt and Jakob Skovgaard (The Politics of Fossil Fuel Subsidies and their Reform, 2018).

[29] See for instance, background papers and report published as part of the Rethinking Power Sector Reforms in the Developing World Project: www.worldbank.org/en/topic/energy/publication/rethinking-power-sector-reform.

[30] International Energy Agency—IEA (Nigeria Energy Outlook, 2019).

[31] Ibid.

[32] Anthony Black, Brian Makundi and Thomas McLennan (Africa’s Automotive Industry: Potential and Challenges, 2017, pp. 12–16).

[33] IEA (2019).

[34] Author interviews.

[35] Olumide Adeosun and Ayodele Oluleye (Nigeria’s Refining Revolution, 2017, p. 4).

[36] Felix Jaro and Noma Garrick (Privatisation of Refineries: the Panacea to Nigeria’s Refining Problems?, n.d.).

[37] Modular refineries are available in capacities of 1,000–30,000 bpd, have low capital requirements of around $100–$200 million, can be constructed within a short time span of under twenty months, and provide for flexibility to be built and upgraded in a phased manner. Conventional refineries by contrast are usually larger with capacities higher than 100,000 bpd, require larger capital investments and specialized labor to run, maintain and upgrade, and also allow for economies of scale and thus higher margins on products (Adeosun and Oluleye, 2017, p. 12).

[38] Olumide Adeosun and Ayodele Oluleye (Nigeria’s Refining Revolution, 2017).

[39] Tume Ahemba (Obasanjo Ally Buys Second Nigerian Oil Refinery, 2007).

[40] Hydrocarbons Technology (Dangote Refinery, Lagos, 2020).

[41] Aaron Sayne, Alexandra Gillies and Christina Katsouris (Inside NNPC Oil Sales: A Case for Reform in Nigeria, 2015, pp. 42–43).

[42] Ibid.

[43] Sanusi (2014, p. 3).

[44] Elisha Bala-Gbogbo and Anthony Osae-Brown (Nigeria to Keep Oil-for-Fuel Swap for at Least Three More Years, 2019).

[45] House of Representatives (Report of the Ad-hoc Committee “To Verify and Determine the Actual Subsidy Requirements and Monitor the Implementation of the Subsidy Regime in Nigeria”).

[46] HoR (2012, p. 7).

[47] Ike Abonyi and Akinwale Akintunde (Subsidy Fraud: EFCC to Prosecute 23 Oil Marketers, 2012).

[48] Michael Eboh (FG Spent N1.5trn to Subsidise Petrol in 2019— Enang, 2020).

[49] Eklavya Gupte (Nigeria’s President Confirms Removal of Gasoline Subsidies, 2020).

[50] On public support for fuel subsidies, see: Neil McCulloch, Tom Moerenhout, and Joonseok Yang (Fuel Subsidy Reform and the Social Contract in Nigeria: A Micro-economic Analysis, 2020), on impacts on firm productivity, see: Morgan Bazilian and Ijeoma Onyeji (Fossil Fuel Subsidy Removal and Inadequate Public Power Supply: Implications for Businesses, 2012).

[51] World Bank (Advancing Social Protection in a Dynamic Nigeria, 2020, p. 26).

[52] Priscilla Atansah, Masoomeh Khandan, Todd Moss, Anit Mukherjee, and Jennifer Richmond (When do Subsidy Reforms Stick? Lessons from Iran, Nigeria and India, 2017).