Summary

- Multilateral development banks’ trade finance support programs, changes in trade value, and global banking regulatory changes drive the evolution of Africa’s trade finance gap.

- While the decline in commodity prices may have partly decreased demand in Africa’s trade finance, the global policy response to shore up trade credit for developing economies may have helped lower Africa’s trade finance gap for the period 2011–16.

- COVID-19-related uncertainties may drive the trade finance gap in Africa above its long-term trend of US$91 billion.

- Reclassification of trade finance as a less-risky asset class may reduce the capital burden on banks, encourage more banks to participate in the trade finance sector, and increase Africa’s trade finance inflows.

- There is an urgent need to establish an interoperable credit system that allows banks to share and access records on exporters and importers in real-time. Although it will require a substantial initial investment to set up, it might drive down banks’ AML/KYC compliance costs.

Introduction

About 80% of world trade relies on some form of trade finance, but the distribution is far from even. Firms in low-income economies consistently list the lack of access to finance among the top three export challenges. Using unique data from more than 600 banks in 49 countries in Africa from 2011 to 2019, a new report from the African Development Bank and Africa Import-Export Bank titled “Trade Finance in Africa: Trends Over the Past Decade and Opportunities Ahead” presents a view of the trade finance gap in Africa over the past decade and the factors that drive its evolution.

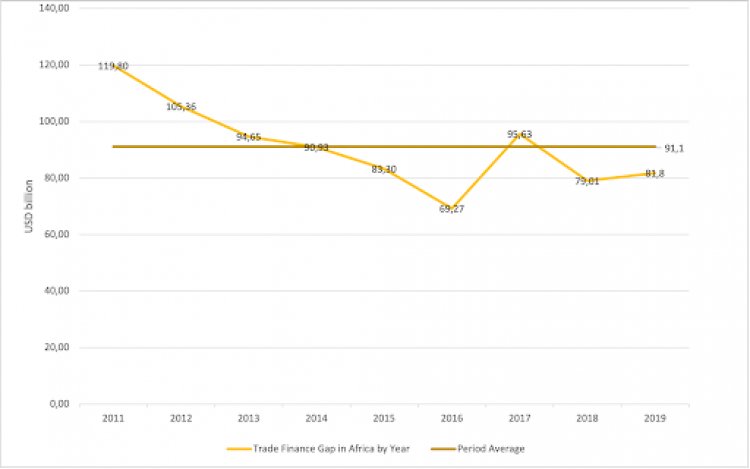

Trade Finance Gap in Africa. Source: AfDB-Afreximbank 2020. Trade Finance in Africa: Trends Over the Past Decade and Opportunities Ahead.

In 2011, the trade finance gap was estimated at US$120 billion; it decreased slowly but steadily to US$70 billion in 2016. But the downward trend in unmet demand reversed in 2016 and has shown some moderate fluctuations since then. While the estimated trade finance gap for the period 2018–19 is below the nine-year average of US$91 billion, it remains high relative to what the region’s share of world trade would predict. In 2019 a conservative estimate put unmet trade finance demand at about US$82 billion. Given that total African merchandise trade and global trade finance gap were estimated at US$1 trillion and US$1.5 trillion, respectively, unmet trade finance demand in Africa represented close to 8 percent of the region’s total trade value and 5.5 percent of the global trade finance gap in 2019. While 5.5 percent may appear low at first glance, it is worth noting that Africa’s trade accounts for only 3 percent of global trade, so its share of the global trade finance gap is disproportionately larger than the region’s share of world trade.

To understand the evolution of the trade finance gap in the region, one must look at the global policy framework that has shaped the trade finance landscape in Africa and beyond since the global financial crises.

The global policy response to the great trade collapse may have helped lower the trade finance gap in Africa for the period 2011–16. For a start, the slow but steady decrease of the trade finance gap for the period 2011–16 reflects the awareness raised about unmet demand following the global financial crises of 2008. World trade experienced a sudden and synchronous collapse in 2008–09. There is evidence that trade credit challenges were the No. 2 cause of the “great trade collapse,” second only to the collapse in demand. But while Europe and North America recovered quickly, the credit challenges remained persistent for Africa and, to some extent, Eastern Europe. Indeed, Africa was the only region that was still experiencing declining trade finance supply in mid-2009.

The policy response to shore up trade credit for developing economies was swift and extensive. Major multilateral development banks (MDBs) launched a combined US$9 billion in trade finance facilities that provided over US$80 billion in support for global trade (Mora and Power, 2009). Large commercial banks such as Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation (SMBC) of Japan also adopted measures to help lower the gap with “follow your firm” strategies, in which foreign banks followed their domestic firms to ensure that trade transactions initiated between Western firms and African counterparts had the necessary financial resources that made trade contracts viable. MDB interventions have persisted well beyond the global trade collapse, with the International Finance Corporation, African Development Bank, and Asian Development Bank having dedicated trade finance support facility programs to this day. African banks have been major beneficiaries of these interventions, which have helped shore up trade finance supply in the region.

The decline in commodity prices partly created an exogenous decrease in trade finance demand between 2011 and 2016. Between 2012 and 2016, total African trade decreased by an average of 6 percent a year, with the trade finance gap also falling by about 10 percent for the same period. Indeed, 2016 saw the lowest value of total African trade of about US$848 billion, mainly due to the decline in commodity prices that began in mid-2015. Not surprisingly, it was also the year in which the trade finance gap was lowest, at US$69.3 billion. As the value of African trade fell, the implication was that it resulted in an exogenous decrease in the aggregate demand for trade finance in Africa, driving down the wedge between trade finance demand and supply.

However, the recent uptick in the trade finance gap may reflect changes in the regulatory landscape. The year 2017 saw the reversal of the downward trend in the global trade finance gap. Undoubtedly, this reversal is not confined to Africa but is reminiscent of the deteriorating global trade finance landscape globally. Recent figures published by BNY Mellon and ADB show that trade finance rejection rates are increasing globally (hence the gap), with a third of banks citing compliance and KYC constraints as key drivers for rejection (BNY Mellon, 2019). A higher rejection rate, by definition, increases the trade finance gap. Here, the uptick in the gap from 2016 could reflect the impact of changing global banking regulatory environment. As African countries move to adopt new Basel III banking regulations that have come into force, especially with the treatment of trade finance as a riskier form of asset class under Basel III, small banks are shunning the trade finance sector and global correspondent banks that play a crucial role in African trade are retreating from the continent.

In the case of Africa, stringent capital requirements on trade finance assets from Basel III and new anti-money-laundering/know-your-client (AML/KYC) compliance measures have resulted in higher due diligence costs and lower margins, which has reduced the number of banks that engage in trade finance activities. The share of banks that engaged in trade finance in Africa fell from 92 percent in 2014 to a low of 71 percent in 2019—a decrease of 21 percent points.

For banks that remained in the trade finance sector, higher costs and lower margins have made small transactions less profitable, especially for small banks with higher average costs. This has led to an increase in rejection rates, particularly for SMEs, and by definition, a reduction in trade finance supply. Historically, it was thought that a higher than normal trade finance rejection rate for SMEs resulted from the SMEs’ poor creditworthiness. But a peculiar feature of recent SME trade finance activity is that while the SME trade finance risk profile in Africa has improved, with the default rate falling from 14 percent in 2014 to 10 percent in 2019, the rejection rate for SME trade finance application has increased from 21 percent to 40 percent for the same period, suggesting that there is more to the SME trade finance rejection rate than weak creditworthiness.

The impact of regulatory challenges extends to correspondent banking relationships, too. Banks that provide the liquidity and risk-mitigation facilities that underpin global trade are gradually scaling back activities from riskier markets – particularly in Africa – as they go through a “de-risking” process due to increasingly stringent AML/KYC regulations and capital requirements. Barclays PLC’s exit from the region was much publicized in 2016. Indeed, about 20% of African issuing banks list correspondent banking relationships as the key constraint to trade finance supply.

The trajectory of the trade finance gap under COVID-19

With recent uncertainties introduced by COVID-19, the future trajectory of the trade finance gap remains difficult to predict. But there are reasons to fear that the pandemic could reverse some, if not all, of the progress that has been made, driving the trade finance gap above its long-term trend of US$91 billion. First, as the balance sheets of African firms deteriorate due to COVID-19-related challenges, banks may become reluctant to lend to them. Even when banks can meet the trade finance needs of firms, the measures put in place to combat the pandemic sometimes make it difficult to process such transactions promptly. Therefore, it is critical that policymakers continue to pull resources together to ensure that, at the minimum, the trade finance deficit does not increase. Ideally, we would continue to bring it down.

The good news is that based on lessons learned in the past, MDBs have again responded swiftly to the COVID-19 related challenges to trade finance. Of the US$1.35 billion set aside by the AfDB for rapid COVID-19 response in the private sector, USD270 million is earmarked for trade finance support. This is in addition to the existing guarantee capacity of more than US$700 million. Similarly, the International Finance Corporation’s Global Trade Finance Program has at least US$2 billion additional capacity to cover payment risks associated with trade finance globally. The trade finance sector is tapping into these resources, and MDBs have worked hard to provide support without delay as the pandemic progresses.

Recommendations for reducing the trade finance gap and future research

Reducing the trade finance gap in Africa requires understanding of the factors that drive its evolution. MDB trade finance support programs, falling trade value, and global banking regulatory changes have played key roles in the evolution of the trade finance gap in the region. MDB support has increased trade finance supply and lowered the trade finance gap since the great trade collapse. Falling trade value since 2012 has reduced the demand for trade finance, while recent banking regulations have increased cost and reduced margins, and in so doing, forced some banks to shun trade finance activities and others to increase rejections of small transactions.

If further progress is to be made in lowering the trade finance gap, regulatory challenges would have to be addressed, including potential reclassification of trade finance as a less risky asset class. This could reduce the capital burden on correspondent and small banks, encourage more banks to participate in the trade finance sector, and reduce the rejection of small transaction.

In addition, although stringent AML/KYC compliance measures are steps in the right direction in reducing illicit financial flows through misclassification of trade transactions, their impact on trade finance processing should be recognized, especially for small banks. Because strict compliance measures drive up due diligence costs, it forces less-productive banks to shun the trade finance sector. Support is therefore needed to minimize the cost of AML/KYC compliance. One way to do so is to consolidate the credit records of firms with interoperable credit systems that allow multiple banks to share and access records on exporters and importers in real time. This will partly drive down processing costs, although it should be acknowledged that it will require a substantial initial investment.

About the Authors

Eugene Bempong Nyantakyi is an Economist at the African Development Bank. His research interests include international trade, trade finance, entrepreneurship, and private sector development. He holds a Ph.D. in Economics from West Virginia University.

Omolola Amoussou is a Principal Research Economist at the African Development Bank. Prior to joining the African Development Bank, she was a manager at the Financial Risk Management Practice at PricewaterhouseCoopers in Washington DC. She holds a Ph.D. in Economics from Vanderbilt University.

Patrick Mabuza is a Principal Research Economist at the African Development Bank. Before joining the African Development Bank, he worked with the National Energy Regulator of South Africa as an Economist. He has also worked with the South Africa Reserved Bank, and the Development Bank of Southern Africa. He holds a PhD in Economics from the University of South Africa.

References

AfDB-Afrieximbank. (2020). Trade Finance in Africa: Trends Over the Past Decade and Opportunities Ahead. AfDB-Afrieximbank.

Auboin, M. (2009). “Restoring trade finance: what the G20 can do.” In The collapse of global trade, murky protectionism, and the crisis: Recommendations for the G20. Pages 75–80.

Baldwin, R. E. (Ed.). (2009). The great trade collapse: Causes, consequences and prospects. CEPR.

Kim, K., Beck, S., Tayag, M. C., & Latoja, M. C. (2019). 2019 Trade Finance Gaps, Growth, and JobsSurvey.

BNY Mellon (2019). Global Survey: Overcoming the Trade Finance Gap: Root Causes and Remedies. Tech. rep., Bank of New York Mellon.

Mora, J., & Powers, W. (2009). “Did trade credit problems deepen the great trade collapse?” In The great trade collapse: Causes, consequences and prospects. CEPR.

UNCTAD (2020). Economic Development in Africa Report 2020: Tackling illicit financial flows for sustainable development in Africa. UNCTAD.

World Bank (2018). The decline in access to correspondent banking services in emerging markets, impacts, and solutions. World Bank.

World Economic Forum (2016). The Global Enabling Trade Report. World Economic Forum.