This article is part of a series on the Nigerian 2023 Elections. The series is edited by Serwah Prempeh and Dr. Olumide Abimbola.

Summary

- Nearly a decade on, Nigeria is still suffering from the effects of the 2014 oil price crash

- Difficult decisions on Nigeria’s public finances have been repeatedly postponed. The next president can no longer afford that stance

- The state of Nigeria’s public finances is so dire that a new government will be able to achieve almost nothing without difficult and painful reforms

- What began as a large but manageable budget deficit in 2015 has metastasized into a runaway deficit larger than the government’s entire revenues

- Contenders for Nigeria’s presidency are making ambitious and expensive promises as part of their campaigns, but they are all silent on the elephant in the room: the country’s finances.

The hunt for unencumbered revenues

Anyone looking for them can clearly see the serious economic and political problems confronting Nigeria. The current stock of infrastructure, where usable, is unable to meet the needs of a country that carries the hopes and dreams of more than 200 million people. The country has been fighting a low-level civil war in its northeast for longer than anyone can remember. The insecurity, once confined to that part of the country, has now spread almost everywhere. The future of the country’s biggest foreign exchange earner – crude oil – is extremely uncertain in the current climate of decarbonization and a shift away from fossil fuels. Yet, while dealing with all of these issues calls for difficult decisions over the medium to long term, the more immediate problem requiring urgent action is the state of the country’s public finances. Without solving this dilemma, it will remain impossible to even begin to confront other longer-term issues.

Pick up the manifesto of any of Nigeria’s leading contenders in the country’s presidential elections in February 2023 and you will be confronted by a raft of spending promises. US$10 billion here for small- and medium-scale enterprises, a few billion there for hospitals and infrastructure all across the country. It is, of course, nothing new. Nigerian politicians often make promises they don’t intend to keep or, to be more charitable, they haven’t properly thought through the cost implications.

But this time around, there are good reasons not to give politicians a pass over their spending plans. For one thing, the dire state of the country’s finances is well known, and has been for a considerable time. If nothing else has cut through to the public, the rate of government borrowing definitely has. A story about the country’s indebtedness is guaranteed almost every day in Nigerian papers now. The effect of this borrowing is that debt servicing now consumes the entirety of the government’s revenues, as hard as that is to believe. Any new government runs the risk of entering into office only to take charge of the privilege of sending payments to Nigeria's creditors, and nothing else.

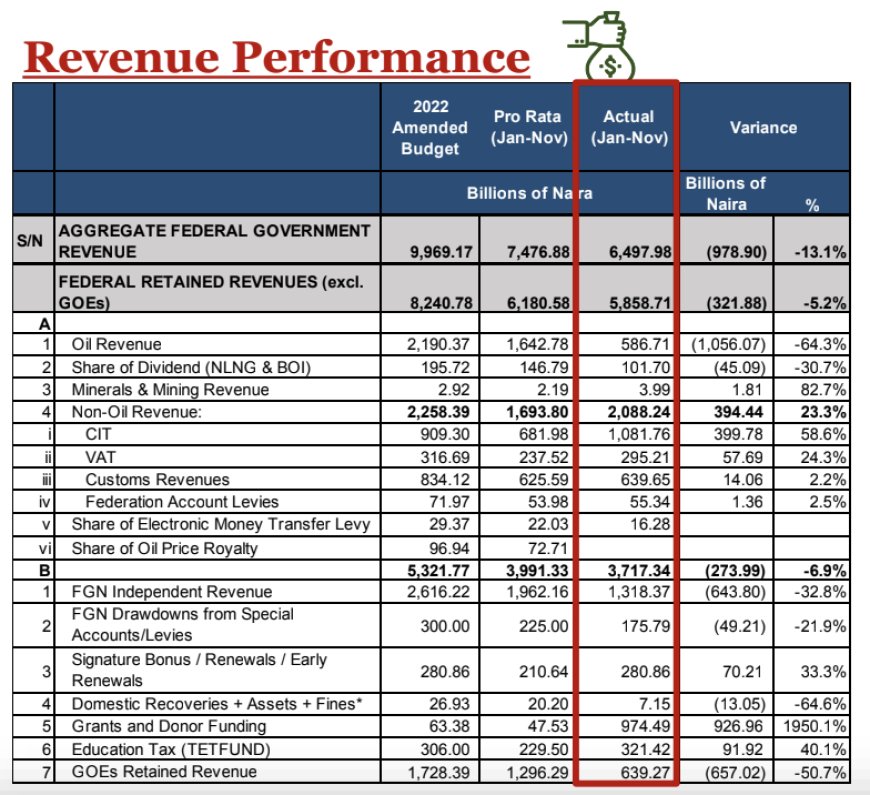

The second issue is the knock-on effect of all of the fiscal annual-budget legerdemain the government has had to perform to keep the show on the road. For as long as most people can remember, Nigeria’s budgets have always only been linked tenuously with reality. But whatever the link, it was completely severed after the oil price crash of 2014. At the time, both the outgoing People’s Democratic Party (PDP) government of Goodluck Jonathan and the incoming All Progressive Congress (APC) one of Muhammadu Buhari foresaw as temporary the precipitous drop in the price of crude oil, on which the Nigerian government has historically relied for its revenues. As such, not only was no serious attempt made to reduce government spending but the growth in spending continued apace as it had done in the previous heady half-decade when oil prices had exceeded $100/barrel. In 2015, when the current government took over, the budget planned for N4.5 trillion in expenditures (US$22.5 billion, €20.5 billion at the time), funded by estimated revenues of N3.4 trillion and borrowings to cover the N1 trillion revenue shortfall. Eight years on and the final budget of the Buhari government for 2023 has plans to spend N20.5 trillion (US$44.5 billion, €40.9 billion), funded by N9.7 trillion in estimated revenues and N10.8 trillion of borrowing to cover the revenue shortfall (see Figure 1). Even the revenue assumptions are daring given that, according to the government’s own budget performance report, January to November 2022 only yielded N6.5 trillion in actual revenues. Yet, the planned borrowing exceeds these hopeful revenues.

Figure 1: Nigerian Budget Figures for 2023

Source: Public Presentation of Approved 2023 FGN Budget - Breakdown & Highlights (Page 11)

The numbers are increasingly difficult to understand, even for experts let alone for a casual observer. What began in 2015 as a hopeful kick of the can down the road while waiting for oil prices to recover has now taken on a life of its own where, in my opinion, the government simply manufactures revenue numbers in the budget to make the document look respectable. In reality, whatever spending is planned will be spent while revenues will be replaced by more and more borrowing, increasingly – illegally – from the Central Bank via the so-called ‘Ways& Means’ funding.

All these fiscal juggling acts are approaching untenable levels, and one might say something has to give, even though Nigeria has an incredible capacity to temporarily fudge its way out of trouble. Contenders for office must provide the sorely needed answers and ideas as to how they intend to square this circle. So far, we have been handed populists' ideas around cutting ‘wasteful’ spending and ‘plugging leaks’. While a strong case can always be made for the Nigerian government hardly being the best steward of public funds, and there is always some fat to trim, a deeper look at the figures quickly shows the limits of simply cutting spending as a serious strategy to tackle the problem.

Table 1: Summary of Federal Government Finances (₦' Billion)

| Item | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 20204 | 20214 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Federally Collected Revenue | 7.444,8 | 9.551,7 | 10.262,3 | 9.276,1 | 10.755,4 |

| Oil Revenue | 4.109,7 | 5.545,8 | 5.536,7 | 4.732,5 | 4.358,3 |

| Non- Oil Revenue | 3.335,1 | 4.005,9 | 4.725,7 | 4.543,6 | 6.397,1 |

| Federation Account | 2.119,9 | 3.179,0 | 3.078,5 | 2.534,1 | 2.647,3 |

| Fed Govt Retained Revenue | 2.847,3 | 4.185,6 | 4.894,0 | 3.983,1 | 5.045,4 |

| Total Expenditure | 6.456,7 | 7.813,7 | 9.714,6 | 10.231,7 | 12.164,1 |

| Recurrent Expenditure1 | 4.780,0 | 5.675,2 | 6.997,2 | 8.188,8 | 9.145,2 |

| Transfers2 | 434,4 | 456,5 | 428,5 | 428,0 | 496,5 |

| Current Surplus(+)/Deficit(-) | -1.932,7 | -1.489,5 | -2.103,2 | -4.205,7 | -4.099,7 |

| % of GDP | -1,7 | -1,2 | -1,4 | -2,7 | -2,4 |

| Overall Surplus(+)/Deficit(-) | -3.609,4 | -3.628,1 | -4.820,6 | -6.248,6 | -7.118,7 |

| % of GDP | -3,1 | -2,8 | -3,3 | -4,0 | -4,1 |

| Nominal GDP | 114.899,2 | 129.086,9 | 145.639,1 | 154.252,3 | 173.527,7 |

| Financing: | 3.609,4 | 3.628,1 | 4.820,6 | 6.248,6 | 7.118,7 |

| Foreign (net) | 1.240,4 | 1.073,3 | 0,0 | 0,0 | 1.623,6 |

| Domestic (net) | 2.369,0 | 2.554,8 | 4.820,6 | 6.248,6 | 5.495,1 |

| Banking System (net) of which: | 1.337,6 | 0,0 | 0,0 | 0,0 | 0,0 |

| CBN | 0,0 | 0,0 | 0,0 | 0,0 | 0,0 |

| Deposit Money Banks | 1.337,6 | 0,0 | 0,0 | 0,0 | 0,0 |

| Non Bank Public | -517,2 | 668,8 | 912,8 | 2.057,5 | 2.895,5 |

| Privatization Proceed | 372,4 | 0,0 | 0,0 | 0,0 | 0,0 |

| Other Funds3 | 1.176,3 | 1.886,0 | 3.907,8 | 4.191,0 | 2.599,6 |

Source: Central Bank’s of Nigeria Public Finance Statistics report

Here we see a high-level breakdown of how the Nigerian government spends its money, albeit only available up to 2021 (the debt service numbers have deteriorated significantly in the last two years). Even the most cold-hearted fiscal consolidator will struggle to find even N1 trillion (roughly 10 percent of total spending) worth of spending to cut. Defense? The country has been at war with Boko Haram in the country’s northeast, to say nothing of criminal bandits all over the country, for well over a decade, and any drop in spending risks handing them the initiative. Indeed, the defense budget is barely sufficient to wage this war, and the country continues to rely on the kindness of strangers to plug a lot of the shortfall. Education and Health? You can double the current spending levels and still have millions of out-of-school children across the country; a problem showing no signs of a let-up. And the less said about the country’s healthcare system, the better. Suffice it to say that much of the current spending simply go towards paying salaries, something any leader will be loath to touch given the social implications of cutting government staff numbers. As for debt servicing, the government has to pay its debts, and much of the debt is now domestic anyway, meaning the government cannot force any kind of losses on its local creditors without a serious knock-on effect on the financial system and economy.

Why would anyone want the job that is dealt with such a hand as its inheritance? Having allowed the problem to fester for so long with easy short-term fixes, Nigeria is now left with nothing other than difficult choices. Contrary to what some candidates may be saying on the campaign trail, this is not something that can be fixed by the Central Bank simply printing more money. If it was, the last five years of unprecedented monetary expansion would have made a difference. The next government will have only one obvious lever to pull – the one attached to the ruinous petrol subsidies, projected to cost more than N6 trillion (approx. US$13 billion, €12 billion) in 2023 (the outgoing government has accounted for half of it running up to June 2023 in its final budget). Yet, in keeping with the theme of a government that has run out of road and given the reality of the numbers and deficit outlined above, removal of the petrol subsidies will only yield a one-time breathing space of a few months. And the removal of the subsidies, while economically sound and long overdue, will come at the risk of social unrest and even more painful inflation.

And so, we are left with one question to ask the contenders for office - where are you going to find the unencumbered revenues to fund your plans and promises? While the governing is a continuous exercise, a change of government should at least offer some relief or opportunity for a reset. It will be a tragedy if Nigeria elects a new government simply to continue from where the old one left off. All remaining options are hard. They require deep-rooted reforms that unlock the value in Nigeria’s human capital and begin the difficult task of confronting a future with no oil revenues. What will Nigeria offer the world when it no longer has oil? Just a constant stream of emigrants? Or can it provide products and services of real value created in the country, allowing it to pay its way in the world? What will be the country’s place in the world when it’s no longer ‘strategically important’ as a supplier of crude oil? A place where insurgents and bandits have the keys to any city they want or a place heaving with millions of energetic Nigerians with avenues to unleash their creativity and a people who don’t accept that they are beaten.

Every election often feels like the most important in a country’s history. But for once, this one merits the label. Nigeria is at a crossroads, and a failure to take on these challenges risks sending the country into a deeper hole from which it might take a generation to dig itself out. The problems are difficult, but it is not beyond human ingenuity to get a grip on them and begin to turn things around.

One can only hope that those currently jostling for power are thinking about this as seriously and soberly as the moment demands.

- Includes interest payments on debt service, other transfers and extra-budgetary items.

- Includes capital repayments on debt service, other transfers and net lending

- Includes Public, Special and Trust Funds, Treasury Clearance Funds, excess reserves, FG's contribution to the External Creditors' Fund, etc. Minus (-) denotes increase; Plus (+) denotes decrease.

- Provisional

About the Author

Feyi Fawehinmi is a qualified accountant and has worked in the financial services industry for nearly two decades. He has written several articles in Nigerian and global publications including the BCC, Quartz Africa, Guardian Newspapers Nigeria and others. He is the co-author of a well received book on 19th Century Nigeria titled Formation: The Making of Nigeria from Jihad to Amalgamation. He lives in the UK with his family.