Summary

- Several MoUs and agreements related to the Lobito Corridor have recently been signed. The parties involved are diverse, including the EU, the US, Angola, the DRC, Zambia, AfDB, and AFC, as well as a consortium comprising Trafigura, Mota-Engil, and Vecturis.

- The major interest in the Lobito Corridor is to use it as a route for transporting critical raw materials (CRMs), strategic minerals, and products of the EV battery value chain, from the DRC and Zambia to the EU and the US.

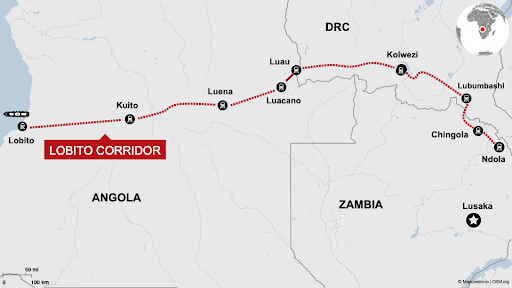

- The Lobito Corridor traverses 1,300 km east through Angola from the Atlantic Ocean coast to the border with the DRC and within easy reach of the Zambian border. Its operation has been concessioned to private sector players.

- The challenges associated with the viability of the Corridor relate to the fact that the targeted materials are mostly already locked in by China, and that the Asians are leaders in EV technology.

- The EU and the US will need to implement holistic strategies to respond to these challenges.

Introduction

The Lobito Corridor consists of a 1,300 km railway line traversing Angola from the Atlantic Ocean to the country’s borders with the DRC and Zambia. The Corridor has seen a resurgence in interest in recent months, as evidenced by the signing of MoUs and agreements, most of which concern the development of the Corridor and activities related to green and clean energy technologies, in particular EV battery value chain products. However, while the impetus for this attention is understandable, there are factors and dynamics which indicate that the viability of the Corridor could be brought into question. The EU and the US will need to remain cognisant of these adverse dynamics and put appropriate measures in place to address them.

The Lobito Corridor

As mentioned above, the Lobito Corridor is conceptualized around a 1,300 km stretch of railway line from the port of Lobito, on the Angolan Atlantic Ocean coast, to the town of Luau on the north-eastern border of Angola with the DRC and within easy reach of north-western Zambia. The railway line extends a further 400 km into the DRC to the mining town of Kolwezi. The Corridor has recently been concessioned to a consortium comprising the commodity trader Trafigura (49.5%), and European partners Mota-Engil (49.5%) – construction, and Vecturis (1%) – railway operations.

While the consortium has targets for the movement of cargo on the railway line and through the dedicated port terminal, it is envisaged that the surge in demand for critical minerals, particularly from the EU and the US, will anyway drive increased volumes of traffic onto the railway line.

MoUs and Agreements

Several MoUs and agreements focusing directly or indirectly on the development of the Lobito Corridor have recently been signed. Common among them is a sharp focus on the use of the Corridor as a route along which strategic minerals, CRMs, and EV battery value chain products can be transported to the EU and the US.

For example, an MoU signed by the EU, the US, the DRC, Zambia, Angola, the African Development Bank (AfDB), and the Africa Finance Corporation (AFC) describes an extension of the railway line to Zambia. Meanwhile the Lobito Corridor Transit Transport Facilitation Agency Agreement (LCTTFA) – signed by the governments of Angola, the DRC, and Zambia – will accelerate domestic and cross-border trade along the Corridor and foster the participation of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in value chains.

MoUs and Agreements Related to Lobito Corridor

EU, US, DRC, Angola, Zambia, AfDB, AFC MoU – Development of LC

Angola, DRC, Zambia Agreement (LCTTFA) – Trade and Development

EU, DRC MoU – Critical Minerals and Value Chain Development

EU, Zambia MoU – Strategic Minerals and Value Chain Development

US, DRC, Zambia MoU – Support EV battery value chain

DRC, Zambia Agreement – EV battery value chain

Angola, Trafigura, Mota-Engil, Ventricles – Concession agreement

More recently, the EU has also signed specific MoUs with the DRC and Zambia. The latter, titled “Partnership on sustainable raw materials value chains”, outlines how the EU is seeking to secure the supply of strategic minerals and CRMs.

That the unprecedented agreement between the DRC and Zambia based on the development of the EV battery value chain and clean energy has spurred the signing of other MoUs and agreements with relation to the Lobito Corridor is not farfetched. To this effect, the EU in its MoU with Zambia seeks that the partners are committed to local value-addition, and to respecting each other’s right to extend the raw material and net-zero-technologies value chains within their countries, among other objectives.

In addition, the US has signed a tri-lateral MoU with both the DRC and Zambia supporting the development of a value chain in the Electric Vehicle (EV) battery sector. In this case, the US is very deliberate that it is about supporting the development of a value chain in the EV battery sector and commits to promoting the Zambia and DRC EV Battery initiative within the US private and investment sectors.

Why now?

The International Energy Agency (IEA) has estimated that between 2020 and 2040, demand for nickel and cobalt will increase by twenty times, for graphite twenty-five times, and for lithium more than forty times. This projected surge in demand for CRMs has fuelled great interest in the Lobito Corridor, and with it an inevitable scramble for access. The DRC, as the world’s largest producer of cobalt (estimates are consistently around 70% of global production), has found itself at the epicenter of this scramble, as has, by association, Zambia.

The EU and the US are among those vying for a place at the table, indicating that they will explore the development of green power projects and support investment in CRMs and clean energy supply chains along the Corridor. The awarding of the Lobito Corridor operation concession to the above-mentioned three-member consortium (comprising two European partners) has also added impetus to the renewed focus on the Corridor from the EU perspective.

Challenges to the Lobito Corridor Proposition

There are several challenges to basing the Lobito Corridor development on transporting CRMs and products of the EV battery value chain to the EU and the US. Firstly, not only are the Chinese ubiquitously present on the African continent, but China is already far ahead in building supply chains for cobalt, lithium, and several other essential metals and minerals. And what is more, China is moving to take over the running of the TAZARA railway line, which runs from central Zambia to the port of Dar es Salaam on the Indian Ocean, as a way of ensuring effective transportation of materials and minerals from the DRC and Zambia. It is also not insignificant that China signed MoUs with most African countries a decade ago. The fruit of some of these are infrastructure developments that have already been rolled out on the continent through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

The other challenge is that the EV battery value chain is not only complex, with almost 300 players already involved and regionalization being a big factor, but that the EU and the US are not currently leaders in EV technology. It is reported that almost 90% of cell component manufacturing, the most significant step in the battery value chain – 30% of players in the six-stage value chain are concentrated here – is undertaken in Asia. Indeed, two major European car manufacturers have recently been reported to have acquired stakes in Chinese EV manufacturers to gain access to their EV technology. In addition, the largest Chinese EV manufacturer, BYD, has surpassed Tesla in terms of EV production as per the Q4 2023 figures. Both TESLA and BYD are also major players in EV battery technology.

What Should the EU and the US Do Differently?

Given the challenges that the development of the Lobito Corridor is likely to face, and that the EU and the US may have limited access to CRMs and other strategic materials through this route, these parties will need to look beyond merely securing the supply of CRMs and other strategic minerals to transport on the Corridor. Instead, they need to invest in the industrialization of the African continent across the board. This medium- to long-term strategy should be to build future markets for their iphones, BMWs, etc.

Indeed, “Towards a Comprehensive Strategy with Africa”, the European Critical Raw Materials Act, and the emphasis on sustainability and circularity, need to go beyond developing a responsible raw materials sector, as important as that is. They need to consider advancing Africa’s overall economic development. This not only makes sense from the point of view of building markets of the future and possibly countering China’s presence - if that is part of the objectives - but from the simple question of population dynamics: Even if the EU wanted to set up EV-driven industries within its own borders, it would lack the manpower to do so.

Source: The China-Global South Project (CGSP)

Conclusion

The reality of the Lobito Corridor development is that it may be coming too late in the day. This is certainly true as far as transporting CRMs to the EU and the US is concerned, since most of the supply has already been locked in by China. What is more, there is a proposed route, shorter by some 500 km, to the East between Lubumbashi and Dar Es Salaam. This is likely to put the viability of the Lobito Corridor even more in question, in addition to the Chinese taking over the running of TAZARA railway line.

With the EU and the US lagging in terms of EV technology, it is very likely that the DRC and Zambia will end up looking to the East for the capacity and capability building of EV battery value chains. The EU and the US therefore need to look beyond the Lobito Corridor initiative and consider a more holistic approach, one which engages with the DRC and Zambia as nodes to spur industrial development across Africa.

About the Author

E. D. Wala Chabala

Dr. E. D. Wala Chabala is an Independent Economic Policy and Strategy Consultant and MBA Lecturer. He is a former Management Consultant at McKinsey & Company and a former Business Executive in a FTSE-100 Financial Services Company. He has also formerly been Chief Executive Officer of the Securities and Exchange Commission of Zambia.