This article is part of a series of special thought pieces that APRI published in partnership with the African Climate Foundation in the run up to COP27 in Egypt. The series is titled “What does the Just Transition mean for Africa”.

Summary

- The current global decarbonisation agenda creates many socio-economic challenges for Africa that require the international community’s attention.

- Fossil fuels currently represent around 40% of African exports. As the global demand for green energy sources increases in comparison to fossil fuel energy, African fossil-producing countries will take the hit.

- The African continent is rich with mineral resources that are pivotal for the production of low-carbon technologies and infrastructure. African economies can leverage these resources to diversify their economic development and achieve a just green energy transition.

- Regional cooperation through an African Green deal can considerably maximise the broader socio-economic benefits of low-carbon transitions on the continent.

- African stakeholders should consider designing an African green deal that positions renewables as a lever of economic diversification and industrialisation and supports their growth and climate resilience agenda.

Background

Africa has often been perceived as a source of raw materials to fuel the global energy transition, with little attention on what is needed to maximise the broader socio-economic benefits of low carbon transitions in this continent. In the context of the COP27 being hosted on the African continent and in the optic of raising attention to African perspectives on decarbonisation, this thought piece highlights how African governments can tackle energy transitions in a way that supports the much-needed industrial development and economic diversification across the continent, rather than reinforcing existing commodity dependencies. I argue that the status quo will not help African economies overcome the seriously devastating economic effects of climate change nor seize the opportunities that arise from global decarbonisation, which calls for a major rethinking of policy strategies – including in terms of regional cooperation and negotiation with international partners.

Both climate change & the global decarbonisation agenda can exacerbate trade vulnerabilities in Africa

Climate change has already resulted in considerable economic damage on the African continent. In 2020 alone, African nations suffered economic losses of approximately US$38 billion because of climate change effects.[1] Such losses are expected to increase in the future due to shifting precipitation patterns, rising temperatures, and more frequent extreme meteorological events (such as floods, droughts, and hurricanes), which damage infrastructure, reduce revenues, and generate productivity losses, especially in the agriculture sector, which generates the most jobs in Africa (accounting for nearly half of total employment) and which many countries rely on to ensure their food security.[2] This vulnerability affects women disproportionately since the agriculture sector is female dominated.[3]

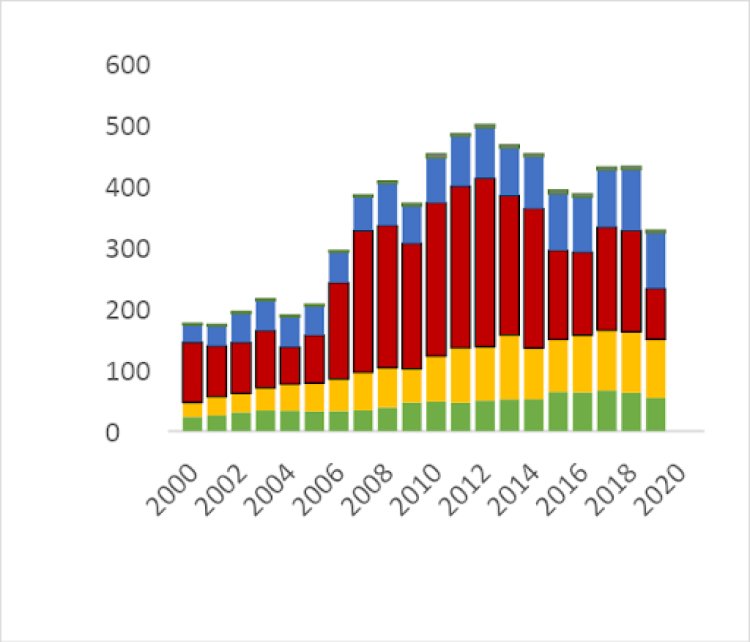

Africa is in fact the most commodity-dependent region in the world.[4] Africa’s dependence on primary commodities (namely agriculture, mining, and fossil fuels, see Figure 1) makes the continent particularly vulnerable not only to the effects of climate change but also to the global decarbonisation agenda. Indeed, the global push towards decarbonisation brings about both challenges and opportunities for the region’s economies. On the one hand, several fossil fuels producing economies (such as Algeria, Angola, Chad, and Nigeria) are facing uncertainty as fossil fuel demand is expected to drop in the medium to long term, likely causing the loss of considerable amounts of public revenues and jobs. Overall, fossil fuels currently represent around 40% of African exports. In the context of a low-carbon future, fossil-fuel-dependent countries will be increasingly vulnerable to the risks of stranded assets, in addition to the already serious effects of price volatility. Beyond only improving access to energy, these countries will need to undergo a process of economic diversification to build resilient and productive economies as demand for fossil fuels falls.

Figure 1.a. Evolution of exports across Africa, by sector, 2000-2019

Figure 1.b. Composition of exports, by African subregion, 2019

On the other hand, several African countries are poised to benefit from their large endowment of minerals (such as cobalt, lithium, copper, manganese, and platinum) that are essential inputs for low carbon technologies, such as electric batteries and wind turbines. For instance, the Democratic Republic of Congo is one of the world’s largest cobalt producers, Rwanda has become the world’s largest exporter of tantalum, while South Africa is the world’s largest producer of platinum and manganese. However, the long-term outlook for these minerals is still dominated by uncertainty and risks of technological disruption, given the serious R&D efforts globally to generate alternative technologies that rely on substitute materials (such as phosphate-based or hydrogen-based batteries to replace lithium-ion batteries or substitutes to cobalt in electronics).[5]

African firms will also have to adapt to- and anticipate- sustainability trade standards and shifting consumption patterns in key markets, such as the USA or the EU. For instance, the European Commission’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) can have a considerably negative impact on African trade and the ability to export goods to the EU. Even if the CBAM will only apply to specific sectors between 2023 and 2026, many of those sectors (cement; iron and steel; aluminium; fertilisers; electricity) are amongst the few non-resource manufactured goods that are already exported – or have high potential for international competitiveness in several African countries. Greening those sectors will therefore be important to gain (or retain) market accesses in key consumer markets.

Fortunately, some African countries, such as Egypt, Ethiopia, Kenya, Algeria, and Morocco are showing increasingly concrete ambitions to deploy clean energies, along with a growing interest in integrating global value chains in the renewable energy sector, but there is still a lot more to be done to reap the full potential that clean transitions can provide on the continent.

Renewables as a lever of economic diversification and industrialisation

Renewable energy development in Africa is an important agenda for various reasons. Firstly, close to 600 million were still without access to electricity in 2018.[6] This situation reinforces socio-economic inequalities and impedes progress in widening access to basic health services, education, and modern machinery and technology – thus, ultimately, to socio-economic opportunities.[7]

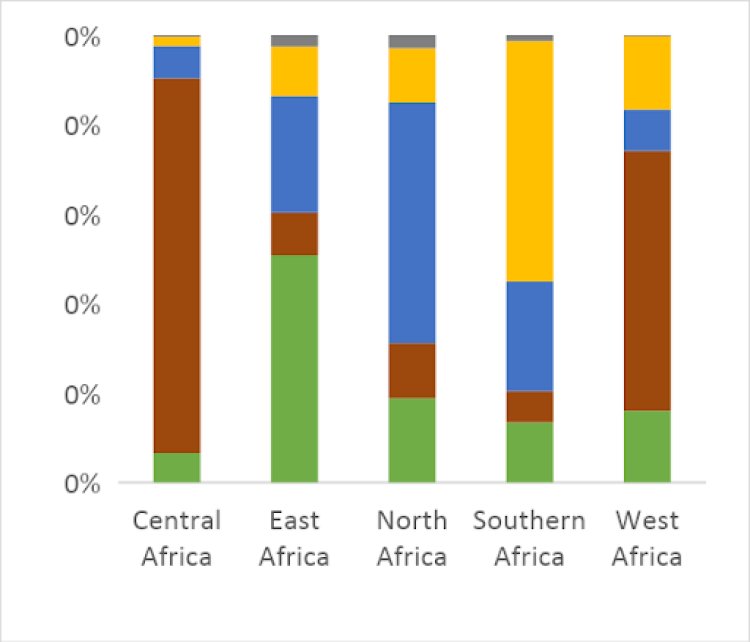

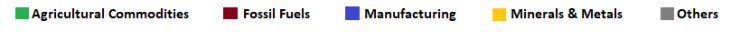

Secondly, in light of global energy trends, renewables can play a key role in offsetting job losses in the fossil fuel sector. Investing in energy transition technologies creates close to three times more jobs than fossil fuels do for every million dollars of spending.[8] According to estimates from the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), job gains in the renewable energy sector in Africa would far outweigh the loss of 1.07 million jobs in the fossil fuel and nuclear sectors.[9] However, to date, the African continent has only captured about 2.8% of jobs created in the renewable energy sector globally (around 330,000 out of 12 million jobs created globally), as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Global (uneven) distribution of jobs created in renewable energies

Thirdly, beyond energy objectives, renewables expansion can be leveraged as an engine of industrial development, which is highly relevant given that manufacturing is key to structural transformation and sustained economic development.[10] Despite significant progress in the 2000s, a large majority of African countries saw their manufacturing value added (MVA) per capita rates stagnate or even decrease (as in Southern Africa) since 2014. Africa’s average (MVA) per capita (of about USD 207) is now about eight times lower than the world average (USD 1 683) because Africa’s economic growth and employment generation have relied heavily on low-value-added sectors, such as raw commodity exports (fossil fuels, mining, and agriculture).[11] To break the pattern of trade and commodity dependence in the context of low carbon technologies, African countries can attempt to integrate higher value-added segments of renewable energy value chains, rather than sticking to the provision of raw materials (such as copper or lithium) and supply, installation, and maintenance activities. So far, Africa is registering a modest 0.7% of the patents filled in renewable energy technologies in 2021 and is currently capturing a negligible share of global low carbon technology exports, in contrast to countries such as China, South Korea, Malaysia, Germany, or even the USA – though to a lesser extent (see figure 3).

To move forward with the expansion of manufacturing capacity around renewable energy, establishing clearer roadmaps and long-term energy planning will be key for gaining investor trust in local and regional renewables supply chains. African countries could also take advantage of cheap and clean energy sources, not only to decarbonise electricity generation, but also as feedstock to develop competitive value-added low carbon services and industries, such as green hydrogen production, low carbon manufacturing, and low carbon technology services. Such use of renewable energy to promote economic diversification will be key in creating green jobs and offset the expected job losses in the fossil fuel sector. Furthermore, as rightfully pointed out by Carlos Lopes, African policymakers would show a lot more interest towards renewables if those investments were designed to develop corridors of green industrialisation in their countries.[12]

Figure 3: Global distribution of selected low carbon technology exports by country in 2020

The role of industrial policy for a renewables-based industrialisation

In a 21st century context of global decarbonisation and the fight against climate change, the exact conditions that allowed the East Asian miracle might not be replicable anymore, and the much-needed structural transformation of African economies will benefit from an emphasis on low carbon solutions and the so-called “industries without smokestacks”.[13]

From that perspective, there is a lot that African governments can do at the national level to localise the industrial benefits that arise from energy transitions. Such policies would go beyond mere renewable energy adoption and deployment measures but would also entail the promotion of value-added activities that feed into renewable energy value chains. For instance, possible policy actions include green industrial policies,[14] such as appropriate local content incentives, business incubation initiatives, R&D support, the promotion of low carbon industrial clusters, as well as green skills development programmes to train the workforce required for decarbonised industries and reskill energy sector workers; adapted fiscal policies to attract investments to nurture start-up and industrial ecosystems around low carbon services; circular economy policies[15] to help countries and communities manage scarce resources, and trade waste material to reduce the lifecycle of emissions in various industries, thereby improving both resource efficiency and productivity.

Once a taboo topic associated with inefficiencies, abusive interventionism, and elite capture, industrial policies have been increasingly acknowledged in recent years as necessary ingredients of economic diversification. A strong body of evidence suggests that market forces are not sufficient to stimulate economic diversification and that the acquisition of new comparative advantages across several now-diversified and industrialised countries has benefited to a large extent from government interventions.[16] Furthermore, industrial policies are now experiencing a ‘green’ renaissance in economic policy across the globe, given the increasing acknowledgement (even by the Biden administration in the United States earlier this year) that they are central to driving the structural transformation towards a more sustainable economic system.[17]

Green industrial policies therefore deserve much more emphasis in African countries aiming to reap the industrial opportunities associated with energy transitions. The African continent features various experiments with the design and implementation of industrial policies around the energy sector (though mostly in the oil and gas sector, and mostly consisting of local content initiatives).[18] The most ambitious industrial policy efforts towards adding value to the renewable energy sector can be found in South Africa, where the Renewable Energy Independent Power Producer Procurement Programme (REIPPPP) was launched in 2011 to allow the state-owned utility Eskom to procure electricity from private producers through a competitive tendering process for which selection criteria include local content and local job creation.[19]

Meanwhile, other countries such as Algeria and Nigeria have also taken some steps towards supporting local capabilities around renewables. For instance, besides local content objectives in solar plant tenders, Algeria’s Renewable Energy Development Centre (CDER) was created in the 1980s to conduct R&D, develop patents, and offer testing services for local manufacturers in the renewable energy sector. Nevertheless, considerably more – and better - efforts are required to achieve economies of scale and for renewable-energy related equipment to become sufficiently competitive to eventually contribute to these countries’ export baskets. One of the main challenges remains the implementation of appropriate institutional governance to ensure the success of industrial policy, including clarity and transparency relating to the criteria used to support some activities/sectors over others, performance requirements, evaluation and monitoring capacity, and credible long-term objectives.

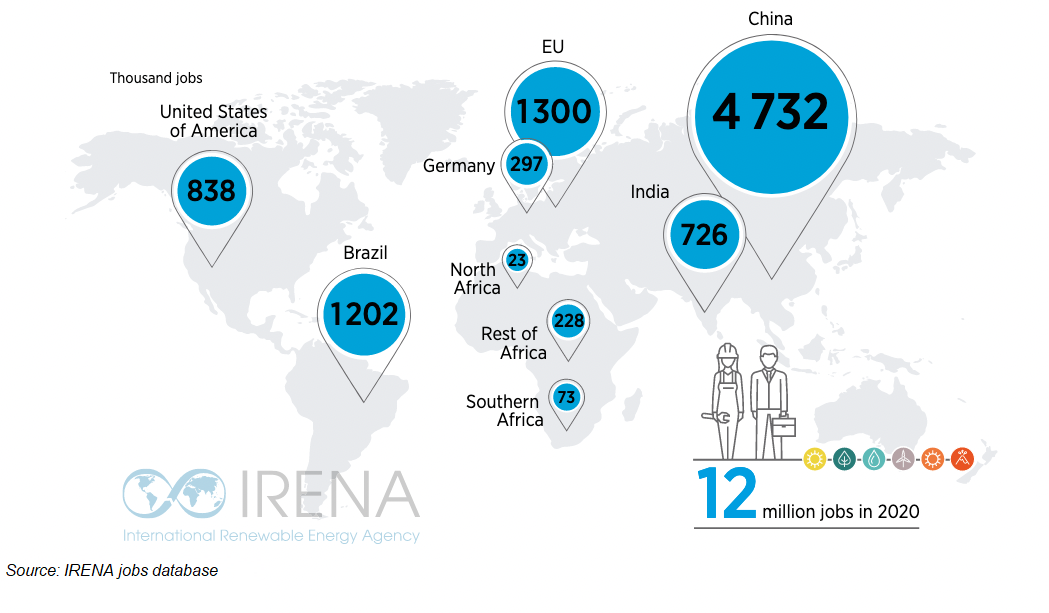

Why regional coordination matters

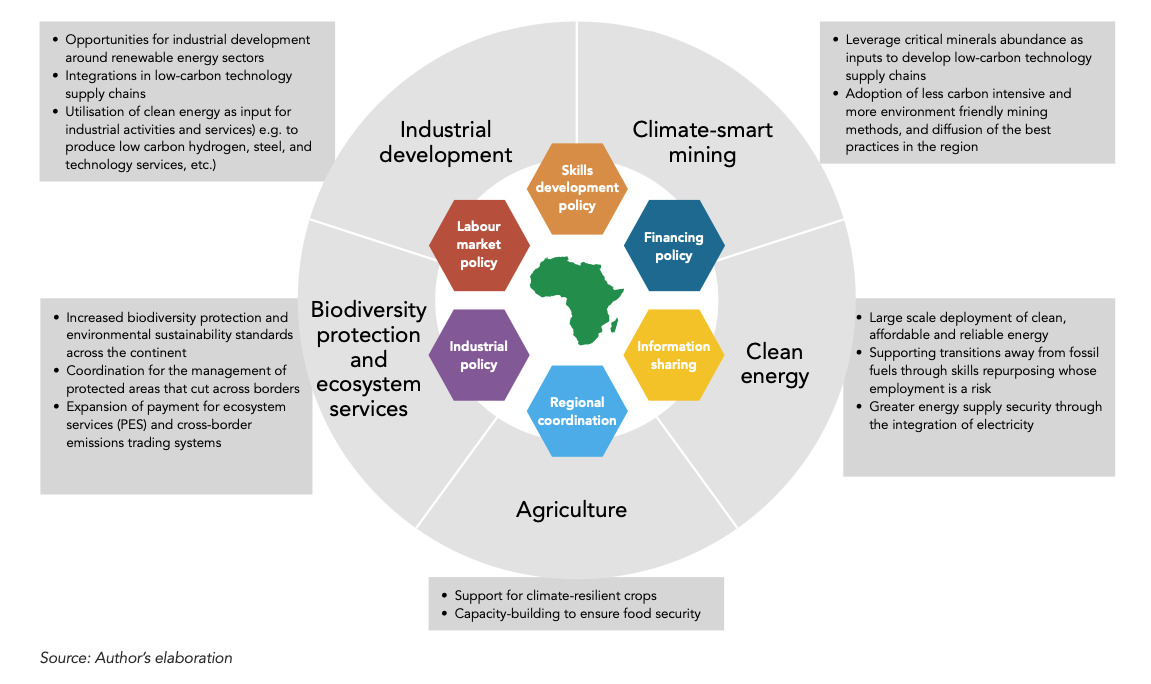

Notwithstanding what individual governments can do at the national level, there is a limit to how much can be achieved in Africa without regional cooperation. Each African country has different comparative strengths, from a variety of (complementary) critical minerals that are spread across the region (e.g. DRC, South Africa, and Zambia), to manufacturing capacity (e.g. Morocco and Egypt) and renewable energy potential (e.g. Algeria, Namibia, and Sudan), as well as proximity to important trade routes (e.g. Djibouti). All these complementary assets can be part of a carefully designed plan –perhaps an African green deal? - to develop an efficient regional industrial ecosystem around low carbon technologies, thereby generating considerable positive impacts across a range of sectors, including energy, climate-resilient agriculture, low carbon manufacturing, carbon emissions trading, and the bioeconomy.

Figure 4: Multilevel sectoral impact of regionally coordinated green policy action in Africa

A Green New Deal is essentially a comprehensive policy package that aims to bring together the objectives of achieving climate goals (such as reduced GHG emissions); fostering economic development and job creation, and guaranteeing equity and welfare for society as a whole. To date, green deals have been proposed and discussed in various geographies and contexts but have remained principally framed in the context of advanced economies, with discussions focusing on strategies to develop the productive and innovative capabilities of domestic firms in those countries. Meanwhile, the African continent has often been perceived as a source of raw materials to fuel the global energy transition, with little attention on what is needed to maximise the broader socio-economic benefits of low carbon transitions in this continent.

Therefore, much more policy, academic, business, and civil society attention need to be devoted to improving our understanding of the opportunities, obstacles, and regional cooperation processes (including trade coordination, financing, political cooperation, and cross-border infrastructure) that are needed to unlock the potential of an African green deal as a lever of socio-economic development. The road to a regionally coordinated green economic transformation plan in Africa is paved with challenges, especially in terms of financing and political alignment, but surmounting such challenges is not impossible and is perhaps even necessary given the significant opportunities and challenges for the economic future of the region.

Endnotes

1. WMO (World Meteorological Organization (2021), State of the Climate in Africa 2020, World Meteorological Organization, Geneva

2. IRENA (2022). Renewable Energy Market Analysis: Africa and its Regions. Abu Dhabi: International Renewable Energy Agency.

3. ILO (2020), Report on Employment in Africa (Re-Africa), International Labour Organization, Geneva.

4. UNCTAD (2019) State of Commodity Dependence, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, Geneva. UNCTAD (2019) considers a country to be commodity dependent when commodities represent more than 60% of its total merchandise exports in value terms.

5. Manley, D., Heller, P. R., & Davis, W. (2022). No Time to Waste: Governing Cobalt Amid the Energy Transition. London: Natural Resource Governance Institute.

6. IEA, IRENA, UNSD (United Nations Statistics Division), World Bank and WHO (World Health Organization) (2021), Tracking SDG 7: The Energy Progress Report, World Bank, Washington, DC.

7. IRENA (2022). op. cit.

8. Garrett-Peltier, H. (2017), Green versus brown: Comparing the employment impacts of energy efficiency, renewable energy, and fossil fuels using an input-output model, Economic Modelling, Vol. 61, February, pages 439-447.

9. IRENA (2022). op. cit.

10. Kaldor, N. (1967). Strategic Factors in Economic Development, Ithaca: New York State School of Industrial and Labor Relations, Cornell University; Chang, H.-J. (1994) The Political Economy of Industrial Policy. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan; United Nations Industrial Development Organization (2020). Industrialization as the Driver of Sustained Prosperity. Vienna: UNIDO

11. ILO, op. cit.

12. Lopes, C. (2022). “Africa needs to stick to renewables despite the temptation of gas”. The Africa Report. Accessible at: https://www.theafricareport.com/a-message-from/africanclimatechange/the-africa-climate-conversation/africa-needs-to-stick-to-renewables-despite-the-temptation-of-gas/

13. Newfarmer, R., Page, J., & Tarp, F. (2019). Industries without smokestacks: Industrialization in Africa reconsidered. Oxford University Press.

14. Anzolin, G., & Lebdioui, A. (2021). Three dimensions of green industrial policy in the context of climate change and sustainable development. The European Journal of Development Research, 33(2), 371-405.

15. Albaladejo, M.; Mulder, N.; Mirazo, P.; and Jauregi, I. (2021) The Circular Economy: From waste to resource through international trade. UNIDO Industrial Analytics Platform. July. Accessible at: https://iap.unido.org/articles/circular-economy-waste-resource-through-international-trade

16. Cherif, R., & Hasanov, F. (2019). The return of the policy that shall not be named: Principles of industrial policy. International Monetary Fund; Lebdioui, A. (2019) Chile's export diversification since 1960: A free market miracle or mirage?. Development and Change, 50(6), 1624-1663; Mazzucato, M. (2016). From market fixing to market-creating: a new framework for innovation policy. Industry and Innovation, 23(2), 140-156.

17. see Anzolin and Lebdioui, op cit; Hallegatte, S., Fay, M., and Vogt-Schilb, A. (2013), Green Industrial Policy: When and How, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 6677. Washington, DC: World Bank.; Naudé, W. (2011) Climate Change and Industrial Policy, Sustainability, Vol. 3, pp. 1003-1021.; Rodrik D. (2014), “Green Industrial Policy”, Oxford Review of Economic Policy, Vol. 30, Issue (3), pp.469–491.

18. IRENA (2022), op cit.

19. Eberhard, A. and Naude, R. (2017), The South African Renewable Energy IPP Procurement Programme: Review, Lessons Learned & Proposals to Reduce Transaction Costs, Graduate School of Business, University of Cape Town.

About the Author

Amir Lebdioui is an Algerian Development Economist and Lecturer in the Political Economy of Development at SOAS, University of London. Previously, Amir led the Canning House Research Forum based at the London School of Economics. His research expertise lies in the economic development and diversification of resource-dependent nations, resource revenue management, low carbon innovation and industrialisation in the context of climate change. His work has been published in top tier academic journals including World Development, Development and Change, the Journal of Technology Transfer, and the Review of International Political Economy. Amir also regularly advises governments, international institutions and think tanks on industrial policy and sustainable economic strategies more broadly. He holds a PhD in Development Studies from the University of Cambridge.