Investment inflows over the last twenty years introduced a steep change in the stock of foreign direct investment (FDI) in West Africa from an estimated US$33 billion in 2000 to US$200 billion in 2019, according to United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) estimates. China has played its part in this transformation. However, in the conversation about economics and geopolitical influence in the region, there is a tendency to over-emphasise China at the expense of a full appreciation of three things: (a) the full cast and activities of other foreign actors, including entities from the European Union member states, (b) local interests and agency, and (c) the relationship between these two.

The full cast of characters

Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) countries received FDI inflows of approximately US$10 billion in 20191, compared to only US$2 billion in 2001. Burkina Faso, Côte d'Ivoire, Ghana, and Senegal have been standout beneficiaries—they accounted for around 20% of total regional FDI inflow at the start of the 2000s. But that figure is more like 45% today. Signature projects underpinning these activity streams include gold mining in Burkina Faso, hydrocarbons and other extractives in Ghana and Senegal, and in Côte d'Ivoire, a broad schema of financial services, extractives, and construction industry projects, and to a lesser extent manufacturing.

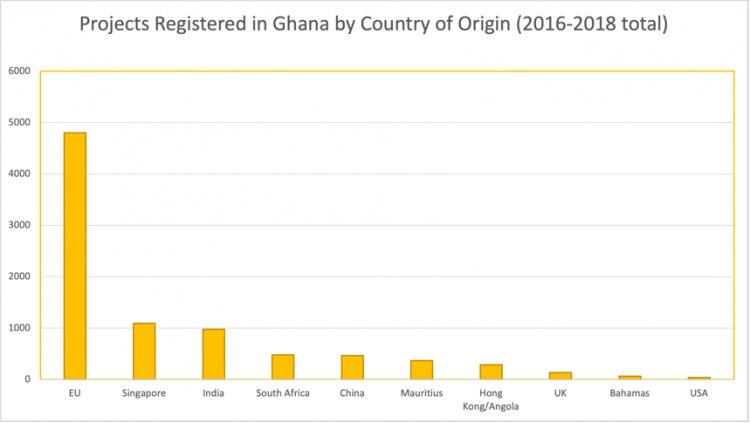

While reducing Africa to a theatre for competition between world powers is of dubious value to Africa and other entities operating in the region, we should note that China does not predominate as the home country of these new MNCs. Instead, as the Ghana Investment Promotion Centre (GIPC) graph suggests, EU-origin projects continue to play an active role2, and China is joined by an array of other South-South investors like India and South Africa. As such, even if we accept the adversarial logic that so often underpins the conversation, rather than focussing on China's offerings and possible shortcomings, much might be gained by examining how well EU-origin investment activity meets the core interests and expectations of their African counterparties and stakeholders.

Source: GIPC data available at https://data.gov.gh. Author analysis. Licence: CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0

This is even more true because there are underexploited areas that are of comparative advantage to Europe. These, when harnessed, can rake in more and 'better' FDI, discussed below.

Areas of advantage

Given West Africa's developmental requirements, insufficient domestic capital, and the concentration of FDI inflows, it should not be surprising when public- and private-sector decision-makers in these jurisdictions seek to cement novel foreign partnerships. And in that endeavour, companies from the southern hemisphere benefit from similarities in bureaucracy, consumption patterns and pricing dynamics, together with home government support that has been difficult for Western entities to reproduce.

Nevertheless, EU member states' non-extractive industry private sectors are positioned to participate in the desired FDI increase and diversification. They can take advantage of historical ties, geographic proximity, and, perhaps more importantly, major advantages of European capital markets, such as scale, liquidity, and regulatory development (including their early movement on sustainable finance). That said, if making funds available for European companies investing or seeking to invest in Africa is an agreed objective3, then the current modus operandi for risk assessment is at times an impediment.

Political risk, risks to integrity and reputational risk are not myths. They are real. However, getting market-based financing from Europe to where it needs to go in Africa is made more difficult by certain inefficiencies. Among them is a box-ticking approach to due diligence on African customers or counterparties; and information blocks that contribute to imbalances of perceived versus actual risk.

Bringing expectations into alignment

As stated, the extractive industries have accounted for a large proportion of recent FDI inflows. These are not labour-intensive projects, but they affect employment dynamics locally via direct hires. They do happen via training programmes and contracting of locally held service companies, inter alia. The weaker the relationship between FDI projects and private consumption in their immediate environs, the greater the risk of hostile regulatory action, strained communal relations or other political risk events over the long-term4. And to the extent that MNCs address these local interests, they raise the desirability of partners from their particular home country over and above that of competitors from other countries; and the converse is true as well. In that light, interpreting local content requirements by the spirit rather than letter (alone) is a potential source of long-term advantage.

Similarly, liberal economic orthodoxies are shifting around the world, including in West African markets. At the G7 meeting on 4 June, the German, French, Italian and Spanish finance ministers issued a joint statement: 'It is urgent to put in place an international tax system that is both efficient and fair … Multinationals are able to avoid corporate taxes by shifting profits offshore. That is not something the public will continue to accept. Tax dumping cannot be an option for Europe, nor can it be for the rest of the world.' The statement echoes long-held concerns on domestic revenue mobilisation expressed by African policymakers. Repatriation of profits is legitimate, but there is a renewed strategic imperative to prevent any 'short-changing' of the state.

Conclusion

Rather than seeking to reproduce other countries' advantage or compete with the same, the quantity and quality of EU-Africa investment might be better served by (a) furthering the alignment of MNC-African expectations on local content and revenue mobilisation, and (b) orientating policy to address lacunae in EU-Africa capital market cohesion, for example ensuring regulations incentivise investor risk functions, to get beyond a box-ticking approach that can miss real risks and kill real projects.

Endnotes

- Down from a high of USD18 billion in 2011. The drop off in Guinea, Nigeria has significant explanatory power.

- The Netherlands has been the largest EU contributor in each of the three years, accounting for 80% or more of EU country origin projects recorded by the GIPC. France has been in second position in each year.

- And the same for African companies wanting to raise finance in Europe.

- Eventually, the Senegalese, Ghanaian, Ivorian median voter will have her day: https://econ243.academic.wlu.edu/2017/01/30/the-median-voter-theorem/

About the author

Nana Adu Ampofo is an Africa risk specialist and an APRI Non-Resident Fellow. For over 15 years, he has assisted private and public sector clients in Sub-Saharan Africa to identify, differentiate and navigate perceived and substantive risks across the region.