Highlights

- The Africa Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) is estimated to generate USD 3.4 trillion in Gross Domestic Product, increase real incomes by 7 percent, increase trade by up to USD 70 billion and lift more than 100 million people out of poverty by 2040. Most gains will be generated by the manufacturing and services sector.

- Eastern and Southern Africa have better capacities in labour, finance, technology and infrastructure to manufacture value-added goods than their counterparts in Central and Western Africa. Countries and regions with less capacity should be supported to take full advantage of the AfCFTA. They would benefit from financial and technical assistance towards localising the agreement and building competitive value chains.

- Relative political stability needs to be assured to support the private sector and multilateral investment in cross border trade-enabling infrastructure. Leadership from the African Union and regional bodies such as the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and East African Community (EAC) are essential to ensure that changes in governments are constitutional and can support predictable policy environments for localising the AfCFTA

- Support from external actors such as the European Union and other partners of Africa is necessary in the short term, but African governments must tap into local capital markets, sovereign wealth funds, potential gains from curbing illicit financial flows, and the imposition of mandated levies to support the financing of initiatives under AfCFTA.

Issues that require urgent consideration

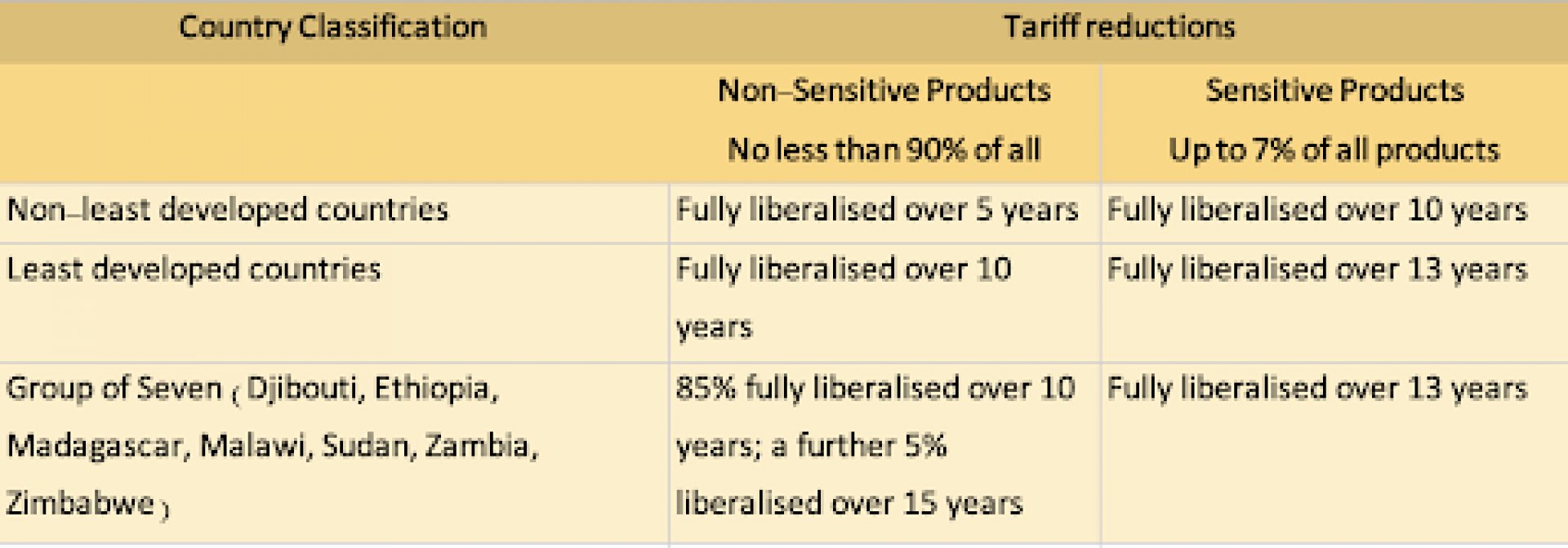

The AfCFTA aims to create an integrated market through seven core action clusters that guide its implementation. These are geared towards export diversification and the development of manufacturing and industrial value chains by member countries. These action clusters coalesce around tariff reductions (see table 1 below) and the removal of non-tariff barriers over time, for which they set up the non-tariff barrier reporting mechanism.

Table 1: Tariff reductions proposed across the AfCFTA

Source: Pearson Institute for International Economics, based on Economic Commission for Africa Data

Despite the potential gains and action points on implementation indicated above, the Agreement takes institutional dynamics and distributional effects as a given. The development of factor markets and how these influence the national and regional strategies of economic diversification, financial commitments and negotiations under the Agreement are front-burner issues within the broader objective of the AfCFTA building on other regional trade agreements.

Factor market

Regional Economic Communities (RECs), established to foster integration, form the bedrock for the implementation of the AfCFTA. The success of RECs in delivering their mandate has been hindered by the slow pace at which tariff and non-tariff barriers (NTBs) have been eliminated. This is the result of the high degree of diversity among members, significant differences in non-tariff barriers for both soft and hard infrastructures, large cost differences and costs lost to external producers that lead to trade diversions. These bottlenecks hinder the development of regional value chains and export diversification, which are chiefly influenced by how countries and regional blocs organise their productive factors.

Additionally, Article 19 (2) of the Agreement protects the gains and relationships made by countries and regions that have achieved higher levels of integration. The provision for differential treatment may cushion economies with weaker markets but generate negative externalities, such as the 15-year period for removal of tariffs by less developed countries such as Niger and Malawi (see table 1 above). Deliberations around the treatment of less developed countries in the region delayed negotiations in ECOWAS, with objections raised by officials from Morocco regarding the longer period of tariff removal for Nigeria, given the size of its economy.

On a regional scale, economies in Southern Africa produce more sophisticated exports because of their developed and integrated factor markets. Evidence from the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) shows that Botswana (90.1%), Central African Republic (76.14%), Mauritius (66.03%), South Africa (49.37%), Togo (64.86%) and Senegal (41.67%) have high manufacturing exports against their total export portfolio. In comparison, Angola (1.25%), Seychelles (11.01%), Mozambique (1.97%), Nigeria (6.69%) and Cote d’Ivoire (16.17%), have relatively low rates of export manufacturing capacities. Additionally, trade infrastructure that supports cross-border exports in Southern Africa has been in existence since 1910, compared to other economic communities.

Data from the Human Capital Index (HCI) puts South Africa, Mauritius, Botswana, Namibia, Lesotho and Zambia as the top economies with the largest share of high skilled labour required to engage in the manufacture of complex exports. The absorption of new technologies and the need to diversify manufactured goods to secure benefits from the AfCFTA depends on labour market factors such as mobility, productivity, healthcare conditions, innovation and education. Southern Africa outperforms all other regions in optimising labour for production, with Kenya following closely on innovative capacity.

The Global Competitiveness Index (GCI) Innovation Capability and ICT adoption indicator puts sub-Saharan Africa behind the rest of the world for technology development and utilisation in general. Yet this only forms a general view; the Tufts Fletcher School and the International Technology Union (ITU) have identified most Eastern and Southern African countries, with the exceptions of Nigeria, Egypt and Ghana, to be leading the way, indicating further disparities in the structures of the factor markets across the continent.

Another influential factor here is finance. ABSA Bank’s financial market index for 2020, which uses the capacity of local investors to finance economic activities as an indicator, identifies Namibia, Mauritius, South Africa, Morocco, Eswatini, Botswana, Nigeria, Seychelles, Kenya and Tanzania as the top performers, with Ghana and Egypt emerging as strong performers on policy and institutional architecture.

Political stability is fundamental to the productivity of factor markets. The World Bank designates this as one of the most important conditions for driving consistency in policy implementation for most African countries, particularly in West Africa. Only 8 out of 54 countries of the World Banks political stability in Africa index for 2020 are identified as being stable and not vulnerable to sudden changes in government, politically motivated violence or terrorism.

Negotiation bottlenecks

38 out of 54 countries had completed negotiations under phase 1 and deposited their negotiation instruments as of September 2021. Phase 2 of the negotiations commenced in 2021, with competition policy, intellectual property rights and investments forming core components. There were challenges with the negotiations in phase 1. The development of value chains and intra-regional markets could take on divergent trajectories and generate markedly different outcomes if the ‘conditional’ national clauses negotiated by member states, in accordance with Article (IV) of the Agreement, see the rights and obligations of one country differ from another.

Negotiations are envisaged to be undertaken at the level of countries or regional economic blocs. Therefore, countries that belong to custom unions will negotiate as blocs while those with complex manufacturing capacities will demand stricter rules of origin. The treatment of the least developed countries who are entitled to more extended periods for tariff liberalisation, form parts of regional blocks or that have not ratified the AfCFTA is of critical importance in future negotiations.

Additionally, the direct involvement of the private sector in high level negotiations is limited. The presence of non-state economic actors pursuing gains through enhanced integration at the regional level should be met with action from political leaders. The current strategy of countries, who already use established institutions in the private sector, consulting at the national level will generate varying implications for the widespread utilization of the provisions of the Agreement. The work of the Africa Business Council and other private sector led initiatives like AfroChampions will be important in generating support for the implementation of the Agreement in the private sector .

The distribution of technologies and innovation systems that facilitate the service economy and the status of intellectual property institutions carry the potential to unravel or delay negotiations. Out of the 54 countries on the continent, 13 do not have such institutions. The 11 who have adopted supra-national regulations (soft or hard) on anti-competition legislation must be supported to develop their institutions. It would be beneficial to consider the experiences of other member countries such as Zambia, Ethiopia, South Africa, Tanzania, Zambia and REC’s who have developed institutions like WAEMU, COMESA, EAC, ECOWAS and EMCC.

Financing of initiatives and projects

Non-African multilateral development organisations are financing strategic programmes and advocacy initiatives under AfCFTA. While this is positive in the short term, it could undermine the ownership and commitment of member states in the long term. The recent USD 3 million financing of the AfCFTA Secretariat by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) is part of a chain of initiatives financed by non-AfCFTA members. The pilot trade platform Africa Trade Observatory (ATO) was designed to collect and analyse trade data and monitor the implementation of the Agreement. Yet it is predominantly financed and managed by development partners: the EU finances the platform by EU 9.5 million and the International Trade Centre (ITC) manages the technical development of the platform.

Africa had similar financing challenges with the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD) prior to its reform in 2010, as most initiatives were financed by development partners. Evidence suggests that only 16 out of the 25 member countries that have both ratified the Agreement and committed to the Kigali Decision on financing the African Union have imposed the mandatory 0.2% levy on eligible imports. Domestic economic policies and international financial obligations, which are part of the flexible considerations provided by the instruments in the Kigali Decision, form most of the justifications provided by member countries for not imposing the levy.

Considering that members’ contributions range between USD 350,000 and USD 35 million, and the annual budget for the programme implementation in 2019 was USD 681.48 million, the contribution of non-African members is significant and presents the risk of ownership. The non-AfCFTA members provided 34 percent of the total budget in 2019 for financing operations of the African Union. African countries must match the commitments of non-African development partners by increasing their commitment to maintaining levies that support the financing of the Agreement, as well as fostering it’s domestication in their respective countries.

European support for AFCFTA

Africa intends to pursue a similar model to that of the European Union by creating a large single market area with free trade between its members. The EU could support mutually beneficial results with Africa through its knowledge of implementing tariff reductions, dealing effectively with non-tariff barriers and using broad stakeholder consultation in negotiating trade agreements. Nonetheless, as has been argued elsewhere, such success would be contingent upon the EU listening to what African governments and RECs actually want in regards to intra-African trade and trade with Europe.

Recommendations

Factor markets

Differences in productive resource endowments suggest that it will be near impossible to have an equal or equitable distribution of export manufacturing capacities. Nonetheless, policymakers can minimise factor market weaknesses by:

- Easing labour mobility through the full implementation of protocols on free labour. This will provide the opportunity for skilled labour in industry and manufacturing to be transferred to contexts where such capabilities are less available. Although not perfect, Southern and Eastern Africa are exemplary in this regard. Other regional blocks such as ECOWAS require more deliberate efforts, given the history of their countries setting aside the provisions on the free movement of persons.

- Supporting democratically fragile countries through the empowerment of regional parliaments that pass and enforce sanctions on leaders that disrupt governments in ways not foreseen by constitutions. The legislative powers of the East African Legislative Assembly, which takes precedence over national partner states, is a case in point. Productive factors are intrinsically connected to political stability and recent coups could slow down systematic approaches to capital formation. This has implications for developing production capacities, even if their comparative advantages can be determined.

- Building cross country infrastructure in energy and transport will support cross-border trade. The World Bank estimates this to cost about USD 47.6 billion per annum. A progressive example that moves towards the development of a natural gas market can be seen in the construction of the first cross border gas pipeline connecting Mozambique to South Africa by Sasol with support from the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA). The development of regional resources demand collective action on the part of countries in a regional bloc to both facilitate and protect investment. This improves regional and collaborative strategies towards curbing conflicts, as seen in the recent collaboration between Rwanda and oil giant Total towards protecting the regional infrastructure in the oil and gas value chain in Cabo Delgado (Mozambique) . This will better position the private sector to unlock the full potential of sustainable growth through trade, as investments expand in cross-border electricity, healthcare, transport, telecommunications and digitalisation.

Negotiations

As the second phase of negotiations progress, African leaders should be vigilant that the outcomes of these processes are critical to moving forward.

- Negotiators must ensure that additional complexities do not generate negative externalities for members that belong to more than one regional economic bloc.

- Institutional capacities for localisation are not homogenous across the continent. It is in the interest of the AfCFTA to foster the development of the institutions of weaker countries to be able to build their trade supporting infrastructures to the same operational levels.

- It is essential that the second phase of negotiations around competition policy, intellectual property (services and e-commerce) and investments be undertaken with broader stakeholder engagements and advocacy from the private sector, such as participation through the Africa Business Council.

Financing

The active domestication of provisions in the AfCFTA are significant. Of crucial importance are the financing of national and cross-country strategies for various initiatives under the Agreement.

- African countries must work individually and collectively to tap into domestic tax revenue, remittances from Africans in the diaspora, domestic savings, African direct investment, capital markets, sovereign wealth funds and the reversal of illicit financial flows.

- The continent generates over USD 520 billion in tax revenue and USD 168 billion from minerals and fuels annually, whilst holding USD 400 billion in reserve banks and more than USD 160 billion in sovereign wealth funds. This presents an opportunity for member countries to cooperate with each other while supporting regional initiatives that can mobilize finance to support the implementation of the AfCFTA.

- Cooperation between bilateral and multilateral development partners of Africa must focus on reform that addresses the inability of some member countries to honour their financial obligations towards the implementation of the Agreement. An example of this can be seen in the by the World Bank Group in 2020 towards Africa’s regional integration. This supported regional connectivity with sub-regional infrastructures, the development of regional value chains and the dissemination of inclusive private sector solutions across Africa to foster trade and capital flows.

- The African Union, under the AfCFTA, must address structural market deficiencies by designing strategies that support less endowed countries to mobilise funds towards implementing initiatives. This can be seen in the AU and Afrexim Bank led USD 5 billion compensation mechanism. This resolved short term fiscal losses and supported the medium to long term adjustments of production activities. Enterprises such as the USD 2.2 billion investment by MiGA to support cross border investment initiatives of the Eastern and Southern Africa Trade Development Bank and the Development Bank of South Africa should be expanded. Support must also be provided to tap into the USD 610 million support from the International Finance Corporation (IFC) towards capital market development in member countries to encourage export diversification. This will require member countries to commit their financing requirements under the African Union and the financing mechanisms of the AfCFTA.

About the Author

Patrick Stephenson is an economic consultant and the Senior Programmes Officer for International Budget Partnership in Ghana. He has consulted for bilateral, multilateral and multinational organizations in the areas of trade, public finance, market entry strategies and regulatory and financial compliance in 14 African markets. He is a Mandela Washington Fellow in Leadership and Civic Engagement, and a DANIDA Fellow on Aid Effectiveness in Africa.