Dive into the vital role of locally-led adaptation in Ghana's climate response, as highlighted in the research project 'Climate Change Adaptation: Strategies, Initiatives, and Practices,' urging national and global recognition and support to further effective and transformative local climate action.

Climate change poses an increasingly pressing challenge for Ghana, impacting sectors critical to its economy and human well-being. The increasing frequency and severity of climate-related disasters, from droughts and floods to coastal erosion, threaten to unravel decades of development progress. Against this background, several African nations, including Ghana, are actively implementing climate change adaptation policies and actions aligned with their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). However, the extent to which local needs, priorities, strategies, and challenges are integrated and emphasised in these efforts, particularly at the community level, remains unclear.

This policy brief, which is based on the results from the ‘Climate Change Adaptation: Strategies, Initiatives, and Practices Project in Ghana’ research project spanning from May 2022 to December 2023, emphasises the critical role of locally-led adaptation (LLA) in Africa's climate response. It explores the prospects, challenges, and opportunities that emerge when communities are empowered to lead the charge in climate adaptation. The brief highlights the challenges faced by communities, from limited resources to policy gaps, and the need for greater international support. It further highlights the immense opportunities that LLA actions present for Africa's sustainable development, community well-being, and global climate efforts as countries seek to unlock their adaptation potentials. The potential of locally-led adaptation is emphasised, and the brief calls for the recognition, empowerment, and amplification of the voices and context-specific needs of African communities in the fight against climate change.

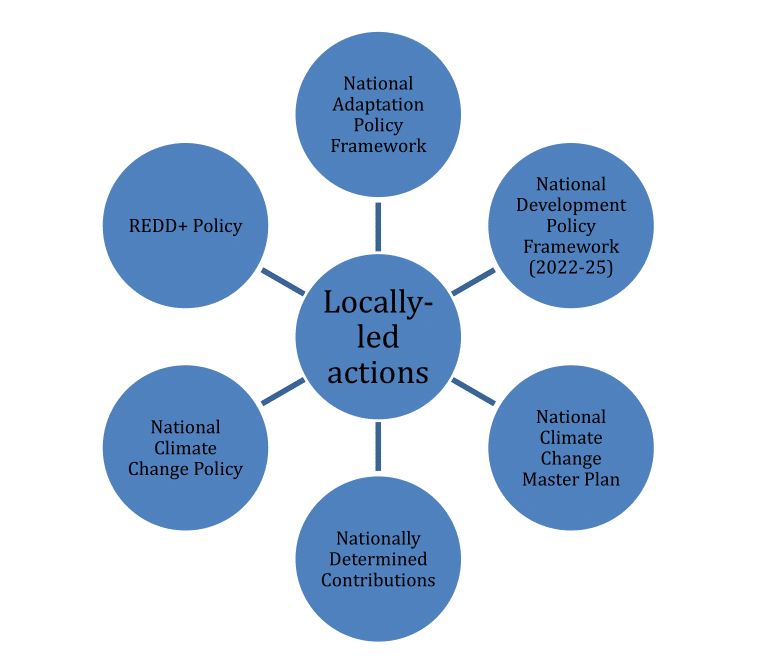

The brief starts by highlighting the key findings of the mapping of policies, strategies, and actions related to climate change in Ghana. It finds that the country’s NDC has a prominent focus on 13 specific adaptation measures, among a total of 47 action programs. These adaptation measures are thoughtfully categorised under 19 priority actions, with nine of them explicitly centred on adaptation initiatives. Ghana's updated NDC identifies several priority areas for adaptation, reflecting the nation's intent to tackle climate challenges comprehensively. In addition to the NDC, the research found the existence of several policies and strategies that support Ghana’s climate change agenda. These include the National Climate Change Policy (NCCP), the 2012 National Climate Change Adaptation Strategy (NCCAS), the 2015 NDCs, the National Climate Change Master Plan Action Programmes for Implementation (2015–2020), and the National Adaptation Policy Framework (2018), all of which guide climate actions and initiatives.

Key implementation strategies to build adaptive capacities at the local level include climate information services, integrated landscape planning, sea defence walls, early warning and disaster risk management, integrated water resource management, resilient community infrastructure, crop insurance, and promoting opportunities for improving the livelihoods and resilience of women and vulnerable groups. Climate actions in Ghana also involve a wide array of stakeholders, including technical agencies, directorates, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), the private sector, academic institutions, and international organisations. However, there is growing recognition among stakeholders that the on-the-ground implementation of adaptation actions at the sub-national level is still insufficient.

Further, the brief provides insights from three case studies, undertaken to learn about the motivations, strategies, practices, and challenges of locally-led adaptation. Here, the policy brief underscores the significance of placing local communities at the heart of climate change adaptation efforts.

These examples show how locally-led initiatives use nature-based solutions and awareness programs to enhance resilience and reduce vulnerability. Key challenges experienced by local communities are also highlighted. These challenges include limited financial resources hindering the implementation of LLA actions, inadequate institutional coordination, and policy gaps posing challenges to effective adaptation planning and implementation. Moreover, many communities face challenges in receiving support, including knowledge and logistical support from government institutions and other relevant organisations.

However, despite these challenges, key prospects and opportunities and entry points for enhancing effective and sustainable LLA efforts have emerged. These include strengthening community engagement and participation in decision-making processes to enhance the effectiveness of adaptation actions as well as building partnerships and collaboration between government, civil society, and the private sector to leverage resources and expertise for climate adaptation initiatives.

Based on the findings from the research, the following recommendations are proposed national policy makers and other stakeholders :

The following recommendations are proposed for the international community:

Climate change poses an increasingly pressing challenge for Ghana, impacting sectors critical to its economy and human well-being. Indeed, the country has been experiencing significant changes in weather patterns, resulting in severe climate-related risks such as drought, flooding, and erratic rainfall.1 Ghana is currently ranked 109 out of 181 countries in the 2020 ND-GAIN Index.2 This is due both to its dependence on climate-sensitive sectors such as agriculture and forestry3, and its geographical location and socio-economic conditions, which heighten the country’s susceptibility to the adverse effects of climate change.4 The increasing frequency and severity of climate-related disasters, from droughts and floods to coastal erosion, threaten to unravel decades of development progress as the nation strives to achieve its Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Recognising this vulnerability, and to address these impacts and challenges, Ghana is actively implementing climate change adaptation policies and actions. The government has developed several policies, strategies, and actions, including the National Climate Change Policy Framework and the updated Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) to guide its climate change response. These strategies focus on building the adaptive capacity of vulnerable communities, enhancing the resilience of key sectors (such as agriculture), and promoting low-carbon development pathways. In addition to the government's efforts, various private firms, non-governmental organisations, and civil society groups are working on climate change adaptation and mitigation initiatives at different levels.

However, the extent to which local needs, priorities, strategies, and challenges are integrated and emphasised in these efforts, particularly at the community level, remains unclear. Thus, while Ghana is making efforts to align its climate adaptation policies with its NDCs, there is a critical need to prioritise locally-led adaptation strategies. These strategies, developed and implemented by local entities and communities themselves, have the potential to significantly enhance the effectiveness, inclusivity, and sustainability of Ghana's climate adaptation efforts. This policy brief draws on research undertaken by the Africa Policy Research Institute (APRI), implemented in close collaboration with the Ghana Climate Change Innovation Centre (GCIC) and a diverse range of stakeholders, including local communities and policymakers at all levels of the government. The brief emphasises the critical role of locally-led adaptation in Ghana and Africa's climate response, highlighting the prospects, challenges, and opportunities that emerge when communities and local actors are empowered to lead the charge in climate adaptation. It also provides recommendations to local and international policymakers and partners on how to support and implement effective and long-term adaptation processes to address the twin challenges of climate change and sustainable development in Ghana, without undermining or unnecessarily constraining the policy space of local policymakers or the general well-being of individuals and the broader community.

This qualitative study employed multiple research methods. It began with a comprehensive review of the literature and relevant climate change documents to establish the existing knowledge and policy landscape. This was followed by mapping exercises to identify climate change policies, strategies, local actions, and key stakeholders in the country. Stakeholder engagement played a crucial role in gathering insights and perspectives. Two policy-convening workshops were conducted, bringing together senior officials from various institutions involved in climate action. These workshops provided a platform to discuss successes, challenges, and progress related to LLA efforts in Ghana. To gain in-depth understanding informed by the literature review and inputs from key stakeholders, three case studies were selected:

Ghana has developed and updated its NDC to accelerate climate action. The updated NDC emphasises 13 specific adaptation measures out of a total of 47 programmes of action. Key priority areas for adaptation include the development of resilient infrastructure, the promotion of livelihoods, strengthening of agricultural landscapes and food systems, urban planning, early warning systems, enhancing the climate resilience of women and vulnerable groups, and promoting social inclusion.

In addition to the NDC, there are several policies and strategies that support Ghana’s climate change agenda. These include the National Climate Change Policy (NCCP), the National Climate Change Adaptation Strategy (NCCAS) of 2012, the 2015 NDCs, the National Climate Change Master Plan Action Programmes for Implementation (2015–2020), and the National Adaptation Policy Framework (2018), all of which guide climate actions and initiatives.

Key implementation strategies to build adaptive capacities at the local level include climate information services, integrated landscape planning, sea defence walls, early warning and disaster risk management, integrated water resource management, resilient community infrastructure, crop insurance, and promoting opportunities for improving the livelihoods and resilience of women and vulnerable groups.

Moreover, Ghana’s commitment to climate action is evident through the diverse range of stakeholders engaged in addressing climate change impacts at various levels. These stakeholders, including technical agencies, directorates, NGOs, the private sector, academic institutions, international organisations, local authorities, and communities, play pivotal roles in advancing climate resilience. However, there is growing recognition among stakeholders that the on-the-ground implementation of adaptation actions at the sub-national level is still insufficient.

The mapping and stakeholder engagement showed significant gaps and challenges in the national response to climate change, including the following:

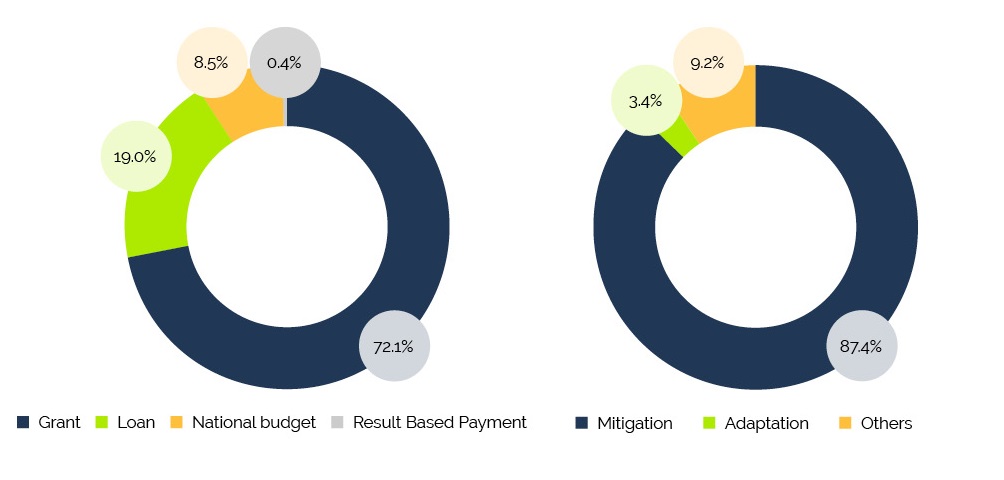

Figure 1: Sources and Allocation of climate finance (2011-2019) | Source: Author’s construct, 2023, based on EPA & MESTI (2020)

Also, while Ghana's NDCs estimate the cost of adaptation measures between US $9.3 billion and US $15.5 billion up to 2030, the available financial resources, including domestic budgets and international climate finance contributions, are inadequate; the government has indicated it can only provide a quarter of this estimate (i.e. unconditional funding).

Despite the stated limitations, communities have been implementing several strategies, initiatives, and practices to adapt to the impacts of climate change. This section highlights key findings from three case studies that were undertaken to explore the motivation, strategies, outcomes, challenges, opportunities, and entry points for effective and sustainable local adaptation actions.

This case study focuses on the experiences of two communities, Kpiri and Sor No. 1, situated in the West Gonja district of the Savannah Region in Ghana. These communities grapple with growing vulnerability to climate change-induced impacts, including rising temperatures, unpredictable rainfall patterns, and prolonged droughts. These environmental challenges disrupt traditional agricultural practices and compound issues like food insecurity and economic hardships, particularly among women. In response to these pressing issues, the local non-governmental organisation, MORE Women, has taken up the mantle of facilitating an adaptation initiative suggested by the community members themselves to improve their income generation and resilience. The approach centres on establishing Village Savings and Loans Associations (VSLAs) and introducing group-based organic shea processing. This locally-led approach leverages local resources and traditional wisdom. The core adaptation strategies encompass the formation of VSLAs, enabling women to engage in group-based organic shea processing and community-driven initiatives, including the enactment of local by-laws against logging and charcoal production as well as participation in tree-planting efforts. Notable motivations driving the adoption of these strategies include diversifying livelihoods, augmenting income, restoring ecosystems, reducing dependence on charcoal and firewood, and enhancing food production.

The case study showed promising outcomes during this research. These include heightened access to credit for women through VSLAs, serving as a safety net during economic stress stemming from climate change. Moreover, the adaptation actions promote environmental conservation through organic farming practices and reduced reliance on harmful chemicals. This approach not only furnishes women with a dependable income source but also fortifies their resilience against climate-induced vulnerabilities.

Furthermore, the study reveals multiple co-benefits, encompassing enhanced conflict resolution skills and unity among rural women, financial autonomy via credit access, and improved gender equality manifested through women's participation in decision-making processes. These outcomes contribute to community development and have a positive impact on the social, economic, and environmental well-being of women and their families.

The case study conducted in the Pindaa and Kuliya communities within Ghana's Upper East region sheds light on a transformative initiative led by the Organisation for Indigenous Initiatives and Sustainability (ORGIIS-Ghana). This initiative is designed to restore degraded savannah forests and simultaneously fortify local livelihoods through the adoption of climate-smart agricultural practices. The driving force behind this effort is the urgent need to respond to the adverse impacts of climate change, which include rising temperatures, unpredictable rainfall patterns, and prolonged droughts. These climatic challenges have taken a severe toll on traditional farming practices, resulting in diminished crop yields, heightened food insecurity, and exacerbated economic struggles among the local population.

The core objectives of the initiative encompass bolstering food security, augmenting household incomes, revitalising ecosystems, and fostering biodiversity conservation. To achieve these goals, a suite of climate-smart agricultural practices has been implemented, including conservation agriculture, tree planting, solar-powered irrigation, and the adoption of agroecological techniques. These practices collectively contribute to enhancing soil fertility, mitigating soil erosion, and improving water resource management, thereby promoting the sustainable use of natural resources.

Key outcomes identified of this project include enhanced food security, improved soil health and fertility, and increased agricultural productivity. Additionally, co-benefits are realised, encompassing the effective control of soil erosion, improved livestock well-being, the potential for carbon sequestration, and social advantages such as strengthened community cohesion and empowerment. Nonetheless, challenges persist, including limited water resources for agricultural purposes, inadequate policy support for locally-led adaptation initiatives, entrenched gender norms that restrict women's land management rights and decision-making authority, and the reliability of solar panels for water pumping. Within these challenges, however, opportunities emerge: promoting community-based land management practices, creating livelihood opportunities for youth and women, and fostering community cohesion and empowerment through knowledge and resource sharing. These represent potential pathways for further development.

This case study is about the community-based disaster risk reduction efforts of the people in Ketu South and Anloga districts (i.e. Keta-Ada stretch) aimed at responding to coastal erosion and impacts of climate change such as sea-level rise and erosion of coastal lands. The communities engaged were: Fuveme, Dzita, Anyanui, Salakope, Adina, Agavedzi, and Blekusu. The case study highlights the locally-led initiatives undertaken by the communities to reduce their vulnerability to these risks and enhance their resilience. The research showed that the communities recognise the significant threat posed by coastal erosion to their homes, livelihoods, and infrastructure due to climate change impacts such as rising sea levels.

In response to this challenge, they have taken several measures and empowered themselves with knowledge of adaptive practices that will enable them to reduce their vulnerability and enhance their resilience to coastal erosion. These initiatives involve strategies such as community engagement, where residents actively participate in the identification of risks; creation of water passages (Dual canals), which limit the extent of vulnerability that often comes along with the sea erosion; transnational fishing; relocation of households; establishment of community-based early warning systems to alert residents about impending coastal hazards so that evacuation, if necessary, can be timely and the potential loss of life minimised; implementing nature-based solutions such as mangrove restoration and beach nourishment; and general awareness programs that enhance the community's understanding of coastal hazards and the importance of preparedness. The motivation for these actions include: the need for protection of homes and livelihoods from the impacts of erosion and other climate change-related risks; the need to enhance livelihood sources; improving income levels; improving fishing activities; and the need to take action to minimise the destruction of properties. The outcomes and co-benefits resulting from this study include enhanced biodiversity and ecosystem services through the use of nature-based solutions—such as the planting of mangroves and the restoration of wetlands—as well as increased social cohesion and community empowerment.

The main challenges include: limited access to financial resources; limited institutional support, especially from the local authorities and the central government; limited livelihood options available to the residents; and non-adherence of by-laws implemented by the community against sand winning and other practices that exacerbate the impact of the coastal erosion on the people. Despite these challenges, some available opportunities include: the construction of sea defences at strategic coastal locations; provision of livelihood opportunities for coastal residents affected by sea erosion and coastal floodings; enhancement of infrastructural development such as the construction of dual canals; and improving community cohesion to implement strategic adaptation measures against the impacts of sea erosion and coastal flooding.

The value of such actions is multifold. At the local level, they help safeguard lives, livelihoods, and infrastructure from the immediate threats of coastal erosion and flooding. By actively participating in the planning and implementation of these measures, the communities build their capacity to respond effectively to future climate-related hazards. On a national scale, community-based disaster risk reduction efforts contribute to the overall climate resilience agenda.

By reducing the vulnerability of coastal communities, these actions align with national policies and strategies for adaptation and disaster risk management. The knowledge and lessons learned from these local initiatives can inform and guide broader coastal management and climate change adaptation efforts across the country. This locally-led adaptation action is well-aligned with the NCCAS of 2012,7 the NDCs of 2015 and its updates in 2021,8 the National Climate Change Master Plan Action Programmes for Implementation (2015–2020),9 and the NAPF of 2018.10 Internationally, the case study demonstrates the importance of grassroots-level adaptation and resilience-building measures. The experiences and best practices from the Keta-Ada communities can serve as valuable examples for other coastal regions facing similar challenges worldwide. Thus, these case studies enhance local resilience, align with national policies, and provide valuable insights for global efforts in addressing climate change impacts.

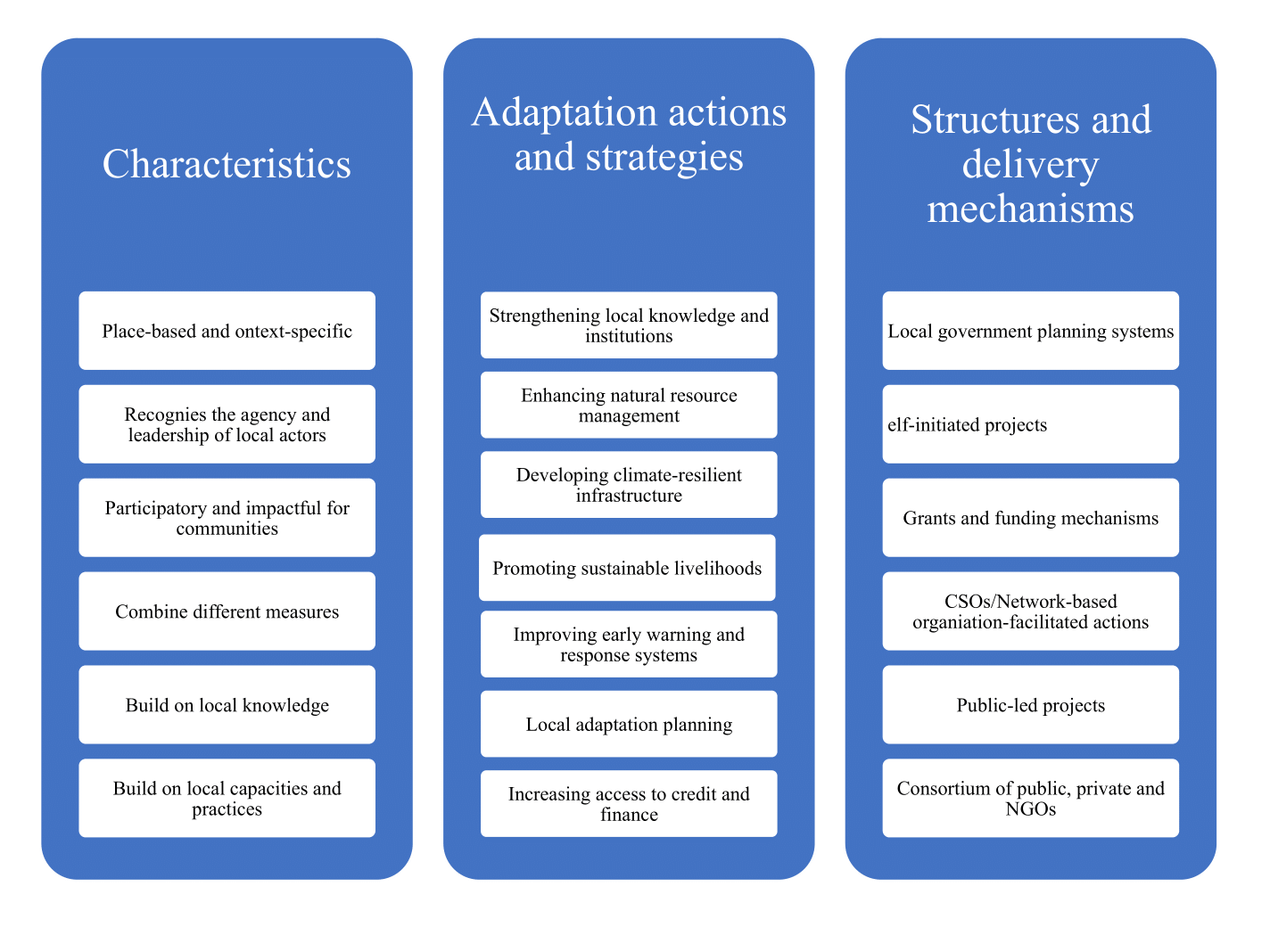

The significance of locally-led adaptation actions, as exemplified in the findings of the research highlighted above, has relevance across multiple dimensions – from the local to the national and international levels. The stakeholders engaged in this project collectively recognised that the prevailing approach to adaptation planning and implementation in Ghana suffers from top-down dynamics, lacks coordination, and lacks robust local leadership. This inherent limitation hampers the overall effectiveness of adaptation efforts. Consequently, there is a growing consensus that transitioning from the current paradigm towards locally-led adaptation remains central to effectively addressing the impacts and vulnerabilities arising from climate change. Some of the features of locally-led adaptation based on insights gained from the research are shown in Figure 2 below. These insights highlight that: (i) LLA champions grassroots approaches to enhance the facilitation and financing of local initiatives, and (ii) LLA places a stronger emphasis on local leadership and decision-making in adaptation processes.

Figure 2: Summary of unique characteristics of locally-led adaptation actions, strategies, and delivery mechanisms in Ghana (Source: Author’s construct, 2023)

‘Local’ in the context of locally-led adaptation (LLA) is defined to mean those individuals and communities at the forefront of climate change impacts. This includes both formal and informal institutions below the national level which are directly accountable to local populations. Consequently, LLA is place-based and context specific; it recognises the agency of local actors, is participatory in nature, builds on local knowledge, and prioritises the involvement of local communities, organisations, and governments as decision-makers in adaptation interventions, endowing them with agency over the process.11 This agency pertains specifically to defining, prioritising, designing, monitoring, and evaluating adaptation initiatives.

LLA also involves collaboration with higher levels of governance to implement and deliver these solutions. LLA goes beyond mere participation of local communities in decision-making or the mere implementation of predetermined options shaped by external actors. To the contrary, LLA is place-based and context specific, recognises the agency of local actors, is participatory in nature, and builds on local knowledge. Overall, LLA champions grassroots approaches to enhance the facilitation and financing of local initiatives. Its primary aim is to empower local communities and institutions to take the lead in adaptation endeavours, moving away from superficial involvement. LLA recognises the knowledge of local people, promotes sustainable and effective solutions and aligns with the principles of participatory and equitable decision-making.12 Thus, LLA emphasises the importance of building on existing social, economic, and environmental systems, rather than imposing external solutions that may not be sustainable or effective in the long-term.13 Furthermore, LLA prioritises communities as drivers of adaptation initiatives. Indeed, the case studies show that LLA is inherently initiated and led by local communities themselves. Thus, although external organisations may play a supportive role, the impetus for action comes from within the community in the form of local leadership and decision-making. Insights from the research further show that LLA can bring several benefits towards improving adaptation policies and addressing problems of inadequate funding, limited local implementation, limited coordination, and top-down adaptation decisions. Some of the benefits that emerged from the study across local, national, and international levels are outlined below.

Figure 3: Illustration showing how local adaptation cases align with some climate policies, strategies, and frameworks (Source: Author's construct, 2023)

Shifting policy attention towards LLA brings with it the potential to significantly enhance the implementation and sustainability of adaptation actions. The case studies conducted in various communities have demonstrated that LLA policies offer numerous advantages in ensuring that climate actions are not only effective but also sustainable in the long run. One of the key strengths of LLA is its ability to anchor climate actions in the specific needs, vulnerabilities, and capacities of local communities. This targeted approach results in adaptation measures that are highly relevant to the unique challenges faced by these communities. Consequently, the ownership and alignment between adaptation actions and local conditions greatly enhances the effectiveness of these measures.

Thus far, governments have generally struggled to access international climate finance. However, since the urgency for increased climate adaptation efforts was underscored in the sixth Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) assessment report,14 there has been a proliferation of funding opportunities aimed at assisting climate-vulnerable countries like Ghana. These opportunities encompass direct access mechanisms such as the Adaptation Fund, as well as alternative channels like the Global Environment Facility (GEF), the Green Climate Fund (GCF), and the Local Climate Adaptive Living Facility (LoCAL). Emphasising a culture where communities are empowered to independently plan and execute projects will play a pivotal role in ensuring sustainable and efficacious access to these funds and the implementation of associated interventions.

A greater shift to locally-led adaptation will enable the government to access these adaptation resources by yielding at least five primary advantages. First, locally-led adaptation (LLA) projects are often community-driven and aligned with the specific needs and priorities of local areas. When these projects are well-designed, they become viable candidates for climate finance support, since their relevance and strong community engagement can make them attractive to funders. Second, LLA initiatives can be designed to align with national climate adaptation strategies and priorities. This alignment enhances their eligibility for funding, as they contribute directly to the achievement of national adaptation goals and targets. Third, LLA actions generate valuable data and evidence regarding the effectiveness of different strategies and interventions. This data can be used to demonstrate the impact and feasibility of adaptation projects, making them more compelling for financiers who require evidence-based decision-making. Fourth, by empowering local communities and organisations to take the lead in adaptation efforts, governments can indirectly build implementation capacities at the grassroots level. Strengthened local capacities improve the chances of successful project execution, which funders often consider when allocating resources. Last but not least, governments can facilitate LLA by establishing governance structures that support community involvement in decision-making. These structures can be recognised and supported by climate finance institutions, reinforcing their legitimacy.

There are several opportunities available to the Ghanaian government to unlock the adaptation potentials of Ghana through prioritisation of locally-led adaptation. First, communities are already actively participating in different actions to adapt to the changing climate and its impact on their lives and livelihoods. Results from the three case studies show that local communities are using local knowledge and practices related to their local ecosystems, natural resources, and weather patterns to engage in climate-smart agriculture; community-based conservation and land management actions; community-led irrigation systems; energy-efficient cooking stoves; recycling of waste; and local home elevation. These diverse strategies provide opportunities for the Ghanaian government to learn from and build consciously on the wealth of local practices to develop and implement adaptation actions in various sectors. Tapping into these opportunities will ensure that local communities’ priorities, resources, and needs are centred in adaptation policies and implementation efforts across all levels of government. In addition to these opportunities, there are several entry points for the Ghanaian government and the international community to strengthen the role of LLA in climate action processes and action, such as:

Based on the research, the following recommendations are made for the Ghanaian policymakers and other stakeholders operating in the field of climate change to ensure that communities are better equipped to address the challenges of climate change and build resilience in their local contexts.

Ghana is grappling with pronounced climate vulnerabilities spanning agriculture, health, coastal regions, and natural resources. These vulnerabilities demand swift and targeted responses. In the face of these challenges, Ghana stands at a critical juncture where the embrace of LLA holds immense promise and potential. Local communities, the front line of climate change impacts, are endowed with a wealth of knowledge concerning their unique vulnerabilities and the most effective strategies for adaptation. This policy brief underscores the pivotal role that LLA can play in Ghana's climate resilience journey, highlighting key imperatives and opportunities.

The brief has emphasised that the updated NDC blueprint lays out a comprehensive framework for climate adaptation, encapsulating 13 specific measures and priorities across multiple sectors. LLA harmonises seamlessly with these priorities, placing resilience-building, sustainable development, and the empowerment of vulnerable communities at the forefront. Also, while adequate financing is the lifeblood of effective adaptation, channelling resources efficiently at the grassroots level enables LLA to become an essential catalyst in the nation's pursuit of climate resilience.

As Ghana seeks to implement these ambitious adaptation measures, it has encountered a formidable barrier in the form of limited financial resources. The gap between the required funding and the national budget's capacity is significant. At the same time, challenges with coordination and the low dedication of funds to subnational levels continue to constrain implementation of adaptation. In this context, LLA offers a path forward, stretching available resources further and maximising their impact.

The policy brief has highlighted that LLA initiatives are underpinned by a wide variety of motivations, from enhancing livelihoods to restoring ecosystems and empowering communities. These diverse drivers of change converge and steer the nation toward resilience. Meanwhile, the LLA practices, ranging from energy-efficient stoves to tree-planting and organic farming, seamlessly align with the priorities articulated in the NDC, underscoring the strategic role of LLA in driving climate action forward. Thus, the integration of locally-led adaptation into Ghana's climate agenda represents a pivotal shift. It would empower communities to become architects of their own climate destiny, align seamlessly with national priorities, and provide a beacon of hope in a climate-uncertain world.

While challenges persist, from resource constraints to policy gaps, these obstacles should not deter progress, but rather galvanise efforts to amplify the voices of communities in adaptation response. By prioritising and investing in locally-led actions, the Ghanaian government can unlock a wealth of opportunities and support communities to innovate, adapt, and thrive, transcending the limitations that top-down approaches impose. By recognising, amplifying, and championing the invaluable contributions of LLA, Ghana can embark on a journey toward a more resilient, sustainable, and climate-resilient future.

In this case, the international community can also play a pivotal role. Collaboration, knowledge sharing, and financial support are essential elements in realising the potential of locally-led adaptation. We must foster partnerships that extend beyond borders and bureaucracies, nurturing a collective spirit to address one of humanity's greatest challenges. Conclusively, the path forward is clear: To strengthen adaptation potential, actors must embrace and champion locally-led actions. By placing communities at the forefront, we enhance our collective ability to confront climate change head-on and secure a sustainable and prosperous world for all.

[1] EPA & MESTI. (2020). Ghana’s Fourth National Communication to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Environmental Protection Agency. Available at: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/Gh_NC4.pdf

[2] Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative. (2020). ND-GAIN country index. The University of Notre Dame.

[3] MESTI. (2013). Ghana National Climate Change Policy. Ministry of Environment, Science, Technology and Innovation, Republic of Ghana. Available at: https://www.un-page.org/files/public/ghanaclimatechangepolicy.pdf

[4] MESTI. (2013). Ghana National Climate Change Policy. Ministry of Environment, Science, Technology and Innovation, Republic of Ghana. Available at: https://www.un-page.org/files/public/ghanaclimatechangepolicy.pdf

[5] EPA & MESTI. (2020). Ghana’s Fourth National Communication to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Environmental Protection Agency. Available at: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/Gh_NC4.pdf

[6] Oduro-Ofori, E., Isahaka, F., & Opoku-Antwi, G. (2021). Evidence of implementation of climate change adaptation programs by selected local governments in the Ashanti region, Ghana. GeoJournal, 1-17.

[7] UNEP & UNDP. (2012). National Climate Change Adaptation Strategy (Ghana). United Nations Development Programme. Available at: https://www.adaptation-undp.org/sites/default/files/downloads/ghana_national_climate_change_adaptation_strategy_nccas.pdf

[8] MESTI. (2021). Ghana: Updated Nationally Determined Contribution under the Paris Agreement (2020 – 2030). Environmental Protection Agency, Ministry of Environment, Science, Technology and Innovation, Accra. Available at: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/NDC/2022-06/Ghana%27s%20Updated%20Nationally%20Determined%20Contribution%20to%20the%20UNFCCC_2021.pdf

[9] MESTI & NCCC. (2015). The National Climate Change Master Plan Action Programmes for Implementation: 2015-2020. The Ministry of Environment, Science, Technology and Innovation, Republic of Ghana. Available at:https://www.weadapt.org/sites/weadapt.org/files/ghana_national_climate_change_master_plan_2015_2020.pdf

[10] NAPF. (2018). Ghana’s National Adaptation Plan Framework. Environmental Protection Agency. Available at:https://napglobalnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/napgn-en-2018-ghana-nap-framework.pdf

[11] Soanes, M., Bahadur, A. V., Shakya, C., Smith, B., Patel, S., del Rio, C. R., ... & Mann, T. (2021). Principles for locally-led adaptation.International Institute for Environment and Development, London, UK.

[12] Rahman, M. F., Ladd, C. J., Large, A., Banerjee, S., Vovides, A. G., Henderson, A. C., ... & Huq, S. (2023). locally-led adaptation is key to ending deforestation. One Earth, 6(2), 81-85.

[13] Westoby, R., Clissold, R., McNamara, K. E., Ahmed, I., Resurrección, B. P., Fernando, N., & Huq, S. (2021). Locally-led adaptation: Drivers for appropriate grassroots initiatives. Local Environment, 26(2), 313-319.

[14] Chow, W., Dawson, R., Glavovic, B., Haasnoot, M., Pelling, M., & Solecki, W. (2022). IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (AR6): Climate Change 2022-Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability: Factsheet Human Settlements

Dr. Albert Arhin is the Lead Researcher for the project “Climate Adaptation Strategies and Initiatives: Issues and Pathways in Ghana”. Dr. Arhin is a sustainability expert with more than fifteen years of experience in research, technical support and strategic planning in climate change, REDD+ and land restoration policies, green economy and sustainable development.

Richard Oblitei Tetteh is a Research Assistant for the project “Climate Adaptation Strategies and Initiatives: Issues and Pathways in Ghana”. Richard is an Agricultural Extension and Development Specialist with over four years of experience in stakeholder engagement, sustainable rural development, climate change studies, monitoring and evaluation studies, social research, workshop facilitation, and project planning and management.