About the Series

APRI is actively generating knowledge and shaping debate on key topics related to energy and climate diplomacy, aiming to strengthen the relationship between Europe and Africa. The Green and Transition Minerals Collection provides in-depth African perspectives, empowering policymakers to leverage resources essential for Europe's energy transition and Africa's industrialization.

Key Takeaways

- A new industrial revolution focused on green and digital technologies is accelerating, as major economies develop critical minerals strategies to prioritize decision making, guide investment and strengthen supply chains.

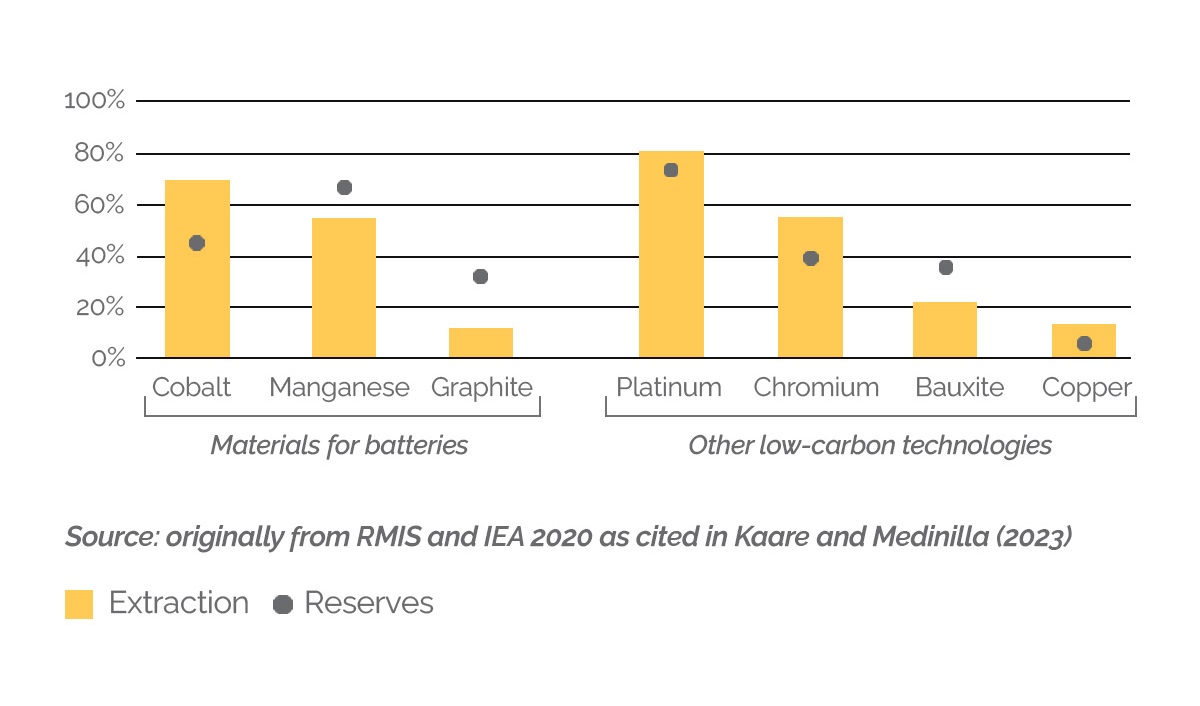

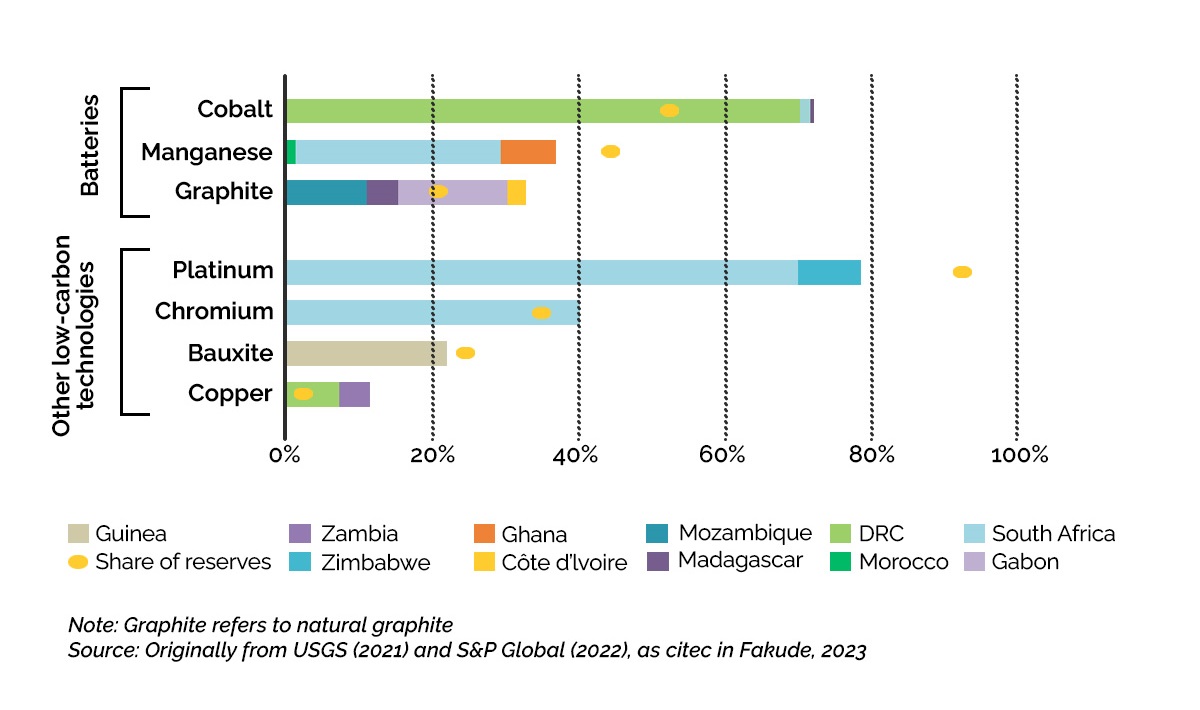

- While Africa is undeniably rich in critical minerals, with a large proportion of global production in both extracted and reserves of several critical minerals, African countries are locked into commodity dependence, trapped at the lowest end of global value chains.

- The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) offers a historic opportunity for the continent to build regional value chains in critical minerals and low carbon technologies, in the face of growing competitiveness between major economies.

- Africa’s strategy for critical minerals should be considered within the context of its unique ‘just transition’ to a low carbon economy. However, the concept of the ‘just transition’ needs a clearer definition from an African perspective.

- To achieve this, African countries would need to adopt a ‘developmental regionalism’ approach to the AfCFTA that advances their CRD pathways, namely ‘climate resilient developmental regionalism’. This ‘climate-resilient developmental regionalism’ approach integrates climate resilience across all four pillars of the ‘developmental regionalism’ approach: adopting the principle of special and differential treatment; building regional industrial value chains; cross-border infrastructure development cooperation; and adherence to democratic governance.

Geoeconomics and geopolitics of critical minerals and green technologies

Many countries have developed critical minerals strategies to prioritize decision making, guide investment and strengthen supply chains. These strategies, including their list of ‘critical minerals’, often overlap among nations like the United States (US), Canada, the European Union (EU), the United Kingdom (UK), South Korea and Japan, and share a common aim: to address perceived risks from supply chain disruptions and security from an overreliance on China as a key player in critical mineral supply chains. The COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine have drawn attention to issues of dependence in commodity supply chains that are critical to health, food and energy security, highlighting the need for greater risk management.

The policy brief sets out the critical minerals strategies of the US, EU, UK and Canada, to illustrate the global race underway to secure these minerals for ongoing green and digital industrial revolutions. It also provides a brief account of China’s strategy on critical minerals, electric batteries and new energy vehicles. In closing, it contextualizes the challenges and opportunities facing African countries as they pursue industrialization in these new green or sustainable technologies.

US and the ‘Bidenomics Bills’

The US has developed a long-term strategy to secure critical minerals and reduce dependencies on foreign sources, dating back over a decade (National Research Council, 2007). This strategy is evident in various government initiatives, such as the US Department of Energy’s 2021-2031 strategy document (US DOE, 2021) and the US Geological Survey’s list of 50 critical minerals after extensive multi-agency assessments (USGS, 2022). The US Critical Materials and Minerals Strategy focuses on diversifying supply, developing substitutes and improving reuse and recycling to secure supply of critical materials for national security and economic purposes.

Recent legislation, called the ‘Bidenomics Bills’, have reinforced this strategy. These bills include the 2021 Infrastructure, Investment and Jobs Act; the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act (IRA); and; the 2022 CHIPS and Science Act. Respectively, they form the ‘backbone,’ ‘engine’ and ‘brains’ of the US approach and were designed to re-build the US economy post-COVID and drive their green industrial revolution (Gabor et al, 2023).

Boasting an estimated worth of USD 369 billion up to 2032, the IRA approach to decarbonization focuses on domestic production and investment subsidies, rather than regulation or emission targets as the EU has done (Franco-German Economic Council, 2023). This approach drew criticism from the EU and other countries for allegedly contradicting World Trade Organization (WTO) principles for imported and domestically produced goods after clearing customs, amongst other agreements, including the Trade Related Investment Measures and the Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (Franco- German Economic Council, 2023).

The massive subsidies provided by the IRA to US-based manufacturers and multinational companies led to the EU Commission formally expressing ‘serious concerns’, even considering ‘retaliatory measures’ or filing a complaint with the WTO on provisions that violate their rules.

The EU further stated that there was a very real risk of the IRA ‘luring some … EU businesses into moving investments to the US’ and incentivizing EU automakers to relocate production across the Atlantic (Henley and Rankin, 2023). However, a statement by the Franco-German Economic Council argued this could be futile and proposed that cooperating with the US on subsidy rules, deepening trade cooperation and establishing a shared framework would be more efficient (Franco- German Economic Council, 2023).

Box 1: How the IRA influenced Tesla

The IRA provides USD 7,500 subsidies for US-made electrical vehicles (EV), excluding those with Chinese-made components. This has spurred US EV manufacturer, Tesla, to secure critical mineral supplies, reducing their dependence on China for their lithium- ion batteries. In 2022, Tesla signed an agreement with Australia’s Syrah Resources for graphite from Balama, Mozambique and with Glencore for cobalt to manufacture lithium-ion batteries in Giga-factories located in Berlin and Shanghai (Andreoni and Roberts, 2023).

EU’s reaction to the IRA

European Commission President von der Leyen emphasized that: ‘without secure and sustainable access to the necessary raw materials, our ambition to become the first climate neutral continent is at risk’ (EU, 2022). This sentiment was echoed by the current European Commissioner for Internal Market, Thierry Breton, who stressed the strategic importance of critical minerals in the EU’s digital and defence capabilities (EC, 2022). Subsequently, the EU launched the Critical Raw Materials Act in March 2023 towards securing green and digital supply chains.

In response to the US IRA, the EU announced its new Green Deal Industrial Plan, allocating EUR 510 billion (~ USD 550 billion) to bolster its own sectors such as wind and solar, heat pumps, clean hydrogen, and energy storage. This plan includes funding from Next Generation EU program and RepowerEU fund and relaxes state aid rules for member states like France and Germany to subsidize domestic manufacturing (Franco-German Council, 2023). However, it lacks additional funds for smaller EU member states with limited financial capacity to support their home industry (Andreoni and Roberts, 2023).

Furthermore, the Temporary Crisis and Transition Framework (TCTF), adopted in March 2023, intends to boost and retain clean tech investments in Europe. To match US subsidies, the TCTF provides public support in strategic sectors (such as clean and digital technologies) and tax credits. This Scheme complements existing EU programs like RepowerEU for renewables and the European Chips Act for states supporting semiconductor value chains. (Franco-German Economic Council, 2023). Consequently, subsidy announcements by individual member states have soared in the EU (Franco-German Economic Council, 2023).

UK Green Industrial Revolution plans

The UK’s Critical Mineral Strategy, launched in 2022, follows on the heels of US, Canada, Japan, and Australia, and seeks to improve the resilience of critical minerals supply chains. The strategy prioritizes lithium, cobalt and graphite for electric cars batteries; silicon and tin for electronics; and rare earth elements for electric cars and wind turbines.

It also includes an Automotive Transformation Fund to support a UK zero-emission vehicle supply chain. The UK’s former Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, Rt Hon Kwasi Kwarteng articulated the importance of critical minerals for the country’s energy transition; economic growth; and national security, to ensuring the UK’s positioning in the “new Green Industrial Revolution... [as] a leading player in the global race for critical minerals” (UK Government, 2023).

The UK’s “Ten Point Plan for a green industrial revolution”, declared the end of new petrol and diesel car and van sales by 2030, and full zero-emission compliance for new vehicles by 2035. To support this, up to GBP 850 million (~ USD 1081 million, ~ EUR 998 million) is being invested in late-stage research and development; and industrialization projects, to establish an internationally competitive zero-emission vehicle supply chain in the UK. An additional GBP 22 billion (~ USD 28 billion, ~ EUR 26 billion) of financing capacity is to be deployed by the new government-owned UK Infrastructure Bank (UKIB), dedicated to increasing infrastructure investment nationwide. Finally, the Industrial Energy Transformation Fund (IETF), with a further GBP 315 million (~ USD 400 million, ~ EUR 370 million), supports energy-intensive businesses – including eligible critical mineral companies – in reducing energy costs and carbon emissions through energy efficiency and decarbonization technologies (UK Government, 2020).

Box 2: EU member states transform state aid to subsidize domestic production

Spurred on by the TCTF, several EU member states responded with their own national subsidy programs. Spain, for instance, secured EUR 3.5 billion (~ USD 3.8 billion) in state aid from the EU, including EUR 837 million (~ USD 907 million) to subsidize battery manufacturing. They also subsidized EUR 450 million (~ USD 488 million) to ArcelorMittal for hydrogen-produced steel and EUR 650 million (~ USD 704 million) for 5G infrastructure. Germany’s approved aid totalled EUR 6.3 billion (~ USD 6.8 billion) and it committed several hundred million euros to the Swedish battery manufacturer Northvolt (Franco-German Economic Council, 2023). Out of France’s state aid allocation of EUR 8.6 billion (~ USD 9.3 billion), it promised EUR 850 million (~ USD 921 million) in support to the ACC gigafactory for producing automobiles batteries.

Source: Franco-German Economic Council, 2023

Canada’s roadmap towards global leadership

Canada possesses a wealth of natural resources, including critical minerals essential for the transition to a green and digital economy. Recognizing this potential, the Government of Canada published the Canadian Critical Minerals Strategy (Government of Canada, 2022). This strategy outlines a roadmap to position Canada as a leading global supplier of clean energy and technology.

The strategy paper states that economic opportunities lie all along the value chain, from exploration and extraction to processing, manufacturing and recycling. The strategy focuses on fast-tracking mining project approvals for minerals such as lithium, copper, cobalt, rare earth elements (REEs), graphite and nickel to assist with the government’s energy transition goals. To support this, Canada has allocated CAD 3.8 billion (~USD 2.8 billion, ~ EUR 2.6 billion) in federal funding in 2022 for critical mineral projects. It also prioritized six minerals- lithium, graphite, nickel, cobalt, copper, and REEs – to secure supply chains for green and digital technologies (Government of Canada, 2022). Prior to this, in 2019, the federal government launched the Mines to Mobility initiative to build a battery innovation and industrial ecosystem in Canada. This initiative has reportedly attracted significant investment, exceeding CAD 7 billion (~ USD 5.1 billion, ~ EUR 4.7 billion) attracting notable global players into segments of the domestic value chain (Government of Canada, 2022).

The major northern economies have rallied together in their efforts to diversify their sources of critical minerals away from China and its allies. In June 2022, Canada hosted several countries at the Prospectors and Developers Association of Canada Conference in Toronto, and, led by the US, established the Minerals Security Partnership (Barrera, 2022). The current members of this strategic alliance include Australia, Canada, Estonia, EU, Finland, France, Germany, India, Italy, Japan, Norway, South Korea, Sweden, the US and the UK. The partnership aims to stimulate investment into critical mineral supply chains, incentivizing market diversification. Its efforts focus on four pillars: information sharing and cooperation; investment network; elevation of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) standards; and recycling and reuse (Barrera, 2022).

China’s influence as it stands

China plays a substantial role in several critical mineral supply chains. Of 18 identified critical minerals, China is the largest producer for 12, either as a raw material or refined product (UK Government, March 2023). China is also the dominant player in manufacturing lithium-ion batteries, with three-quarters of production capacity, with companies like Panasonic and Contemporary Amperex Technology (CATL) among the top producers. In the cell manufacturing market, LG Chem, BYD Auto and Panasonic are leading players (TIPS and UNIDO, 2021). The Financial Times reported that China’s CATL and BYD Auto are expected to be the largest producers of electric batteries by 2026 (FT, 2024).

Over the last two decades, China’s involvement in Africa’s mining production has increased significantly. In 2010, Chinese companies operated in Ghana, South Africa, Zambia and Zimbabwe. Despite this, Ericsson et al argue that Chinese companies are far from taking control over African mining, given that they control less than 7% of total African mining production value (Ericsson et al., 2020). Chinese companies such as, China Moly, Zijin, Minmetals and others do hold significant stakes in some countries’ production for critical minerals like copper, cobalt and manganese. The lion’s share of African mining production, however, is still controlled by large Western transnational corporations, including Glencore and Anglo American whose combined shares account for two- thirds of total mining production (Ericcson et al., 2020; Andreoni and Roberts, 2023).

Where China does dominate is in global battery production: it accounts for about 75% of lithium-ion battery production and holds similarly high shares in the production of chemical components for batteries (Andreoni and Roberts, 2023). Linked to this is China’s emergence as a major player in the global automotive market, with estimates suggesting it has overtaken Japan as the world’s largest auto exporter in 2023. The latest data indicates that Chinese automotive exports have nearly quintupled since 2020 to almost 5 million units in 2023 (FT, 2024). BYD Auto, China’s largest EV manufacturer has played a key role in this expansion with its battery production capabilities. Having evolved from a cell phone battery maker, BYD Auto’s expertise in lithium-based battery production, the costliest component of an EV and 30-40% of the value addition, has contributed to its rise to become a world leader in the field (FT, 2024).

Box 3: China is less dominant than portrayed

Various Chinese companies control around 30% of the current African copper production; and up to 50% of the current cobalt production through their strong position in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Zambia. In the DRC, Chinese companies control 41% of cobalt production, as well as around 28% of copper in the DRC and Zambia. In Gabon, 25% of manganese production is controlled by China International Trust and Investment Corporation. In countries such as Ghana, Namibia, and South Africa, Chinese companies mainly control junior mines, and their total production is limited in comparison with the national mine production of these countries. In the case of copper production, for example, three transnational Western companies, Glencore (20%), Barrick (22%) and First Quantum (25%) controlled the bulk of Africa’s production while the total share of Chinese companies was 28% share of production.

Source: Ericsson et al., 2020; Andreoni and Roberts, 2023.

An emerging African strategy on critical minerals and the ‘just transition’

Africa is undeniably rich in critical minerals, with a large proportion of global production in both extracted and reserves of several critical minerals (See Figure 1 and Figure 2). Within this current geopolitical scenario, given the strategic role of critical minerals in the coming digital and green industrial revolution, African countries have an opportunity to leverage their resources. This can drive a process of sustainable and inclusive structural transformation, enabling them to leapfrog into adding value to their critical minerals and develop new electric batteries for new energy vehicles in Africa. In anticipation of this, the AU launched the Africa Mining Vision in 2019 to ensure that Africa strategically utilizes its mineral resources for broad-based and inclusive industrial development. This was followed by the launch of the Africa Business Forum and the African Battery Alliance in February 2021.

Click on the figures to open a zoomed-in modal view.

The governance of African minerals

The AfCFTA creates an opportunity for Africa to build a regional value chain in a range of potential sectors, such as textiles, health, and clean technologies sectors. This is supported by its rules- based framework and binds all 55 member states of the African Union (AU). While several of the eight regional economic communities (RECs) recognized by the African Union have adopted industrialization strategies and have attempted to build regional value chains, they are yet to be successful.

The governance of mineral rights and rents is central to the political economy of African countries’ mineral–energy complex. International mining companies, backed by their home governments (both politically and, in some cases, financially), orchestrate the extraction of critical minerals through complex global value chains. Bilateral agreements and international trade agreements establish the legal framework for how critical mineral rights are framed and enforced. Andreoni and Roberts (2023) identify three key factors that determine the potential developmental outcomes of Africa’s critical minerals industry:

- The degree to which governments recognize the strategic value of these critical minerals for domestic and regional industrialization and development. By integrating domestic strategies into regional industrial development plans, African countries can strengthen their bargaining position and achieve greater economies of scale and cluster development.

- The extent to which governments resist capture by specific interests and are willing and able to negotiate mineral rights terms as part of a domestic industrial policy for structural transformation. Introducing conditionalities on localization, technology sources, and complementary investments is crucial in this regard.

- The ability of governments to navigate the geopolitics of critical minerals and identify strategic global alliances that support domestic productive development. (Andreoni and Roberts, 2023).

The case and opportunity for a ‘just transition’

Africa’s strategy for critical minerals should be considered within the context of its unique ‘ just transition’ to a low carbon economy. However, the concept of the ‘ just transition’ needs a clearer definition from an African perspective. The concept originated from discussions among U.S. trade unions regarding the energy transition and has been adopted by climate activists in developing countries. However, the challenges faced by these countries extend far beyond just an energy transition. They encompass broader development challenges specific to the region, such as adaptation and resilience building (Ismail, 2022).

Furthermore, a ‘just transition’ in developing countries must address multiple systemic and structural challenges and inequities plaguing their communities. These stem from their insertion into the global economy and the unjust, imbalanced nature of its governance regimes that disadvantage developing countries. Redressing these imbalances should include reducing Africa’s commodity dependence, as well as the inequitable and asymmetrical structure of the global trade and financial architecture. In the African context, a ‘just transition’ must acknowledge that nearly 600 million people in Africa lack access to clean energy or electricity. Therefore, the ‘just transition’ for energy must prioritize developing affordable and accessible energy infrastructure.

The Fifth IPCC Assessment Report identifies climate change as a threat to sustainable development (Denton et al, 2014). The report argues that achieving climate-resilient pathways likely requires “transformational changes.” These encompass “both transformational adaptations and transformations of social processes that make such transformational adaptations feasible.” The authors define CRD as “development trajectories that combine adaptation and mitigation to realize the goal of sustainable development” (Denton et al., 2014). Thus, the concept of CRD offers a valuable framework to understand the transition underway in developing countries due to climate change (Ismail, 2022).

This definition of CRD requires mainstreaming climate change responses and integrating Nationally Determined Contributions into national development strategies, in support of the transformation of economic and social systems. CRD necessitates an ‘all of government’ approach that strengthens institutional coordination and integration through inclusive governance processes and integrates development goals with climate action (Ismail, 2022).

African countries are also able to implement the AfCFTA in a way that leverages regional integration for their transformative industrialization and transition to a low carbon economy (Ismail, 2022; 2023). To achieve this, African countries would need to adopt a ‘developmental regionalism’ approach to the AfCFTA that advances their CRD pathways, namely ‘climate resilient developmental regionalism’ (Ismail, 2022; 2023).

Implementing Climate Resilient Developmental Regionalism under the AfCFTA

This ‘climate-resilient developmental regionalism’ approach integrates climate resilience across all four pillars of the ‘developmental regionalism’ approach: adopting the principle of special and differential treatment; building regional industrial value chains; cross-border infrastructure development cooperation; and adherence to democratic governance (Ismail, 2021). To pursue ‘climate resilient developmental regionalism’ under the AfCFTA, Africa should advance the following recommendations:

- Larger African countries should take the lead in building regional renewable energy infrastructure. This effort should identify components within renewable energy technologies and infrastructure that can manufactured in Africa. A ‘just transition’ to renewables is critical, especially for countries like South Africa who are shifting away from fossil fuels. This transition must include adjustment support for workers and communities.

- African countries should collaborate to build regional climate-resilient infrastructure, like water supply, and climate-smart agriculture, to facilitate adaptation to climate change.

- African countries must maintain momentum in building ambitious regional value chains across priority sectors. These sectors include critical minerals, electric batteries and new energy vehicles, automotive assembly and components, and the digital economy. In each sector, African countries should embrace new sustainable technologies aligned with the ‘Sustainability shift’ driving consumption patterns in Western markets, like the EU and US. This will propel green industrialization efforts.

- Building mutually beneficial strategic partnerships with developed countries is crucial for African countries. A significant opportunity lies in building a partnership between OECD countries, particularly the EU, US and UK, and the AfCFTA Secretariat. This partnership can focus on building regional value chains for critical minerals, electric batteries, and new energy vehicles, and supporting AfCFTA implementation to advance Africa’s ‘climate-resilient developmental regionalism’ (Ismail, 2023).

- The AfCFTA Secretariat can play a critical coordinating role across these strategic programs. It can facilitate negotiations between the member states and assist them in cooperating to build cross-border continental regional energy transmission and distribution channels. To advance this process, a research and dialogue program is needed that engages governments, private sector investors, and regulatory bodies at both national and regional levels.

- The AfCFTA Secretariat must spearhead a continent-wide process of building regional value chains across and between the existing RECs. Several RECs (IGAD, CEN-SAD, AMU) have made minimal progress on regional trade and economic integration. The main reasons for this limited progress are the lack of productive capacity within the member states and the underdeveloped state of regional value chains. An AfCFTA-led process should leverage the competitive advantages of different countries and prioritize building strong regional value chains.

- The AfCFTA and the AU should jointly lead efforts to build capacity on African perspectives and narratives, along with technical expertise on key trade and industrial transformation issues. This capacity and expertise should be institutionalized within African universities, agencies, RECs and think tanks, and courses could be offered to African policymakers and stakeholders, through the proposed AfCFTA Academy. The RECs would also be valuable partners, serving as delivery mechanisms. These capacity-building programs should also share knowledge on innovative approaches to regional integration, drawing from research and expertise of other relevant regional integration projects like Mercusor, Association of Southeast Asian Nations and the EU.

References

Andreoni, A., & Roberts, S. (2023). Geopolitics of critical minerals renewable energy supply chains. African Climate Foundation. https://africanclimatefoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/800644-ACF-03_Geopolitics-of-critical-minerals-R_WEB.pdf

Barrera, P. (2022, June 15). US, Canada and other countries join forces to secure minerals. Investing News. https://investingnews.com/us-canada-secure-critical-minerals/

Davies, R. (2023). Navigating new turbulences at the nexus of trade and climate change. African Climate Foundation. https://africanclimatefoundation.org/news_and_analysis/navigating-new-turbulences-at-the-nexus-of-trade-and-climate-change/

Denton, F., Wilbanks, T. J., Abeysinghe, A. C., Burton, I., Gao, Q., Lemos, M. C., Masui, T., O'Brien, K. L., & Warner, K. (2014). Climate-resilient pathways: Adaptation, mitigation, and sustainable development. In C. B. Field, V. R. Barros, D. J. Dokken, K. J. Mach, M. D. Mastrandrea, T. E. Bilir, M. Chatterjee, K. L. Ebi, Y. O. Estrada, R. C. Genova, B. Girma, E. S. Kissel, A. N. Levy, S. MacCracken, P. R. Mastrandrea, & L. L. White (Eds.), Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (pp. 1101-1131). Cambridge University Press. https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/02/WGIIAR5-Chap20_FINAL.pdf

Department of Trade Industry and Competition of South Africa. (2021). First input towards the development of the auto green paper on the advancement of new energy vehicles in South Africa. http://www.thedtic.gov.za/wp-content/uploads/EV_Green_Paper.pdf

Fakude, N. (2023). African critical minerals summit, November 2023, South Africa critical minerals. Minerals Council of South Africa. https://www.mineralscouncil.org.za/downloads/send/7-latest-presentation/2076-african-critical-minerals-summit-29-august-2023

Financial Times. (2024, January 5). China's electric vehicle dominance presents a challenge to the West. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/de696ddb-2201-4830-848b-6301b64ad0e5

Franco-German Council of Economic Experts. (2023). The Inflation Reduction Act: How should the EU react? https://www.bmwk.de/Redaktion/DE/Downloads/I/inflation-reduction-act-how-should-eu-react.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=2

Gabor, D., Fertik, T., & Sahay, T. (2023). Bidenomics [Audio podcast]. https://thedig.blubrry.net/podcast/bidenomics-w-daniela-gabor-ted-fertik-tim-sahay/

Government of Canada. (2022). The Canadian critical minerals strategy: From exploration to recycling: Powering the green and digital economy for Canada and the world. https://www.canada.ca/en/campaign/critical-minerals-in-canada/canadian-critical-minerals-strategy.html

Henley, J., & Rankin, J. (2023). Can EU anger at Biden's 'protectionist' green deal translate into effective action? The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/jan/18/eu-anger-biden-green-370bn-deal-action-industrial-policy

IPCC. (2022). Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press. https://report.ipcc.ch/ar6/wg2/IPCC_AR6_WGII_FullReport.pdf

Ismail, F. (2023). Beyond the just energy transition narrative: How South Africa can support the AfCFTA to advance climate resilient development. South African Journal of International Affairs, 30(2), 245-262. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10220461.2023.2228317

Ismail, F. (2022). Trade and climate resilient development in Africa: Towards a global green new deal. Forum on Trade, Environment and the SDGs (TESS). https://tessforum.org/latest/trade-and-climate-resilient-development-in-africa-towards-a-global-green-new-deal

Ismail, F. (2021). The AfCFTA and developmental regionalism: A handbook. Trade & Industrial Policy Strategies. http://www.tips.org.za/research-archive/books/item/4121-the-african-continental-free-trade-area-afcfta-and-developmental-regionalism-a-handbook

Jensen, F., & Whitfield, L. (2022). Leveraging participation in apparel global supply chains through green industrialization strategies: Implications for low-income countries. Ecological Economics, 194.

Kaare, P., & Medinilla, A. (2023). Green industrialization: Leveraging critical raw materials for an African battery value chain. European Centre for Development Policy Management (ECDPM). https://ecdpm.org/work/african-battery-value-chain-kickstart-green-industrialisation

Montmasson-Clair, G., Moshikaro, L., & Monaisa, L. (2021). Opportunities to develop the lithium-ion battery value chain in South Africa. Trade and Industrial Policy Strategies. https://www.tips.org.za/policy-briefs/item/4013-opportunities-to-development-the-lithium-ion-battery-value-chain-in-south-africa

NAAMSA. (2023). South Africa's new energy vehicle transitional roadmap: The route to the white paper. https://www.tips.org.za/research-archive/sustainable-growth/green-economy-2

National Research Council. (2007). Minerals, critical minerals, and the U.S. economy. National Academy of Sciences.

Ruto, W. (2023, September 4). Remarks by His Excellency Dr William Ruto, PhD, CGH, President of the Republic of Kenya, at the opening of the Africa Climate Summit Ministerial Conference. https://www.president.go.ke/wp-content/uploads/AT-THE-OPENING-OF-THE-AFRICA-CLIMATE-SUMMIT-MINISTERIAL-CONFERENCE.pdf

SADC. (2015). SADC industrialization strategy and roadmap. https://www.sadc.int/document/sadc-industrialisation-strategy-and-roadmap-english

TIPS and UNIDO. (2021). Opportunities to develop lithium-ion battery value chain in South Africa. https://www.tips.org.za/images/Battery_Manufacturing_value_chain_study.pdf

UK Government. (2020). Ten point plan for a green revolution. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-ten-point-plan-for-a-green-industrial-revolution

UK Government. (2023). Resilience for the future: The UK's critical minerals strategy. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/uk-critical-mineral-strategy

UNCTAD. (2023). State of commodity dependence 2023. https://unctad.org/publication/state-commodity-dependence-2023

US Department of Energy. (2021). Critical minerals and materials (2021 to 2031). https://www.energy.gov/sites/default/files/2021/01/f82/DOE%20Critical%20Minerals%20and%20Materials%20Strategy_0.pdf

USGS. (2022, February 22). US Geological Survey releases 2022 list of critical minerals. https://www.usgs.gov/news/national-news-release/us-geological-survey-releases-2022-list-critical-minerals

World Economic Forum. (2023, January 22). We're on the brink of a policrisis – how worried should we be? https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2023/01/polycrisis-global-risks-report-cost-of-living/