Executive Summary

Senegal is one of the African countries considered most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. These impacts affect key sectors of economic production such as agriculture, livestock, fisheries, tourism, and infrastructure, as well as those relating to human and social capital such as education, housing, health, and well-being. However, despite Senegal’s efforts to take decisive climate actions, it faces several barriers and gaps regarding access to endogenous knowledge, capacity building, and financing. This access is deemed vital for the integration of the needs of communities in terms of locally-led adaptation (LLA) and meeting the country’s stated goals for its Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs).

From May 2022 to December 2023, the Africa Policy Research Institute (APRI), in close collaboration with ENDA-Energy and a range of diverse stakeholders such as scientists, policymakers, practitioners, and local communities, implemented a research project on locally-led adaptation to understand, document, and communicate potential gaps, challenges, opportunities, and entry points related to the integration of endogenous practices into national climate actions. Activities involved an assessment to probe the alignment of endogenous adaptation practices with adaptation options of the NDC and other climate action policies and strategies. Additionally, the research sought to understand and document local adaptation actions by conducting three deep dives on locally-led adaptation in agriculture, coastal zones, and health sectors.

Overall, the results show that the country achieved appreciable progress in climate action despite the weak access to finance resources and the low capacity to sufficiently domesticate climate policies at the local level. Moreover, the main findings and key messages from the three case studies on priority adaptation sectors of agriculture in Daga Birame, coastal zones in Dionewar, and Widou Thiéngoly health areas highlight the relevance, the value added, and the challenges related to locally-led adaptation for the NDC.

Overall results show that:

- Endogenous adaptation practices implemented with the support of technical services, civil society, and non-governmental organizations (NGO) are well aligned with the priority options of the NDCs as well as other national policies and strategies designed to deal with the impacts of climate change. However, their contribution is not recognized by the central government in terms of climate action and governance. In fact, the adaptation practices and strategies implemented by local communities appear neither in the climate action monitoring and evaluation system nor in national communications on climate change.

- Locally-led adaptation practices contribute to climate adaptation, community resilience, and support for livelihood opportunities and general wellbeing.

- The sectorial and territorial approach promoted by the country to implement NDCs does not adequately integrate the needs of communities in terms of locally-led adaptation, making it difficult for local communities to initiate and sustain effective and long-term action.

- These findings demonstrate that locally-led adaptation has enormous potential for transformative climate action, sustainable development, and resilience-building beyond the local level.

Based on these findings, the author offers the following five recommendations on how to enhance opportunities for integrating locally-led adaptation in climate action.

For national and local policymakers and other actors:

- Decentralize and develop climate governance and institutions at the national and local level: Climate governance stakeholders must recognize the importance and added value of locally-led adaptation and encourage the integration of communities' endogenous adaptation practices into the various priority adaptation options of the NDC for greater efficiency, performance, and impact in climate action in Senegal.

- Encourage and support collaborations between research institutions, policymakers, civil society organizations, and local communities: This collaboration is critical to ensure that all relevant stakeholders are included in the identification, documentation, and communication of relevant local adaptation experiences. This knowledge is instrumental in shaping decision-making and implementation processes of the NDCs and other national and local development policies and strategies.

- Invest to remove barriers related to technical capacity building and climate finance access for local communities: To successfully integrate locally-led adaptation into climate action planning in Senegal and improve synergy between adaptation options in the NDC and endogenous adaptation practices that are already well aligned, the government needs to invest heavily in building the local human and technical capacity of stakeholders and should actively seek innovative climate finance to support, and, where appropriate, scale LLA. This also requires the mobilization of domestic resources to sustain climate actions in the long term.

For the international community:

- Promote the integration of locally-led adaptation action into the implementation of national and global climate goals: Community adaptation strategies and solutions bring added value in enhancing the health and well-being of local communities. They are therefore aligned with the priority adaptation options of the NDCs and other national policies. With this in mind, the international community, through the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and other bilateral and multilateral development cooperation agencies, should recommend and encourage countries and their international partners to place LLA adaptation centrally within their financial support and implementation processes.

- Adapt proactive and innovative ways to finance and ensure access to local-level actors: Climate facilities such as the Green Climate Fund (GCF), the Adaptation Fund (AF), and the Global Environment Facility (GEF) must, in unison with bilateral development agencies, set up a common fund exclusively reserved for financing local adaptation initiatives directly led by communities. This will make endogenous practices more sustainable and increase the value and efficiency of climate finance.

1. Background and Context

1.1. Introduction

Senegal is a country of 196,722 km2 located at the western extremity of the African continent. Its Sudano-Sahelian climate is tropical in the south and semi-desert in the north, with a dry season from November to June and a hot, humid season from June to October. Senegal is among the African countries considered to be highly exposed and vulnerable to the impacts of climate change due to its location in the Sahelian zone and in a wide coastal strip.1 Exposure to climate risks depends on the variability of key parameters such as rainfall, temperature, sea level, and the occurrence of extreme hydro-meteorological events that will determine current and future climate characteristics.

1.2 Status of climate change impacts and actions

Climate change is emerging as a critical development issue in Senegal, increasingly featuring in national discussions and political debates. The deterioration of the productive bases of the national economy – in particular agriculture, livestock, and fisheries, which employ a significant proportion of the working population, especially in rural areas – illustrates the economic challenges of climate change in Senegal.2 These challenges explain why progress is still slow and the need for adaptation remains so significant.

The trend towards higher temperatures and disruption of the rainfall regime, often punctuated by extreme events that have become frequent, are generating growing climate risks linked to the frequency of hazards, impacts, and vulnerabilities that expose and render fragile the foundations of the national economy and natural and human capital.3

Within a context of widespread socio-economic poverty and low human development, the risks posed by the high probability of occurrences of present and future hazards pose serious threats to the main factors of production contributing to human and social capital in Senegal.4 Thus, such is the urgency of climate action in favor of vulnerable territories that a locally-led adaptation approach is becoming increasingly necessary.

Like all countries committed to climate action, in December 2020 Senegal validated its NDC, which includes priority adaptation options set out in the framework of National Sectoral Adaptation Plans (NAPs), finalized in august 2023. The NDC should provide more integrated, effective, efficient and sustainable responses to climate challenges.5 The process of developing sectorial NAPs for agriculture, flooding, infrastructure, health, and coastal zones has been completed, and the priority adaptation options have been set out in the form of climate resilience projects and programs that the Government of Senegal and its technical and financial partners have pledged to support. However, the effective implementation of these policies is yet to materialize.

1.3. Identified gaps and opportunities

The analysis of the implementation process of climate action and adaptation policies in Senegal highlights a certain number of gaps and barriers related to: i) poor integration of climate risks in the planning of sectoral development policies; ii) inequalities in access to climate financing between priority adaptation sectors and vulnerable territories; iii) the weakness of technical and scientific capacity to transfer and take ownership of innovative adaptation strategies with a high impact on communities; iv) the low consideration of communities’ and local actors’ adaptation needs; and v) the lack of a framework to monitor and evaluate performance in climate policies implementation, such as the Monitoring, Reporting, Verifying (MRV) system.

However, these gaps can be addressed within climate action opportunities at local, national, and international levels related to: i) the existence of relevant local initiatives and experiences in adaptation practices and strategies implemented by vulnerable communities; ii) the integration of the climate change dimension in the national economy and social policies as well as the sectoral and territorial development plans; iii) the availability of international financial mechanisms to support the implementation of climate adaptation projects and programs; and iv) the availability of scientific evidence demonstrating climate additionality and accountability in production systems and other social sectors.

1.4. Key rationale and key objectives

With the support and close collaboration of ENDA-Energy, APRI implemented the ‘Climate Adaptation: Strategies, Initiatives, and Practices’ research project from May of 2022 to December of 2023. The project aimed to examine progress and policy implementation gaps to better understand and document existing challenges and opportunities for advancing climate solutions that are focused on country-specific priorities and needs and are consistent with endogenous adaptation practices.

1.5. Approach and methodology behind the study

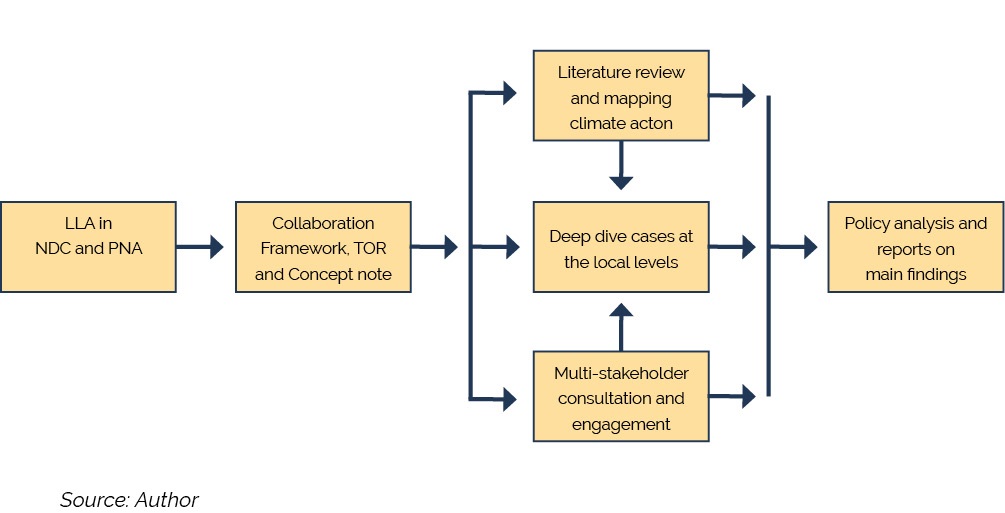

The research project adopted a qualitative approach and employed multiple research methods including:

- an extensive review of literature and relevant climate change documents on NDC, NAP, adaptation policies, national and local development policy planning, climate governance, locally led adaptation, etc. This was first carried out to understand the level of progress on climate change adaptation in the country;

- mapping of NDC as well as other national policies, strategies, and initiatives, including the assessment of adaptation coverage, the alignment of local adaptation policies with the country’s needs, priorities, and international development goals and commitments, and the state of financing. This exercise also included the mapping of stakeholders in the adaptation space;

- the consultation of stakeholders at different scales and categories of actors (National Climate Change Committee, academic institutions, technical supporting services, non-governmental agencies, civil society and community representatives, private sector, etc.). This enabled the mapping of policies, strategies, and stakeholders using an interview guide that allowed for the collection of information on the state of climate action, gaps, shortcomings, and needs of actors for a better integration of locally-led adaptation into climate policies at the national and territorial level;

- deep dives of three case studies on local adaptation actions according to key priority adaptation sectors including: the climate smart village of Daga Birame in food security (agriculture sector), the REVARD project of Dionewar island in coastal erosion control (coastal zones sector), and the Early Warning System (EWS) initiative of Widou Thiéngoly in heat waves health impacts mitigation (health sector).

Figure 1: Overview of research approach (Source: Author)

2. Mapping the Adaptation Policy and Stakeholder Landscape

2.1 Adaptation components of the NDCs

To improve the performance and effectiveness of economic and social development policies within the Emerging Senegal Plan (Plan Sénégal Émergent, or PSE) for 2035, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the 2030 Agenda, and the National Determined Contribution (NDC), the government of Senegal has initiated the implementation of a strategic plan which integrates the need to consider adaptation in the planning of economic and social development policies, thereby increasing the resilience of the country's production systems to climate change impacts.6 As part of the country's development strategy (the Emerging Senegal Plan for the period 2014-2035), the NDC includes priority adaptation options that are developed within the framework of NAPs addressing key priority vulnerable sectors including agriculture, livestock, fisheries, health, water resources and floods, biodiversity, and the coastal zone.7

The table below summarizes the targeted adaptation measures according to the priority sectors defined by Senegal.

| Sector | Priority adaptation measures |

|---|---|

| Sector | Priority adaptation measures |

| Agriculture |

|

| Livestock |

|

| Fishing |

|

| Coastal Areas |

|

| Resources in Water |

|

| Biodiversity |

|

| Health |

|

| Social Sector/Floods |

|

Table 1: Targeted adaptation measures according to the priority sectors defined (Source: The Emerging senegal Plan)

The sectors identified as priorities in the NDC framework are currently preparing their national sectoral adaptation plans. These will be implemented according to a program and project approach requiring the mobilization of skills and funding.

2.2 Other national adaptation policies and strategies

In addition to the NDC, the government of Senegal has assembled a development strategy known as the Emerging Senegal Plan (PSE) for the period up to 2035. This plan is well aligned with both the sustainable development goals (SDGs) of the 2030 Agenda and the NDC.8 The PSE emphasizes the need to consider adaptation in the planning of economic and social development policies to increase the resilience of the country's production systems to climate change impacts. With the need to incorporate the NDC’s unconditional commitments related to climate change adaptation into national medium- and long-term budgetary programing, the State of Senegal is progressing towards an integrated approach to climate action by harmonizing the frameworks of various national policies’ implementation plans, linking Sectoral Development Policy Letters (LPSD), Multiannual Expenditure Programming Documents (DPPD), Communal Development Plans (PDC), Departmental Development Plans (PDD), etc. This integration ensures better articulation, alignment, and coherence of adaptation options with sustainable development objectives and economic and social development goals.9

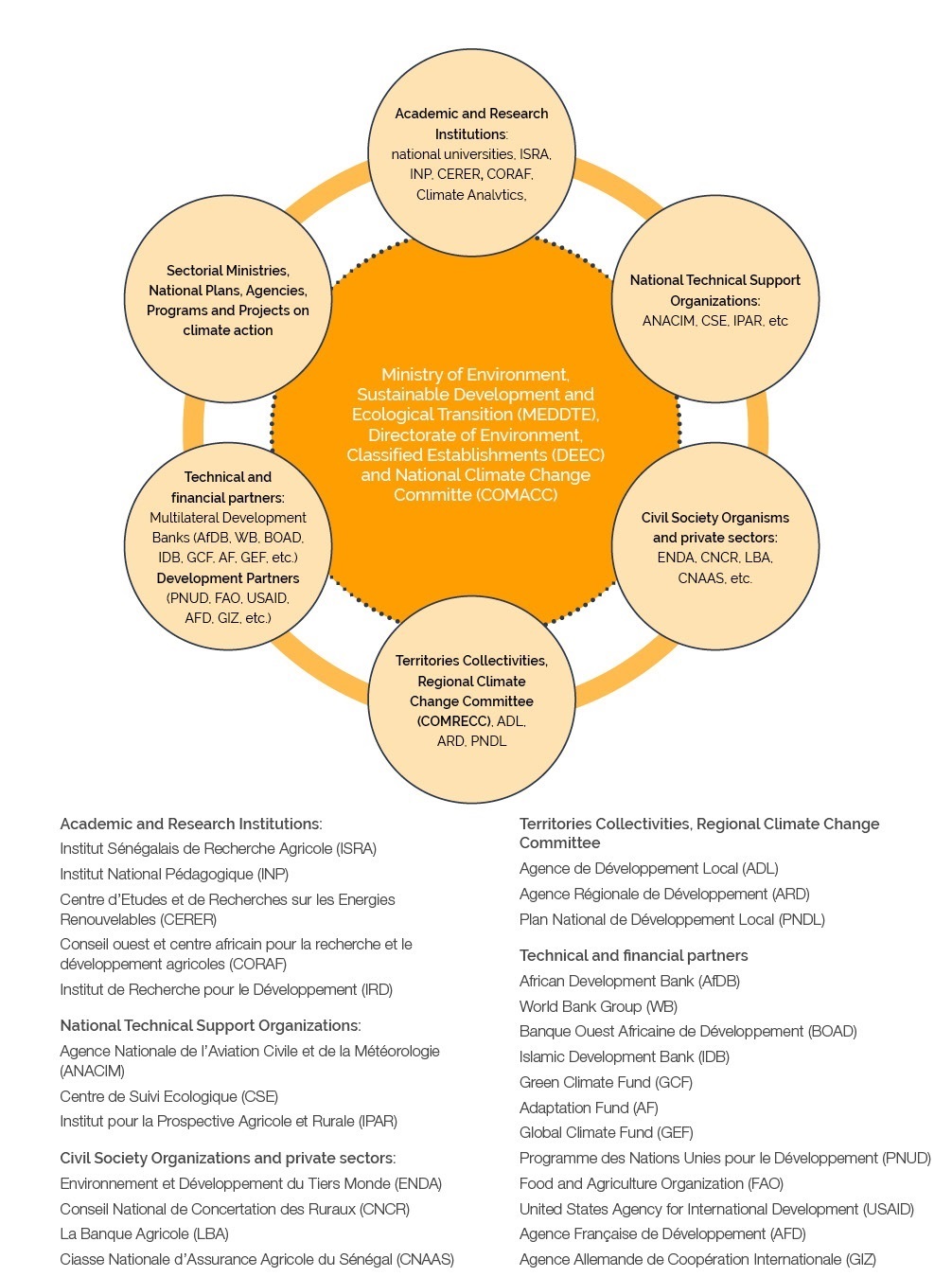

2.3. Stakeholders in the space

An analysis of the adaptation sector in Senegal shows that a diversity of stakeholders with different areas of expertise are involved in climate action.10 The mapping of these different actors showed that stakeholders fall into seven major categories as summarized in Table 2 and Figure 2 below.

| Category of actors | Institutions concerned | Rules and responsibilities |

|---|---|---|

| National strategic authorities of climate action and adaptation policies implementation | Directorate of Environment and Classified Establishments (DEEC), National Climate Change Committee (COMNACC) | This category of stakeholders coordinates the planning and implementation and monitors the climate change policies and programs at the highest level. |

| Priority adaptation sectors leading Sectorial National Adaptation Plan (NAP) | Ministries of the nine priority adaptation sectors: agriculture, livestock, coastal zones, biodiversity, water resources, health, social sector/floods, fisheries, infrastructures | This category of stakeholders implements and coordinates climate adaptation policies for priority sectors defined in NDC and NAP. |

| National technical support organizations | National Agency for Civil Aviation and Meteorology (ANACIM), Centre for Ecological Monitoring (CSE), Agricultural and Rural Foresight Initiative (IPAR) | This category of actors gives technical support on knowledge management, climate data and services access, capacity building training, projects development and funds mobilization. |

| Academic and research institutions | National Universities, Senegalese Institute of Agricultural Research (ISRA), National Pedological Institute (INP), Centre for Studies and Research on Renewable Energies (CERER), West and Central African Council for Agricultural Research(CORAF), Climate Analytics, Development Research Institute (IRD), etc. | This category of actors supports the process to move from science development to science implementation (translation of scientific theory into action), addressing impacts of climate change research and capacity-building for vulnerable communities and priority sectors for climate action. |

| International agencies and technical and financial partners supporting climate action and adaptation policies | Multilateral development banks (World Bank Group, African Development Bank, Islamic Development Bank, West Africa Development Bank), Climate change facilities (Global Environment Fund, Green Climate Fund, Adaptation Fund, African Climate Change Fund), bilateral agencies and partners (PNUD, FAO, USAID, AFD, GIZ, Lux-Dev, etc.) | This category of stakeholders supports resource mobilization, capacity development and technology development and transfer for current and future adaptation actions. |

| Organizations of civil society and private sector National facilitating climate adaptation implementation | Enda Energy, National Rural Dialogue Framework (CNCR), Agricultural Bank (LBA), National Agricultural Insurance Fund of Senegal (CNAAS), National Civil Engineering Companies | This category of stakeholders develops actions in social mobilization and organization of actors on climate action, and engages people in planning, advocacy, education, and awareness raising at the local level. |

| Local governments and actors supporting field climate adaptation implementation | Councils or Assemblies of territories collectivities, Regional Climate Change Committee (COMRECC), Local Development Agency (ADL), Regional Development Agency (ARD), National Local Development Plan (PNDL) | This category of actors is involved in planning and implementation of several climate change policies, programs, and projects at the local and community level. |

Table 2: Stakeholders mapping and organization for climate governance in Senegal

Figure 2: National climate action stakeholder mapping and organization in Senegal (Source: Author)

As highlighted by the climate action landscape, Senegal has made suitable progress in formulating various policies, strategies, and frameworks to guide climate change actions. These policies offer a structured approach, highlighting priority sectors and adaptation measures to enhance resilience and protect vulnerable populations from climate change. Nevertheless, effective and sustained implementation of the updated NDC published in 2020 demands:multi- and inter-sectoral approaches, improved consultation among stakeholders, reinforced technical and human resources, citizen- and decision-maker-focused communication, clear definition of needs and priorities, and a long-term strategy addressing loss and damages. Additionally, it is crucial to address uncertainties in mobilizing the $14.5 billion in climate funds required in order to implement the NDC by 2030. This includes devolving funds for communities to enact local adaptation strategies and practices while enhancing climate governance models.

3. Locally-led Adaptation Practices, Strategies, and Actions

In addition to the national adaptation policies, communities have developed several strategies, initiatives, and practices according to their level of knowledge, the adaptation option, and opportunities available. Engagement with diverse stakeholders shows that locally led adaptation practices are recognized as an essential pathway for the implementation of NDC goals in Senegal. Furthermore, there is general recognition that local communities have the best understanding of their contexts and socio-economic conditions and are therefore better positioned to identify and implement effective adaptation strategies according to their knowledge in climate change. This section highlights key findings from three case studies that were undertaken to explore the motivation, strategies, and outcomes of local adaptation actions as well as the associated challenges, opportunities, and entry points for enhanced and sustained adaptation actions.

3.1. Daga Birame locally-led adaptation experience in agriculture resilience

The local adaptation initiative of women farmers in the climate-smart village of Daga Birame is located in the department of Kaffrine. It is an example of the country’s NDC agriculture priority sector being implemented by the local community, scientists from ISRA, and technical development services composed of ANACIM, ANCAR, DA, and DRDR. The communities are motivated by the need to improve agricultural yield, living conditions, and well-being. The actions are mainly related to capacity building of farmers in climate resilience, such as the use of climate information services and the delivery of technical and financial support to communities to ensure sustainability in climate change adaptation. Thus, the actions facilitate the development of climate-conscious agricultural practices and index-based agricultural insurance for risk management. The actions have resulted in a number of positive impacts, such as improved resilience of community agricultural systems, better living and livelihood conditions, and the improved health and well-being of beneficiaries due to an increase in agricultural yields. Co-benefits include promotion of solar energy (renewable energy) to power homes and the supply of borehole water for domestic and agricultural use, thereby strengthening the food security, nutritional status, and health of community members.

Figure 3: Practices and adaptation strategies from Daga Birame smart climate village (A) placard for the community plot for the domestication of forest fruit trees ; (B) placard for community plot and cultural agriculture system utilizing adaptation measures ; (C) use of solar energy; (D) man holding improved yield after adaptions measure were put in place in right hand and original yield without adaptation measures in left hand. (Source: Author)

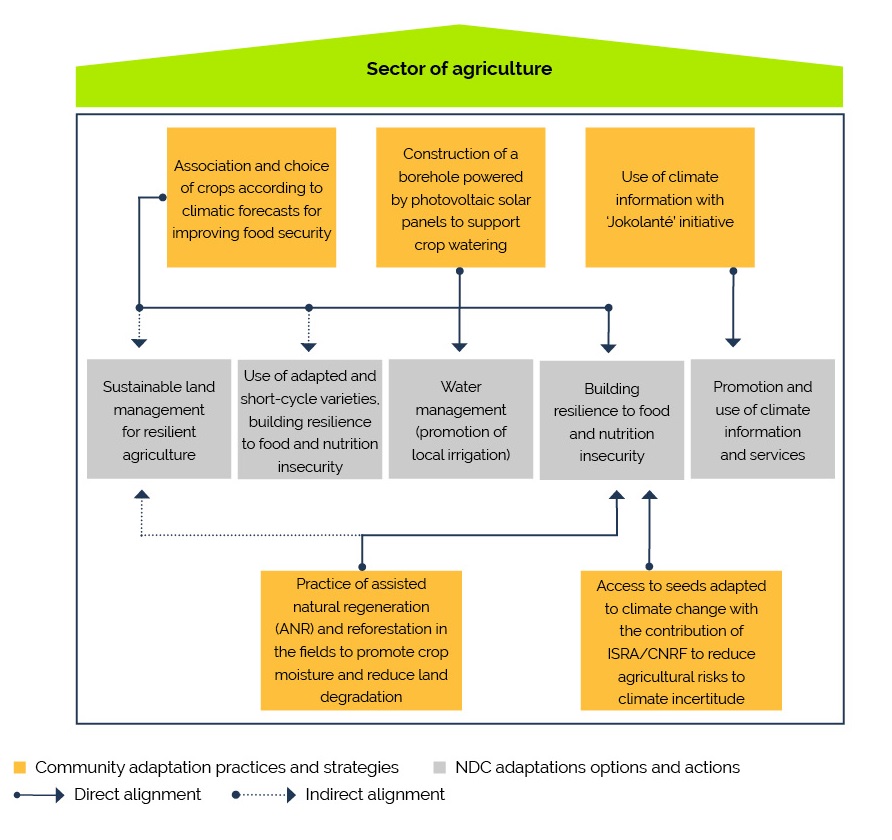

Alignment with NDCs and other national/regional/local policy priorities

The practices and strategies from Daga Birame village farming communities are aligned with and connected to the national adaptation actions of NDC, especially in the agriculture priority sector, as shown in the figure below. Additionally, these community initiatives are in harmony with various programs, SDGs, national agriculture development plans, and local development plans (PDC, PDD).

Figure 4: Alignment between local community adaptation strategies from Daga Birame and NDC adaptation options for the agriculture sector. (Source: Author)

Despite the evident alignment of community initiatives with national policies, the participants in these activities were often unaware of the provisions in NDCs and other national climate and sustainable development policies, and their potential contributions to effective implementation. This lack of policy awareness at the local level is indicative of a predominant national approach to climate policy development and implementation. Moreover, the absence of central government support to ensure the sustainability of the Daga Birame initiative, coupled with limited access to technical capacities and climate financing, presents substantial barriers to the effectiveness and long-term viability of community adaptation practices, strategies, and actions in the agricultural sector.

3.2. Dionewar Island locally-led adaptation experience in coastal erosion resilience

REVARD (Reducing Vulnerability and Improving Resilience of Dionewar's Coastal Communities) is a local adaptation initiative located on the island of Dionewar in central-western Senegal. It is a project from the coastal zones priority sector, and is based on the use of the Epis Maltais Savard system, implemented with the support of the CSE in collaboration with the Association for the Development of Dionewar (ADD), the Adaptation Fund (AF), the Nébéday Association, the Delegation of the European Union in Senegal, the Protected Marine Areas (AMP), the Ecole 2 de Dionewar, and the local populations. Communities are motivated by the need to support key livelihood activities such as fishing, living conditions, and well-being. The primary activities undertaken include: the establishment of protective structures such as piles, dikes and bunds; the implementation and monitoring of Maltese groins as a soft method to slow down the rate of coastal erosion; the development of reforestation activities with local species to reduce coastal erosion; and the establishment of early warning systems for disaster risk management such as flags and telephone messages to fishermen. The significant outcomes include the reconstitution of the beach with a gain of 2.6 meters, and, as a result of better access to climate information, the risk reduction of fishing-related disasters . Reported and observed co-benefits include strengthened food security, improved nutritional and health status, and sustained and secure incomes for the fishing community.

Figure 5: Practices and adaptation strategies from Dinewar island community (A) protective structure; (B) protective structure; (C) Maltese groin to slow down the rate of coastal erosion; (D) Maltese groin to slow down the rate of coastal erosion. (Source: Author)

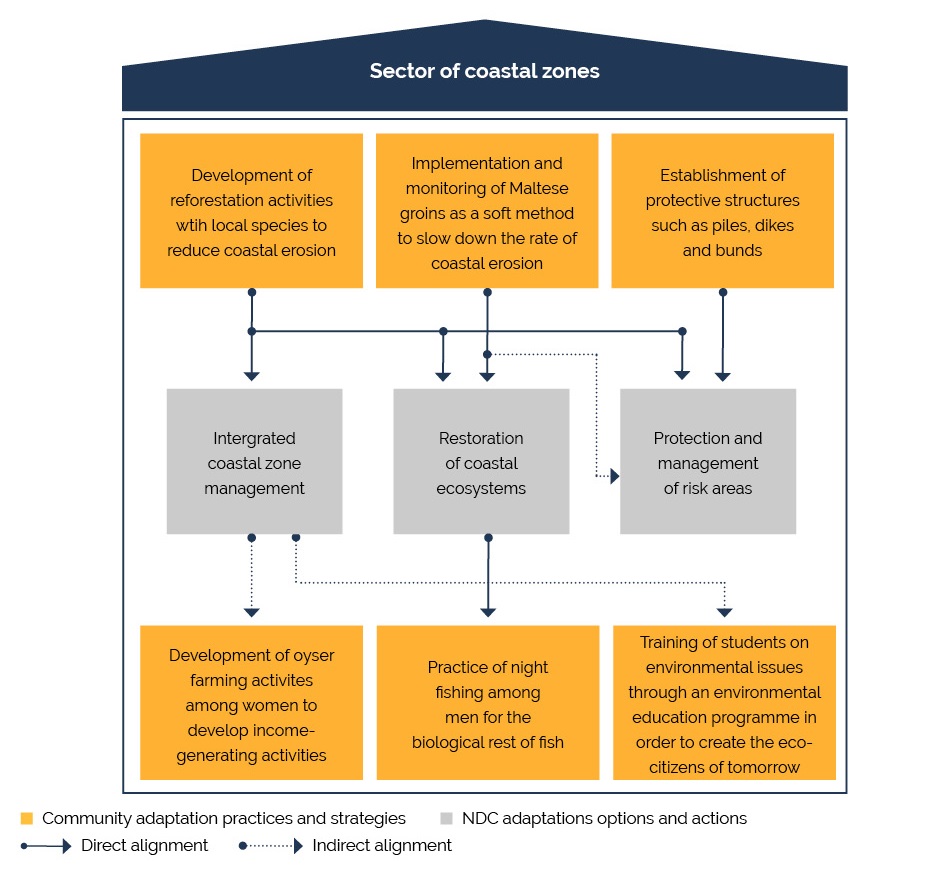

Alignment with NDCs and other national/regional/local policy priorities

As shown in Figure 6 below, the island community of Dionewar has developed several practices and strategies that are aligned with or connected to the national adaptation options and actions of the NDC coastal zones sector. Community practices and strategies are also well aligned with several other initiatives in coastal erosion management (WACA) and local development plans. However, the potential for locally led adaptation, like that demonstrated by the Dionewar community, to fully contribute to Senegal’s ambitious climate goals remains limited due to the central government’s low consideration of endogenous practices and a lack of knowledge about added value, capacity building, and climate financing. Yet the case underscores that existing locally-led adaptation initiatives not only offer opportunities for the implementation of NDCs, but also for other initiatives aimed at combating coastal erosion in Senegal, such as the National Adaptation Plan (NAP). These efforts have complementary effects on the well-being and livelihoods of Senegalese citizens, extending well beyond the boundaries of the Dionewar community.

Figure 6: Alignment between local community adaptation strategies from Dionewar and NDC adaptation options for coastal zones sector. (Source: Author)

3.3 Widou Thiéngoly Island locally-led adaptation experience in health resilience

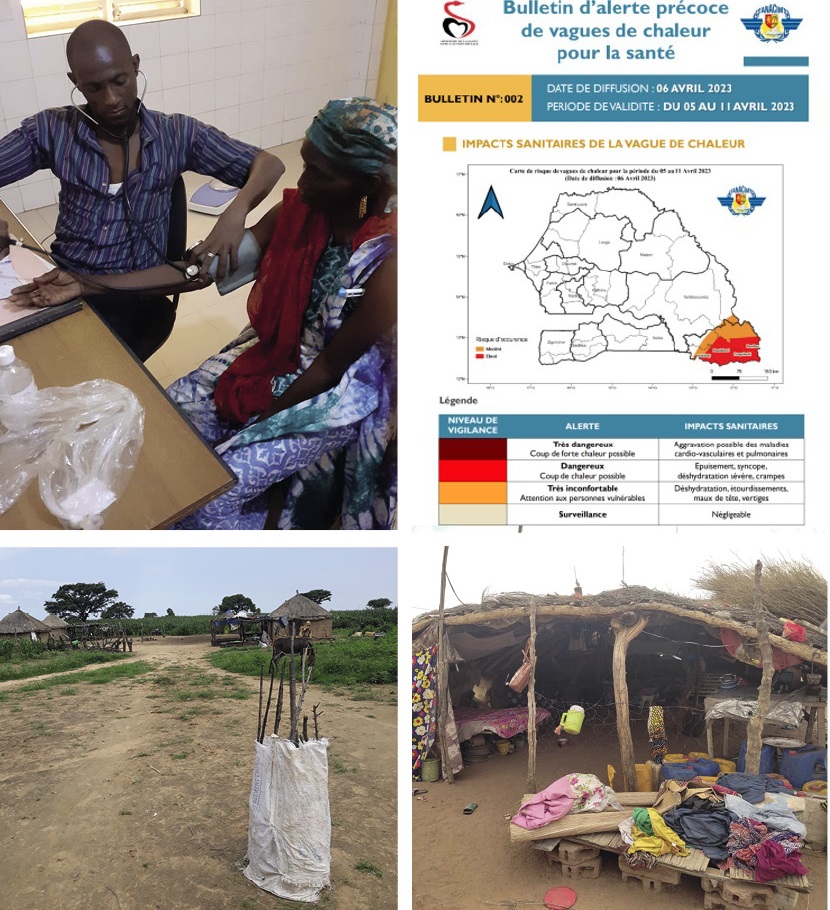

The village of Widou Thiengoly is located in the commune of Téssékéré in the heart of the silvopastoral zone. It has a semi-arid tropical climate with a long dry season from October to June, characterized by temperatures as high as 46 to 48°C. The local community adaptation initiative in resilience to the health impacts of heat waves is based on the Early Warning System (EWS) and is related to the priority health sector of the country NDC. This initiative is implemented by the community in collaboration with the Ministry of Health and Social Action (MSAS), the National Agency for Civil Aviation and Meteorology (ANACIM), the Centre for Ecological Monitoring (CSE), the Directorate of Civil Protection (DPC), the Senegalese National Red Cross (CRNS), the Great Green Wall Agency (AGMV), the Health Development Committee (CDS), and the Association of Borehole Users (ASUFOR). The main actions achieved include the implementation of an early warning system, reforestation actions in public spaces to mitigate the effects of heat and air pollution, the promotion of the construction of heat-adapted habitats (bioclimatic architecture) with low carbon buildings, and free medical consultations to reduce the health risks linked to heat waves. These outcomes have enabled the population to adapt to climate change and increase their resilience to health risks. Reported and observed co-benefits included reduced health costs for households, reduction of climate-sensitive diseases, and general improvements in the productivity, health, and well-being of the community.

Figure 7: Local community adaptation practices to health risks resilience in Widou Thiéngoly (A) free consultation campaign for local populations; (B) early warning system bulletin weekly shared with end users during heatwave events; (C) reforestation to mitigate the impact of the heat and type of shelters; and (D) habitats used during heatwave episodes. (Source: Author)

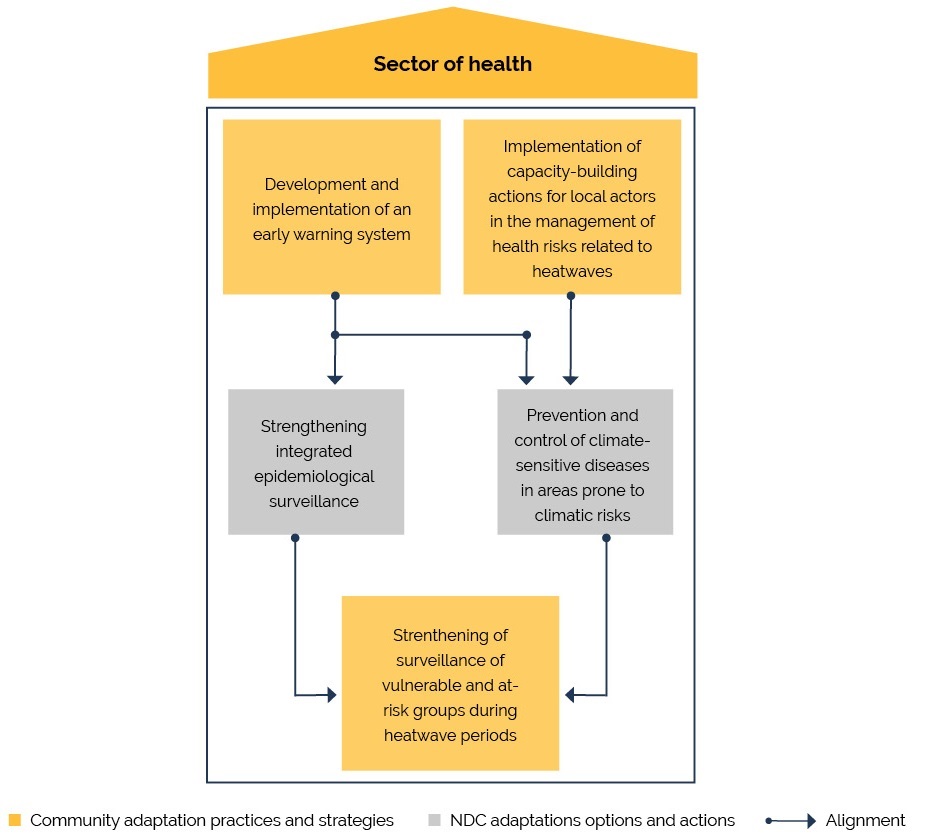

Alignment with NDCs and other national/regional/local policy priorities

As demonstrated in Figure 8 below, actions of the island community of Widou Thiéngoly to combat health risks due to climate change impacts are well aligned with the key adaptation options of the NDC’s health sector. Community practices and strategies are also well aligned with other initiatives in health system resilience such as the National Health and Social Development plan (PNDSS-2019-2028) and the Health Community Development Plan (PCDS-2018).

However, the central government's limited recognition of local practices, alongside the absence of scientific evidence, capacity-building, and climate financing, hinder sustainable implementation in the Widou Thiéngoly community. These challenges, similar to those in agriculture, impede effective health risk management and long-term resilience.

Figure 8: Alignment between local community adaptation strategies from Widou Thiéngoly and NDC adaptation options for health sector. (Source: Author)

Despite limited central government support, community initiatives actively contribute to achieving NDC and national climate and sustainable development objectives, focusing on agriculture, coastal zones, and health. These local adaptations offer tailored solutions that align with the specific socio-economic and cultural needs of communities, motivating collective efforts and ensuring long-term sustainability. This empowerment enables communities to address climate change vulnerabilities, enhancing resilience. Importantly, these initiatives make substantial contributions to climate and adaptation efforts at local, national, and international levels.

4. Recommendations for Effective and Sustainable Locally-Led Climate Adaptation in Senegal

Locally-led adaptation strategies are essential for ensuring that the most vulnerable communities are not left behind and have a say in decisions that affect their lives.11 Local people and communities most often affected and impacted by climate change are often excluded from decision-making and implementation processes that prioritize top-down approaches driven by powerful actors such as funders, large intermediaries, international organizations, and central governments.12 However, given the value and importance of LLA for communities managing their adaptation to climate change, and for the practices, actions, and strategies they are adopting to enhance their climate change resilience, reduce community vulnerability, and promote sustainable development, it is crucial to incorporate local climate approaches into national decision-making and implementation processes of both climate and socioeconomic development goals. Hence, as Senegal develops initiatives to respond to the impacts of climate change, locally-led adaptation presents an untapped opportunity to ensure that they are effective, sustainable, and locally rooted. The following recommendations provide potential pathways to local policymakers and international actors for deepening adaptation and resilience through LLA.

For local policy makers and other actors:

- Decentralize and develop climate governance and institutions at the local level: Climate governance stakeholders must recognize the importance and added value of locally-led adaptation and encourage the integration of communities' endogenous adaptation practices into the various priority adaptation options of the NDC for greater efficiency, performance, and impact in climate action in Senegal.

- Encourage and support collaborations between research institutions, policy makers, civil society organizations, and local communities: This collaboration is critical to ensure that all relevant stakeholders are included in the identification, documentation, and communication of relevant local adaptation experiences to generate knowledge to inform and support decision-making and implementation processes of the NDCs and other national and local development policies and strategies.

- Invest to remove barriers related to technical capacity building and climate finance access for local communities: To successfully integrate locally-led adaptation into climate action planning in Senegal and improve synergy between adaptation options in the NDC and endogenous adaptation practices that are already well aligned, the government needs to invest heavily on building local human and technical capacity at all levels of society, actively seek innovative climate finance to support, and, where appropriate, scale LLA. This also requires the mobilization of domestic resources to sustain climate actions in the long term.

For the international community:

- Promote the integration of locally-led adaptation action into the implementation of national and global climate goals: Considering the alignment of community adaptation strategies and solutions with the priority adaptation options of the NDCs and other national policies as well as their added value in enhancing the health and well- being of local communities, the international community, through the UNFCCC, should recommend and encourage countries and their international partners to center LLA adaptation in their financial support and implementation processes.

- Adapt proactive and innovative ways to finance and ensure access to local-level actors: Climate facilities such as the GCF, the AF, the GEF, and bilateral development agencies must set up a common fund exclusively reserved for financing local adaptation initiatives directly led by communities to make endogenous practices more sustainable and increase the efficiency and performance of climate action.

5. Conclusion

After the validation of the NDC adaptation options in 2020, Senegal is moving to the implementation of NAPS addressing the issues of climate change impacts in several vulnerable sectors such as agriculture, coastal zones, and health. For the integrated and participatory implementation of climate actions and policies, the country has established a climate governance system involving relevant stakeholders, facilitating access to technical and financial capacities and integrating the needs of local communities.

The results of the case studies in the sectors of agriculture, coastal zone, and health in Daga Birame, Dionewar, and Widou Thiéngoly respectively show that solutions developed by communities are typically in line with adaptation options of the NDC priority sectors and other national climate change and sustainable development goals. However, they are generally not taken into account by the central government. Identified challenges include the federal government's lack of recognition and support, limited direct access to climate financing, and the lack of technical and organizational capacity. Furthermore, effective and sustained adaptation actions, as well as the overall implementation of climate and sustainable development goals in Senegal, are hampered by structural barriers such as institutional problems created by inadequate climate governance, which in turn limits the effective integration of communities’ adaptation practices into national policymaking and implementation processes, and contributes to the absence of local leadership in the planning and implementation of climate policies.

However, as the results of this project have shown, locally-led adaptation could provide an entry point for empowering local communities to take ownership of their adaptation strategies and become active participants in climate change actions. Relevant lessons learned and best practices from these three case studies demonstrate the real capacity of communities to identify and implement key adaptation strategies that can contribute to improving the effectiveness and efficiency of climate action in the country. That is, if limits in access to climate finance and technical capacities are well addressed.

In addition, LLA fosters community ownership and empowerment and ensures that the people most affected by climate change have a say in how their communities respond. LLA further recognizes that local communities have the best understanding of their environment and are well-positioned to identify and implement effective adaptation strategies. Locally led adaptation actions can, therefore, enhance the effectiveness of climate change actions at the local, national, and global levels by ensuring that adaptation strategies are targeted, needs-responsive, and efficient.

Endnotes

1 Climate Change Risk Profile: Senegal (2017, January). USAID. https://www.climatelinks.org/sites/default/files/asset/document/2017_USAID%20ATLAS_Climate%20Change%20Risk%20Profile%20-%20Senegal.pdf

McSweeney, C., New, M., Lizcano, G., & Lu, X. (2010). The UNDP Climate Change Country Profiles: Improving the Accessibility of Observed and Projected Climate Information for Studies of Climate Change in Developing Countries. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 91(2), 157–166. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26232858

2 Rapport de la Contribution Déterminée au niveau National (CDN). Ministère de l’Environnement et du Développement Durable (MEDD). Rapport final et Annexe, 68p. https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/NDC/2022-06/CDNSenegal%20approuv%C3%A9e-pdf-.pdf

3 Climate Change Risk Profile: Senegal (2017, January). USAID. https://www.climatelinks.org/sites/default/files/asset/document/2017_USAID%20ATLAS_Climate%20Change%20Risk%20Profile%20-%20Senegal.pdf

4 Programme Pays 2018-2030. Ministère de l’Environnement et du Développement Durable (MEDD) et Fonds Vert Climat (FVC). Rapport final, 124p. file:///C:/Users/Ibrahima%20SY/Downloads/PROGRAMME-PAYS-Senegal-3.pdf

5 Rapport de la Contribution Déterminée au niveau National (CDN). Ministère de l’Environnement et du Développement Durable (MEDD). Rapport final et Annexe, 68p. https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/NDC/2022-06/CDNSenegal%20approuv%C3%A9e-pdf-.pdf

6 Government of Senegal, 2015. Senegal Emerging Plan (PSE) for the period up to 2035. https://www.sentresor.org/app/uploads/pap2_pse.pdf

7 MEDD-MEPCI 2020. Analyse du processus de planification et de budgétisation au Sénégal pour une meilleure prise en compte de l’adaptation aux changements climatiques. Projet d’Appui Scientifique aux processus de Plans Nationaux d’Adaptation (PAS-PNA). Rapport provisoire, 30p. https://www.environnement.gouv.sn/sites/default/files/documentheque/deec%202.pdf

8 Government of Senegal, 2015. Emerging Senegal Plan (PSE) for the period up to 2035. https://www.sentresor.org/app/uploads/pap2_pse.pdf

9PNA-FEM, 2021. Analyse des lacunes en matière d’intégration du changement climatique dans les politiques sectorielles de développement au Sénégal : agriculture, inondations, infrastructure et santé. Rapport d’étude du Projet Plan National d’Adaptation (PNA) du Fonds pour l’Environnement Mondial (FEM), 130p.

10Vincennes M. E. Cartographie des instruments politiques d’adaptation de l’agriculture au changement climatique au Sénégal. Mémoire de Master 2 Sciences Po de Bordeaux., 2019. https://www.bameinfopol.info/IMG/pdf/memoire_master_2_gestion_des_risques_dans_les_pays_du_sud_marie_edith_vincennes.pdf

11 Westoby, R., McNamara, K. E., Kumar, R., & Nunn, P. D. (2019). From community-based to locally led adaptation: Evidence from Vanuatu. Ambio, 49(9),1466–1473. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13280-019-01294-8

12ACC. (2022). Adaptation Action Coalition: an overview. Foreign, Commonwealth, & Development Office, gov.uk. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/adaptation-action-coalition-an-overview

About the Author

Dr. Ibrahima Sy

Dr. Ibrahima Sy is a Senior Climate Change Fellow at APRI. He is currently a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Geography at the University Cheikh Anta Diop (UCAD), Dakar, Senegal. He is an Associate Researcher with the Centre for Ecological Monitoring (CSE) in Dakar. Dr. Sy previously worked at the University of Strasbourg as an Associate Professor and at the Swiss Centre for Scientific Research in Côte d’Ivoire as a Research Fellow.