This article is a part of a series of special thought pieces published by APRI in collaboration with the Deutsche Afrika Stiftung e.V.

Summary

- Although Africa (African Union, AU) and Europe (European Union, EU) have been interacting for centuries, a formal relationship between the two continents was only begun in the early 1970s with the signing of the Lome Convention.1

- The main focus of the AU-EU interactions has been trade and aid and, more recently, climate change and migration. This is evident from the fact that the EU has been and remains Africa’s largest trading partner.

- Little attention has been given to industrial policy and the industrialisation of the African continent in AU-EU relations. Critical issues such as skills development, technology transfer and building industrial capabilities have been sidelined.

- For the AU, industrial policy and industrialisation are central to the continent’s developmental aspirations. It is, therefore, surprising that industrialisation has not been highlighted in AU-EU relations.

- One reason industrialisation has not featured strongly in AU-EU relations is that, from the European perspective, an industrialised Africa does not serve the EU's interests; it would undermine the EU’s access to raw materials. This brings out asymmetries in AU-EU relations.

Introduction

Africa and Europe have been interacting for centuries. This relationship has evolved from mercantilist interests for the larger part of the history of the two continents, through the imperialistic domination of Africa, to the current phase of interaction which emphasises the need to deepen strategic partnerships and cooperation. In the last two decades, the European Union (EU) has made some efforts to transform this relationship from a donor-recipient type into one built on what the EU envisions to be an ‘equal’ partnership of mutual respect and benefit. For instance, a joint Africa Union (AU)-EU statement adopted at the 6th AU-EU Summit held in Dakar, Senegal, in 2022, stipulates that the renewed partnership between the EU and the African continent should be founded on ‘mutual respect and accountability, shared values, equality between partners and reciprocal commitments’ (AU-EU, 2022).

The current relationship between the two continents focuses on developing strategic partnerships around common challenges, including climate change, peace and security, migration, digital transformation, sustainable growth and job creation (EU, 2020). This paper focuses on the relationship between Africa and the EU on matters of industrial policy and Africa’s industrial development. Analysis of the AU-EU relationship reveals that from the beginning of the formal relationship between the two continents in the 1970s, little attention has been given to industrial policy and the industrialisation of the African continent. The main focus of the AU-EU interactions has been on matters of trade and aid and, more recently, climate change and migration. Critical issues such as skills development, technology transfer and building industrial capabilities have not featured strongly. This is despite the fact that the African continent, as a collective through the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) and now the AU, has consistently articulated a common vision which treats industrial policy and industrialisation as vital to its development aspirations. This paper provides reasons why key elements of industrial policy have largely been overlooked in the relationship between these two blocks.

AU-EU industrial policy cooperation

Africa and Europe have been interacting since before even the European voyages of discovery during the 15th century (Davidson, 1991 [1966]). While this context is important to bear in mind, this paper does not go into the history of this relationship; it focuses on the formal interactions between countries in the two continents, specifically on matters relating to industrial policy. One of the first formal initiatives to promote Africa-Europe relations was the Lome Convention, signed in 1975 between nine members of the European Economic Community (EEC, a precursor to the EU) and members of the Africa, Caribbean and Pacific (ACP) group of countries. The convention was seen as a means to promote cooperation between European countries and countries in the developing world.

In the Lome Convention, the cooperation between Africa and Europe focused on trade and aid relations. Trade relations were promoted by allowing EEC member countries free access to about 99% of exports from the ACP countries without trade reciprocal obligations (EC, 1977). In this arrangement, no attention was given to industrial policy or strategies to promote the industrialisation of the African continent; the focus was primarily on trade. With regard to aid, although different types of aid were provided to African and other ACP countries, this did not specifically target the growth of industrial activities in the recipient countries. As a result of low industrial development among African countries relative to EU countries, the dominant trade relationship between the two continents has been characterised by Africa and other ACP countries supplying primary commodities to EU countries, where they are processed into finished capital and consumer goods. It has been observed that the trade mechanism within the Lome Convention effectively established ‘a harmonious and stable relation between producers and users of raw materials’ (EC, 1977:1 emphasis added).

In 2000, the Cotonou Agreement replaced the Lome Convention as a new structure for promoting EU-ACP cooperation. For the EU, the Cotonou Agreement was seen as a mechanism for making ‘a significant contribution to the economic, social and cultural development of the ACP States’ by assisting them to navigate the challenge of globalisation (EC, 2000). While the Cotonou Agreement does specifically mention the need to promote the growth of a competitive industrial sector in Africa and other ACP countries, no strategic measures were outlined or implemented to that effect. The key objectives of the Cotonou Agreement include reducing and eventually eradicating poverty in ACP countries, and promoting the sustainable economic growth and gradual integration of ACP countries into the global economy (EC, 2000).

With regard to industrial policy, it is apparent that in both the Lome Convention and the Cotonou Agreement, the partners in the Africa-EU alliance have been operating on the belief that providing preferential access to the markets of EU member countries would in some way stimulate the growth of industrial production. This reasoning follows the mainstream economic theory which argues that openness to trade can induce industrial growth, diversification and economic development (see Chenery et al., 1986). This idea explains why industrial policy has not prominently featured in the Africa-EU cooperation. However, this view has been challenged by studies showing that attaining sustained economic growth in the current global economic context requires a special kind of industrial policy (Cherif & Hasanov, 2019; Chitonge, 2021). Some analysts have gone even further, arguing that sustained economic development is unlikely to be realised unless active industrial policy is implemented (Aiginger & Rodrik, 2020:1).

Evidence of the importance of industrial policy for the AU

Interestingly, African countries, individually as well as a collectively through the OAU and its successor, the AU, have consistently embraced the idea of formulating and implementing deliberate strategies to promote the growth and diversification of industrial activities on the continent (see AU, 2007; ECA, 2016). To illustrate that industrial policy has been a central feature of African countries’ development strategy, we need to look at the different initiatives outlined at the African continent level.

From the early days of independence in the 1960s, African leaders had regarded industrial policy as a strategic tool for the development of the continent, with the aim of improving the continent’s share in global industrial production and attain a reasonable degree of collective self-reliance. The first continental industrial development initiative was outlined in the Lagos Plan of Action (LPA; OAU, 1980) which declared 1980 as the first Industrial Development Decade for Africa (IDDA I), and the 1990s as the Second Industrial Development Decade for Africa (IDDA II). The LPA outlined several strategies aimed at achieving the objective of industrial growth on the continent such as designing and implementing industrial policy, training personnel to meet the required skills and establishing appropriate financial institutions (including the African Development Bank) to provide the necessary funding. The emphasis in the LPA was on promoting regional cooperation among African countries to overcome economic underdevelopment and dependence:

The industrialisation of Africa in general, and of each individual Member State in particular, constitutes a fundamental option in the total range of activities aimed at freeing Africa from underdevelopment and economic dependence. The integrated economic and social development of Africa demands the creation, in each Member State, of an industrial base designed to meet the interests of that country and strengthened by complementary activities at the sub-regional and regional levels (OAU, 1980: 15).

Interestingly, the LPA document highlighted the common tendency among developed countries, including countries in the EU, to discourage industrial development on the continent.

In 1996 the OAU launched the Alliance for Industrialisation of Africa (AIA) programme as part of the IDDA II (Chitonge 2019). This was followed in 2007 by the launch of the Accelerated Industrial Development for Africa (AIDA) programme. Unlike the earlier programmes, AIDA elaborated on several measures and policy directions to be implemented by AU member countries to fast-track industrial development on the continent. AIDA asserted that industrialisation is the engine of development and that underdevelopment on the continent can be explained in terms of low levels of industrialisation:

Industrialization is a critical engine of economic growth and development. Indeed, industrialization is the essence of development. That Africa remains the poorest region of the world, where 34 of the 50 least developed countries are located and in which poverty is on the increase, is a reflection of its low level of industrialization and marginalisation in global manufacturing (AU, 2007: 1).

In 2010, the AU launched the African Agribusiness and Agro-processing Development Initiative (3ADI) to encourage building productive capabilities on the continent. Many like-minded initiatives have since been launched at the continental level, including the Ten-Year Implementation Plan of Agenda 2063, adopted by the AU in 20132, as well as the Africa Industrial Week (launched in 2018) to raise awareness around the importance of industrial development on the continent.

From this brief review of industrial policy strategies adopted by the AU, it is evident that African countries have identified industrial policy as an important instrument for economic development (Chitonge, 2019). However, what is not clear is whether the AU member states have raised industrial policy as an important issue in their partnership with the EU. If the AU has raised the importance of industrial development in its engagement with the EU, it has not been given serious attention in their partnership. This can be attributed to the fact that the two blocks have different views on the role of industrial policy in economic development. In this particular partnership, the EU, the dominant partner, has cherry-picked strategic areas in which to cooperate with Africa. Promoting industrial development on the African continent is not one of them, for reasons discussed later in the paper.

The dominance of trade in the AU-EU partnership

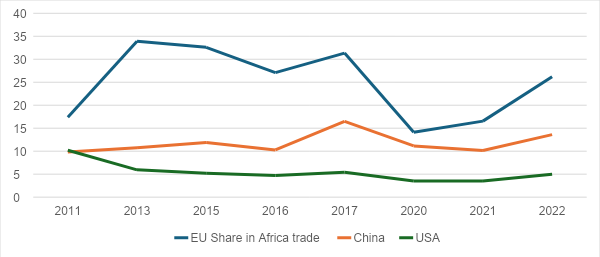

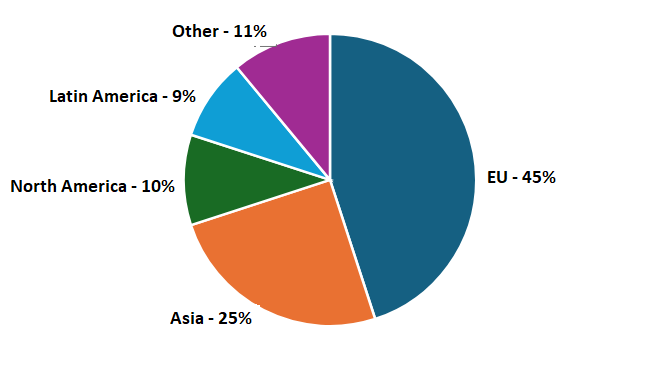

A close look at Africa-EU cooperation shows that industrial policy and issues related to industrial development have been largely sidelined. Since the mid-1970s, EU-Africa cooperation has predominantly revolved around trade and aid, not industrial development. Although the scope of issues covered in this cooperation has grown in recent years to include food security, peace and security, democratisation, migration, good governance, digital transformation, climate change, green transition, job creation, and investment promotion, trade and aid remain the core. The importance of trade in EU-Africa relations is evident in the fact that the EU has been Africa’s largest trading partner since the latter’s founding (Figure 1).

Source: Author, based on data from International African Trade Statistics (UNCTAD 2018) and IMF’s Direction of Trade Statistics (https://data.imf.org/regular.aspx?key=61013712 )

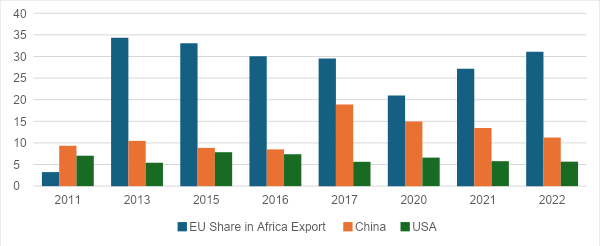

Although Africa’s share in the EU’s total trade has been small, averaging about only 4.7% over the last 15 years (IMF, DOTS website), the EU’s share in Africa’s total trade has accounted for an average of a quarter of Africa’s trade over the same period. We see similar proportions in Africa’s total imports and exports, with the EU emerging as the largest exporter and importer of African goods and services, despite China’s growing share (Figures 2 and 3)

Source: Author, based on data from International African Trade Statistics (2018) and IMF’s Direction of Trade Statistics (https://data.imf.org/regular.aspx?key=61013712 )

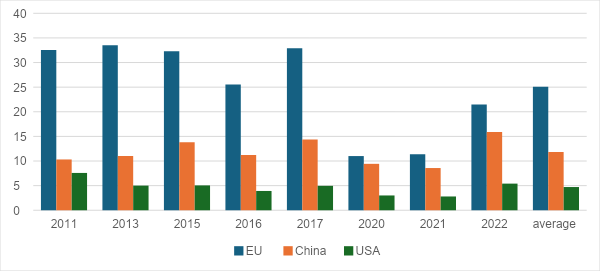

Analysis of the composition of the Africa-EU trade confirms that Africa’s export to the EU is predominantly primary goods, averaging 67% between 2011 and 2022, while the EU’s export to Africa is predominantly manufactured goods, averaging 70% over the same period (see IMF DOTS Website). In terms of the continent’s imports, the EU has been the largest source of imported goods and services, accounting for an average of close to 30%, which is almost double China’s share (Figure 3).

Source: Author, based on data from International African Trade Statistics (2018) and IMF’s Direction of Trade Statistics (https://data.imf.org/regular.aspx?key=61013712 )

In terms of foreign direct investments (FDI) into Africa, the EU is also the largest source of Africa’s FDI, accounting for an average of over 45% between 2016 and 2022, way ahead of China, the US and other regions (Figure 4).

Source: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD, 2023). World Investment Report 2023. New York: UNCTAD.

However, the larger share of this investment has gone into extractive and not manufacturing activities (Kapell, 2020; UNCTAD, 2023). Apart from policy statements, empirical evidence also suggests that Africa-EU relations have been characterised by asymmetries at different levels, with the EU extracting commodities from Africa.

Recent AU-EU partnership initiatives

Besides trading and investment, several other AU-EU cooperation initiatives have been initiated over the past two decades, starting with the drafting of the Joint AU-EU vision in 2007 in which the EU expressed a desire to partner with Africa more strategically beyond the conventional trade and aid arrangements. An example of this includes initiatives such as the Emergence Trust Fund for Africa, launched in 2015, the 5th Africa-EU Summit held in 2017 in Abidjan and the 6th Africa-EU summit held in Dakar in 2022, culminating in the Joint Vison for 2030 (EU, 2022).

There are several reasons which explain the EU’s growing interests in Africa. One is the growing influence of China, which is often seen as a threat to Western countries’ interests in Africa (Economist, 2019). This became clear at the 5th Africa-EU summit where a call was made to revive a ‘true alliance’ between Africa and Europe, with the then EU President Donald Tusk declaring that, ‘Today I call for a true alliance between our two continents to face our challenges and seize our opportunities together’ (emphasis added). The call to forge a ‘true alliance’ signifies the intention to transform the AU-EU partnership into something strategic for both continents. Although the EU president did not elaborate on what this new alliance would involve, at the same summit the AU Commission chair, Moussa Faki Mahamat, alluded to the need to transform the existing partnership into something more substantive, when he made a call ‘to build a strategic alliance, more than just a simple partnership dedicated solely to the quest for mercantile interests’ (Mahamat, 2017). Since the 5th AU-EU summit, several initiatives have been launched with the aim of giving the AU-EU partnership a facelift.

In terms of industrial development and industrial policy, the Africa-Europe Alliance for Sustainable Investment and Jobs (AEASIJ), launched in 2018, is probably the most relevant. It takes forward the proposal made at the 5th AU-EU summit to transform the partnership into a more substantive alliance. The AEASIJ communique argues that this alliance,

represents a radical shift in the way we work as partners towards a logic focused on Africa’s potential… The Alliance is about unlocking private investment and exploring the huge opportunities that can yield benefits for African and European economies alike (EU, 2018).

The AEASIJ initiative focuses on promoting investments mainly from Europe into the African continent and sees this as a strategy to bring the strengths of Africa and Europe to work together for the benefit of both continents. It is anticipated that 10 million jobs in Africa will be created in five years through the AEASIJ initiative.

Although the AEASIJ initiative does not specifically refer to any industrial activities or sectors, it states that in the drive to promote investment into Africa, priority will be given to ‘value adding sectors’ with the highest potential to create sustainable jobs for youth and women.

If it materialises, the private sector investment which this initiative is promoting has the potential to contribute to industrialisation and much-needed job creation, especially if the investments are directed into non-traditional sectors, particularly manufacturing industries. Unfortunately, both history and current FDI trends on the continent show that most of the investments have been directed into extractive activities which make little contribution to industrial development and job creation. According to the 2023 World Investment Report (WIR), although the EU is by far the largest source of FDI in Africa, with the UK leading at US D 60 billion, followed by France and the Netherlands at USD 54 billion, the bulk of these investments have been in energy and other extractive activities, with little going into the manufacturing sector (UNCTAD, 2023). If this trend continues, the envisioned job creation under AEASIJ will not come to fruition.

EU-Africa cooperation blueprint

The EU’s blueprint for cooperating with Africa is outlined in the Comprehensive Strategy with Africa (CSA), launched in 2020, which makes a strong case to ‘partner with Africa, our twin continent, to tackle together the challenges of the 21st century and to further our common interests and future’ (EU, 2020). CSA has identified a long list of common interests between Africa and the EU, including:

..developing a green growth model; improving the business environment and investment climate; boosting education, research and innovation, the creation of decent jobs and value addition through sustainable investments; maximising the benefits of regional economic integration and trade; ensuring food security and rural development; combatting climate change; ensuring access to sustainable energy and protecting biodiversity and natural resources; promoting peace and security; ensuring well-governed migration and mobility; engaging together on the global scene to strengthen the multilateral rules-based order, promoting universal values, human rights, democracy, rule of law and gender equality (EU, 2020: 1).

From this list, it is evident that the partnership is envisioned to go beyond traditional Africa-EU cooperation around trade and aid. Although not specifically stated, there are a few areas that relate to industrial development, such as value addition, investment and job creation. It is, however, interesting to note that the push for cooperation is strongly driven from the EU side, leaving the impression that the AU is largely a passive partner. Although the AU has not explicitly objected to any of these initiatives, there is little indication that the partnership is forged on an equal basis, with each partner putting their priorities on the table to shape the cooperation (Kappel, 2020). If the AU-EU partnership were on an equal footing, we would expect the AU to push the agenda of industrialisation as a key issue, given the central role of industrialisation in the AU’s development agenda. As noted above, industrialisation in the AU-EU partnership is only implicitly alluded to, though the AU takes this as a critical aspect of the continent’s development strategy. On the other hand, the EU’s obvious interests feature strongly in the different AU-EU partnership initiatives, with migration top of the list.

Reasons for the low priority given to industrial policy in the Africa-EU partnership

There are several factors that explain the lack of attention given to industrialisation in the Africa-EU partnership. Among them, three stand out. First, EU member countries do not believe in industrial policy which requires the state to play a central role in the economy; they rather see the market as the most efficient institution for achieving industrialisation. As such, they do not see the need for industrial policy which would then assign a stronger role to the state. Second, an industrialised Africa does not serve the interest of the EU, since this would undermine the EU’s access to raw materials. As the trade data presented above show, the EU benefits from maintaining Africa as a source of raw materials and a market for capital and consumer goods. Third, since most of the initiatives are initiated by the EU – the dominant partner in the relationship – it is primarily the issues of strategic interest to the EU which receive attention.

To create a genuine partnership, the AU and EU must address the existing asymmetries, including levels of industrialisation. We therefore make the following recommendations.

Recommendations

- To create a sustainable and healthy AU-EU strategic alliance, the two blocks must confront and address the existing asymmetries in this relationship. This will help promote mutual respect and identify common strategic interests.

- Since industrialisation is central to the AU’s vision for the African continent, industrial policy must be a strategic area of cooperation between the AU and the EU.

- To forge ‘a true alliance’ between the two continents, a compromise on the strategic AU-EU issues is crucial. As things stand, the EU, as the stronger partner, has pushed its strategic interests on the alliance’s agenda while the AU’s central interests have been sidelined.

Conclusion

The relationship between Africa and Europe has evolved over centuries. Initiatives to formalise this relationship started in the 1970s with the signing of the Lome Agreement, which the Cotonou Agreement later replaced at the beginning of the new millennium. While cooperation between the two blocks of countries has historically focused on trade and aid, the scope of issues on which they seek to cooperate has grown to include a wide range of issues such as migration, peace and security, climate change, investment, food security and sustainable development. However, though the AU has clearly stated that industrial policy and industrialisation are critical components of the continent’s development strategy, the issue has taken a backstage in the AU-EU alliance.

Endnotes

- The AU-EU or EU-AU shorthand is used to refer to the period after the AU came into existence while the Africa-EU or EU-Africa shorthand is used to cover the period before the AU was created.

- The first Ten-year Implementation Plan covered the period 2013-2023, the Second Ten- Year Implementation Plan will run from 2024-2033.

References

African Union Commission & Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. (2022). Africa’s development dynamics 2022: Regional value chains for sustainable recovery. Addis Ababa: AU/OECD.

Aiginger, K., & Rodrik, D. (2020). Rebirth of industrial policy and an agenda for the twenty-first century. Journal of Industry, Competition and Trade, 20(4), 189-2007. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10842-020-00352-3

Chenery, H., Robinson, S., & Syrquim, M. (1986). Industrialisation and growth: A comparative study. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Cherif, R., & Hasanov, F. (2019). The return of the policy that shall not be named: Principles of industrial policy (IMF Working Paper No. WP/19/74). International Monetary Fund.

Chitonge, H. (2019). Industrialising Africa: Unlocking the economic potential of the continent. New York/Berlin: Peter Lang.

Chitonge, H. (2021). Industrial policy and the transformation of the colonial economy in Africa: The Zambian experience. London: Routledge.

Davidson, B. (1991). Africa in history: Themes and outlines (Reprint, originally published 1966). London: Phoenix Press.

European Community. (1977). The Lome Convention: A North/South initiative. European Community Information Services.

European Community. (2000). Partnership agreement between the members of the African, Caribbean and Pacific Group of States and the European Community and its member states. Signed in Cotonou on 23 June 2000. Protocols - Final Act – Declarations No. 2000/483/EC.

European Union. (2018). Communication on a new Africa-Europe alliance for sustainable investment and jobs: Taking our partnership for investment and jobs to the next level (Com(2018)643 Final). Brussels.

European Union. (2020). Towards a comprehensive strategy with Africa: A joint communication to the European Parliament and the Council. Brussels.

European Union-African Union. (2022). 6th European Union-African Union summit: A joint vision for 2030.

International Monetary Fund. (n.d.). Direction of Trade Statistics (DOTS) database. https://data.imf.org/regular.aspx?key=61013712

Kappel, R. (2020). Africa-Europe economic cooperation: Using opportunity for re-orientation. Fredrich Ebert Stiftung.

Lopes, C. (2022, June 16). Decolonising Africa-Europe relations [Lecture]. University of Oxford Martin School. https://www.oxfordmartin.ox.ac.uk/events/decolonising-africa-europe-relations

Mahamat, F. M. (2017, November 29-30). Opening remarks by the African Union Commission Chair, Mr. Moussa Faki Mahamat at the 5th AU-EU Summit. Abidjan.

Organisation of African Unity. (1980). Lagos Plan of Action. Addis Ababa: OAU.

The Economist. (2019, March 7). The new scramble for Africa: This time winners could be Africans. https://www.economist.com/leaders/2019/03/07/the-new-scramble-for-africa

Tusk, D. (2017, November 29-30). Introductory remarks by EU President Donald Tusk at the 5th AU-EU Summit. Abidjan.

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. (2023). World investment report 2023. UNCTAD.

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. (2018). International African Trade Statistics Yearbook 2018. UNCTAD.

United Nations Economic Commission for Africa. (2016). Transformative industrial policy for Africa: Innovative institutions, effective processes and flexible mechanisms. UNECA.

About the Author

Horman Chitonge

Horman Chitonge is a professor at the Centre for African Studies and a research associate at PRISM, School of Economics (UCT University of Cape Town (UCT). He is a visiting research fellow in the Global Justice Programme at Yale University and a visiting professor at the African Studies Centre at Tokyo University of Foreign Studies. His research interests include industrial policy, agrarian political economy and alternative strategies for economic growth in Africa.