This article is part of a series on “What is Germany’s Africa Policy?” The series is edited by Dr. Melanie Müller and Dr. Olumide Abimbola.

Summary

- German-African energy relations have been focusing far too long on development cooperation and, thus, mainly covering aspects such as energy poverty or decentralised access to renewables.

- Under the new ‘traffic-light coalition’, the author argues that we can identify a more comprehensive cooperation style, combining energy diplomacy and energy foreign policy, development cooperation, and not least technology-driven cooperation.

- In recent years, funding has expanded to strategic initiatives that are transregional or even transurban and involve multi-stakeholder partnerships, such as the Just Energy Transition Partnership or the Loss and Damage Fund.

- German-African energy diplomacy addresses two competing interests: First, an interest in fostering renewable energy cooperation, visible in industrial cooperation for solar and wind parks, green fund opportunities and, most recently, hydrogen partnerships. Second, an interest in diversifying fossil fuel relations and tapping Africa’s oil and gas markets to import liquified natural gas and erect new terminals.

- To balance German and African diplomatic interests, a search for common normative orientations and a break from the traditional import/export dichotomies are crucial.

Introduction

German-African energy relations are undergoing major transformations. For decades, the relationship mirrored typical dichotomies along themes such as energy extractivism, “under” development, and deficiency. This meant that pressing problems such as “energy poverty” were not considered as a question of justice but rather accepted as an a-political fact. Today’s energy relations paint a more ambivalent picture that provides more room for manoeuvre: They feature African green entrepreneurship and frame energy as a foreign policy issue with African states advancing in energy diplomacy, indicating that German-African energy relations have diversified. The current constellation pays tribute to Germany’s diplomatic strategies and economic interests and expresses a commitment to contribute to meaningful action at the “energy/development nexus”, yet also reflects a desire to dominate green geopolitics on African terrains. In this light, Germany’s new Strategy for Africa emphasises the commitment towards a just transition, aiming at green finance flows, energy partnerships, and urban sustainability. After a brief historical recapture, the following piece takes account of recent developments by looking at current trends and concludes with a set of policy recommendations for cooperation based on energy justice.

Recapture: German-African energy relations

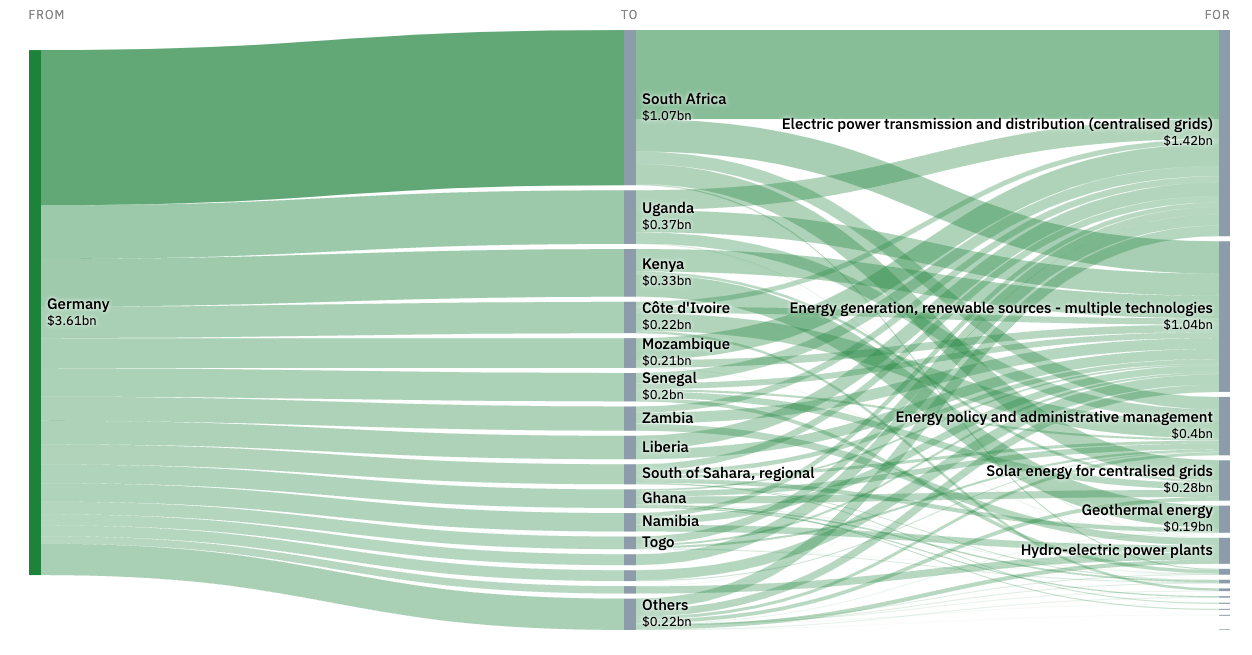

For the most part, German-African energy relations have been subsumed under the umbrella of development cooperation, thus mainly covering aspects such as energy poverty or decentralised access to renewables. From 2002 to 2020, Germany committed a total US$ 3.61 billion in development finance to Sub-Saharan Africa for energy, with annual sums ranging between US$ 245 million and US$ 600 million during the last decade. This sum is about as high as the amount provided by the United States from 2002 to 2022 (US$ 3.58 billion). The top five African recipients of German aid were South Africa, Uganda, Kenya, Côte d’Ivoire, and Mozambique. Cooperation concentrated mostly on electric power transmission and grid infrastructure (US$ 1.4 billion), as well as on renewable energy generation (US$ 1.0 billion), but a considerable amount (US$ 401 million) was also spent on energy policy consultation and management initiatives.

Fig. 1: All recipients of development finance from Germany in Africa (all Sub-Saharan Africa) for Energy

Development finance from Germany to Africa (all Sub-Saharan Africa) for Energy was committed to 16 different countries. The largest amounts were $1.07 billion to South Africa, $369 million to Uganda and $328 million to Kenya.

Source: AidAtlas 2022

In the early 2000s, the boom of Germany’s solar and wind industry meant that the expansion to promising markets with attractive geophysical potential gained importance, fuelled also by the impulse to liberalise trade relations via the Cotonou Agreement and the push for Economic Partnership Agreements. This expansion also gave rise to the Trans-Mediterranean Renewable Energy Cooperation, later labelled as Desertec, the administrative backbone of which was, by and large, located in Germany. While today the questionable aspects of the project (territorial claims and land-use conflicts, energy extractivism, lack of local integration) are clear, in those days the project was featured as a win-win solution, providing renewable energy to European countries via high-voltage direct current transmission and creating stable jobs in the Maghreb. Besides Desertec, numerous public-private partnerships, often under the auspices of the GIZ (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit – German society for international cooperation), reached out to Egypt, Namibia, and South Africa to distribute mini-grid systems or solar home systems as part of rural development programmes.

However, a growing concern for geopolitics meant that, besides the development focus, strategic interests have also gained importance. Even in the 2000s, an interest in diversifying energy markets and in decreasing dependency on Russian gas resulted in African gas resources gaining attraction. Yet, this attention occurred at a time when Russia and China likewise intensified their engagements by tapping oil and gas resources in Angola, Sudan, Mozambique, and Nigeria. Under the auspices of the German government, the “Marshall Plan with Africa” promoted closer cooperation on fossil and clean energy, thus intertwining developmental norms and geopolitical dominance. The new instrument of “reform partnerships” aimed at privileged cooperation with those countries that expressed commitment to private sector reform. Germany entered agreements with Tunisia, Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire, Ethiopia, Morocco, and Senegal. As an example, besides the well-known goals of mobilising private capital, fostering job creation, and engaging in good governance, the partnership with Ghana concentrates on renewable energy and energy efficiency: power sector reform integrating independent power producers, risk mitigation for energy investment, a solar tender with competitive bidding, and vocational training for technicians and engineers. In this light, Germany also played a significant role in deepening the EU’s strategic partnership with South Africa, with a focus on renewable energy cooperation, but also including carbon capture and fracking technologies.

Still, what many of the earlier initiatives had in common was a neglect of local energy infrastructures, namely with regard to the political dimension of energy transitions. Although several African countries laid the foundations for their renewable energy policies in the 2000s, the Desertec initiative, for instance, was not tied to the domestic energy policies of the Maghreb countries but promoted ‘energy enclaves’, which is why the early concerns with accusations of ‘energy colonialism’ seem telling with today’s hindsight. Indeed, soon after Desertec’s launch in the 2000s, civil society activists expressed this criticism, and the later decline of the initiative now stands as a warning against such territorial claims.

Under the new ‘traffic-light coalition’, we can identify a more comprehensive cooperation style, combining energy diplomacy and energy foreign policy, development cooperation and, not least, technology-driven cooperation. This three-fold framework holds some tensions, as these perspectives do not always align. Still, the common narratives of energy justice and a just transition bear potential for closer African-German cooperation. Yet they require a norms-driven energy foreign policy, the development of corresponding Pan-African/German narratives and, not least, an alignment with national transition plans.

Reflection: Three trends in German-African energy relations

German-African energy relations reflect a set of partially contradictory motives for cooperation: development, diplomacy and, not least, technology. First of all, there is the energy development nexus, aiming at combating energy poverty but also fostering market-based solutions for increasing fair and reliable access to renewables. Second, there is the sphere of energy diplomacy, representing both Germany’s strategic interests in energy resources and the intention to cooperate on a mutual basis. Finally, for a long time, technological cooperation was subsumed under either of the first two motives. Yet, since Germany launched its hydrogen strategy, a new export/import relation has been materialising and has given this motive new meaning. Technological cooperation would involve exporting hydrogen technologies to emerging economies while importing large quantities of green hydrogen from the Global South to decarbonise steelworks and automotive industries.

1. Development Cooperation: Combatting energy poverty or featuring financialisation?

Cooperation at the energy/development nexus has been one of Germany’s strengths within EU-Africa energy cooperation. Supporting energy access, promoting smart grids and solar home systems as part of rural development, realising infrastructure projects, and providing policy advice are all important parts of the GIZ’s and the KfW’s (Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau – German government-owned development bank) portfolios. In recent years, funding has expanded to strategic initiatives that are transregional, or even transurban, and involve multi-stakeholder partnerships such as Energising Development (EnDev) or the Global Energy Transformation Programme (GET.pro).

At COP 26, Germany was one of the architects launching the Just Energy Transition Partnership, which intends to support just transition processes in countries that face huge fossil-fuel path dependencies combined with limited policy space to decarbonise on their own. Such countries – Nigeria, Angola, Mozambique, to name but a few – face a huge transition risk, which eventually may result in a loss of revenues (“petrodollars”), political instability and social decline (see p. 120). South Africa was the first partner country, with US$ 8.5 billion commissioned to decarbonise its energy system, to create green jobs, and to orchestrate a smooth transfer towards a green economy. Senegal, India, Vietnam, and Indonesia will be the next partner states. This commitment again expresses Germany’s strategic interests in engaging in multi-stakeholder initiatives that operate on a larger scale. Still, as such initiatives involve both public and private actors, they also represent a trend towards a financialisation of development, marking a gradual shift from previous energy initiatives, which focused on combating energy poverty as part of rural development towards market-orientation.

Financialisation in this context means that renewable energy projects first of all need to guarantee a return on investment and need to be a bankable case, rather than focusing primarily on development-related goals such as combating energy poverty or fostering job creation in the energy sector. This requirement limits the range of energy transition projects to those that are able to meet investors’ interests, whereas projects in conflict-prone regions are considered too ‘risky’. Yet, to ensure that the coal-to-clean transition caters for social needs, norms such as energy justice or hydrogen justice need to underpin the cooperation. Small-scale projects, such as the BMZ’s (Bundesministerium für Wirtschaftliche Zusammenarbeit und Entwicklung – German Federal Ministry for Cooperation and Development) initiative “Green People’s Energy for Africa'' (“Bürgerenergie für Afrika”), reflect precisely these normative orientations by pointing to the potentials of energy democracy, African public ownership, and public participation. Decentral and small-scale renewable energy projects provide the opportunity to empower civil society as they facilitate knowledge and skill transfer, meet people’s energy needs, and can be aligned more easily with domestic energy transition initiatives.

2. Energy diplomacy, geopolitics, and energy foreign policy: Renewables meet fossilism

Energy diplomacy is underpinned by a normative triangle: security of supply, competitiveness, and sustainability. The Ukraine war and the termination of Germany’s diplomatic relations with Russia have compromised energy security and have resulted in energy scarcity due to a long-standing dependency on Russian gas, which in the past 15 years had even been strengthened ‘thanks’ to infrastructural lock-ins. In attempts to navigate this “security-sustainability nexus”, it did not come as a surprise that German energy diplomacy aimed to advance energy cooperation with African countries and the MENA (Middle East and North Africa) region. German-African energy diplomacy thus addresses two competing interests: a green objective and a fossilist objective.

A ‘green objective’: Advancing as a key player on renewable energy emerging markets, for example, those in Kenya, Egypt, South Africa, or Namibia, that offer both favourable geophysical conditions and attractive policy frameworks such as market-based policies (green funds, energy auctions, etc.). This advance is reflected in industrial cooperation for solar and wind parks, for instance shares in South Africa’s procured energy projects, in green fund opportunities, and in risk guarantees for green investment. From a foreign policy standpoint, this cooperation mirrors the desire for competition and the urge to regulate both via strategic partnerships and fintech means. Hydrogen diplomacy is the most recent example of this orientation, as a one-of-its-kind approach to curate hydrogen relations. Nuclear energy cooperation is no longer favoured due to Germany’s nuclear exit, and earlier attempts to export nuclear technology have ceased.

That objective is contrasted by a ‘fossilist objective’, that is, to tap alternative oil and gas markets. German energy diplomacy has expressed the motivation to cooperate with Senegal to import liquified natural gas and erect new terminals. This move was instantly supported by the Senegalese president Macky Sall but will create long-lasting path dependencies for Senegal that prolong postcolonial extractivist patterns, which is why Senegalese environmental activists have stood up against such plans.

3. Hydrogen roll-out: Mutual cooperation or African techno-fixes for German problems?

Certainly the most exciting development is the current roll-out of hydrogen diplomacy with African countries, which highlights both Germany’s urge to decarbonise steelworks and heavy industry, thanks to large-scale hydrogen imports, and its interest in excelling as a technological leader in hydrogen technologies. Under the former Science Minister, Karliczek, more than 25 countries were approached. Yet the rationale for this move seemed inconsistent in some cases, given that energy cooperation with landlocked and drought-stricken countries such as Niger or Burkina Faso would require huge infrastructural commitments and would come with increased risks for water security. In several cases, geophysical potentials such as high solar radiation or access to freshwater resources are accompanied by equally high social and ecological risks, such as unfair labour conditions, water scarcity or a history of land-grabbing. And even in cases with more favourable conditions, such as in Namibia, the sheer land and water requirements for hydrogen production mean that hydrogen projects come with huge social and ecological risks. Land risks refer to the risk of energy-induced displacement and land use change; water risks may play out in water scarcity or in risks for marine ecosystems due to large-scale desalination.

Such constellations can succumb to an old-and-new sense of technocratic entitlement, portraying Southern terrains as "empty" and ready to cater to the needs of Northern nations, be it resource demands or green economy requirements. African hydrogen strategies navigate these tensions, with South Africa being outspoken on using hydrogen for its own decarbonisation attempts, Morocco combining local use and export, and Namibia aiming at exporting hydrogen, synthesised fuels and fertiliser on global and regional scales. German-African hydrogen governance needs to consider these different orientations and needs to align the individual interests.

Meanwhile, a more nuanced picture is forming along the lines of scientific cooperation and hydrogen diplomacy. For scientific cooperation, the WASCAL and SASCAL initiatives (West African Science Service Centre on Climate Change and Adapted Land Use; South African Science Service Centre for Climate Change and Adaptive Land Management) are engaging in prototype projects and arranging student training and exchanges with German universities. At the same time, hydrogen diplomacy is creating a background structure to establish an arena for negotiations on hydrogen projects in Nigeria, Angola, Saudi Arabia, Kazakhstan, and Ukraine. Some Memoranda of Understanding, such as the one agreed between Namibia and Germany, reflect a common interest in respecting general human rights and environmental and social standards, whereas other Memoranda of Understanding, such as the ones with the Emirates or Saudi Arabia, do not even mention these aspects.

A new narrative that would facilitate addressing socio-ecological concerns, needs, and common interests in a more structured way is the “hydrogen value chain”, that is, a turn towards understanding hydrogen production not as an import/export trade but rather as a production chain along which value is created and standards are certified. This narrative would also show that African states such as South Africa, Namibia, or potentially also Nigeria are expressing a strong interest in using green hydrogen not as a new resource to be exported but more as a Pan-African good that has its value in greening own steel works, ammonia production, or automotive industries.

Recommendations

To advance German-African energy cooperation, the following recommendations may contribute to a deeper and more equal exchange.

To balance German and African diplomatic interests, a search for common normative orientations and a break from the traditional import/export dichotomies are crucial. Energy transition and decarbonisation need to rely on a common understanding. A much-sought normative basis could be provided by mainstreaming energy justice as a standard clause in Memoranda of Understanding, as a requirement along energy value chains or within Just Transition Partnerships. This mainstreaming would involve distributive (access to energy), procedural (who participates), and recognitional (whose rights are met) justice but would also point to restorative (which historical injustices exist) and epistemic (who owns energy knowledge) justice. In this regard, the new concept of “hydrogen justice” outlines how these goals can be achieved for the emerging hydrogen cooperation. It would also create more awareness for neocolonial notions, such as territorial entitlements, that still underpin part of the energy relations.

Furthermore, energy cooperation needs to ensure that competition for energy markets does not create a “race to the bottom”, which is currently visible, for instance, in the Angolan-Namibian competition for cheap hydrogen production, probably at the expense of social and environmental standards. The “energy value chain” may serve as a powerful concept for African-German energy cooperation that transcends the old import/export geographies. In this regard, regional integration and the application of the Supply Chain Act (Lieferkettengesetz) would guarantee stronger Pan-African benefits. These benefits should materialise in a certificate for fair green hydrogen and in common standards for the whole hydrogen value chain.

About the Author

Franziska Müller is Assistant Professor for Global Climate Governance at the University of Hamburg. Her research interests include global climate and energy governance, political economy of energy, political ecology and postcolonial and poststructuralist approaches to International Relations theories. Franziska volunteers as a liaison officer for the Heinrich-Böll Foundation. She has studied political science, cultural anthropology, and economics in Tübingen, Frankfurt, and Birmingham and held teaching positions in Pretoria, Kassel, and Cape Coast.