Summary

- Major progress has been made in the AfCFTA Secretariat’s trade facilitation mandate; key projects and tools supporting adjustment costs, trade monitoring, cross-border payments and other topics have been launched.

- Progress is also being made at the continental level in negotiating the accompanying AfCFTA protocols. Under Trade in Goods, the Rules of Origin negotiations are currently at 88.3%, and they are expected be completed soon, allowing full implementation.

- To benefit from the AfCFTA, countries are working on regional and national levels to share information on the AfCFTA with their private sectors but also to ensure the readiness of soft and hard trade infrastructure.

- The launch of the Guided Trade Initiative has helped test the AfCFTA provisions and instruments but should not downplay the need to start implementing the full AfCFTA.

- Major challenges include clashes between national and continental aspirations that are already evident in the slow negotiations and that will need to be mitigated when the agreement is implemented.

- The Secretariat is playing a strong trade facilitation role while encouraging national ownership. It needs additional support to expand its capacity and reach.

Executive Summary

The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) agreement is one of the biggest continent-wide projects aimed at economic integration and African industrialisation through increased intra-African trade. The agreement’s Secretariat has launched an interim trading arrangement to test the agreement’s provisions while negotiations are ongoing. National, regional and continental institutions are also preparing for the AfCFTA by putting the necessary infrastructure and processes in place. Progress has been made on all fronts, and the agreement continues to enjoy significant political will. This paper presents an assessment of trade readiness on three levels:

- Continental: Negotiations under the different protocols are at various stages of completion, albeit behind schedule. The Guided Trade Initiative is a key development on the continental level and injects some energy into the implementation process. The Secretariat has advanced significantly in its trade facilitation mandate. It has set up various tools, mechanisms and resources to support the implementation process. Collaboration is increasing between the Secretariat and other continental entities such as the African Development Bank and the African Export Import Bank.

- Regional: As “building blocks” of the AfCFTA, the regional economic communities (RECs) recognised by the African Union have been playing a part in AfCFTA negotiations by supporting and coordinating the tariff offers submitted by member countries. They help fill capacity gaps for state parties with lower expertise and are also participating in harmonizing preferential trade provisions across the RECs under the AfCFTA. They will also support the identification and settling of disputes.

- National: Implementation plans have either been finalised or are almost finished. Most state parties are actively preparing their private sector to leverage the AfCFTA for larger markets. Designated Competent Authorities have largely been appointed, and structural reorganisations are happening within governments in response to the AfCFTA.

There are, however, some challenges:

- A significant part of the financial and technical support for the AfCFTA is from external partners. This source of support may present issues related to sustainability and diverse interests.

- Clashes between continental aspirations and national priorities may already be affecting the implementation of the AfCFTA, as evidenced by the delayed completion of the Rules of Origin negotiations.

- The growing complexity of the agreement will be confronted by the varying capacity levels of national institutions with the mandate to implement it.

- There are still significant gaps in trade facilitation measures such as transport infrastructure and logistics. Mobilising political and economic resources for trade facilitation on the continental, national and regional levels may also prove challenging.

- The global environment and geopolitics, such as external efforts towards establishing bilateral trade agreements with state parties, continue to intersect with the AfCFTA. The volatile investment environment is also a challenge, given the immense capital needed to scale production in response to the AfCFTA.

Innovative ideas are paramount to finding common ground among the various interests represented in the free trade area and sustainable solutions to identified challenges. Getting the AfCFTA off the ground and ensuring the success of its eventual implementation will require lessons to be learned from Africa’s RECs, which also serve as building blocks for the AfCFTA. The following recommendations are put forward:

- Larger state parties better positioned to benefit from the AfCFTA need to take a more cooperative approach to implementation and consider making greater concessions for collective benefit. The AfCFTA also calls for increased coordination of production policies and investment promotion.

- The sustainability of AfCFTA support can be addressed by institutionalising the local and foreign structures through which the support is delivered. Sustainable trade finance should be a top priority for all actors.

- Better control of the messaging and narratives around the AfCFTA can help prime African governments and the public for implementation challenges while strengthening their support for the agreement.

- All decisions taken at critical junctures should be weighed against the broader objectives of the AfCFTA with a long-term outlook. It is important that short-term benefits are not put ahead of overall goals.

- The participation of private sectors in negotiations and implementation needs to be increased, also in recognition of the role they can play in trade facilitation.

1. Introduction

The initiative to create a single African market has existed in the pan-African political discourse for decades. The continent was set on the path to actualising the goal after the creation of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) agreement was included in the African Union’s (AU) 2063 agenda. The agreement was signed on 21 March 2018, came into force on 30 May 2019 and became operational on 7 July 2019. After delays caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, the free trade area (FTA) was launched on 1 January 2021. The agreement aims to boost intra-African trade by eliminating 97% of tariff lines on goods and services as a pathway to industrialisation and prosperity on the continent. It will be gradually implemented and at different paces for three categories of countries Least Developed Countries (LDCs),1 non-LDCs and the G6.2

LDCs have ten years to reach 90% liberalisation and non-LDCs have five years. Similarly, LDCs have 13 years to reach 97% liberalisation and non-LDCs have 10 years.3 The G6 countries have negotiated a 15-year period for the gradual liberalisation of 97% of tariff lines. The rationale behind these distinctions is the cushioning of tariff revenue lost in less developed countries.

World Bank’s Projections of AfCFTA Benefits

- Lift 30 million Africans out of extreme poverty and boost the incomes of nearly 68 million others who live on less than $5.50 a day.

- Boost Africa’s income by $450 billion by 2035 (a gain of 7 percent) while adding $76 billion to the income of the rest of the world.

- Increase Africa’s exports by $560 billion, mostly in manufacturing.

- Spur larger wage gains for women (10.5 percent) than for men (9.9 percent).

- Boost wages for both skilled and unskilled workers—10.3 percent for unskilled workers, and 9.8 percent for skilled workers.

Source: World Bank

Through mechanisms that have been set up to monitor non-tariff barriers (NTBs) and resolve disputes, the AfCFTA will also address NTBs that hinder cross-border trade in Africa, such as transport costs, inefficient border processes and excesses by border officials (including extortion and harassment). It seeks to correct colonial trade flows by incentivising value-addition, the production and exchange of higher value goods on the African continent as opposed to primarily raw materials and commodities. The agreement is based on the recognition that intra-African trade flows have a higher percentage of value-added manufactured goods, providing a basis for trade-driven industrialisation. It has eight protocols covering trade in goods and services, dispute settlement, investment, intellectual property rights, competition policy, digital trade and women and youth in trade, as shown in Table 1.

Although trading under the AfCFTA was announced as having commenced in January 2021, commercially significant trade is yet to occur under the agreement. This lack of trade is primarily due to the delayed Phase 1 negotiations on trade in goods and services, particularly the negotiations on Rules of Origin (RoO). To maintain the momentum around the agreement, the AfCFTA Secretariat (governing body) launched a Guided (and facilitated) Trade Initiative (GTI) in October 2022. Among the 29 countries that have submitted their tariff offers, eight countries (Cameroon, Egypt, Ghana, Kenya, Mauritius, Rwanda, Tanzania and Tunisia) met the requirements for participation in the GTI and were selected to launch the initiative. The first shipment under this initiative - Exide batteries from Kenya to Ghana - was delivered on September 23, 2022, prior to the launch, and a few more have since followed. The GTI is intended as a form of pilot phase of the AfCFTA, which will help test the agreement’s regulatory instruments, among other aims.

This paper discusses the question of member countries’ trade-readiness for the AfCFTA with a focus on the countries included in the GTI. An additional country, Nigeria, was included in the analysis due to its size and importance to the success of the agreement. The analysis teases out some key challenges and their implications and proffers recommendations that will help increase the likelihood of the AfCFTA’s success.

2. AfCFTA Implementation Status

The implementation status of the AfCFTA can be examined through three lenses: continental, regional and national.

2.1 Continental

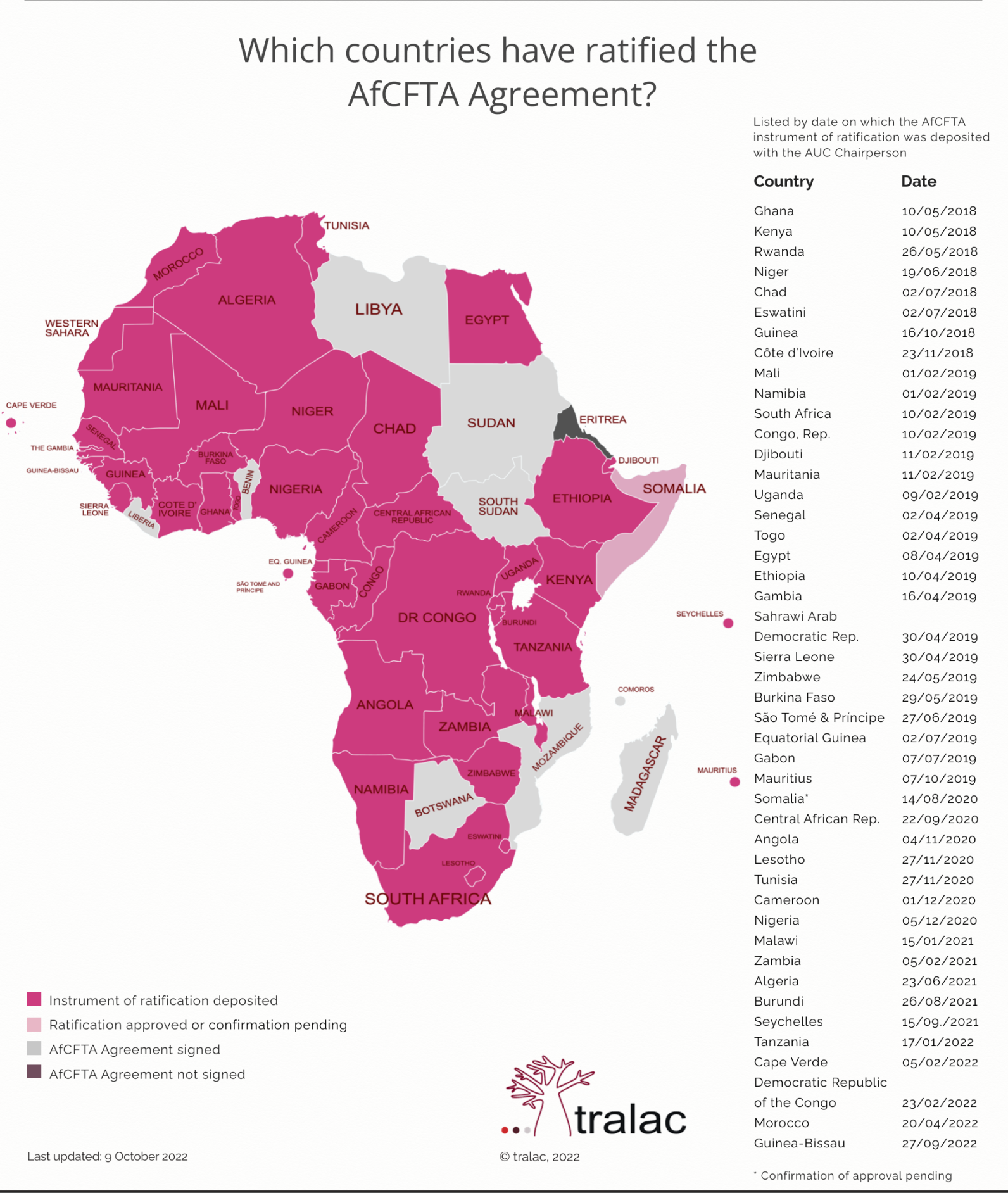

As of September 22, 2022, 54 countries4 had signed the AfCFTA agreement and 43 countries had deposited their instruments of ratification, as Figure 1 shows. This majority more than meets the minimum requirements for bringing the AfCFTA into force. However, before trade can fully commence, tariff offers must be submitted by member countries. The AfCFTA intends for 90% and 97% of tariff lines to be eventually liberalised in the first and second phases, respectively. However, it does not stipulate which tariff lines countries are mandated to liberalise. Therefore, tariff offers need to be submitted by countries, regional economic communities (RECs) and customs unions; they will form the basis of preferential trade under the agreement. The AfCFTA Secretariat has received 29 tariff offers for trade in goods that could be considered complete but is still waiting on several others. The tariff offers are largely dependent on the RoO negotiations, which are experiencing some delays.

Figure 1: AfCFTA Ratification Status

Note: Reprinted from Trade Law Centre, 2022

The RoO concern the criteria used to assess the nationalities of products to determine their qualification for trade within certain agreements. In the context of the AfCFTA, the RoO will be used to certify products as “African-made” and qualify them for free trade. There are two broad categories of RoO: rules that apply to all products, or Regime Wide Rules (RWR), and rules that apply to specific products, or Product Specific Rules (PSR). A set of common RWRs have been agreed on, but the PSRs have not been finalised. The RoO negotiations are affecting the tariff offers because they can affect the decision of an AfCFTA member country to liberalise tariffs on a particular product, or to list it as a sensitive product. Stricter RoO require almost all the raw materials and transformation of a product to be from within the preferential trade area. This stipulation can affect a firm’s ability to produce those goods if the use of foreign-sourced inputs is highly restricted. It also brings to the fore the core competitive advantages of certain countries, as those with the needed inputs for particular products may seek to protect their advantage by preventing others from sourcing those inputs externally. This issue can make RoO negotiations somewhat contentious. Stricter or more complicated RoO can have a trade-limiting effect and some studies assert that RoO design often raises costs above the level needed to deter trade deflection or transhipment. The complexity is further compounded since the AfCFTA builds on Africa’s existing RECs with Preferential Trade Areas (PTAs): the RoO negotiations will need to arrive at a set of common origin requirements from the highly differentiated and complicated rules already implemented within the PTAs.

As of November 2022, 88.3%5 of the RoO had been negotiated, but this is shy of the requisite 90% for the first stage of liberalisation. According to several reports, the more contentious tariff lines that may be stalling negotiations include, but may not be limited to, textiles and clothing, sugar, automotive goods and edible oils. Delays appear to be driven partly by clashes between national interests and AfCFTA aspirations, political changes in member states and sometimes even the personalities of negotiators. The listed items are closely linked to the industrial policies of many countries, given the high labour intensity of the items’ production, import substitution and export potential, value addition or capture by political settlements. Phase 1 negotiations have been ongoing since June 2015, and the delays in concluding them have served as the impetus for launching the GTI.

Beyond the negotiations, several other complementary initiatives have either been launched or are underway. These include:

- Oversight institutions such as the Council of Ministers, Committee of Senior Trade Officials and Committees of Trade Experts, which have been put in place to guide the implementation process

- A platform set up to monitor and address non-tariff barriers to trade within the continent6

- The Pan-African Payment and Settlement Scheme, which was launched in January 2022 to facilitate inter-currency payments under the AfCFTA

- The launch of the Dispute Settlement Mechanism for resolving trade disputes

- The AfroChampions initiative, which connects African private sector leaders and public officials in agencies such as the AU to support AfCFTA implementation

- The US$10 billion AfCFTA Adjustment Fund7 supported by the African Export-Import Bank, signed in February 2022

- The launch of the African Trade Observatory, which serves as a data repository for tracking changes in intra-African trade volumes to help monitor AfCFTA implementation and measure its impact.

- The launch of the AfCFTA Country Business Index, an ease-of-doing-business index focused on supporting AfCFTA implementation by identifying and monitoring progress on the elimination of trade barriers and bottlenecks affecting the private sector.

Also, after the 9th AfCFTA Council of Ministers Meeting in July 2022, a few other advancements were announced:

- The launch of the AfCFTA RoO Manual

- The launch of the AfCFTA e-Tariff Book

- The launch of the Initiative on Guided Trade

Other aspects of Phase 1 and Phase 2 of the negotiations are also advancing. Negotiations are ongoing for services trade, a part of Phase 1 negotiations. Progress is also being made on Phase 2 negotiation elements such as Women and Youth in Trade, Investment, Competition Policy, Digital Trade, and Intellectual Property Rights. There have also been announcements that the negotiations for the Protocol on Investment have been completed. Also at the continental level, the African Development Bank (AfDB) has recently granted US$11 million as institutional support for the AfCFTA Secretariat to help it meet its staffing needs and other requirements. Table 1 provides an overview of the phases, protocols and their content.

In summary, although there appears to be delays with the RoO negotiations, work is ongoing at the continental level to ensure readiness in the event of a full AfCFTA launch.

Table 1: AfCFTA Negotiation Phases

| Protocol | Content | |

|---|---|---|

| Phase 1 | Protocol on Trade in Goods |

|

| Protocol on Trade in Services |

|

|

| Phase 2 | Protocol on Investment |

|

| Protocol on Competition Policy | To be finalised | |

| Protocol on Intellectual Property | To be finalised | |

| Protocol on Digital Trade | To be finalised | |

| Protocol on Women and Youth in Trade | To be finalised | |

2.2 Regional

On the sub-regional level, the RECs have been playing their part in moving the AfCFTA implementation process forward. The Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS), the East African Community (EAC), the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and the Southern African Development Community (SADC) are all intended as AfCFTA building blocks. The inclusion of these RECs means that, where provisions at the REC-level allow for more liberalised trade between countries, those provisions will supersede the AfCFTA provisions; these RECs have pursued trade integration agendas to varying success levels, and their efforts will not be replaced by the AfCFTA. The growing integration within the RECs also means that, in some ways, the AfCFTA is about negotiating inter-REC trade. The AfCFTA negotiations are also tasked with consolidating the overlapping membership and trading regimes in the RECs of African countries. Table 2 shows the AU-recognised RECs and their progress on key integration measures.

For this reason, officials from the RECs have contributed to negotiations by aggregating tariff offers on behalf of their member states. This aggregation was the case for members of ECOWAS, ECCAS and the EAC, with collective tariff offers submitted by the RECs on behalf of their members. RECs also fill capacity gaps for their less-resourced countries that may not have the necessary trade negotiations under the AfCFTA. Critically, the RoO negotiations are interfacing with the preferential trade areas created by some RECs (or REC-PTAs) in an effort to harmonise rules. The REC-PTAs have been built on either REC free trade agreements or customs unions such as the Agadir, the Greater Arab Free Trade Area (GAFTA), the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), the EAC, ECOWAS or the SADC.

Table 2: Progress in Market Integration of African RECs

| REC | Free Trade Area | Customs Union | Common Market | Economic & Monetary Union | Supranational Union | Free Movement Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECOWAS | All 15 | |||||

| EAC | 3 out of 5 | |||||

| COMESA | Only Burundi | |||||

| ECCAS | 4 out of 11 | |||||

| SADC | 7 out of 15 | |||||

| AMU | 3 out of 5 | |||||

| IGAD | No protocol | |||||

| CENSAD | Unclear |

| YES | NO |

|---|

Note: Adapted from “Trade Creation and Trade Diversion in African RECs: Drawing Lessons for AfCFTA”, by Kassa, W. and Sawadago, P. N., 2021, World Bank Policy Research Series9 based on data from UNECA (2016)10

To complement national strategies, AfCFTA implementation strategies are also being prepared on the REC level. The RECs will also play a role in dispute settlement within the framework of the AfCFTA, and their operations - including successes and failures - will generally be a learning resource to guide the AfCFTA implementation.

2.3 National

The AfCFTA has enjoyed significant political will from its member countries, a will evidenced by the speed of ratifications and the accompanying efforts on the part of those countries to prepare for trade under the AfCFTA. Countries are developing or have developed AfCFTA implementation strategies and are actively building the awareness of their private sector players to enable them to take advantage of the AfCFTA. The implementation strategies aim to help countries identify the key value additions, opportunities and challenges to trade and measures needed to be better positioned for national, regional and global markets within the AfCFTA framework. The strategies also include elements such as finance, communication and monitoring and evaluation. Preparedness at the national level is a major criterion for including countries in the GTI.

2.3.1 The Guided (and Facilitated) Trade Initiative (GTI)

The GTI was launched on October 7, 2022 in Accra, Ghana. During his speech at the launch event, Wamkele Mene, Secretary General of the AfCFTA Secretariat, explained that the objective of the GTI was to kick-start commercially meaningful trading under the AfCFTA while Phase 1 negotiations are still ongoing. He also explained that he had submitted a proposal to the negotiating parties on the contentious tariff lines, including clothing and textiles and automobile.

2.3.1 Figure 2 AfCFTA Initiative on Guided Trade - Infographic

Note: Retrieved from the social media information of the AfCFTA Secretariat, 2022

The Secretariat is playing a significant trade facilitation role in the GTI and has signed a Memorandum of Understanding with McDan Aviation, a logistics company based in Accra Ghana that has pledged “two cargo planes and one vessel” for the transportation of goods under the initiative. The Secretariat has set up a Committee on the AfCFTA Guided Trade Initiative, which is working alongside other stakeholders, including the private sector. There are four Sub-Committees that demonstrate the extent of trade facilitation:

- Sub-Committee on Customs and Logistics, to focus on the AfCFTA customs cooperation and trading documents

- Sub-Committee on Non-Tariff Measures (NTMs), to examine and collect available NTMs applicable to goods covered under the AfCFTA GTI;

- Sub-Committee on Communications, charged with publicity, press engagement, planning and execution; and

- Sub-Committee on Services, to consider the activities related to trade in services under the GTI, priority being given to financial and transportation services for the first phase of the GTI.

(Source: Tralac, 2022)

The GTI currently includes eight countries and 96 products. Wamkele also expressed a possibility of “doubling or tripling” the list of products in 2023 as well as of expanding the list of participating countries. Part of the requirement for trading under the GTI is the identification of companies within a country that are ready to buy and sell the selected products. Ghana has identified 14 companies with 40 trades; Kenya has 27 companies with over 50 trades; Egypt has 7 companies with 20 trades; and Mauritius, Rwanda and Cameroon have, respectively, 25, 8, and 4 potential trades under the initiative. Trading has already occurred between Cameroon, Ghana, Kenya and Rwanda. The products are being traded under the Provisional Schedules of Tariff Concessions since the tariff offers have not been completed.

The GTI is an interim measure to help maintain political and public interest in the agreement. The legal basis for the GTI is said to be based on a previously adopted Council of Ministers directive that was intended to facilitate the commencement of trade on January 1, 2021. The national measures taken by participating countries to facilitate trade under the GTI are ad hoc, also because negotiations have not been finalised. There is therefore no doubt that the GTI is a temporary feature. There has been no clear communication of how long the GTI should last, but it appears it may last as long as it takes to finalise the critical Phase 1 negotiations. It is also instructive that the current phase of the GTI is referred to as the “pilot”, indicating plans for expansion, as expressed by Wamkele. Other countries have indicated their interest in the GTI and are in the process of joining the initiative.11

Reception to the GTI has been mixed. It is a welcome development to some trade scholars and practitioners, who view it as a necessary step to preventing a loss of interest in the AfCFTA. Its intention to gather the data needed to test and improve AfCFTA provisions is generally accepted as beneficial. There are, however, concerns that the GTI could take momentum away from the AfCFTA negotiations if it lasts too long. It has also been emphasised that the implementation of the AfCFTA should be state-driven even though the GTI requires more active involvement from the Secretariat. Significant effort is being invested by the Secretariat into ensuring Phase 1 negotiations are completed as quickly as possible so the AfCFTA can begin to be implemented, as stipulated by the provisions of the agreement.

2.3.2 State of Readiness of GTI countries

All eight countries selected for the GTI have signed and ratified the AfCFTA and have also submitted their tariff offers.12 The selected countries also had a special negotiation session to finalise preferential tariff offers ahead of the launch of the initiative. There were some key requirements for inclusion in the GTI:

- Submitting the provisional tariff offers for goods

- Selecting exporting companies and the products to be exported

- Creating an ad hoc committee to manage the initiative and coordinate with the committee formed by the AfCFTA Secretariat for this purpose.

- Publishing a legal text relating to the provisional tariff offers.

The eight countries’ levels of readiness beyond these indicators are discussed in the following paragraphs.

Cameroon

Cameroon has set up an inter-ministerial committee for monitoring and implementing the AfCFTA. The first meeting was held in November 2021. It has also submitted its tariff offers through ECCAS, although it is the only member state that will be participating in the pilot initiative. The country has also prepared its AfCFTA implementation strategy spanning 2020 - 2035 and linked it with its National Development Plan and its Industrialisation Master Plan. In 2019, about 4% of Cameroon’s exports went to African countries and about 21% of its imports originated from African countries.13 There is, therefore, room for increased intra-African trade through which the country is hoping to diversify its economic output. Cameroon is a member of ECCAS and the Central African Economic and Monetary Community (CEMAC) and, in some ways, is implementing the agreement with the support of both RECs. ECCAS is officially recognised by the AU but Cameroon is essentially operating within two FTAs in the two RECs.

Egypt

Egypt is one of the top five intra-Africa exporters and is well positioned to take advantage of the AfCFTA. In 2021, it was one of the top three origin countries for intra-African imports, as shown in Table 3, after South Africa and Nigeria. Although it is not clear whether Egypt has finalised its AfCFTA Implementation Strategy, it was supported by multilateral institutions such as UNECA, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and Afreximbank in creating a Product Transformation Policy Review to help the country benefit from the AfCFTA. AfCFTA implementation in Egypt is supported by its Ministry of Trade and Industry, and the country has been a keen supporter of the agreement. The AfCFTA can provide new markets for Egypt’s special economic processing zones, which brings an advantage for the country on the provision that the producers meet RoO requirements. The country is a member of COMESA, where it also enjoys preferential trade.

Table 3: Top 10 Intra-African Exporters in 2021

| S/N | Country | Export Value to Africa (USD billion) | Trade Balance (USD billion) | Share of Total Exports (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | South Africa | $26.19 billion | $17.01 billion | 21.2% |

| 2 | Nigeria | $6.07 billion | $4.69 billion | 12.8% |

| 3 | Egypt | $4.74 billion | $3.37 billion | 11.7% |

| 4 | Zimbabwe | $3.57 billion | $0.56 billion | 59.2% |

| 5 | Morocco | $2.89 billion | $0.67 billion | 7.9% |

| 6 | Kenya | $2.79 billion | $0.70 billion | 41.3% |

| 7 | Tanzania | $2.51 billion | $1.26 billion | 39.3% |

| 8 | Zambia | $2.16 billion | -$1.02 billion | 19.3% |

| 9 | Senegal | $1.97 billion | $0.77 billion | 43.9% |

| 10 | Eswatini | $1.92 billion | $0.32 billion | 92.9% |

Note. Data compiled by author from ITC Trade Map Database, 2022

Table 2 shows that Africa’s top three exporters in 2021 enjoyed significant trade surpluses. Eswatini, Zimbabwe, Senegal, Kenya and Tanzania had the highest share of their total exports going to African markets. Of the ten, Zambia was the only country that imported more than it exported to other African countries.

Ghana

As the host of the AfCFTA Secretariat, Ghana is also in an advantageous position for the AfCFTA implementation. It launched its National AfCFTA Policy Framework and Action Plan in August 2022, a document that will serve as its implementation strategy. In November 2021, the government also published guidelines for local authorities implementing the AfCFTA. It has an advanced support system around AfCFTA implementation, including an Inter-Ministerial Committee and a National AfCFTA Steering Committee, as well as several technical working groups consisting of private and public sector leaders. The Customs Division of Ghana’s Revenue Authority was assigned designated competent authority (DCA) status and has been implementing reforms to support trade facilitation. These reforms include the single customs window that would allow Ghanaian traders to easily navigate between the different agencies to get the necessary trade licences and permits. Ghana is already participating in the GTI and received a shipment of Exide batteries from Kenya on September 23, 2022.

Kenya

Kenya launched its AfCFTA Implementation Strategy in August 2022, with the plan spanning from 2022 - 2027. It is a member of two RECs, EAC and COMESA, where it is already navigating trade integration and related issues. It has initiated an ad hoc committee to coordinate GTI processes and sent the first shipment under the initiative to Ghana on September 23, 2022. Like Ghana, the Customs Division of its Revenue Authority has been assigned DCA status. It is among the top five intra-African exporters and is well positioned to benefit from the AfCFTA.

Table 4: Current trade between GTI countries 2021 (US$ millions)

| Importing Country Exporting Country | Cameroon | Egypt | Ghana | Kenya | Mauritius | Rwanda | Tanzania | Tunisia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cameroon | 1.27 | 0.38* | 0.65 | 3.05 | 66.54* | 0.006 | 1.68 | |

| Egypt | 60.50 | 128.59 | 339.41 | 25.34 | 37.42 | 41.92 | 231.43 | |

| Ghana | 2.67* | 15.93 | 4.45 | 0.02 | 0.07* | 2.84 | 10.9 | |

| Kenya | 2.41 | 193.14 | 10.30 | 11.29 | 278.37 | 409.76 | 9.77 | |

| Mauritius | 0.67 | 0.17 | 0.71 | 50.9 | 2.1 | 2.45 | 0.005 | |

| Rwanda | 0.001* | 6.48* | 0.65* | 12.1* | 0.11* | 5.04* | 0.12* | |

| Tanzania | 0.12 | 3.52 | 3.05 | 397.23 | 0.18 | 277.80 | 0.19 | |

| Tunisia | 34.46 | 66.93 | 22.83 | 20.83 | 6.28 | 0.21 | 0.72 |

Source: Trade Map (accessed November 2022)

*Figures are from 2019

As shown in Table 4, on average, there is low bilateral trade between the GTI countries, but higher trade volumes are seen between those that are members of the same RECs. Kenya and Tanzania have one of the strongest trading relationships among GTI countries.

Mauritius

Mauritius has prepared and validated its National AfCFTA Implementation Strategy and is working to remove the barriers facing its exporters. It is implementing a series of projects such as the Africa Warehousing Scheme and the Freight Rebate Scheme14 targeted at increasing the competitiveness of its exporters under the AfCFTA. The country is also co-opting its TradeNet Portal to enable its exporters to easily apply for the necessary certifications, such as the RoO certificate, and trade under the AfCFTA. It is a member state of COMESA and the SADC. Mauritius has a growing garment production sector, which is informing the country’s position in the AfCFTA negotiations. It is also the only African country to sign an FTA with China, which may be driving its negotiation for more liberal RoO for its target sectors. The country has an Africa Strategy, which it is seeking to align with its AfCFTA Strategy.

Rwanda

Rwanda announced that it was ready for trade under the AfCFTA in January 2021. In June 2022, it validated its National AfCFTA Implementation Strategy, which is expected to help identify the priority goods and services for trade under the agreement. Rwandan exporters can apply for their Certificate of Origin via an online platform that promises greatly reduced waiting times. The Rwandan authorities are also trying to address other non-tariff barriers and have recently issued a special freight tariff for its exporter under the AfCFTA. Its AfCFTA agenda is driven by the Minister for Trade while its revenue authority serves as the DCA. The country is generally supportive of regional integration efforts and has also signed the Protocol for Free Movement of Persons.

Tanzania

Tanzania is a member of the EAC alongside two other countries in the GTI, Kenya and Rwanda. Tanzanian President, Samia Suluhu, is an AfCFTA champion and is also drawing attention to the provisions that relate to women in trade, with the country hosting the September 2022 conference on women and the AfCFTA. It is not clear whether Tanzania has finalised its AfCFTA Implementation Strategy.

Tunisia

Tunisia has prepared and validated its AfCFTA Implementation Strategy. The country is working to simplify export and import formalities to make it easier for its traders to participate in the AfCFTA. It is also in the COMESA sub-region but anticipates trading with countries not within the region. AfCFTA implementation in Tunisia is managed by the Ministry of Trade and Export Development. Prior to now, Tunisia’s trade was primarily Eurocentric, which creates significant room for a growth in intra-African trade. According to the 2022 African Regional Integration Index report, as shown in Table 5, Tunisia had the lowest trade integration score. It therefore has some ground to cover as it seeks to leverage the AfCFTA.

Table 5: 2020 Trade Integration Scores for selected countries

(Higher scores indicate better trade integration)

| S/N | Country | Score | Methodology - Trade Integration Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ghana | 0.454 |

The trade integration score is an aggregate of the components below:

|

| 2 | Rwanda | 0.435 | |

| 3 | Kenya | 0.428 | |

| 4 | Egypt | 0.414 | |

| 5 | Mauritius | 0.318 | |

| 6 | Nigeria | 0.325 | |

| 7 | Tanzania | 0.323 | |

| 8 | Cameroon | 0.255 | |

| 9 | Tunisia | 0.189 |

Note. Data compiled by author from the Africa Regional Integration Index, 202115

Nigeria

Although Nigeria is not currently participating in the GTI, it is one of the countries that expressed an interest in starting trade under the AfCFTA and continues to put pressure on the Secretariat to be included. It has completed its implementation strategy and has assigned its Customs Service as the DCA. In Nigeria, AfCFTA monitoring and implementation is performed by the National Action Committee, an inter-agency committee with a Secretariat that brings together experts from across the public sector. Due to its large population, one of the country’s focus areas under the AfCFTA is services export.

For trade in goods, the country has been actively sensitising and training private sector actors to better leverage the AfCFTA. However, its trade conservatism has been argued as a cause for concern, as has the absence of a single customs window. The country closed its borders with its neighbours for two years in August 2019, supposedly to combat the smuggling of goods. Smuggling and dumping remain high on list of the country’s concerns, and it expressed its intention to secure its markets against these illegal actions under the AfCFTA. There are concerns that perceived abuse of the RoO provisions during AfCFTA implementation could cause Nigeria to withdraw from the agreement. One study attempting to use social media to measure public awareness and sentiment around the AfCFTA found higher negative sentiments from West African users, primarily driven by Nigerians.

2.3.3 Cross-cutting national issues

The domestication of the AfCFTA through national parliamentary processes is a step that no country has been able to complete as it requires the initiation of legislative processes that are usually slow. However, the leadership of the AfCFTA Secretariat continues to urge countries to do so quickly. There is, nonetheless, no strong sense of urgency, given that the instruments of ratification are arguably sufficiently binding.

All countries under review here share a keen interest in export-led industrialisation, and this interest has driven their awareness campaigns targeted at private sector leaders. Countries have held a series of sensitization workshops online and offline to inform small and large businesses about the opportunities the AfCFTA presents. Workshops have also been held to demonstrate the key instruments and tools needed to trade under the AfCFTA including the explanation of technical concepts such as the RoO.

Across all countries, there are varying levels of awareness of non-trade related public sector officials. However, there appears to be a level of detachment among officials that are not directly involved in the AfCFTA processes and do not understand the ways their roles intersect with the agenda.

3. Policy Issues

Through the AU and other RECs, the African continent has launched and embarked on several initiatives aimed at increasing integration, with mixed results. Monetary, trade, banking and other commercial systems are still largely disconnected from each other, although some progress has been made on the REC level in a few regions. It is important to understand the challenges to trade integration in Africa as may be applied to the AfCFTA.

3.1 Implementation Challenges

AfCFTA implementation faces several issues, and more will emerge during the GTI period. A number of these issues are discussed below.

Sustainability of AfCFTA implementation support

AfCFTA implementation requires immense financial resources at the continental, sub-regional and national levels: resources to hire skilled labour to manage the implementation process, to convene forums and workshops for negotiations and to conduct different activities related to trade facilitation. Low average incomes and constrained fiscal space in African countries mean that these resources are often provided by external actors. Some major funders of the AfCFTA implementation process include the United Nations, the EU, the German Development Agency (GIZ), the United Kingdom’s Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Agency, the OECD and a host of other governmental and non-governmental organisations.

That issue is tied to the question of the precarity of the deployment of a significant portion of the expertise that is accompanying the agreement’s implementation. Almost all national AfCFTA implementation strategies have been produced using external support, and the activities of some national coordinating entities are also largely funded by donors. In the event of changing priorities of these donors, this support may be at risk. A related issue is the implication of foreign expertise supporting the negotiation of instruments such as the Investment Protocol, and whether this expertise could introduce non-African agendas into those policy documents. On the other hand, the Afreximbank and the AfDB are regional institutions that are also financially supporting the AfCFTA implementation process.

Inequalities, political will and competing interests

Although the AfCFTA has enjoyed significant political will from member states, the stalling of negotiations highlights the stark realities of the clashes occurring between national interests and the wider pan-African agenda. The AfCFTA is argued to have the widest income disparities among its member states. Countries such as Egypt, Nigeria and South Africa account for more than half of the continent’s GDP. Beyond incomes, however, is the question of productive capacity and industrialisation levels. Popular measures of industrialisation include Manufacturing Value Added (MVA) per capita or as a percentage of GDP. From that perspective, countries that are better positioned to dominate trade under the AfCFTA among the GTI countries include Mauritius, South Africa, Tunisia and Egypt, as shown in Table 6. While this domination is not negative in itself, it ties back to the notion of the “winners” and “losers” created by free trade.

Table 6: Measures of productive capacity and industrialisation

| S/N | Country | Productive Capacity (2018) | MVA per capita - 2021 (US$)16 | MVA - 2021 (% of GDP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mauritius | 37.39 | 1036 | 11.1 |

| 2 | South Africa | 34.05 | 596 | 11.3 |

| 3 | Tunisia | 33.24 | 533 | 14.6 |

| 4 | Egypt | 29.39 | 588 | 14.9 |

| 5 | Ghana | 26.90 | 239 | 11.5 |

| 6 | Kenya | 25.73 | 145 | 8.9 |

| 7 | Rwanda | 25.42 | 71 | 7.9 |

| 8 | Tanzania | 24.23 | 87 17 | 8 |

| 9 | Cameroon | 23.60 | 213 | 15.7 |

| 10 | Nigeria | 21.65 | 213 | 8.7 |

Note. Data compiled by author from the following databases: UNCTADStat Productive Capacities Index, UNIDO Statistics Data Portal, and World Bank.

The issue that arises here is that “smaller” countries are concerned about being dominated by “bigger” countries. Countries like Nigeria, with large populations and low productive capacities, are also aware of the interest in their consumer markets and are seeking to somewhat restrict access. Other countries that are commodity exporters, such as Zambia, have shared their caution about the implications of full liberalisation for their economy. Kenyan manufacturers have expressed their concern over the comparative competitiveness of some of their products, and there are already issues surrounding the growing dominance of Egyptian imports in East African markets.18 This dominance is due to the higher competitiveness of some products from Egypt, as a result of the country’s growing special economic zones. The Kenyan Revenue Authority is also concerned with tariff losses under the AfCFTA, following a study that projected that Kenya would experience the highest tariff revenue loss within the EAC region at US$14.2 million, as shown in Table 7. Several countries are wary of current and future tariff losses, despite the AfCFTA adjustment arrangements being made by the Afreximbank. However, according to World Bank calculations, tariff revenues will decline by less than 1.5% for 49 out of the 54 AfCFTA member countries. As Table 8 below shows, adjustment costs are not only fiduciary.

Table 7: Estimated tariff revenue losses in EAC under the AfCFTA

| S/N | Country | Tariff revenue effect of AfCFTA (US$ million) | Tariff loss as share of total tariffs |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kenya | -14.19 | 4% |

| 2 | Uganda | -13.49 | 7.6% |

| 3 | Tanzania | -5.34 | 3.7% |

| 4 | Burundi | -4.38 | 30% |

| 5 | Rwanda | -3.94 | 5.5% |

Note. Reprinted from “African Continental Free Trade Area: The potential revenue, trade and welfare effects for the East African Community”, by Shinyekwa, I., Bulime, E., and Nattabi, A. (2020), Economic Policy Research Centre, Research Series No 153. Copyright 2020 by the Economic Policy Research Centre.19

Table 8: Components of adjustment costs under free trade areas

| Components of adjustment costs under free trade areas | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Social adjustment costs | Private adjustment costs | Labour |

|

| Capital |

|

||

| Public sector adjustment costs |

|

||

Note. Reprinted from “Trade adjustment costs and assistance: The labor market dynamics”, by Francois, J., Jansen, M., and Peters, R., 2011, In Trade and Employment: From Myths to Facts, eds. Jansen, M., Peters, R. and Salazar-Xirinachs, J.M. Copyright 2011 by the International Labour Organisation and European Commission, Geneva.20

There is some speculation about the countries holding up negotiations. Among others, Mauritius, Nigeria and South Africa are considered to be taking harder lines in the negotiations. Nigeria’s position appears to be consistent with its general conservatism on issues of trade openness. Its main export to Africa is crude oil, 76% of its exports to Africa in 2021. The country’s second largest export category to Africa is ships, boats and floating structures, 22% of total exports in 2021. Other products such as cement and fertiliser have much lower export volumes but are part of the country’s industrial policies. Even beyond these areas, with its approach of import substitution industrialisation, Nigeria continues to try to protect industries that are somewhat inexistent or largely unformed. Its large population and low productive capacity drive it to restrict access to its consumer market. Plastics and fertilisers were two of Nigeria’s largest imports from Africa in 2021.

On the other hand, South Africa, as a more industrialised economy on the continent, is taking positions that seek to protect the share it currently holds of intra-African trade. Around 65% of intra-African trade takes place within the SADC, and South Africa dominates trade within the sub-region. Mauritius is reportedly seeking a more liberal RoO for textiles and apparel, which may let it leverage the FTA between the country and China to access cheaper inputs. The clash between the desire for single transformation or double transformation of textiles and apparel for these products to qualify for preferential trade under the AfCFTA is a significant challenge to the RoO negotiations.

In essence, as often happens in trade negotiations, the AfCFTA negotiations are witnessing a clash between continental aspirations and national interests. Although national interests are often varied and may sometimes overrepresent the needs of the political and industrial elite, they are not to be disregarded; on average they represent the needs of the voting public. Research also supports the notion that, when free trade is not properly managed, it can increase regional inequalities and exacerbate uneven development. Import exposure can also lead to heightened protectionism and xenophobia. Misaligned national and continental aspirations can affect public support for integration projects but also governments’ commitments to implementation. There are therefore multi-level games taking place during the AfCFTA negotiations, with an array of interests competing for primacy. These interests can sometimes manifest as fluctuating political will to move the agreement forward.

Growing complexity and implementation capacity

As AfCFTA implementation advances, the processes are becoming increasingly complex with several different actors and stakeholders. The launch of trade will criss-cross RECs, and this will be happening within the context of some African countries being members of multiple RECs. Complexity, without sufficient guidance for its resolution, can act as a non-tariff barrier to trade and is often instrumentalised as a non-tariff measure. It can also increase the difficulty faced by national trade officials in implementing the agreement, resulting in competency-driven trade barriers. These barriers will also affect investment. A report on the perception of private sector players in the EAC showed that, although there was interest in driving cross-border investment, the disparate regulatory practices and frameworks were a disincentive. On the other hand, the AfCFTA also seeks to reduce complexity by bringing together the different RECs and their PTAs.

Trade facilitation, trade disputes and infrastructure deficit

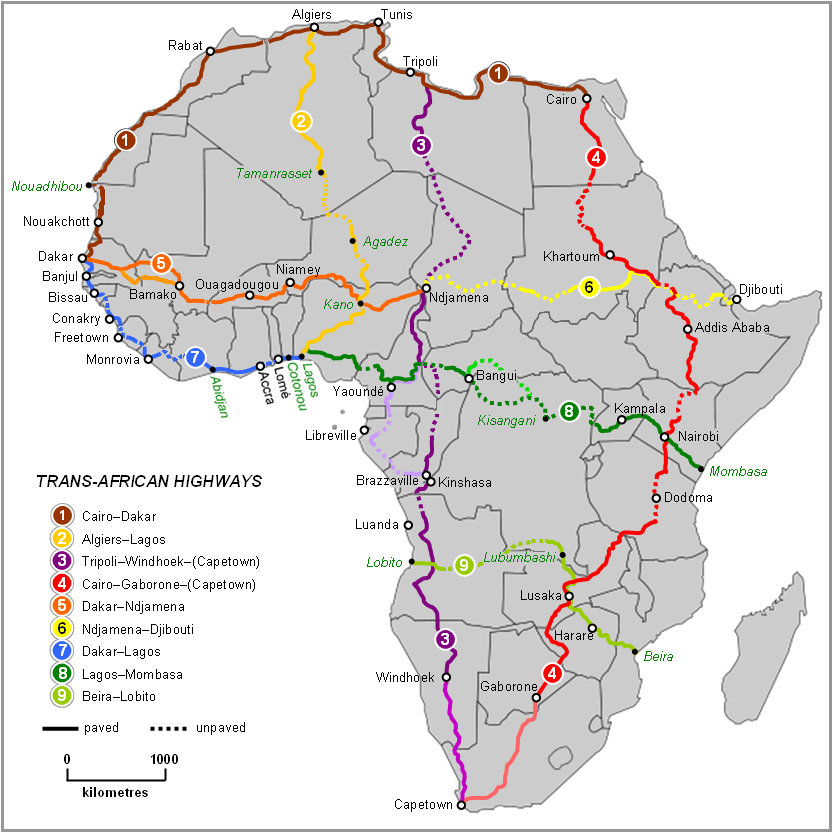

Key to AfCFTA’s success will be the competitiveness of intra-African imports and their ability to enable a growth in demand and a preference for them over goods from outside the FTA. However, a significant element of the price of an imported good is the transaction cost of moving it from one country to another. These costs can include transportation, but also non-tariff related monetary and non-monetary costs imposed intentionally at borders or ones that are simply a result of inefficiencies. The inadequate road networks and high cost of air and sea transport are challenges that will need significant investment to overcome. The AU and its partners are already seeking to address these challenges with plans to review the Trans-African Highway Network for implementation gaps (Figure 3) and a pilot of the Single African Air Transport Market. Trade corridors are receiving some financing support from the AfCFTA countries, and regional entities will also need to invest in digitalising their customs processes to reduce waiting times and make the processes less vulnerable to corruption. Trade facilitation will be key to resolving these issues, but the political and economic resources required to do so effectively are immense.

Figure 3: Trans-African Highway Network

Note: Reprinted from “Review of the Implementation Status of the Trans-African Highways and Missing Links”, by the African Development Bank, 2003

The approach to and speed of addressing the first few sets of issues raised by non-tariff barrier monitoring and the dispute settlement mechanisms set up by the AfCFTA Secretariat will have a strong signalling effect for AfCFTA member countries. Linked to this approach is the creation of suitable platforms and marketplaces connecting firms across the continent, but also connecting firms to potential consumers.

External actors and factors

External actors that may affect AfCFTA implementation include countries and regions that have established or are seeking to establish FTAs with AfCFTA member countries. These agreements include the established or ongoing bilateral trade agreements between countries such as Kenya and Ghana with Western countries such as the United Kingdom and the United States. They also include the FTA between China and Mauritius and how both parties may seek to influence the AfCFTA in favour of that FTA. The Economic Partnership Agreements (EPA) between the EU and some African countries is another example of an FTA. The challenges these FTAs may pose are already illustrated by some of the developments on the REC level. The United Kingdom recently rejected the application of the increase in import tax charges within the EAC, suggesting that it goes against the provisions of the EPA. Since a significant portion of African trade is with partners outside Africa, it will be important to monitor these issues closely.

Related to these issues is the need to attract more Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) into the continent to boost manufacturing capacity to meet African demand for goods under the AfCFTA. However, although FDI is generally considered to be positive, it can also have harmful effects on economies. If not managed carefully, FDI can result in a large part of the income gains from intra-African trade leaving the continent through capital outflows. Other external factors include changes in the global political economy that can cause countries to withdraw from regional arrangements and look more inwards.

4. Policy Recommendations

To produce lessons for the AfCFTA, a 2021 World Bank report analysed the trade creation or trade diversion effects of the eight RECs recognised by the AU. It found that the SADC and the EAC were the most successful RECs, and connecting features included significant investment in trade facilitation, closer alignment between national and regional goals and investment in improving regional infrastructure. This section will put forward pragmatic recommendations for the AfCFTA, while acknowledging that various actors are already paying attention to some of these issues.

Leadership and coordination

The current challenges in the RoO negotiations may require a stronger show of collaborative leadership from leading economies that are part of the agreement. It may be time for a political solution to the stalled negotiations since the technical negotiations are struggling. Finding common ground and unblocking the implementation process should be the objective of all parties, especially considering that the AfCFTA agreement makes a provision for revising submissions every five years.

In response to the AfCFTA, there are ongoing efforts towards coordinating production policies to build complementary production structures on the continent. A trade and industrial development advisory council of the AfCFTA was inaugurated in March 2022, with key appointments from within African governments and non-governmental organisations. This council has been tasked with establishing the link between the AfCFTA and industrial growth in African countries. Numerous attempts to harmonise national industrial policies have taken place at the REC level, but they have faced significant challenges. Efforts therefore need to be ramped up and require political leadership from large economies. Coordinating production or industrial policies will also require increased coordination of investment promotion efforts. To limit potential clashes in the future, regional integration aspirations also need to be reconciled with national strategies. To improve negotiation outcomes, collaboration must improve between the technical leaders of the AfCFTA Secretariat and the political leaders in the AU.

Institutionalise AfCFTA Support and Finance

The institutionalisation of support to and for the AfCFTA will need to happen on the continental, regional and national levels to reduce the agreement’s vulnerability to political changes or individual whims. African multilaterals, such as the AfDB and Afreximbank, have shown unwavering support for AfCFTA implementation, and to forestall difficulties arising from leadership changes, it is important that this support is institutionalised. The growing efforts to coordinate industrial policies and investment may also need continental mechanisms to oversee them. Member states also need to be further urged to begin and complete domestication processes for the AfCFTA, and RECs need to properly embed AfCFTA-related processes into their systems. Ad-hoc arrangements are more likely to collapse in the event of internal or external changes. Support from external actors needs to be driven by the priorities set by the Secretariat and national governments in the form of research, capacity building and trade finance. This support should not be entirely subject to donor project-funding cycles but should include more sustainable technical partnerships for peer learning and exchanges. To ensure continuity and reduce disruption, the support from the World Trade Organisation should be similarly embedded.

Pragmatism and Messaging

The implications of the imbalances among AfCFTA state parties must be confronted directly with an honest assessment of the implementation risks across countries. Directly addressing these issues is the only way identified challenges can be dealt with in a process that is sometimes referred to as development bargains. Addressing the challenge of production subsidies and the need for fair competition may require innovative thinking beyond outright bans.21 The AfCFTA is not only about exporting to Africa but also about importing from Africa. Estimations of the gains from trade are linked not only to export-driven growth but also to consumer surplus through cheaper imports. It is important that the AfCFTA Secretariat and other stakeholders begin to manage the messaging around this topic as many countries are concentrating more on positioning themselves for exports while importing raw materials from other African countries as shown in the interview excerpt below.

“It is our hope that the business community has understood that the continental free trade agreement is ready (for them) to start exporting made in Rwanda products to African countries. It is also an opportunity to secure and source raw materials and inputs from all the African state countries which can support local manufacturing here in Rwanda.’’

Rwanda Minister of Trade and Industry, Soraya Hakuzitaremye

Source: CNBC, 2021

Trade is a give and take relationship, and for every million dollars’ worth of goods exported on the continent, there needs to be receiving markets for these goods. Large economies, such as that in Nigeria, need to be more welcoming of African imports and understand that there can be a net gain for their citizens. The discourse around regional value chains has to be amplified as one way to begin to shift the perceptions of African policymakers on intra-African trade. Careful management of the messaging can mobilise more public support for the AfCFTA and help avert future resistance to import exposure, an inevitable reality in the context of an FTA. Mass and cultural media tools such as social media and films should be considered for an even wider dissemination of information on the AfCFTA and its objectives. The messaging around intra-African investment also needs to be ramped up to better prime African private sector actors for expansion into African markets beyond their home countries.

Objectives should be kept front and centre

Restrictive RoO that will limit trade participation may not be the best approach, and there should be an opportunity to revise these terms every five years (or within a shorter provisional timeframe). Negotiations should not be viewed as a static end goal but as an ongoing process that will continue during the decade plus of tariff liberalisation. There is a need to prioritise milestones that may yield more immediate returns as this prioritisation will be key to canvassing political support for the process. AfCFTA implementation will be highly political and therefore requires the maximum amount of political support for success. Also, the focus on helping SMEs trade under the AfCFTA is laudable and helps with economic inclusion, but it is important that stakeholders do not lose sight of large firms that are the main drivers of cross-border trade. Trade facilitation efforts should support large firms, and SMEs that are not well-positioned for cross-border trade can also be supported in their attempts to embed themselves in the value chains of those firms. That way, the gains of trade will not accrue in a single direction. Linked to this support is the need to remain focused on the more immediate objective of initiating full AfCFTA implementation. This focus will put initiatives such as the GTI into perspective and reinforce it as an interim solution that should not last too long.

It is also important that integration dynamics drive the response of African countries to external bilateral arrangements, and not the other way around. Common positions that are agreed on should be maintained even in the face of pressure from external partners such as China, the EU, the United Kingdom and the United States.

Increase and sustain private sector engagement

Given that governments do not trade with each other,22 trade under the AfCFTA will largely be driven by the private sector. In some countries, the African private sector has been playing an active part in the AfCFTA process. This role is in line with policy best practices: the relationship between the government and the private sector should not only be in one direction with the private sector waiting for the provision of support and an enabling environment by government actors. A high value resource that private sectors have access to, and one that is often overlooked, is information. Bureaucrats may have inadequate information on the day-to-day realities of navigating trade infrastructure. Private sector actors can seek to share their information in a timely manner, to enable both sides to move closer to meeting the shared objectives. The private sector can also play a role in facilitating trade through investment in logistics and other trade infrastructures.

5. Conclusion

Regional integration takes time. Africa has embarked on an ambitious project that seeks to correct dynamics imposed by external factors such as colonialism and structural adjustment policies. To ensure the eventual success of the AfCFTA, it is important that all stakeholders view the processes with the level of pragmatism required to properly identify and address challenges that may be standing in its way. Pragmatism also requires that African countries confront the challenges with the uneven distribution of the gains from the AfCFTA and fast-track accompanying protocols23 that will allow labour mobility across the continent. The GTI, although not without its flaws, provides a testing ground for the AfCFTA. It is, however, important that all stakeholders involved are diligent in the collection of the data that will be generated from the initiative.

Appendix 1: Tariff liberalisation schedule for LDCs, non-LDCs and G6

| LDCs | Non-LDCs | G6 countries | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full liberalisation | 90% of tariff lines 10-year phase down |

90% of tariff lines 5-year phase down |

90% of tariff lines 15-year phase down |

| Sensitive products | 7% of tariff lines 13-year phase down (current tariffs can be maintained during first 5 years – phase down starting in year 6) |

7% of tariff lines 10-year phase down (current tariffs can be maintained during first 5 years – phase down starting in year 6) |

Not yet determined |

| Excluded products | 3% of tariff lines | 3% of tariff lines | Not yet determined |

Note. Reprinted from “The African Continental Free Trade Area Agreement – what is expected of LDCs in terms of trade libéralisation?”, by Trudi Hartzenberg (2021), Copyright 2021 United Nations

Appendix 2: AfCFTA Implementation Status of Selected Countries

| Economic Size (GDP US$ - 2021) | Signed and Ratified | National Entity | Implementation Strategy | DCA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cameroon | 45,238.6 billion | YES | YES - Specialised Interministerial Committee for AfCFTA Monitoring and Implementation |

YES National Strategy for the Implementation of the African Continental Free Trade Area in Cameroon 2020 - 2035 |

YES Cameroon Autonomous Port Authority |

| Egypt | 404.1 billion | YES | YES | YES Product Transformation Policy Review |

YES |

| Ghana | 77.6 billion | YES | YES Inter-Ministerial Committee, a National AfCFTA Steering Committee as well as several technical working groups |

YES National AfCFTA Policy Framework and Action Plan |

YES Customs Division, Ghana Revenue Authority |

| Kenya | 110.3 billion | YES | YES | YES National African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) Implementation Strategy 2022-2027 |

YES Customs Division, Kenya Revenue Authority |

| Mauritius | 11.2 billion | YES | YES | YES The Mauritian Strategy to Leverage the Opportunities of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) |

YES Customs Department, Mauritius Revenue Authority |

| Rwanda | 11.1 billion | YES | YES Ministry of Trade and Industry |

YES National AfCFTA Implementation Strategy |

YES Rwanda Revenue Authority |

| Tanzania | 67.8 billion | YES | YES | Ongoing | YES Tanzania Revenue Authority |

| Tunisia | 46.8 billion | YES | YES Tunisian Ministry of Trade and Export Development |

YES National AfCFTA Implementation Strategy |

YES Chamber of Commerce |

| Nigeria | 440.8 billion | YES | YES - Specialised National Action Committee for the Implementation of the AfCFTA |

YES Nigeria’s AfCFTA Strategy and Implementation Plan |

YES Nigerian Customs Service |

Note. Compiled by author from various sources

- LDCs are Angola, Benin, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, Democratic Republic of Congo, Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gambia, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Lesotho, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Mozambique, Niger, Rwanda, Sao Tome and Principe, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Togo, Uganda, United Republic of Tanzania, Zambia.

- The G6 countries are Ethiopia, Madagascar, Malawi, Sudan, Zambia, Zimbabwe

- Table in Appendix 1

- Eritrea is the only African country that has not signed the agreement

- Information shared by AfCFTA official

- Available at https://tradebarriers.africa/

- The Adjustment Fund is a financing instrument that seeks to cushion the loss in tariffs under the AfCFTA for less developed economies and support trade facilitation on the continent

- Five priority sectors include business services; communications; finance; tourism and transport

- Kassa, W. and Sawadogo, P. N. (2021). Trade Creation and Trade Diversion in African RECs: Drawing Lessons for AfCFTA. (World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 9761). World Bank, Washington, DC. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/36226.

- United Nations Economic Commission for Africa. (2016). Assessing regional integration in Africa vii: Innovation, competitiveness and regional integration. Addis Ababa: UNECA.

- Deduced from interview with a trade official

- Appendix 2 provides more information on this

- Around 70% of Cameroon’s African imports were from Nigeria

- These are trade facilitation measures targeted at improving transport and logistics for Mauritian traders

- Available at www.integrate-africa.org

- Values are constant 2015 United States dollars

- Author’s estimation from World Bank data

- Interview with Kenyan customs official

- Shinyekwa, I., Bulime, E., and Nattabi, A. (2020). African Continental Free Trade Area: The potential revenue, trade and welfare effects for the East African Community. Economic Policy Research Centre, Research Series No 153.

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/346677395_African_Continental_Free_Trade_Area_The_potential_revenue_trade_and_welfare_effects_for_the_East_African_Community

- Francois, J., Jansen, M., and Peters, R. (2011). Trade adjustment costs and assistance: The labor market dynamics. Trade and Employment: From Myths to Facts, eds. Jansen, M., Peters, R. and Salazar-Xirinachs, J.M., ILO and European Commission, Geneva.

- Such as the proposal to ban goods from Special Economic Zones

- One exception will be meeting the demand of goods from government procurement in one country through the supply of goods through state owned enterprises in another country - government to government trade.

- For example, the African Union’s Protocol for the Free Movement of Persons.

About the Author

Teniola T. Tayo is a Policy Advisor with a focus on trade, security and development issues in Nigeria and Africa. Her research interests cover trade policy, industrial policy, investment promotion, inequality, and stabilisation. She has previously worked as a senior legislative aide with the Nigerian Senate and a consultant with the Office of the Vice President.